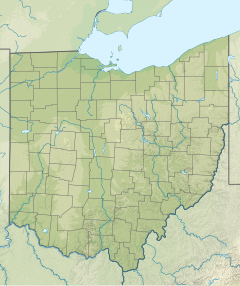

Euclid Creek is a 43-mile (69 km) long stream located in Cuyahoga and Lake counties in the state of Ohio in the United States. The 11.5-mile (18.5 km) long main branch runs from the Euclid Creek Reservation of the Cleveland Metroparks to Lake Erie. The west (also known as south) branch is usually considered part of the main branch, and extends another 16 miles (26 km) to the creek's headwaters in Beachwood, Ohio. The east branch runs for 19 miles (31 km) and has headwaters in Willoughby Hills, Ohio.

| Euclid Creek | |

|---|---|

Euclid Creek near Euclid, Ohio | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Cuyahoga County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Near 26611 Fairmount Blvd., Beachwood, Ohio |

| • coordinates | 41°29′14.1894″N 81°29′25.4322″W / 41.487274833°N 81.490397833°W[1] |

| • elevation | 1,083 ft (330 m) |

| Mouth | Lake Erie |

• location | Cuyahoga County, Ohio |

• coordinates | 41°35′13.1778″N 81°33′55.443″W / 41.586993833°N 81.56540083°W[1] |

• elevation | 581 ft (177 m)[1] |

| Length | 46.5 mi (74.8 km) |

| Basin size | 23 sq mi (60 km2) |

The stream has exposed geologic formations which proved of importance to science, and these formations proved economically important in the Cleveland, Ohio, area in the early and mid 1800s. Five major in-channel obstructions impair the stream, which runs through a heavily urbanized area east of Cleveland. Portions of the creek are culvertized and channelized, and the stream has been heavily polluted in the past. Although the level of pollution has lessened in the last 30 years, the fishery remains significantly impaired. The development of settlements along Euclid Creek is an important part of the history of the development of Cleveland's east side, and some of the major retail developments in the watershed in the past 60 years[as of?] have impaired the stream.

Location and flows

editEuclid Creek is a stream which originates in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. It flows through Cuyahoga County and a small portion of Lake County before emptying into Lake Erie.[2] Euclid Creek is one of about 100 streams that drain directly into the lake.[3] Doan Brook and Euclid Creek are the largest of the minor tributaries of Lake Erie.[4]

The stream consists of a main branch, an east branch, and several named and unnamed tributaries. Many sources say that the main branch extends from the mouth of the stream about 11.5 miles (18.5 km) upstream, where an east branch and west (or south) branch meet.[5] The watershed drained by this segment of the creek is about 3 square miles (7.8 km2) in size.[2] However, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA) treats the main branch and west branch as a single main branch, which is the description used in this article.[6] Upstream from the confluence of the two streams, the main/west branch extends for another 16 miles (26 km) and drains a watershed of about 8.5 square miles (22 km2). The east branch is 19 miles (31 km) long and drains a watershed of about 12.5 square miles (32 km2).[6] The main branch and east branch (exclusive of tributaries) are a combined 46.5 miles (74.8 km) long, with a combined watershed approximately 24 square miles (62 km2) in size.[2] More than 100 streams make up the headwaters of Euclid Creek.[7]

The Euclid Creek watershed is one of the most highly urbanized areas of the Lake Erie coastline in Ohio.[8] The watershed contains 11 cities, 10 of which are in Cuyahoga County.[3][9] About 68,000 people live in the watershed.[2]

Euclid Creek has an average grade of 55 feet per mile (10.4 m/km), or 1.04 percent, a very high gradient for a stream.[2] The gradient varies from place to place along the creek. Near its headwaters, the grade is 37 feet per mile (7.0 m/km), while within the Euclid Reservation Metropark the grade increases to 58 feet per mile (11.0 m/km). In the lacustuary near its mouth,[a] the grade is just 0.1 feet per mile (1.9 cm/km).[6]

Underlying geology

editEuclid Creek flows over bedrock more than 360 million years old.[6] This includes the 365 million year old[12] Chagrin Shale,[13] the 360 million year old[14] Cleveland Shale,[13] the 358.9 million year old[15] Bedford Formation,[13] the 360 million year old[16] Berea Sandstone,[b] and the 354.8 to 351.4 million year old Orangeville Shale of the Cuyahoga Formation.[13][c] The Berea Sandstone is highly resistant to erosion, and the highest waterfalls on Euclid Creek occur where the stream has cut down to the Berea.[19]

Topographically, the underlying geology creates three distinct areas: The Allegheny Plateau, the Portage Escarpment, and the Erie Plain.[20] The headwaters of both the main and east branch are located on the Allegheny Plateau. The two streams descend over the steep terraces of the Portage Escarpment before reaching the relatively flat Erie Plain and draining into Lake Erie.[21] The Late stage of the Wisconsin glaciation (the last ice age) began about 85,000 years ago,[22] and in Ohio reached as far south as the Portage Escarpment before stopping.[23] This ice sheet not only shaped the relief of the land—leaving behind low rounded hills, irregular plains, and depressions that turned into wetlands[5]—but also left glacial till and erratics over most of the bedrock.[19] A low morainic ridge, the Euclid Moraine, appears east of Euclid Creek.[24][25] This morainic ridge extends 2 miles (3.2 km) to Willoughby, Ohio, from Euclid Creek.[25] A portion of the east branch flows along the south edge of this moraine.[4]

Fossils

editThe Chagrin Shale exposed by Euclid Creek contains many different arthropod fossils, including Camarotoechia, Lingula, Nucleata, Orbiculoidea, and five species of Echinocaris.[26] A lone fossil of a decapod, Palaeopalaemon, and indeterminate fragments of the crustacean Mesothyra, have also been found.[27] In 1960, a new species of lobe-finned fish, Chagrinia enodis, was found eroded out of the Chagrin Shale in the Euclid Creek Reservation.[28][29]

The Cleveland Shale along Euclid Creek is known to contain limited fossil remains. Fragments of what may be the plant Sporangites have been identified.[30] Brachiopod fossils by be found in some places in the formation's topmost layers. These are generally Lingula and Orbiculoidea, although on very rare occasions other species may be found.[31] Another fossil, once believed to be the arthropod Spathiocaris[31] but in 2017 reinterpreted to be an ammonoid aptychus,[32] may also be found. Fossil fish teeth, scales, and sometimes bones or armor are the most frequent fossils found. A review in 2008 identified 65 vertebrate taxa, represented primarily by Chondrichthyes (32 species), Placodermi (28 species), and Osteichthyes (five species).[33]

Where exposed by Euclid Creek, the Bedford Shale usually contains an extensive fossil record[34] in its bottommost part.[35] These include brachiopods like Lingula, Orbiculoidea, and the large Syringothyris bedfordensis; mollusks, particularly bivalves;[35] and Devonian fish.[36]

Main Branch

editThe Geographic Names Information System of the United States Geological Survey places the headwaters of the main/west branch of Euclid Creek between Fairmount Blvd. and Fairwood Court in Beachwood, Ohio (41°29′13.0″N 81°29′25.1″W / 41.486944°N 81.490306°W).[1] The Division of Surface Water of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency places the headwaters roughly 0.5 miles (0.80 km) to the north, on the Acacia Reservation of the Cleveland Metroparks in Lyndhurst, Ohio (41°30′18.7″N 81°29′37.3″W / 41.505194°N 81.493694°W).[2] Both are at an elevation of 1,200 feet (370 m) above mean sea level.[37] This is an area of hummocks and knolls with soil that ranges from poorly drained to moderately well drained. Soil permeability is slow to moderately slow.[38]

The main branch of Euclid Creek gently meanders over a nearly level plateau through the cities of Lyndhurst, Mayfield Heights, Richmond Heights, South Euclid, and Euclid. Soil permeability improves in Richmond Heights, South Euclid, and Euclid, ranging from moderately slow to moderately rapid.[38] After passing down the Portage Escarpment, the stream flows across the loamy, fine-sand, lacustrine sediment of the Erie Plain. Here the soil is moderately well drained and rapidly permeable.[39] Much of the main branch's streambed was determined by the Wisconsin glaciation.[19][d]

The main branch passes through some of the most densely urbanized land in Cuyahoga County. There is little remaining floodplain or intact stream banks. Poor soil permeability for much of the stream's length and the extensive impervious surfaces of the urban landscape contribute to flash flood-like stream flows. These flows inhibit the quantity and diversity of fish and aquatic insect populations.[41]

Where it drops over the Portage Escarpment, the main branch has carved a 2.75-mile (4.43 km) long gorge.[42][e] At the head (south end) of the gorge, at what is now the intersection of E. Green Road and Anderson Road, the stream tumbles over a waterfall.[45] The gorge is 100 feet (30 m)[46] to 180 feet (55 m) deep[47] and an average of 600 feet (180 m) wide.[47][46] Euclid Creek meanders across the flat bottom of the gorge,[48] where it has carved a channel 10 feet (3.0 m) deep into the alluvial soil and the shale rock.[46] Although the depth of Euclid Creek in the gorge is usually no more than ankle- to knee-deep, the stream has eroded a few deep potholes in the shale streambed, some up to 8 feet (2.4 m) deep.[49]

Emerging from this gorge about where Euclid Avenue and Chardon Road meet today, the creek meanders across the Erie Plain,[46] a relatively flat area with low, rolling hills.[50] It has carved a channel 200 feet (61 m) wide and 40 feet (12 m) deep in the Erie Plain.[51]

The mouth of Euclid Creek is located on Lake Erie at 41°35′10.2366″N 81°33′54.8166″W / 41.586176833°N 81.565226833°W,[3] 570 feet (170 m) above mean sea level.[2]

East Branch

editThe headwaters of the east branch of Euclid Creek are located near Interstate 271, about 400 feet (120 m) south of 32500 Chardon Road in Willoughby Hills, Ohio (41°34′48.4″N 81°26′57.8″W / 41.580111°N 81.449389°W).[52] The elevation at these headwaters is about 860.5 feet (262.3 m) above mean sea level. The east branch joins the main/west branch of the stream in the Euclid Creek Reservation[53][f] of the Cleveland Metroparks about 400 feet (120 m) south-southeast of the intersection of Highland Road and Metropark Drive (41°33′40.4″N 81°31′50.7″W / 41.561222°N 81.530750°W). The elevation at the confluence of the two branches is about 651.9 feet (198.7 m).

From its headwaters, the east branch flows mostly along an east-west roughly paralleling the Portage Escarpment in a deep ravine. Although the stream banks are nearly all intact and the ravine eliminates any chance for a floodplain, nearly all the tributaries of the east branch have been channelized, culvertized, and lost their floodplain due to urban development.[41]

Watershed

editThe Euclid Creek watershed is almost unique among Ohio streams in that it contains no agricultural land and is more than 80 percent developed.[54] The undeveloped land is projected to become built up within the next few decades by light industrial, office, residential, and retail construction. Residential development is likely to be apartment buildings or clustered townhouses, keeping with a national trend away from single-family homes. This will put new pressure on the water quality of Euclid Creek.[55] Cuyahoga County Airport is the largest landowner within the watershed. Six east branch tributaries travel through, under, or adjacent to the airport's 640 acres (2.6 km2).[56]

About 557.8 acres (2.257 km2) of Euclid Creek's watershed is protected. This includes the 209 acres (0.85 km2) of the Lower Euclid Creek Reservation[g] and 345 acres (1.40 km2) of the Euclid Creek Reservation. The combined reservation is one of the most heavily-used parks in the Cleveland Metroparks system. Weekend use in the summer routinely exceeds park capacity, causing compaction of soil, litter, and illegal dumping.[58] The Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District owns two conservation easements (totaling 13.8 acres (0.056 km2)) covering the headwaters of Euclid Creek in Lyndhurst and Mayfield.[59] The city of Richmond Heights owns a conservation easement over the ravine and wetlands of Verbsky Creek, and has imposed an environmental deed restriction over Claribel Creek between Richmond Heights City Hall and Richmond Heights Community Park.[60]

Few wetlands remain in the Euclid Creek watershed. Notable wetlands exist adjacent to Highland Heights Community Park, at the headwaters of a major tributary of the east branch; the Acacia Reservation; and portions of the floodplain of the east branch. The health of these wetlands is not known.[61]

Subwatersheds

editThe stream's watershed has seven distinctive subwatersheds.[62] These are:

Subwatershed 1: Erie Plains in the Nottingham neighborhood—This 23-square-mile (60 km2) area contains 3 miles (4.8 km) of the main branch stream, between Lake Erie/Lower Euclid Creek Reservation and the Euclid Creek Reservation. About 6 percent of this area is undeveloped, and more than 25 percent is covered with impervious surfaces such as parking lots or buildings. The Lake Erie coastline and Euclid Creek lacustuary have been highly modified to accommodate bathing beaches, marinas, onshore developments, parks, piers, and other developments and uses. Marshlands and an oxbow have been removed, although partial floodplain and stream restoration have occurred. Between the park and Interstate 90, Euclid Creek is highly channelized, although a riparian zone exists on either side that shields the stream from the dense urban development adjacent to it. At Villaview Road, the stream enters a long tunnel that takes it beneath Interstate 90. It briefly emerges at E. 185th Street, where the St. Clair Spillway helps keep stream velocity low.[h] The creek then enters a short tunnel to pass beneath the CSX railroad tracks. Between the railroad tracks and the Euclid Creek Reservation, much of Euclid Creek runs in a concrete channel completed as part of a flood control project. Shoaling (the accumulation of debris and sediment) has worsened in this area, reducing the effectiveness of the flood control measure.[63] Extensive illegal dumping occurs in the creek between Lakeshore Blvd. and the Euclid Creek Reservation.[62]

Subwatershed 2: Euclid Creek Reservation—This 10-square-mile (26 km2) area contains 6.8 miles (10.9 km) of the main branch stream and tributaries in the Euclid Creek Reservation. About 20 percent of this area is undeveloped, with 11 to 15 percent covered with impervious surfaces such as building rooftops, lawns, and parking lots. The watershed here is largely natural, and is enclosed in a deep, broad valley whose walls are mostly bedrock. Limited illegal dumping occurs in the park, and the creek's water quality is affected by polluted surface runoff from nearby residential areas after heavy storms.[i] Verbsky Creek,[60][64] a roughly 1.5-mile (2.4 km) long tributary, joins the east branch just before the east branch's confluence with the main branch. It runs west of Highland Road, crossing to the east of the street about 200 feet (61 m) east of the intersection of Georgetown Road and Hilltop Road. It crosses Highland Road again and turns south between Highland Ridge Drive and Donna Drive, passing through and under residential developments. Redstone Run, a 2.65 miles (4.26 km) stream,[60][64] joins Verbsky Creek just before Verbsky Creek crosses east of Highland Road. It travels east-southeast through a heavily forested ravine bordered by housing developments before turning south north of Hillcrest Drive. Flowing through a series of culverts, tunnels, and open ditches, it crosses Highland Road just west of Karl Drive, flows southeast for about 250 feet (76 m), turns south and runs between Harris Drive and Catlin Drive for about 800 feet (240 m), then runs southeast to just north of the intersection of Jefferson Lane and Monticello Place. It then travels east to Richmond Road, where its headwaters formerly began beneath what is now Richmond Town Square mall.[53]

Subwatershed 3: Lower East Branch—This 12.5-square-mile (32 km2) area contains 7.8 miles (12.6 km) of the east branch stream and four tributaries in the cities of Richmond Heights and Highland Heights. About 23 percent of this area is undeveloped, with 11 to 25 percent covered with impervious surfaces. Euclid Creek flows through a ravine with steep hillsides in this subwatershed, which has largely discouraged alterations to the stream, banks, and adjacent riparian areas. Residential development in this subwatershed consists primarily of single-family homes on large lots, which has kept impervious surfaces and population impacts low. There is some water quality impairment due to illegal dumping (primarily along Chardon Road), septic system overflows, impervious surface runoff, and poor land management (primarily erosion and fertilizer-based pollutants). A weir dam and pond obstructs the east branch west of Bishop Road.[j] Stevenson Brook, a 1.9-mile (3.1 km) long tributary, enters the east branch north of the end of Balmoral Drive. It travels largely south-southeast through a deep and heavily forested ravine, paralleling Balmoral Drive and then Douglas Blvd., before turning southeast and crossing Highland Road via a culvert at Snavely Road. The stream continues southeast in an open channel until it crosses Richmond Road north of Foxlair Trail. It travels largely east to begin in a retention pond north of Loxley Drive. The ravine adjacent to Douglas Blvd. contains a masonry dam, behind which is a small, silted-up lake. The remains of several other dam structures exist on Stevenson Brook downstream of this dam, and there may be remains of gristmills or sawmills as well.[60][64] Claribel Creek, a 1.9-mile (3.1 km) long tributary, enters the east branch northwest of the end of Country Lane. It largely parallels Royal Oak and Cary Jay Blvds., flowing southeast and then south. Southeast of the intersection of Euclid Chagrin Parkway and Cary Jay Blvd., the Mayfair Dam impounds the 4-acre (0.016 km2) Mayfair Lake. At the southern end of the lake, the stream runs through a series of channels and culverts and turns southeast and then east-southeast, crossing Highland Road east of the intersection with Richmond Park East. It then turns southeast and then south, running between Charles Place and Sunbury Drive.[60][64] A small tributary enters the east branch south of Edgemont Road, moving south between Knollwood and Bridgeport Trails and passing through a heavily wooded area south of Allendale Road before turning east to cross Richmond Road and enter the grounds of the Cuyahoga County Airport. Another tributary joins the east branch to the east of the eastern end of Brushview Drive. It travels southeast and is impeded by two weir dams before crossing White Road east of Patricia Drive. It travels south-southeast through the Cuyahoga County Airport grounds before crossing Bishop Road north of Euclid Chagrin Parkway. It continues in a largely southern direction to terminate northeast of the intersection of Bishop Road and Canterbury Lane.[66] These three large and two small tributaries originate in broad, shallow streambeds on the Appalachian Plateau,[67] then enter deep valleys as they come down the Portage Escarpment. Upper portions of the tributaries tend to be heavily impacted by development, while the lower portions are not.[66]

Subwatershed 4: Upper East Branch—This 3.2-square-mile (8.3 km2) area contains 6.3 miles (10.1 km) of the east branch stream and four tributaries in the cities of Highland Heights and Willoughby Hills. About 17 percent of this area is undeveloped, and about 11 to 25 percent is covered with impervious surfaces. Although channelization, culvertization, stream straightening, and other changes have been made to them, some portions of the tributaries retain their natural channels, banks, and floodplains.[68]

Subwatershed 5: Upper East Branch/Chagrin Plateau—This 3.5-square-mile (9.1 km2) area contains 5.3 miles (8.5 km) of the east branch in the cities of Highland Heights, Willoughby Hills, and Mayfield Heights. About 25 percent of this area is undeveloped, and about 10 to 20 percent is covered with impervious surfaces. Heavily channelized, sometimes in a concrete streambed, Euclid Creek's east branch forms just west of Interstate 271.[69][k]

Subwatershed 6: Highlands—This 2.8-square-mile (7.3 km2) area contains 3.1 miles (5.0 km) of the main branch in the cities of Lyndhurst and Mayfield Heights. About 3 percent of this area is undeveloped, and is more than 25 percent covered with impervious surfaces. This subwatershed includes a large unnamed tributary of Euclid Creek, which enters the main branch near the north end of Euclid Creek Reservation. All but the last 0.5 miles (0.80 km) of the tributary have been buried in tunnels, culvertized, and channelized. The last portion, south of Edenhurst Road, remains largely natural.[70]

Subwatershed 7: Headwaters—This 5.17-square-mile (13.4 km2) area contains 6 miles (9.7 km) of the main branch in the cities of South Euclid, Lyndhurst, and Beachwood. About 7 percent of this area is undeveloped, and it is 10 to 25 percent covered with impervious surfaces. This subwatershed is highly residential. Channelization using gabions is common in the residential areas, although a few floodplains remain north of Mayfield Road. The stream maintains its natural state as it passes through the Mayfield Sand Ridge Club (a private golf course) and through the Acacia Reservation of the Cleveland Metroparks.[71] A culvert allows the creek to pass beneath Mayfield Road[72] Upstream of the Acacia Reservation, the headwaters are extremely channelized, culvertized, and contained in a man-made streambed.[71]

Dams and in-channel obstructions

editThere were five dams on Euclid Creek as of 2017.[73][74] None of them generate power or provide flood control,[75] and all of them impede the movement of fish and aquatic resources vital to the health of Euclid Creek. The dams are:

- St. Clair Spillway—This 9-to-10-foot (2.7 to 3.0 m) high concrete spillway impedes the migration of fish on Euclid Creek, and has negatively affected the habitat around it.[76]

- David Myers Parkway Dam—This 3-to-4-foot (0.91 to 1.22 m) high concrete weir dam helps reduce the velocity of the stream as it passes between David Myers Parkway and the parking lot of The Hamptons apartment complex (west of the creek).[76]

- Mayfair Dam—This dam, located at 25959 Highland Road in Richmond Heights at the site of the former Mayfair Tennis and Swim Club, impounds the 4-acre (0.016 km2) Mayfair Lake. A pipe acts as a spillway to permit water from the lake to continue down Euclid Creek.[77] Since at least 1988, the lake has been highly eutrophic, and sediment buildup at its southern end has created a shallow delta that limits its use.[78]

- Dumbarton Blvd. Dam—This 12-to-14-foot (3.7 to 4.3 m) high masonry dam[76] is located about 400 feet (120 m) north of the intersection of Dumbarton Blvd. and Douglas Blvd. Built some time in the 1800s, it once impounded a substantial reservoir. It is silted up, and now only a small pond exists.[60]

- White Road Dam—This dam impounds roughly 600 feet (180 m) of a tributary of the east branch. A causeway, carrying the access driveway to 27511 White Road, is pierced by a culvert.[76]

The Euclid Creek Reservation Dam, an 8-foot (2.4 m) high weir dam, was removed in December 2010.[79][74] This dam helped reduce the velocity of the east branch as it passed beneath the bridge carrying Highland Avenue, significantly reducing the chance of scouring.[80]

Another 10 small detention ponds or basins exist within the Euclid Creek watershed. These ponds, which are both publicly and privately owned, are in-line with the stream and provide stormwater overflow control. Another seven to 15 privately-owned, in-line ponds on Euclid Creek provide aesthetic enhancements to landowners. The benefit these provide in terms of water quality and habitat enhancement have not been assessed. Many are filling with sediment.[81]

Culverts and channelization

editAbout 10.4 miles (16.7 km) (24.18 percent) of Euclid Creek are culverted or contained within a buried tunnel.[82] This includes 9 percent of the main branch downstream of Euclid Creek Reservation, 18 percent of the east branch, and 32 percent of the main/west branch.[6]

About 4.7 miles (7.6 km) (10.9 percent) of Euclid Creek are channelized. Channelization includes armoring (with concrete banks), confining (by making banks higher and more vertical), entrenchment (deepening the channel), gabioning, and straightening. Channelization is intended to prevent flooding during normal precipitation events. However, by confining the stream, channelization also strengthens the velocity of stream flow. This degrades fish and aquatic insect habitat, and worsens erosion and flooding during extreme precipitation events. A 2003 study by the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District (NEORSD) found that 16 miles (26 km) of Euclid Creek showed moderate to high levels of erosion due to channelization.[83]

Pollution

editPollution impairment

editAs early as 1922, scientists determined that Euclid Creek was "badly contaminated" by raw sewage.[84]

Violations of state and federal water quality laws and regulations were common in Euclid Creek throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[85] Between 1977 and 2005, nearly all illegal and illicit industrial sources of pollution were eliminated and most sewage treatment plant discharges.[86] However, pollution control has remained somewhat elusive. A 1986 study found that Euclid Creek from the confluence of the main and east branch north to Lake Erie had poor water quality. The stream had high to extremely high levels of fecal coliform (a harmful, disease-causing bacteria), phenols, total iron, and total lead.[87] The nearshore environment at the mouth of the creek was also in poor condition, with high levels of ammonia, copper, iron, manganese, nickel, total phosphorus, and zinc. There were also elevated levels of fecal coliform.[88]

The Nottingham Intake and Filtration Plant was barred from dumping waste into the creek in February 1988, although it continued to do so at least until 1990.[89] As late as 1989, the creek downstream of Euclid Avenue still ran black with chemical and oil pollution. A major nonsource pollution event in 1989 killed six salmon and 40 to 50 suckerfish in the creek, and Ohio EPA officials feared there were no more fish living in the creek.[90] A NEORSD sewage treatment plant was still venting daily into Euclid Creek in 1991 near the intersection of St. Clair Avenue and E. 185th Street.[91] The city of Willoughby Hills inaugurated a four-year sewage improvement project (the Euclid Creek Tributary Interceptor) in May 2000 designed to end sewage overflows into the east branch of Euclid Creek[92]

According to samples taken in 2000, levels of fecal coliform had dropped in the main and east branch below federal water quality standards, although several tributaries still did not meet the standard.[93] Low levels of dissolved oxygen, detected in the late 1990s and early 2000s, also appear to have been corrected.[94] Although levels of phosphorus have been significantly reduced since 1977, 30 percent of Euclid Creek areas sampled in 2003 were above the target level of 0.07 milligrams per litre (2.5×10−9 lb/cu in).[95]

As of 2005, Euclid Creek still suffered from a number of pollution and pollution-related impairments. These included: Excessive organic matter in the water, high levels of nutrients,[l] and elevated levels of disease-causing bacteria. The major sources of pollution were combined sewer overflows during periods of high precipitation,[m] nonpoint sources, septic tank overflows, and polluted stormwater.[97]

The creek continues to be impaired by disease-causing bacteria. The creek failed fecal coliform standards 42 percent of the time in 2007.[98] Fecal coliform levels at the mouth of the creek were, at times, in the thousands of parts per 100 milliliters in 2008. In comparison, most Cleveland area swimming areas had fecal coliform levels in the teens per 100 milliliters (or even lower).[99] Euclid Creek failed fecal coliform standards 59 percent of the time in 2008, making it one of the ten most polluted swimming spots in the nation, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.[100] The Natural Resources Defense Council declared Euclid Creek the most polluted stream in the Greater Cleveland region in 2011. It continued to receive more than 80 sewage overflows each summer, compared to a national average of two or three.[101] This fell to 60 times a year in 2013.[102]

Pollution control

editPollution control in Euclid Creek is the responsibility of several agencies and governments. The Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District provides sewerage in the Euclid Creek watershed, with the exception of Willoughby Hills and some unsewered areas. The Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District is the lead conservation agency overseeing the stream and its watershed.[103] Various departments and agencies of Cuyahoga County oversee water quality, watershed health, and economic and residential development. The Ohio Coastal Management Program, a division of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), is charged by the federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 with protecting and sustaining the nearshore portion of Lake Erie into which Euclid Creek empties.[104]

The Division of Surface Water of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency has designated the main branch downstream of Anderson Road a Warmwater Habitat,[n] while the remainder of the stream and its tributaries are a Limited Resource Water.[106][o] The section of Euclid Creek between Anderson Road and Euclid Avenue (that contained in the Euclid Creek Reservation) has been designated a State Resource Water,[106] which subjects it to anti-degradation rules established by the Ohio EPA.[107] Ohio EPA has also classified the majority of Euclid Creek as a Primary Contact Recreation Water,[106] indicating it should be safe for human beings to fully immerse themselves in without protection.[107]

Fishery

editFrom prehistoric times into the late 1800s, Lake Erie and its tributaries maintained a healthy fishery.[108] Euclid Creek was no exception: In the late 1800s, catfish, crappies, largemouth bass, suckers, sunfish,[109] and shorthead redhorse[110] were all caught on a regular basis in Euclid Creek. Even the occasional lake sturgeon was found in the creek.[50] In 1918, anglers were regularly catching catfish, shorthead redhorse, suckers, and yellow perch in Euclid Creek. Carp were, by then, also extremely common, and the occasional bass could still be found.[111]

Pollution and other impairments led to significant losses in the number and diversity of species by the 1960s. A 1964 study found that invertebrate species were limited to black flies, crayfish, crane flies, flatworms, leeches, mayflies, snipe flies, and seven species of midge. The only game fish which remained in the creek were the hogsucker, green sunfish, and white sucker. Coho salmon and rainbow trout (also known as steelhead) were observed entering the creek, but no spawning occurred. Pollution-tolerant minnow species were the only small fish to remain. These included the central stoneroller, common creek chub, common shiner, emerald shiner, and western blacknose dace. The east branch had a greater diversity of fish than the main branch, but was much less diverse than the nearby Big Creek or Chagrin River.[112] A 1978 survey found 11 species of frog and toad, 13 species of reptile, and 12 species of salamander in or near Euclid Creek. The most common reptile was the box turtle.[113]

Pollution impairment of Euclid Creek worsened by 1984. Water quality was poor in all portions of the stream.[114] Orthocladiinae (a subspecies of midge) and Oligochaeta (sludgeworms) constituted 65 percent of all fauna collected in or near the stream. The other invertebrates found in any number included caddisflies, mayflies, and stoneflies.[115] At a sampling site near the intersection of Green and Anderson Roads, only small numbers of fish were present, and many of these were infected with fungus or were dead.[116] The east branch of Euclid Creek exhibited the most species diversity of any segment of the stream. Its lower 2 miles (3.2 km), however, were grossly enriched due to flows from a sewage treatment plant.[117] Species diversity was about as good in the stream segment encompassed by the Euclid Creek Reservation, although the number of animals was much lower. This portion of Euclid Creek appeared to be significantly impacted by nonpoint sources.[118] All fauna in the creek was found to be moderately to highly stressed by pollution.[115]

By the late 20th century, only sucker fish survived in Euclid Creek upstream of its lacustuary, and they vanished by 2000.[109]

Fish populations in Euclid Creek remain impaired,[p] exhibiting low diversity and a high percentage of pollution-tolerant species. Top-of-the-food-chain predatory fish are absent from the creek, a common indicator of an unhealthy stream habitat.[120] Above the St. Clair Spillway, fish populations are primarily pollution-tolerant minnows[2] such as the central stoneroller, common creek chub, and western blacknose dace. Darters are absent, and this limits the capacity of the stream.[119] Below the spillway, coho salmon,[121] rainbow trout,[74][122] and smallmouth bass[2] may be found.[q] Improving the nearshore and lacustuary areas of Euclid Creek are important to increasing the diversity, health, and viability of fish populations in Euclid Creek.[125] No fish consumption advisories have been issued by the Ohio Department of Health for fish caught in Euclid Creek.[126]

Non-fish macroinvertebrate populations are less impaired than fish in Euclid Creek. The diversity, health, and number of macroinvertebrates in the lower watershed meet ODNR water quality standards, although this is not true for the upper watershed (upstream of Euclid Creek Reservation). The macroinvertebrate population is dominated by pollution-tolerant species like midges and worms, with only low levels of caddisfly, mayfly, and stonefly present.[127]

Flora and wildlife

editAlthough no wildlife survey of Euclid Creek had been conducted as of 2006, anecdotal evidence indicates that wildlife supported by the stream is typical of that found in an urban area with extensive greenspace: beaver, great blue heron, mink, red fox, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, and a small (and perhaps transient) population of coyotes in the Acacia Reservation.[7] Although no known endangered or threatened amphibian, fish, invertebrate, or mammal is known to exist in the Euclid Creek watershed, the lack of extensive studies means that their presence cannot be ruled out.[125]

Only a small number of areas, limited in size, have been studied to identify plant species within the Euclid Creek watershed. One endangered plant and two uncommon plants are known to exist in the area. Solidago puberula ("downy goldenrod") is a perennial herb listed as endangered in Ohio by ODNR. The only known stable population of this plant species in Ohio is found in Highland Heights Community Park near the headwaters of a tributary of the east branch of Euclid Creek. Hypericum gentianoides (a species of St. John's wort commonly known as "orangegrass" or "pineweed") and Rhynchospora capitellata (a species of sedge commonly known as "brownish beaksedge" or "brownish beaked-rush") are also found in wet areas of Highland Heights Community Park. This is the only known location in Cuyahoga County for either species.[125]

As a highly disturbed stream, Euclid Creek is heavily impacted by a large number of invasive plant species. Phragmites australis (a perennial grass) is extremely common north of Euclid Creek Reservation and in nearly all places where the stream banks have been disturbed. Alliaria petiolata (garlic mustard) and Reynoutria japonica (Japanese knotweed) are found extensively north of Euclid Creek Reservation. Other common invasive species throughout the watershed include autumn olive, buckthorn, several species of bush honeysuckle, Canada thistle, Japanese honeysuckle, multiflora rose, narrow-leaf cattail, purple loosestrife, reed canary grass, Russian olive, and tree of heaven.[128]

History of Euclid Creek

editNative Americans and Euclid Creek

editHuman beings first settled in northeast Ohio about 11,000 BCE, at the end of the Wisconsin Glaciation.[129] This highly nomadic hunting culture, known as Paleo-Indian, disappeared about 8,000 BCE, replaced by the nomadic hunter-gatherer Archaic culture.[130] About 2,500 BCE, this culture was in turn replaced by the semi-sedentary Woodland culture.[131][129] A warming trend in the global climate about 800 CE created more agriculturally favorable weather in Ohio, which led to the development of subsistence farming.[132] A new society emerged, the Whittlesey culture (named for 19th century Ohio scientist Charles Whittlesey).[133][r] Between 1600 and 1650 CE, the Whittlesey people disappeared.[129] The cause—absorption into another culture, disease, emigration, low birth rate, warfare, or some combination of factors—is not known. By the time the Iroquois of what is now central New York began moving along the shore of Lake Erie into northeast Ohio in 1650 during the Beaver Wars, the area was almost uninhabited. In the early and mid 1700s, the Mingo,[s] Odawa (or Ottawa), and Ouendat (or Wyandot) occupied northern Ohio after fleeing the Iroquois.[t] By 1800, Native American emigration out of the area was occurring again, and few indigenous people lived anywhere in Ohio by 1850.[137]

The Whittlesey people and their predecessors left behind well-defined trails that ran along ridges paralleling Lake Erie. These ridges are the remains of ancient beaches, deposited by prehistoric versions of Lake Erie during times when the lake water levels were much higher.[138][u] Several of these ridge trails crossed Euclid Creek, and served as the primary route by which white explorers and settlers began moving west into northern Ohio. These Native American trails are now Lakeshore Blvd., Euclid Avenue, and St. Clair Avenue.[11]

Native Americans found it difficult to access the Appalachian Plateau from the Erie Plain due to the steepness of the Portage Escarpment. Only a few natural access points existed; Euclid Creek was one of these. Modern Nottingham Road/Dille Road was originally a Native American trail which ran along the southern rim of the Euclid Creek gorge to the plateau, while modern Neff Road/Chardon Road ran along the northern rim.[11]

Euclid Creek during initial white settlement

editWhite settlement of the Euclid Creek area began when some log cabins were erected on the shore of Lake Erie east of the stream probably in the summer of 1795. Who built them, and why, is not known, and they were abandoned by the spring of 1796.[140] The area around Euclid Creek was surveyed and Euclid Township established in 1796. The surveyors, trained in mathematics, named the township after the Greek mathematician Euclid.[141] Returning east in October 1796, the survey team led by Moses Cleaveland gave the name Euclid Creek to the large creek they encountered between Doan Brook and the Chagrin River.[142]

A Connecticut Land Company survey team returned to the area in 1797 and blazed two major routes through the area, North Highway (now St. Clair Avenue) and Central Highway (now Euclid Avenue).[143][v] North Highway was renamed St. Clair Road in 1815 for Arthur St. Clair, first governor (1787-1802) of the Northwest Territory.[144]

The first permanent white settler, Joseph Burke of New York,[145] arrived in the spring or summer of 1798.[141] The second was David Dille, a New Jerseyan who formerly lived in western Pennsylvania. He arrived in November 1798 and settled on the Buffalo Road 0.5 miles (0.80 km) southwest of Euclid Creek.[146] The third permanent settler, William Coleman of Washington County, Pennsylvania, arrived in either 1803 or 1804 and settled at the mouth of Euclid Creek.[147] Abraham Bishop arrived in the area in 1809, clearing 250 acres (1.0 km2) of forest[148] west of what is now the intersection of White and Richmond Roads.[149] Garrett Thorp also settled at the mouth of Euclid Creek in 1810,[150] followed by Benjamin Thorp[151] in 1811.[152]

The Central Highway, or Buffalo Road (also known as the Cleveland-Buffalo Road), became the major route through the area. It led from the Cuyahoga River at what is now Cleveland to the area around Buffalo, New York,[153] and was cleared of trees by white explorers and settlers no later than 1810.[142] The trail was cleared of stumps and brush and turned into a dirt road by 1815,[153] and a stagecoach began running once a day between Cleveland and Buffalo.[154] The road was renamed Euclid Avenue in 1825 because it connected Cleveland and the emerging settlement of Euclid[153] (now known as the East Cleveland, Ohio, neighborhood of Collamer).[w]

Passengers on the Buffalo Road often had to have assistance in crossing Euclid Creek and its gorge.[11] Wagons could not cross the gorge loaded; they had to be unloaded and cargo carried across the creek and gorge hand. Some wagons had to be partially dismantled to safely cross. The Hermle family established a smithy and wheelwright shop next to the creek to provide these services, and other businesses provided beverages, food, and assistance in moving freight.[157] An inn, Euclid House, was built at the crossing by Abraham Farr in 1815.[154][x]

In 1810,[148] Abraham Bishop built a sawmill on his land on the east branch of Euclid Creek.[150]

The War of 1812 marks the end of the initial period of white settlement in Ohio.[158] During the war, American soldiers on horseback were stationed at the mouth of Euclid Creek to provide warning to other settlements in the area in case British ships should stop or pass by.[159] On June 19, 1813, a British naval force under Acting Commander Robert Heriot Barclay[160] anchored off Euclid Creek to wait out a storm. Sailors came ashore and killed a farmer's ox for food, apologizing for the theft.[161][y]

Euclid Creek from 1812 to 1850

editA small hamlet named Euclid Creek (hereinafter the Village of Euclid Creek) formed after the War of 1812 at the intersection of what is now Euclid Avenue and Highland Road, adjacent to Euclid Creek. Memories of the recent war led the citizens of the Village of Euclid Creek to erect a blockhouse as part of their settlement.[159] About 1816, Abraham Farr opened a tavern in a log cabin in the hamlet.[159] A Methodist church was erected in the village in 1821,[162] and a Baptist church from 1821 to 1822.[163] By 1840, the Village of Euclid Creek had three stores,[164] and the Dille family added a dry goods store and post office in 1849.[165]

A number of other important businesses opened elsewhere on Euclid Creek in the early 1800s. About 1815, Paul Condit opened a tavern in a frame house near the confluence of Claribel Creek and the east branch.[159] In 1817 or 1818, William Coleman built a gristmill near the mouth of Euclid Creek, and later a sawmill.[159] Coleman's neighbor, William Gray, erected a stoneware manufactory at the mouth of Euclid Creek about 1820. It swiftly grew to seven or eight kilns. Gray sold the works to J. & L. Marsilliott in 1823, who kept it open another 15 years.[159]

Toward the end of the 1810s, the Welch family moved from Connecticut and purchased the Euclid Creek gorge north of Monticello Blvd. This area became known as Welch's Woods,[166] and remains as part of the Euclid Creek Reservation today (as "Welsh Woods").

The national American economy underwent a boom in 1836 and 1837. A large number of people settled in Euclid Township, establishing hundreds of new farms and businesses. A city was surveyed at mouth of Euclid Creek in 1837, but no action was ever taken to build it.[167] In 1840, James Hendershot and Harvey Hussong each opened a stone quarry on Euclid Creek in what is now the Euclid Creek Reservation. Madison Sherman, who opened his quarry on the stream near them at the same time, also built a mill for cutting stone into slabs.[164] About 1840 (or just before), Ruel House, Charles Moses, and Captain William Trist opened a shipyard on the east side of the mouth of Euclid Creek where they constructed canal boats. The shipyard moved to the west side of the stream's mouth in 1845, and shifted production to the construction of schooners. The shipyard closed in 1850.[164]

Euclid Creek from 1851 to 1881

editOne of the most important infrastructure changes to affect Euclid Creek came in early 1851 when the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad (CP&A) constructed a bridge over the creek at St. Clair Avenue. Construction on the CP&A began in January 1851,[168] and by the end of the month grading had reached Willoughby.[169] The masonry arch bridge had a single 50-foot (15 m) span and extensive abutments.[168] At 40 feet (12 m) in width, the bridge was wide enough to also permit wagon traffic in addition to trains. The railroad also built a water and fuel stop, known as Euclid Depot, next to Euclid Creek at St. Clair Avenue.[51]

The railroad induced east-west road traffic to shift from Euclid Avenue to St. Clair Avenue, and the population center shifted with it.[51] The area around Euclid Depot grew so swiftly that in 1860, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland established a parish on the east bank of Euclid Creek halfway between the Village of Euclid Creek and Euclid Depot. This was the first diocesan parish outside the city of Cleveland.[170] By 1865, Euclid Depot had grown into a large village. The railroad named the village Nottingham, after CP&A general superintendent Henry Nottingham.[51][171] Although the Village of Euclid Creek continued to grow until the late 1870s, the village of Nottingham grew much more swiftly.[172]

Euclid Cemetery opened in 1864 just above the Euclid Creek floodplain south of the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Highland Road. The cemetery was created as a means of consolidating more than 80 small burial grounds, and by the time it closed had more than 4,000 graves.[173]

In 1863 or 1864,[174] attorney George Gilbert opened Camp Gilbert on the site of the former shipyard on the west bank of the mouth of Euclid Creek. Camp Gilbert was the Cleveland area's first resort. Catering to wealthy Clevelanders, the camp featured a three-story Second Empire brick headquarters, a clubhouse, creekside fishing pavilion, and campgrounds. Gilbert sold the camp in 1874 to the Ursulines of the Roman Union, a religious institute of women (nuns) engaged in education.[175] The Ursulines established Villa Angela, a boarding school for girls, at the former Camp Gilbert in 1878. A boarding school for boys, St. Joseph Seminary, opened at the site in 1886.[176]

Viticulture and winemaking on a small scale appeared in the Euclid Creek floodplain below the Appalachian Plateau after the Civil War,[177] with vineyards appearing first in the alluvial floodplain in the Euclid Creek gorge in what is now the Euclid Creek Reservation.[46] One of the first large grape-growing operations was founded in 1864 by German immigrant Louis F. Harms on 40 acres (0.16 km2) in the area now bounded by Euclid Avenue, Chardon Road, and Dansy Drive.[178] John J. and Mary Schuster founded the area's second large vineyard in 1870, southwest of the Harms vineyard across Chardon Road.[178][z] Additional quarries opened in the Euclid Creek gorge after the American Civil War. Duncan McFarland opened a quarry in 1867[172] near where Monticello Blvd. crosses Euclid Creek today. This was the first large-scale commercial stone quarry to open on Cleveland's east side.[179] His sons, James and Thomas, purchased land opposite his quarry on the west side of Euclid Creek in 1871.[179][172] John Holland and William H. Stewart founded the Forest City Stone Company[180] in 1871[181] and established a third quarry in the Euclid Creek gorge.[180] Both McFarland quarries were acquired by Forest City Stone in 1875,[179] after which the company opened a fourth quarry on the east side of the creek.[172] These quarries remained in operation until 1915.[179]

Euclid Creek from 1881 to 1916

editIn October 1882, the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad opened.[182] This railroad, which largely ran parallel to and south of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway (the former Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula),[183] passed through the Village of Euclid Creek, making it an important stopping point again. The railway, whose nickname was the "Nickel Plate",[182] built a Howe truss bridge over Euclid Creek.[184]

In 1895, the city of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County began converting Euclid Avenue from a plank road into a modern paved street. The road was widened to 100 feet (30 m) and paved from downtown Cleveland to Village of Euclid Creek.[185] The project reached Collamer in 1902, and work on the final segment to the Village of Euclid Creek began in the summer of that year.[186] The work was finished in 1902, when a new masonry arch bridge was constructed to carry Euclid Avenue over Euclid Creek. [187]

Swedish immigrants constructed a Lutheran church on the banks of Euclid Creek south of Anderson Road at Green Road in 1898.[188]

Henry Pickands, a partner in Pickands Mather and wealthy heir of Samuel Mather,[189] purchased in 1902 25 acres (0.10 km2) of land atop Chardon Hill (an area now bounded by Chardon Road, the Euclid Creek Reservation, and E. 221st Street). In 1903,[190] work was finished on a "Flemish baronial" brick mansion which he named Chestnut Hills.[191] His widow had Chestnut Hills demolished in 1938, and a Neo-Georgian style home erected on the site.[192]

In 1907, a $10,000 ($300,000 in 2023 dollars) masonry bridge was constructed to carry Lakeshore Blvd. over Euclid Creek.[193] This was followed in 1908 by a $15,000 ($500,000 in 2023 dollars) concrete bridge to carry St. Clair Avenue over Euclid Creek. This bridge was a large one, 80 feet (24 m) long and 52 feet (16 m) wide, with a 45-foot (14 m) high arch.[194]

The first major development south of the Euclid Creek gorge occurred in 1909. That year, a significant number of members of the Euclid Club in Cleveland Heights quit and founded the Mayfield Country Club in Lyndhurst.[195] In July, they purchased an initial 88 acres (0.36 km2) of land about 0.24 miles (0.39 km) northwest of the intersection of Cedar and Richmond Roads.[196] Within a year, the club owned 226 acres (0.91 km2), and had dammed Euclid Creek (which ran north through the club grounds) to provide water for the club's planned 18-hole golf course.[197] The club, reduced to 216 acres (0.87 km2), opened in July 1911.[198]

A Neoclassical house of worship was erected by Nottingham Congregational Church on the west bank of Euclid Creek near Waterloo and Nottingham Roads in 1910.[199][aa]

The first of three bridges carrying Highland Road over Euclid Creek was constructed at the north end of the Euclid Creek gorge in 1912.[200] Cuyahoga County wanted to push Highland Road southwest through the Euclid Creek Reservation, but the onset of World War I delayed the start of construction until 1920.[201] A bridge over the east branch of Euclid Creek was built about 1922.[202] Most of the remaining construction occurred in 1924,[203] although it was not until 1928 that the final portion of Highland Road (connecting it to Euclid Avenue) was paved.[204] Three Highland Road bridges remained to be constructed. Automobiles used fords to cross the creek at these points.[205]

The Village of Euclid constructed Central High School at 20701 Euclid Avenue on the east bank of Euclid Creek in 1913. It was downgraded to a junior high school in 1949, demolished in 1967, and rebuilt as Central Middle School.[173]

Although settlement and development had largely been contained to Euclid Creek below the Appalachian Plain, a few important changes were beginning to happen to the creek's headwaters. In 1913, Cleveland attorney Charles K. Arter constructed Arter House on the east bank of the main branch of Euclid Creek on what is now Curbside Road in Lyndhurst.[206] The 22-room, Late Georgian mansion sat on an elaborately landscaped 65-acre (0.26 km2) estate. The Arter children, Calvin and Charles Jr., donated the estate to the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur in 1957, who converted it into the Julie Billiart School (a school for children with learning disabilities).[207] Chester C. Bolton and his wife, Frances, established the Franchester Place estate in 1916[208] on 110 acres (0.45 km2) of land[209] on the northwest corner of Cedar and Richmond Roads.[210] In 1922, the Hawken Boys' School constructed a new school on the east bank of the main branch of Euclid Creek adjacent to the Julie Billiart School.[211] These 14 acres (0.057 km2)[212] were donated by the Boltons,[211] and a portion of them turned into athletic fields.[212]

Euclid Creek from 1917 to 1928

editThe Cleveland Metropolitan Park District (now Cleveland Metroparks) was created by state legislation in 1917. The following year, the park board proposed purchasing the main branch of Euclid Creek and its associated valley from Lake Erie south to Shaker Heights.[213] Although this plan ultimately proved unfeasible, the first 31 acres (0.13 km2) of land (consisting of most of the old Harms vineyard) was purchased in October 1920.[214][ab] By the summer of 1926, the park board had obtained title to more than a mile of Euclid Creek south of Euclid Avenue,[216] and in the fall of that year finally secured 19 acres (0.077 km2) at the northern mouth of the gorge.[217] A final 40 acres (0.16 km2) were obtained at the south end of the gorge in May 1930, giving the Cleveland Metroparks control over what is now the Euclid Creek Reservation.[218]

Cleveland Metroparks made almost no improvements to the Euclid Creek gorge while it was assembling the land for the Euclid Creek Reservation.[219] On November 21, 1933, the federal government approved the establishment of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in the Euclid Creek Reservation. A barracks was erected at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Highland Road,[219] and over the next three years the CCC workers cleared land, planted trees, and built picnic areas, trails,[219] and parking lots.[220] Most importantly, they constructed three bridges for Highland Road (eliminating the last fords on that street) and built what is now Metro Park Drive (also known as Euclid Park Road and Metropolitan Park Blvd.)[219][221] Workers also armored and channelized the creek downstream of Villaview Road by lining the banks with stone blocks.[222] Euclid Creek Reservation was formally dedicated and opened on June 24, 1936—the first public opening of any unit in the Cleveland Metroparks system. The CCC camp became veterans' housing in 1942, and was demolished in 1944.[219]

Other open spaces on Euclid Creek were being developed, however. The Harms family sold the remaining 26.5 acres (0.107 km2) of their vineyard to the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in June 1920.[223] The nuns erected Our Lady of Lourdes Shrine at the site, which was dedicated on May 30, 1926.[224] In 1921,[209] Dudley S. Blossom, Director of Public Health and Welfare for Cuyahoga County, and his wife, Elizabeth (Frances Payne Bolton's sister), purchased a 22-acre (0.089 km2) estate just south of the Bolton's Franchester Place.[225] Over the next year,[209] the couple built a Tudor Revival home on the estate.[225] Between 1922 and 1927, the Blossoms added a service compound that consisted of two small homes for estate workers, a garage, and a stable for horses.[226] Elizabeth Blossom was an avid cultivator of flowers, and established a wild garden in the small ravine through which Euclid Creek flowed on the Blossom estate.[227] After Dudley Blossom's death in 1938, Elizabeth had the main house torn down and a Neo-Georgian style home erected in its place.[225]

Another development which impacted the headwaters of Euclid Creek opened in 1923. This was the Acacia Country Club, located on the northeast corner of Cedar and Richmond Roads. Founded in 1921, a temporary clubhouse and the first nine holes of the 302-acre (1,220,000 m2) club opened in May 1923.[228][229][230][231][ac] Press reports say that the owners laid 16 miles (26 km) of tile drain to channel water into Euclid Creek.[230] The final nine holes opened in July 1924,[233][ad] and the permanent clubhouse in May 1925.[235]

Euclid Creek from 1928 to 1945

editRapid development atop the Appalachian Plateau began to affect both the main and east branches of Euclid Creek after 1920.

In 1928, the Curtiss-Wright corporation purchased 271 acres (1.10 km2) of land east of Richmond Road from the Richmond Estates Land Company. The company opened a dirt-runway airport there, and named it Herrick Field after Myron T. Herrick.[ae] A hangar was erected in 1929, but area residents won a federal injunction declaring the airfield a noise nuisance and public danger.[236] It closed on August 1, 1930.[237] Cuyahoga County purchased the sod airfield in 1946 for $200,000 ($3,100,000 in 2023 dollars) and it reopened on May 30, 1950.[238] The airport expanded to 470 acres (1.9 km2) by 1963,[239] 585 acres (2.37 km2) by 1970,[240] 625 acres (2.53 km2) by 1981,[241] and 640 acres (2.6 km2) by 1999[242]—encompassing several tributaries of the east branch.

The 1902 masonry bridge over Euclid Creek was rebuilt in 1932.[243]

A portion of Claribel Creek, a tributary of Euclid Creek, was channelized in 1933 when Ohio Villa, a 100-acre (0.40 km2) country club opened northeast of the corner of Richmond and Highland Roads. The club's owner, the Italian-American Brotherhood Club, was forced to close the facility in 1942 after its major investors were found to be bank robbers with connections to the Cleveland crime family. It reopened as the Richmond Country Club in 1942,[244] and Mayfair Dam erected the same year to create Mayfair Lake.[78] After the clubhouse burned in 1953,[244] the site was taken over by the Mayfair Tennis and Swim Club (a Jewish health club).

In 1942, the Sisters of St. Joseph of St. Mark purchased the 30.5-acre (0.123 km2) Pickands estate. The 1938 Pickands mansion was converted into the Mount St. Joseph Nursing Home.[245]

Euclid Creek from 1945 to 1970

editThe city of Cleveland began construction on the Nottingham Intake and Filtration Plant on Euclid Creek in July 1947.[246] The project, designed to provide the city's fast-growing east side with fresh water from Lake Erie rather than from Euclid Creek, other streams, and groundwater wells, was first proposed in 1925 and set for completion in 1930.[247] In 1930, the city condemned 80 acres (0.32 km2) of land on the east bank of Euclid Creek between the Nickel Plate tracks and St. Clair Avenue.[248] Construction was delayed by the onset of the Great Depression,[249] and the plant finally opened in the early fall of 1951.[250]

While the water filtration plant was under construction, the Cuyahoga County Airport opened in May 1950.[238]

In 1954, Cuyahoga County and the city of South Euclid approved the construction of a bridge over Euclid Creek to link Monticello Blvd. and Wilson Mills Road.[251] Officials had spent several years debating whether to build a low-level bridge or a high-level span. The high-level span was finally approved, and the $1.2 million ($13,600,000 in 2023 dollars) structure spanning the 400-foot (120 m) wide ravine opened in December 1955.[109][252]

Construction of Interstate 271 began in November 1960.[253] The first segment, from Willoughby Hills to Wilson Mills Road, was under construction by April 1961, with construction on the segment from Wilson Mills Road to Fairmount Blvd. set to begin in the fall of 1961 and the segment from Fairmount Blvd. to Harvard Road for late 1961.[254] The entire route (now extending as far south as Chagrin Blvd.) opened in November 1962.[255] The freeway crossed two tributaries of the east branch (one of them twice),[256] and these waters were rechanneled into a man-made ditch by the freeway's construction.[69] The completion of Interstate 271 spurred a development boom on the east side of Cuyahoga County, greatly affecting Euclid Creek's headwaters.[257]

Construction of Interstate 90 and the Lakeland Freeway through the city of Euclid began in the spring of 1961.[258] Euclid Creek was straightened, cutting off a strong meander bounded by Neff Road, Villaview Road, Nottingham Road, and the old Lake Shore railroad tracks. The meander was filled in and a cloverleaf interchange built on the site.[109] Beneath the freeway, Euclid Creek was culverted[259] and a 900-foot (270 m) long concrete channel constructed to replace the natural streambed.[222] Work on the Lakeland Freeway in Euclid was finished in November 1962.[255][260] Construction of the culvert proved to be a turning point in how communities treated water in Cuyahoga County. Previously, streambeds were bridged. Afterward, streams were routinely buried in tunnels or culverted.[261]

The headwaters of Redstone Run, one of the east branch's major tributaries, were affected by construction in 1962. That year, the Glazer-Marotta Companies won zoning approval to construct a shopping mall (now Richmond Town Square) on the northeast corner of the intersection of Richmond Road and Monticello Blvd. The company agreed to spend as much as 2 percent of the mall's cost in culvertizing, pumping, and rerouting the headwaters of Redstone Run.[262] Initially, the $8 million ($80,600,000 in 2023 dollars) project was intended to cover just 45 acres (0.18 km2) of land in the watershed,[263] but the project was expanded until it cost $42 million ($412,600,000 in 2023 dollars) and covered 105 acres (0.42 km2).[264] The Richmond Mall opened in September 1966.[265] A year after the mall project was announced, construction began on St. Gregory of Narek Armenian Church across the street at 678 Richmond Road.[266] It opened in April 1964,[267] further impeding the headwaters of Redstone Run.

In 1966, a new development in Beachwood impacted the headwaters of the main branch of Euclid Creek. That year, the Jewish Orthodox Home for the Aged moved from Lakeview Road in Cleveland's Glenville neighborhood to a large new site at 27100 Cedar Road in Beachwood. The organization, now called Menorah Park Jewish Home for the Aged, constructed a one-story nursing home.[268] Over the next half century, Menorah Park constructed an extensive senior living campus. The R.H. Myers Apartments, finished in 1978, contained 207 units in a four-story tower, 10-story tower, and one-story communal area.[269] Stone Gardens, an assisted living facility, opened in 1994,[270] and Wiggins Place, a second assisted living community, in 2004.[271]

Euclid Creek from 1970 to 1995

editVilla Angela completed a Modernist school building for its girls' academy on its 55-acre (0.22 km2) property at the mouth of Euclid Creek[272] in April 1972.[273] It opened to students in September 1972.[274] The 1864 school building was razed in late 1972.[275]

In 1976, the Rouse Co. announced it would construct a $25 million ($133,900,000 in 2023 dollars) shopping mall, Beachwood Place, on 50 acres (0.20 km2) of land owned by the Ratner family on the southeast corner of Richmond and Cedar Roads.[276] The mall (whose cost rose to $30 million ($160,600,000 in 2023 dollars) within four months)[277] began construction atop a portion of the headwaters of the main branch of Euclid Creek[278][279] in August 1977.[280] Much of the channel was altered and realigned prior to construction.[281] Beachwood Place opened in late August 1978.[282]

In 1981, after more than a decade of flooding and discussion about how to correct it,[283] the United States Army Corps of Engineers acted to reduce erosion and flooding on Euclid Creek between Villaview Road and Lakeshore Blvd. The narrow-arched, culverted Lakeshore Blvd. bridge over Euclid Creek was replaced with a 100-foot (30 m) wide span[284] at a cost of $1 million ($3,200,000 in 2023 dollars).[285][af] The city of Cleveland spent another $650,000 ($2,100,000 in 2023 dollars) to purchase 25 acres (0.10 km2) of bank along the stream between Euclid Avenue and the lakeshore.[285] The 1930s-era stone block reinforcing the bank was removed,[287] the 1.3 miles (2.1 km) of creek between Lakeshore Blvd. and the lake was straightened,[283] the creek north of Euclid Avenue widened and deepened,[285] and an additional 600 feet (180 m)[222] of the banks and streambed covered in concrete[283][285] at a cost of $2.12 million ($6,500,000 in 2023 dollars).[283][ag] The Corps also constructed a levee along the east bank of Euclid Creek between Lakeshore Blvd. and E. 179th Street at a cost of about $2.23 million ($6,800,000 in 2023 dollars).[283][ah]

Minor changes to the Euclid Creek lacustuary came in 1985, when The Trust for Public Land purchased a small parcel from Villa Angela to expand Euclid Beach.[288] Two years later, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland announced tentative plans to merge Villa Angela with St. Joseph Academy,[289] the former St. Joseph's Seminary which had become all-male high school and relocated 2 miles (3.2 km) to the northeast at 18491 Lakeshore Blvd.[290] As Cuyahoga County embarked on a $4.5 million ($12,100,000 in 2023 dollars), state-funded Euclid Creek flood control project in the fall of 1987, the city and state began planning to purchase the Villa Angela lands and convert them to a public park.[291]

Major changes to the Euclid Creek lacustuary when Villa Angela closed in August 1989,[288] setting in motion a major change in the way the lacustuary of Euclid Creek was managed. In July 1989, The Trust for Public Land (with financial assistance from four other foundations) purchased 26 acres (0.11 km2) of land from Villa Angela and Associated Estates (a real estate development company) for $2.45 million ($6,000,000 in 2023 dollars). This land was then purchased by ODNR for use as parkland.[292][ai] The state also spent $607,000 ($1,400,000 in 2023 dollars) on gabions to stabilize Euclid Creek's banks between Anderson and Mayfield Roads, and another $250,000 ($600,000 in 2023 dollars) to straighten and add retaining walls to Euclid Creek's Redstone Run tributary between Schaefer Park and Roland Park in Lyndhurst.[293] The Cleveland Public Library (CPL) system purchased 1 acre (0.0040 km2) of land from Villa Angela in September 1990 for $160,000 ($400,000 in 2023 dollars) for the construction of a new branch library to replace its Nottingham and Memorial branches (which it intended to merge).[295] In May 1991, CPL purchased an additional 14.6 acres (0.059 km2) of Villa Angela land (which included the 1973 school building) for $2.2 million ($4,900,000 in 2023 dollars).[296][297] The library system agreed to keep a part of its acreage parkland, and allowed ODNR to construct a road through this area to provide improved access to the new park at the creek's mouth.[296] CPL spent the next three years and $6.1 million ($12,500,000 in 2023 dollars) remodeling the school into a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) branch library and 115,000-square-foot (10,700 m2) administrative structure that provided storage for seldom-used books, the community service department, the technical services department, and training and conference facilities.[298] The new Nottingham-Memorial Branch Library (the largest branch in the CPL system) opened on August 8, 1994.[299]

In 1991, Montefiore Home, a nursing home serving the Jewish community, opened a 240-room facility adjacent to the south side of Menorah Park in Beachwood, further impacting the headwaters of the main branch of Euclid Creek.[300] The facility underwent a major expansion in 2005.[301] Montefiore added the eight-unit Willensky Residence assisted living facility for individuals with Alzheimer's disease in 2012,[302] and expanded it to 25 units in 2015.[303] Another expansion of the Montefiore campus, the six-unit Maltz Hospice House, opened in April 2015.[304]

The 1932 bridge over Euclid Creek was rehabilitated in 1991 at a cost of $1 million ($2,200,000 in 2023 dollars).[243] The bridge carrying Anderson Road over Euclid Creek underwent significant repair of its deck in 1991 as well.[305]

ODNR constructed a two-lane road and two parking lots[aj] in the new park at the mouth of Euclid Creek in 1993 and 1994 at a cost of $6.5 million ($13,700,000 in 2023 dollars).[307] Euclid Creek was bridged with a new vehicular-pedestrian bridge near the creek mouth to provide access to the parking lots.[306] Another $2.3 million ($4,700,000 in 2023 dollars) was spent in 1994 adding improvements such as a new beach,[ak] a 1-mile (1.6 km) long biking/hiking path, new boat docks, a second two-lane boat launch ramp, breakwater, and a fishing pier, and the park was administratively merged with the Cleveland Lakefront State Park.[306][308][al] The fishing pier, which was on the west side of the mouth of Euclid Creek, was completed in the spring of 1995. The creek mouth was dredged when the pier was completed.[309]

Euclid Creek from 1995 to 1999

editWidening of Interstate 271 to eight from four lanes, which was completed in 1993, led to major new flooding problems on Euclid Creek. The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) had moved forward with the project without constructing any new flood control measures after concluding that the interstate highway's existing flood control measures, designed in the 1950s and 1960s, were adequate for an eight-lane freeway. In October 1994, the Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District (CS&WCD) concluded that the widening project had contributed to extensive flooding in Willoughby Hills.[310] According to CS&WCD studies, ODOT engineers did not account for the increased runoff into Euclid Creek caused by extensive new impervious development, channel straightening, and channelization in Beachwood, Lyndhurst, and Highland Heights since the design of Interstate 271.[256] An investigation by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 1997 found that Beachwood had for years permitted construction within the Euclid Creek flood plain that did not follow federal regulations. Nor had the city alerted FEMA to the alterations made to the stream's channel (as required by law) during the construction of Beachwood Place in 1977 and 1978.[281]

In November 1997, a hydrological study (paid for by the city of South Euclid) blamed the widening of I-271 and overdevelopment in Beachwood for significantly worse erosion problems in the Euclid Creek Reservation and flooding in communities downstream from Beachwood.[am] Stormwater velocity had increased from 60 percent to 90 percent since 1959, and the volume of stormwater runoff from 40 percent to 80 percent, even as storm and regular rainfall remained constant.[279] A second study, issued in June 1999, concluded that the city of Beachwood had not followed standard stormwater management practices since 1980,[311] and the two stormwater detention basins it had constructed were of only minimal effectiveness.[312]

In response to the Euclid Creek flooding and other extensive combined sewer problems in the greater Cleveland area, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District initiated in 2001 a $1 billion ($1,720,700,000 in 2023 dollars) project to construct 40 miles (64 km) of underground detention basins, tunnels, and sewers on Cleveland's East Side.[313] The first phase of the project was the construction of the Euclid Creek Storage Tunnel, a 24-foot (7.3 m) diameter,[314] 3-mile (4.8 km) long underground stormwater storage basin that stretched from the Euclid Creek Reservation northwest to the city of Bratenahl.[315][an] The Euclid Creek Storage Tunnel was completed in September 2015,[314] and became operational in June 2016 when the Easterly Tunnel Dewatering Pump Station went online. The pumping station was designed to empty the Euclid Creek Storage Tunnel as well as the as-yet incomplete Dugway Storage Tunnel and Doan Valley Storage Tunnel and divert their stored stormwater to the Easterly Wastewater Treatment Plant.[316][ao]

2001 also saw Cleveland and nine east-side suburbs form the Euclid Creek Watershed Council to work together on Euclid Creek and combined sewer flooding. Water quality and velocity in Euclid Creek was of a major concern to the group, which tentatively set plans to restore meanders to the stream as an initial goal.[317]

Euclid Creek in the 21st century

editIn 2002, a new nonprofit advocacy group, the Euclid Creek Watershed Council, formed to address flooding and water quality issues along Euclid Creek.[318] The group began working closely with the Euclid Creek Watershed Coordinator, one of 319 watershed coordinators funded by ODNR. Housed within the Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District, the Watershed Coordinator acts both as the secretary of the Euclid Creek Watershed Council and its staff person.[319]

The headwaters of the main branch of Euclid Creek were significantly impacted by the construction of the Legacy Village lifestyle center in Lyndhurst in 2003. TRW Inc. had purchased the Bolton estate in 1985 and the Blossom estate in 1992.[ap] Although the Bolton mansion was retained, the company demolished the Blossom house (but not the service compound structures) in 1993.[209] Within a few years, TRW resolved to close its operations in Lyndhurst and sell its property to developers.[226] Lyndhurst voters narrowly approved rezoning the area to retail from residential in November 2000. TRW donated most of the old Bolton estate to the Cleveland Clinic in 2002,[225] selling the remaining 67 acres (270,000 m2) to First Interstate Properties, a real estate development firm.[209]

Legacy Village opened on October 24, 2003.[209] Only 60 percent (40.2 acres (163,000 m2)) of the land obtained from TRW was developed. Some of the remaining land was used as a buffer between the mall and local residences, while 25 acres (100,000 m2) of woodlands and wetlands were retained and restored (including the old Bolton wild garden).[227] Land west of Legacy Village, located between the shopping center and a luxury development known as "The Woods", contained a small main branch tributary. The Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District was granted a conservation easement over this land to preserve it.[320] First Interstate restored the Blossom service compound, which was then listed on the National Register of Historic Places in February 2004.[227]

Dam removal on Euclid Creek became a priority for the stream's restoration advocates in the mid-2000s. The Ohio EPA released in 2005 a study (required by the federal Clean Water Act) which concluded that alteration or removal of the St. Clair Spillway would greatly improve invertebrate and fish populations in the creek.[9] Cost of removing the spillway proved prohibitive, however: A 2010 study estimated this cost at $2 million ($2,800,000 in 2023 dollars).[74] The Euclid Creek Reservation Dam was removed at a cost of $527,000 ($700,000 in 2023 dollars) in 2010 after a five-year effort. Part of the cost went to restoring the stream after the dam's removal.[318]

Despite improvements, by 2010 flash flood-like runoff remained an issue for Euclid Creek. The Plain Dealer newspaper called the Euclid Creek Reservation "the region's catch-basin for storm water runoff". Flash-like flooding was so severe that the park had been extensively damaged and erosion control within the park was failing.[321]

Cleveland Metroparks purchased the Acacia Country Club in 2012 and began restoring Euclid Creek within the new park boundaries. Acacia's owners agreed to sell the land to The Conservation Fund for $14.75 million ($19,600,000 in 2023 dollars),[322] despite opposition from Lyndhurst Mayor Joseph Cicero and a group of real estate developers (who offered $16 million for the land).[323] An anonymous donor financed The Conservation Fund's acquisition, with the stipulation that the land no longer be used as a golf course but rather be converted into a nature park.[324] A month later, The Conservation Fund donated the land to Cleveland Metroparks. The nonprofit also made a $300,000 ($400,000 in 2023 dollars) donation to the park agency to help with the transition, and pledged another $200,000 ($300,000 in 2023 dollars) once restoration plans had been finalized.[325] One of the first projects Cleveland Metroparks undertook at Acacia was the restoration of Euclid Creek. This involved removing the culverts through which the creek flowed, rebuilding a meandering channel, removing armor and channelization structures, and reconnecting the stream to its floodplain. Projects the following year included removing the tile drainage system which underlay the park, building swales throughout the park, and planting extensive new trees, shrubs, native plants, and grasses around Euclid Creek and elsewhere in the new park. The work was paid for with $1.5 million in grants from the Ohio EPA and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The Cuyahoga Soil and Water Conservation District called it the "single largest restoration effort in the history of the watershed".[324]

A pedestrian-only bridge was constructed over the mouth of Euclid Creek by Cleveland Metroparks in 2016. The 1992 fishing pier at Lower Euclid Creek Reservation was demolished in the fall of 2016, and a new 220-foot (67 m) pier constructed in 2017.[326]

NEORSD began a Euclid Creek Shoaling Removal Project in November 2017. The two-month-long project removed gravel, sand, wood, and trash which degraded habitat and inhibited water flows in Euclid Creek's manmade channel between Lakeshore Boulevard and Villaview Road.[222]

References

edit- Notes

- ^ Between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago, Lake Erie was roughly 15 feet (4.6 m) lower than it is today.[10] Euclid Creek's mouth was then located much farther north of its present location, and the channel was about 20 feet (6.1 m) deeper. When lake water levels rose, they drowned the mouth of the creek as far north as present Lakeshore Blvd., creating the lacustuary the creek's mouth.[11]

- ^ The age of the Berea Sandston is difficult to estimate due to the lack of diagnostic fossils. The age given is therefore a very rough approximation.[17]