Esenbeckia runyonii is a species of flowering tree in the citrus family, Rutaceae, that is native to northeastern Mexico,[2] with a small, disjunct population in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas in the United States.[3] Common names include Limoncillo and Runyon's Esenbeckia.[4] The specific epithet honors Robert Runyon, a botanist and photographer from Brownsville, Texas,[5] who collected the type specimen from a stand of four trees[4] discovered by Harvey Stiles on the banks of Resaca del Rancho Viejo, Texas, in 1929. Conrad Vernon Morton of the Smithsonian Institution received the plant material and formally described the species in 1930. Some consider it a synonym of E. berlandieri Baill. ex Hemsl..[4][6]

| Esenbeckia runyonii | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Esenbeckia |

| Species: | E. runyonii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Esenbeckia runyonii | |

Description

editRunyon's Esenbeckia is a small, multi-trunked tree that slowly grows to around 30 ft (9.1 m) in height and 2 ft (0.61 m) in diameter. The dark green, glossy leaves are trifoliate, with each leaflet 1–3 in (2.5–7.6 cm) long.[7] Bark is whitish[8] except for irregular copper-colored patches that exfoliate to reveal the greenish, lenticel-dotted inner bark, much like American sycamores. The star-shaped white flowers[7] are about 0.25 in (0.64 cm) in width and have four or five sepals, with an equal number of petals and stamens. The flowers form in broad, terminal panicles and are produced biannually, once in late spring and once in September. The fruit is a thick-skinned,[8] woody capsule roughly 1 in (2.5 cm) in length that has five carpels. When mature, carpels dehisce (break apart) to eject black, up to 1⁄3 in (0.85 cm) long seeds.[7] Green capsules are distinctively orange scented,[8] while leaves smell like lemons.[9]

Habitat and range

editThe vast majority of E. runyonii trees occur in Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí and northwestern Hidalgo in northeastern Mexico.[2] It is relatively common on scree slopes in deep, protected canyons at elevations of 2,000–3,000 ft (610–910 m) in the Sierra Madre Oriental, but can also be found in the ecotones between Tamaulipan matorral and forested canyons.[7] A few individuals[4] exist in the Tamaulipan mezquital along resacas in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas in the United States. It is possible that this disjunct population arose from seeds dispersed by flooding of the Rio Grande's drainage basin in the Sierra Madre Oriental.[7]

Uses

editPost-sized branch cuttings from Limoncillo are planted in the ground during the dry season by farmers in Mexico. Eventually these will take root, forming living fences. Showy foliage[7] and blooms make it an attractive ornamental.[8]

References

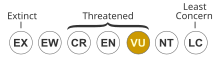

edit- ^ Fuentes, A.C.D.; Martínez Salas, E.; Ramos Álvarez, C. (2019). "Esenbeckia runyonii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T141522638A141522836. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T141522638A141522836.en. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "Esenbeckia runyonii". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Hagne, Martin (November 2008). "Native Citrus Trees of the Lower Rio Grande Valley" (PDF). The Sabal. 25 (8). Native Plant Project: 3–5.

- ^ a b c d "Limoncillo Runyon's Esenbeckia Esenbeckia runyonii Rutaceae". TAMUK Herbarium. Texas A&M University-Kingsville. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ Little, Elbert Luther (1953). Check List of Native and Naturalized Trees of the United States (Including Alaska). Vol. 41. United States Department of Agriculture. p. 179.

- ^ "Esenbeckia runyonii Morton". ITIS Standard Reports. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Nokes, Jill (2001). How to Grow Native Plants of Texas and the Southwest (2 ed.). University of Texas Press. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-0-292-75573-4.

- ^ a b c d Everett, Thomas H. (1981). The New York Botanical Garden Illustrated Encyclopedia of Horticulture. Vol. 4. Courier Corporation. p. 1268. ISBN 978-0-8240-7234-6.

- ^ "Talking Trees". Plants of South Texas. Quinta Mazatlan. Archived from the original on 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

External links

editData related to Esenbeckia runyonii at Wikispecies