This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

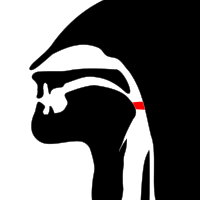

A pharyngeal consonant is a consonant that is articulated primarily in the pharynx. Some phoneticians distinguish upper pharyngeal consonants, or "high" pharyngeals, pronounced by retracting the root of the tongue in the mid to upper pharynx, from (ary)epiglottal consonants, or "low" pharyngeals, which are articulated with the aryepiglottic folds against the epiglottis at the entrance of the larynx, as well as from epiglotto-pharyngeal consonants, with both movements being combined.

Stops and trills can be reliably produced only at the epiglottis, and fricatives can be reliably produced only in the upper pharynx.[why?][citation needed] When they are treated as distinct places of articulation, the term radical consonant may be used as a cover term, or the term guttural consonants may be used instead.

Pharyngeal consonants can trigger effects on neighboring vowels. Instead of uvulars, which nearly always trigger retraction, pharyngeals tend to trigger lowering. For example, in Moroccan Arabic, pharyngeals tend to lower neighboring vowels (corresponding to the formant 1).[1] Meanwhile, in Chechen, it causes lowering as well, in addition to centralization and lengthening of the segment /a/.[2]

In addition, consonants and vowels may be secondarily pharyngealized. Also, strident vowels are defined by an accompanying epiglottal trill.

Pharyngeal consonants in the IPA

editPharyngeal/epiglottal consonants in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA):

| IPA | Description | Example | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Orthography | IPA | Meaning | ||

| ʡ | voiceless* pharyngeal (epiglottal) plosive | Aghul, Richa dialect[3] | йагьІ | [jaʡ][citation needed] | 'center' |

| ʜ | voiceless pharyngeal (epiglottal) trill | хІач | [ʜatʃ] | 'apple' | |

| ʢ | voiced pharyngeal (epiglottal) trill | Іекв | [ʢakʷ] | 'light' | |

| ħ | voiceless pharyngeal fricative | Arabic | حَـر | [ħar] | 'heat' |

| ʕ | voiced pharyngeal fricative** | عـين | [ʕajn] | 'eye' | |

| ʡ̯ | pharyngeal (epiglottal) flap | Dahalo | [nd̠oːʡ̆o] | 'mud' | |

| ʕ̞ | pharyngeal approximant | Danish | ravn | [ʕ̞ɑʊ̯ˀn] | 'raven' |

| ʡʼ | pharyngeal (epiglottal) ejective | Dargwa | |||

| ʡ͡ʜ | Voiceless epiglottal affricate | Haida (Hydaburg Dialect) | x̱ung[4] | [ʡ͡ʜuŋ] | 'father' |

| ʡ͡ʢ | Voiced epiglottal affricate | Somali[5] | cad | [ʡʢaʔ͡t] | 'white' |

- *A voiced epiglottal stop may not be possible. When an epiglottal stop becomes voiced intervocalically in Dahalo, for example, it becomes a tap. Phonetically, however, both voiceless and voiced affricates and off-glides are attested: [ʡħ, ʡʕ] (Esling 2010: 695).

- ** Although traditionally placed in the fricative row of the IPA chart, [ʕ] is usually an approximant. Frication is difficult to produce or to distinguish because the voicing in the glottis and the constriction in the pharynx are so close to each other (Esling 2010: 695, after Laufer 1996). The IPA symbol is ambiguous, but no language distinguishes fricative and approximant at this place of articulation. For clarity, the lowering diacritic may used to specify that the manner is approximant ([ʕ̞]) and a raising diacritic to specify that the manner is fricative ([ʕ̝]).

The Hydaburg dialect of Haida has a trilled epiglottal [ʜ] and a trilled epiglottal affricate [ʡʜ]~[ʡʢ]. (There is some voicing in all Haida affricates, but it is analyzed as an effect of the vowel.)[citation needed]

For transcribing disordered speech, the extIPA provides symbols for upper-pharyngeal stops, ⟨ꞯ⟩ and ⟨𝼂⟩.

Place of articulation

editThe IPA first distinguished epiglottal consonants in 1989, with a contrast between pharyngeal and epiglottal fricatives, but advances in laryngoscopy since then have caused specialists to re-evaluate their position. Since a trill can be made only in the pharynx with the aryepiglottic folds (in the pharyngeal trill of the northern dialect of Haida, for example), and incomplete constriction at the epiglottis, as would be required to produce epiglottal fricatives, generally results in trilling,[why?] there is no contrast between (upper) pharyngeal and epiglottal based solely on place of articulation. Esling (2010) thus restores a unitary pharyngeal place of articulation, with the consonants being described by the IPA as epiglottal fricatives differing from pharyngeal fricatives in their manner of articulation rather than in their place:

The so-called "Epiglottal fricatives" are represented [here] as pharyngeal trills, [ʜ ʢ], since the place of articulation is identical to [ħ ʕ], but trilling of the aryepiglottic folds is more likely to occur in tighter settings of the laryngeal constrictor or with more forceful airflow. The same "epiglottal" symbols could represent pharyngeal fricatives that have a higher larynx position than [ħ ʕ], but a higher larynx position is also more likely to induce trilling than in a pharyngeal fricative with a lowered larynx position. Because [ʜ ʢ] and [ħ ʕ] occur at the same Pharyngeal/Epiglottal place of articulation (Esling, 1999), the logical phonetic distinction to make between them is in manner of articulation, trill versus fricative.[6]

Edmondson et al. distinguish several subtypes of pharyngeal consonant.[7] Pharyngeal or epiglottal stops and trills are usually produced by contracting the aryepiglottic folds of the larynx against the epiglottis. That articulation has been distinguished as aryepiglottal. In pharyngeal fricatives, the root of the tongue is retracted against the back wall of the pharynx. In a few languages, such as Achumawi,[8] Amis of Taiwan[9] and perhaps some of the Salishan languages, the two movements are combined, with the aryepiglottic folds and epiglottis brought together and retracted against the pharyngeal wall, an articulation that has been termed epiglotto-pharyngeal. The IPA does not have diacritics to distinguish this articulation from standard aryepiglottals; Edmondson et al. use the ad hoc, somewhat misleading, transcriptions ⟨ʕ͡ʡ⟩ and ⟨ʜ͡ħ⟩.[7] There are, however, several diacritics for subtypes of pharyngeal sound among the Voice Quality Symbols.

Although upper-pharyngeal plosives are not found in the world's languages, apart from the rear closure of some click consonants, they occur in disordered speech. See voiceless upper-pharyngeal plosive and voiced upper-pharyngeal plosive.

Distribution

editPharyngeals are known primarily from three areas of the world:

- the Middle East, North Africa and the Horn of Africa, in the Semitic, Berber (mostly in borrowings from Arabic[10]) and Cushitic branches of the Afroasiatic language family

- the Caucasus, in the Northwest, and Northeast Caucasian language families

- British Columbia, in the Northern Haida dialects, in the Interior Salish branch of the Salishan language family, and in the southern branch of the Wakashan language family.

There are scattered reports of pharyngeals elsewhere, as in:

- Indo-European languages:

- According to the laryngeal theory, Proto-Indo-European might have had pharyngeal consonants.

- Indo-Iranian:

- Iranian:

- Nuristani:

- Northern:

- Kalasha-ala: [ħ][b], [ʕ][b]

- Kamkata-vari:

- Kamviri dialect: [ħ][b], [ʕ] [b]

- Northern:

- Indo-Aryan:

- Northern

- Eastern

- Bengali-Assamese

- some eastern Bengali dialects: [ʜ][e]

- Bengali-Assamese

- Western:

- Domari: [ħ], [ʕ]

- Northwestern:

- Slavic:

- Germanic:

- the approximant [ʕ̞] is a realization of /r/ in such Germanic languages as Danish and Swabian German.

- Romance:

- Italo-Western:

- Western:

- Iberian:

- West:

- Galician-Portuguese:

- Castilian:

- West:

- Iberian:

- Western:

- Italo-Western:

- Austronesian languages:

- Niger–Congo languages:

- Nilo-Saharan languages:

- Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages:

- the language isolate Kusunda of Nepal: [ʕ][q]

- the Papuan language Teiwa: [ħ]

- the Guaicuruan language Pilagá: [ʕ]

- the Mayan language Achi: [ʕ]

- the Siouan language Stoney (Nakoda): [ħ][r], [ʕ][r]

- the Achumawi language of California: [ʜ]

- ^ Mostly occurs in words of Arabic origin, mostly in word-initial position

- ^ a b c d e f g h Borrowed from Arabic

- ^ a b Appear mostly in loanwords. Native words with those sounds are rare and mostly onomatopoeic.

- ^ Historically derives from /s/ and occurs word-finally, e.g. [ɡʱɑːħ] "grass", [biːħ] "twenty"

- ^ Mainly realized as such in very eastern regions; often also debuccalized or phonetically realised as /x/. Corresponds to /kʰ/ in western and central dialects

- ^ According to some linguists, Ukrainian may have a pharyngeal [ʕ][11] (when devoiced, [ħ] or sometimes [x] in weak positions).[11] According to others, it is glottal [ɦ].[12][13][14]

- ^ Gheada

- ^ a b Borrowed from Arabic and Hebrew

- ^ It's unclear if [h] is a separate phoneme from [ʜ] or if it's just an allophone of it. The voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ] is a word-final allophone of /ʜ/

- ^ Varies between glottal ([h]) and pharyngeal realizations and is sometimes difficult to distinguish from /x/

- ^ Word-final realisation of /r/

- ^ Sometimes silent, but contrasts with a glottal stop onset in vowel-initial words within a phrase. Its phonemic status is not clear. It has an "extremely limited distribution", linking noun phrases (/ʔiki/ 'small', /ʔana ʕiki/ 'small child') and clauses (/ʕaa/ 'and', /ʕoo/ 'also')

- ^ In free variation with [h]

- ^ Has also been described as uvular [ʁ] or glottal [ɦ]

- ^ Typically heard when in between vowels, or as an allophone of /ɡ/ when in intervocalic position

- ^ Only occurs when following /l/ or /r/ and preceding /a/, and it can be analyzed as an allophone of the glottal stop /ʔ/

- ^ In free variation with [ʁ]

- ^ a b In the Morley dialect

The fricatives and trills (the pharyngeal and epiglottal fricatives) are frequently conflated with pharyngeal fricatives in literature. That was the case for Dahalo and Northern Haida, for example, and it is likely to be true for many other languages. The distinction between these sounds was recognized by IPA only in 1989, and it was little investigated until the 1990s.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Karaoui, Fazia; Djeradi, Amar; Laprie, Yves (November 13, 2021). "The Articulatory and acoustics Effects of Pharyngeal Consonants on Adjacent Vowels in Arabic Language". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Natural Language and Speech Processing (ICNLSP 2021): 7 – via ACLAnthology.

- ^ Polinsky, Maria (2020). The Oxford handbook of languages of the Caucasus. Oxford handbooks. New York: Oxford university press. ISBN 978-0-19-069069-4.

- ^ Kodzasov, S. V. Pharyngeal Features in the Daghestan Languages. Proceedings of the Eleventh International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (Tallinn, Estonia, Aug 1-7 1987), pp. 142-144.

- ^ "Haida Words". www.native-languages.org. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Edmondson, Jerold A.; Esling, John H.; Harris, Jimmy G. Supraglottal cavity shape, linguistic register, and other phonetic features of Somali (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ John Esling (2010) "Phonetic Notation", in Hardcastle, Laver & Gibbon (eds) The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences, 2nd ed., p 695.

The reference "Esling, 1999" is to "The iPA categories 'pharyngeal' and 'epiglottal': laryngoscopic observations of the pharyngeal articulations and larynx height." Language and Speech, 42, 349–372. - ^ a b Edmondson, Jerold A., John H. Esling, Jimmy G. Harris, & Huang Tung-chiou (n.d.) "A laryngoscopic study of glottal and epiglottal/pharyngeal stop and continuant articulations in Amis—an Austronesian language of Taiwan" Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nevin, Bruce (1998). Aspects of Pit River Phonology (PDF) (Ph.D.). The University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Video clips". Archived from the original on September 2, 2007. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ Kossmann, Maarten (March 29, 2017), "Berber-Arabic Language Contact", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.232, ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5, retrieved May 30, 2023

- ^ a b Danyenko & Vakulenko (1995:12)

- ^ Pugh & Press (2005:23)

- ^ The sound is described as "laryngeal fricative consonant" (гортанний щілинний приголосний) in the official orthography: '§ 14. Letter H' in Український правопис, Kyiv: Naukova dumka, 2012, p. 19 (see e-text)

- ^ Українська мова: енциклопедія, Kyiv, 2000, p. 85.

Sources

edit- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- Maddieson, I., & Wright, R. (1995). The vowels and consonants of Amis: A preliminary phonetic report. In I. Maddieson (Ed.), UCLA working papers in phonetics: Fieldwork studies of targeted languages III (No. 91, pp. 45–66). Los Angeles: The UCLA Phonetics Laboratory Group. (in pdf)