The epidemiology of hepatitis D occurs worldwide.[1] Although the figures are disputed, a recent systematic review suggests that up to 60 million individuals could be infected.[2] The major victims are the carriers of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), who become superinfected by the HDV, and intravenous drug users who are the group at highest risk. The infection usually results in liver damage (hepatitis D); this is most often a chronic and severe hepatitis rapidly conducive to cirrhosis.[1]

Detection

editInfection with the HDV is recognized by the finding of the homologous antibody (anti-HD) in serum. Testing for the viral genome (HDV RNA) is limited. In 2013, the 1st World Health Organization International Standard of HDV RNA for nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAT)-based assays was developed.[3]

The underlying HBV infection required to support the HDV is critical to determine the outcome of hepatitis D.[4] In simultaneous coinfection with the HBV, the HDV is rescued by the partner HBV with which it shares the HBsAg coat; in superinfections of HBsAg carriers, it is rescued by the foreign HBV of the carrier which provides the HBsAg coat for the assembly of the HD virion. Coinfections run an acute course; expression of the HDV is accompanied by a weak and transient antibody response and is ephemeral.

In superinfections, the chronic HBV infection and HBsAg state indefinitely sustains the replication of the HDV, resulting in a persistent anti-HD response that can be detected in any random blood sample over time; therefore, carriers of the HBsAg are the only reliable source of epidemiological information. However, HDV infections are highly pathogenic and induce the development of liver cirrhosis in approximately 70% of cases within five to ten years, with the risk of cirrhosis threefold higher in HDV-HBV co-infected than in HBV mono-infected patients.[5] As the probability of finding anti-HD throughout the clinical spectrum of HBV liver disorders increases in parallel with the severity of the liver disease. Patients with advanced HBV liver disease are the most suitable category of HBV carriers to determine the epidemiology and real health burden of HDV.

By region

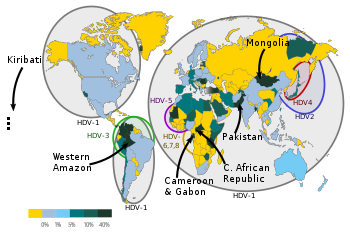

editLow HDV endemicity areas are North America, North Europe and Australia, where it is virtually confined to intravenous drug users and immigrants from infected areas.[6] High endemicity areas remain in the Amazon basin and low income regions of Asia and Africa; outbreaks and fulminant hepatitis D were reported in the past in the Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon, the Central African Republic, the Himalayan foothills[1] and after the year 2000, in Samara (Russia), Greenland and Mongolia.[6]

By controlling HBV infection, the implementation of hepatitis B vaccination in the industrialized world has led to a marked reduction of HDV[6] particularly in Southern Europe and Taiwan. In Italy, HDV diminished among HBV liver disorders from 24.6% in 1983 to 8% in 1997. The residual prevalence of chronic hepatitis D in HBV liver diseases in Western Europe is, as of 2010, between 4.5% and 10%, with immigrants from endemic HDV areas accounting for the larger proportion of cases.[7]

The risk of HDV has not significantly changed in recent years in countries of the world where HBV remains uncontrolled. In Asia up to 2015, the highest prevalences of chronic HDV liver disease were reported in Pakistan, Iran, Tajikistan, and Mongolia;[8][9] a 2019 study has shown that over 80% of HBsAg cirrhosis cases in Uzbekistan are associated with HDV infection.[10] From partial and scattered information the prevalence in China,[11] and India[12] appears to be low.

In many countries of Africa, the role of hepatitis D is unknown for lack of testing. The highest rates of HDV infection were reported in sub-Saharan Africa,[13][14] with the finding of anti-HD in over 30% and 50% of the general HBsAg population of Gabon and Cameroon, respectively, and in over 50% of the HBsAg cirrhotics in the Central African Republic (Figure 1). Lesser but consistent antibody rates (from 20% to 43%, with a mean of 24%) were reported in HBsAg liver disease in Tunisia, Mauritania, Senegal, Nigeria, Somalia and upper Egypt.[15][16][17][18] Low prevalences of 2.5% and 12.7% have been reported in HBV disease carriers in Libya and Ethiopia.[19][20][21][22]

Low prevalence of 0 to 8% has also been reported from Morocco, Algeria, Burkina-Faso, Benin, Mali, Sudan, South Africa and Mozambique; however, they were derived from asymptomatic HBsAg-carriers at low risk of HDV, collected at blood banks and in pregnancy clinics.[23]

References

editThis article was adapted from the following source under a CC BY 4.0 license (2020) (reviewer reports): Mario Rizzetto (31 March 2020). "Epidemiology of the Hepatitis D virus" (PDF). WikiJournal of Medicine. 7 (1): 1. doi:10.15347/WJM/2020.001.2. ISSN 2002-4436. Wikidata Q89093122.

- ^ a b c Smedile, A; Rizzetto, M; Gerin, J (February 1994). "Advances in hepatitis D virus biology and disease". Progress in Liver Diseases. 12: 157–175. ISSN 1060-913X. OCLC 1587746. PMID 7746872.

- ^ Stockdale, Alexander J; Kreuels, Benno; Henrion, Marc R Y; Giorgi, Emanuele; Kyomuhangi, Irene; Geretti, Anna Maria (2020). "Hepatitis D prevalence: problems with extrapolation to global population estimates" (PDF). Gut. 69 (2): 396–397. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317874. ISSN 0017-5749. PMID 30567743. S2CID 58554052.

- ^ Chudy, Michael; Hanschmann, Kay-Martin; Bozdayi, Mithat; Kreß, Julia; Nübling, C. Micha (October 2013). "Collaborative Study to Establish a World Health Organization International Standard for Hepatitis D Virus RNA for Nucleic Acid Amplification Technique (NAT)-Based Assays" (PDF). who.int. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Farci, Patrizia (2003). "Delta hepatitis: An update". Journal of Hepatology. 39: 212–219. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(03)00331-3. PMID 14708706.

- ^ Fattovich, G.; Giustina, G.; Christensen, E.; Pantalena, M.; Zagni, I.; Realdi, G.; Schalm, S. W. (2000). "Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B". Gut. 46 (3): 420–426. doi:10.1136/gut.46.3.420. PMC 1727859. PMID 10673308.

- ^ a b c Rizzetto, Mario; Ciancio, Alessia (August 2012). "Epidemiology of Hepatitis D". Seminars in Liver Disease. 32 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1323626. ISSN 0272-8087. PMID 22932969. S2CID 23770062.

- ^ Wedemeyer, Heiner; Manns, Michael P. (2010). "Epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of hepatitis D: Update and challenges ahead". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2009.205. PMID 20051970. S2CID 12398362.

- ^ Abbas, Zaigham (2010). "Hepatitis D: Scenario in the Asia-Pacific region". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 16 (5): 554–62. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.554. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 2816266. PMID 20128022.

- ^ Alfaiate, Dulce; Dény, Paul; Durantel, David (2015). "Hepatitis delta virus: From biological and medical aspects to current and investigational therapeutic options". Antiviral Research. 122: 112–129. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.08.009. ISSN 0166-3542. PMID 26275800.

- ^ Khodjaeva, Malika; Ibadullaeva, Nargiz; Khikmatullaeva, Aziza; Joldasova, Elizaveta; Ismoilov, Umed; Colombo, Massimo; Caviglia, Gian Paolo; Rizzetto, Mario; Musabaev, Erkin (2019). "The medical impact of hepatitis D virus infection in Uzbekistan". Liver International. 39 (11): 2077–2081. doi:10.1111/liv.14243. PMID 31505080. S2CID 202554415.

- ^ Chen HY, Shen DT, Ji DZ, Han PC, Zhang WM, Ma JF, Chen WS, Goyal H, Pan S, Xu HG (March 2019). "Prevalence and burden of hepatitis D virus infection in the global population: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Gut. 68 (3): 512–521. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316601. PMID 30228220. S2CID 206969154.

- ^ Jat SL, Gupta N, Kumar T, Mishra S, S A, Yadav V, Goel A, Aggarwal R (March 2015). "Prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection among hepatitis B virus-infected individuals in India". Indian J Gastroenterol. 34 (2): 164–8. doi:10.1007/s12664-015-0555-6. PMID 25902955. S2CID 20904078.

- ^ Rizzetto, Mario (2019). "Hepatitis D Virus". In Wong, Robert J.; Gish, Robert G. (eds.). Clinical Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Diseases. pp. 135–148. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94355-8_11. ISBN 978-3-319-94355-8. S2CID 239936838.

- ^ Stockdale, Alexander J.; Chaponda, Mas; Beloukas, Apostolos; Phillips, Richard Odame; Matthews, Philippa C.; Papadimitropoulos, Athanasios; King, Simon; Bonnett, Laura; Geretti, Anna Maria (2017). "Prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Global Health. 5 (10): e992 – e1003. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30298-X. PMC 5599428. PMID 28911765.

- ^ Yacoubi L, Brichler S, Mansour W, Le Gal F, Hammami W, Sadraoui A, Ben Mami N, Msaddek A, Cheikh I, Triki H, Gordien E (November 2015). "Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B and Delta virus strains that spread in the Mediterranean North East Coast of Tunisia". J. Clin. Virol. 72: 126–32. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2015.10.002. PMID 26513762.

- ^ Opaleye OO, Japhet OM, Adewumi OM, Omoruyi EC, Akanbi OA, Oluremi AS, Wang B, van Tong H, Velavan TP, Bock CT (April 2016). "Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis D virus circulating in Southwestern Nigeria". Virol. J. 13: 61. doi:10.1186/s12985-016-0514-6. PMC 4820959. PMID 27044424.

- ^ Hassan-Kadle MA, Osman MS, Ogurtsov PP (September 2018). "Epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Somalia: Systematic review and meta-analysis study". World J. Gastroenterol. 24 (34): 3927–3957. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i34.3927. PMC 6141335. PMID 30228786.

- ^ Saudy N, Sugauchi F, Tanaka Y, Suzuki S, Aal AA, Zaid MA, Agha S, Mizokami M (August 2003). "Genotypes and phylogenetic characterization of hepatitis B and delta viruses in Egypt". J. Med. Virol. 70 (4): 529–36. doi:10.1002/jmv.10427. PMID 12794714. S2CID 24724734.

- ^ Elzouki AN, Bashir SM, Elahmer O, Elzouki I, Alkhattali F (December 2017). "Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis D virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection attending the three main tertiary hospitals in Libya". Arab J Gastroenterol. 18 (4): 216–219. doi:10.1016/j.ajg.2017.11.003. PMID 29241726.

- ^ Spertilli Raffaelli C, Rossetti B, Zammarchi L, Redi D, Rinaldi F, De Luca A, Montagnani F (September 2018). "Multiple chronic parasitic infections in an immunocompetent immigrant: a challenge for healthcare management". Infez Med. 26 (3): 276–279. PMID 30246773.

- ^ Aberra H, Gordien E, Desalegn H, Berhe N, Medhin G, Mekasha B, Gundersen SG, Gerber A, Stene-Johansen K, Øverbø J, Johannessen A (June 2018). "Hepatitis delta virus infection in a large cohort of chronic hepatitis B patients in Ethiopia". Liver Int. 38 (6): 1000–1009. doi:10.1111/liv.13607. PMID 28980394. S2CID 24848759.

- ^ Belyhun Y, Liebert UG, Maier M (September 2017). "Clade homogeneity and low rate of delta virus despite hyperendemicity of hepatitis B virus in Ethiopia". Virol. J. 14 (1): 176. doi:10.1186/s12985-017-0844-z. PMC 5596854. PMID 28899424.

- ^ Andersson MI, Maponga TG, Ijaz S, Barnes J, Theron GB, Meredith SA, Preiser W, Tedder RS (November 2013). "The epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected pregnant women in the Western Cape, South Africa". Vaccine. 31 (47): 5579–84. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.028. PMC 3898695. PMID 23973500.