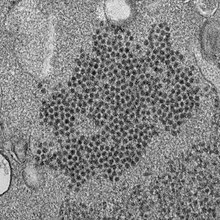

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) is a member of the Picornaviridae family, an enterovirus. First isolated in California in 1962 and once considered rare, it has been on a worldwide upswing in the 21st century.[2][3][4] It is suspected of causing a polio-like disorder called acute flaccid myelitis (AFM).

| Enterovirus D68 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Enterovirus D68 | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Picornaviridae |

| Genus: | Enterovirus |

| Species: | |

| Serotype: | Enterovirus D68

|

| Synonyms | |

| |

Virology

editEV-D68 is one of the more than one hundred types of enteroviruses, a group of ssRNA viruses containing the polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, and echoviruses. It is unenveloped. Unlike all other enteroviruses, EV-D68 displays acid lability and a lower optimum growth temperature, both characteristic features of the human rhinoviruses. It was previously called human rhinovirus 87 by some researchers.[5]

Since the year 2000, the original virus strains diversified and evolved a genetically distinct outbreak strain, clade B1. It is Clade B1, but not older strains, which has been associated with AFM and is neuropathic in animal models.[6]

Epidemiology

editSince its discovery in 1962, EV-D68 had been described mostly sporadically in isolated cases. Six clusters (10 or more cases) or outbreaks between 2005 and 2011 have been reported from the Philippines, Japan, the Netherlands, and the states of Georgia, Pennsylvania and Arizona in the United States.[7] EV-D68 was found in 2 of 5 children during a 2012/13 cluster of polio-like disease in California.[8] In 2016, 29 cases were reported in Europe (5 in France and Scotland. 3 each in Sweden, Norway and Spain).[9]

Cases have been described to occur late in the enterovirus season (roughly the period of time between the spring equinox and autumn equinox),[7] which is typically during August and September in the Northern Hemisphere.

Predisposing factors

editChildren less than 5 years old and children with asthma appear to be most at risk for the illness,[10] although illness in adults with asthma and immunosuppression have also been reported.[7]

2014 North American outbreak

editIn August 2014, the virus caused clusters of respiratory disease in the United States,[11] resulting in the largest documented outbreak of EV-D68[12] with 2,287 confirmed cases and 14 deaths among children.[13]

Signs and symptoms

editEV-D68 almost exclusively causes respiratory illness, which varies from mild to severe, but can cause a range of symptoms, from none at all, to subtle flu-like symptoms, to debilitating respiratory illness and a suspected rare involvement in a syndrome with polio-like symptoms. Like all enteroviruses, it can cause variable rashes, abdominal pain and soft stools. Initial symptoms are similar to those for the common cold, including a runny nose, sore throat, cough, and fever.[14] As the disease progresses, more serious symptoms may occur, including difficulty breathing as in pneumonia, reduced alertness, a reduction in urine production, and dehydration, and may lead to respiratory failure.[7][14]

The degree of severity of symptoms experienced seems to depend on the demographic population in question. Experts estimate that the majority of the population has, in fact, been exposed to the enterovirus, but that no symptoms are exhibited in healthy adults. In contrast, EV-D68 is disproportionately debilitating in very young children, as well as the very weak. While several hundred people (472), mostly youth, have been exposed to the disease, less than a hundred of those patients have been diagnosed with severe symptoms (such as paralysis), and during the recent outbreak in the US just a single death was recorded over the last weekend of September 2014. The death was of a 10-year-old girl in New Hampshire.[15]

Acute flaccid myelitis

editThe virus is one cause of acute flaccid myelitis, a rare muscle weakness, usually due to polio. In 2014, the cases of two California children were described who tested positive for the virus and had paralysis of one or more limbs reaching peak severity within 48 hours of onset. "Recovery of motor function was poor at 6-month follow-up."[16] As of October 2014, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was investigating 10 cases of paralysis and/or cranial dysfunction in Colorado and other reports around the country, coinciding with the increase in enterovirus D68 activity.[17] As of October 2014 it was believed that the actual number of cases might be 100 or more.[18][19] As of 2018 the link of EV-D68 and the paralysis is strong, meeting six Bradford Hill criteria fully and two partially.[6][20] The CDC recently issued a statement on 17 October 2018 claiming "Right now, we know that poliovirus is not the cause of these AFM cases. CDC has tested every stool specimen from the AFM patients, none of the specimens have tested positive for the poliovirus."[21] In 2019, the CDC has published that AFM is caused by Enterovirus D68.[22]

Diagnosis

editIn 2014, a real-time PCR test to speed up detection was developed by CDC.[23]

Treatment

editThere is no specific treatment and no vaccine, so the illness has to run its course; treatment is directed against symptoms (symptomatic treatment). Most people recover completely; however, some need to be hospitalized, and some have died as a result of the virus.[7] Five EV-D68 paralysis cases were unsuccessfully treated with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin and/or plasma exchange. The treatment had no apparent benefit as no recovery of motor function was seen.[16] A 2015 study suggested the antiviral drug pleconaril may be useful for the treatment of EV-D68.[24]

Prevention

editThe CDC recommend "avoiding those who are sick". Since the virus is spread through saliva and phlegm as well as stool, washing hands is important.[14] Sick people can attempt to decrease spreading the virus by basic sanitary measures, such as covering the nose and mouth when sneezing or coughing.[10] Other measures including cleaning surfaces and toys.[14]

For hospitalized patients with EV-D68 infection, the CDC recommends transmission-based precautions, i.e. standard precautions, contact precautions, as is recommended for all enteroviruses,[25] and to consider droplet precautions.[26]

Environmental cleaning

editAccording to the CDC in 2003, surfaces in healthcare settings should be cleaned with a hospital-grade disinfectant with an EPA label claim for non-enveloped viruses (e.g. norovirus, poliovirus, rhinovirus).[27]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Ishiko, H.; Miura, R.; Shimada, Y.; Hayashi, A.; Nakajima, H.; Yamazaki, S.; Takeda, N. (2002). "Human Rhinovirus 87 Identified as Human Enterovirus 68 by VP4-Based Molecular Diagnosis". Intervirology. 45 (3): 136–41. doi:10.1159/000065866. PMID 12403917. S2CID 29128353.

- ^ Oberste, M. S. (2004). "Enterovirus 68 is associated with respiratory illness and shares biological features with both the enteroviruses and the rhinoviruses". Journal of General Virology. 85 (9): 2577–2584. doi:10.1099/vir.0.79925-0. PMID 15302951.

- ^ Lauinger, I. L.; Bible, J. M.; Halligan, E. P.; Aarons, E. J.; MacMahon, E.; Tong, C. Y. W. (2012). "Lineages, Sub-Lineages and Variants of Enterovirus 68 in Recent Outbreaks". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e36005. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736005L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036005. PMC 3335014. PMID 22536453.

- ^ Tokarz, R.; Firth, C.; Madhi, S. A.; Howie, S. R. C.; Wu, W.; Sall, A. A.; Haq, S.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W. I. (2012). "Worldwide emergence of multiple clades of enterovirus 68". Journal of General Virology. 93 (Pt 9): 1952–1958. doi:10.1099/vir.0.043935-0. PMC 3542132. PMID 22694903.

- ^ Blomqvist, S.; Savolainen, C.; Raman, L.; Roivainen, M.; Hovi, T. (2002). "Human Rhinovirus 87 and Enterovirus 68 Represent a Unique Serotype with Rhinovirus and Enterovirus Features". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (11): 4218–23. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.11.4218-4223.2002. PMC 139630. PMID 12409401.

- ^ a b Dyda, Amalie; Stelzer-Braid, Sacha; Adam, Dillon; Chughtai, Abrar A; MacIntyre, C Raina (2018). "The association between acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) and Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) – what is the evidence for causation?". Eurosurveillance. 23 (3). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.3.17-00310. PMC 5792700. PMID 29386095.

- ^ a b c d e "Clusters of Acute Respiratory Illness Associated with Human Enterovirus 68 — Asia, Europe, and United States, 2008–2010". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 60(38): CDC. 30 September 2011. pp. 1301–1304. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Brown, Eryn (23 February 2014). "Mysterious polio-like illnesses reported in some California children". LA Times. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Knoester, Marjolein (September 2018). "Twenty-Nine Cases of Enterovirus-D68 Associated Acute Flaccid Myelitis in Europe 2016; A Case Series and Epidemiologic Overview". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 38 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002188. PMC 6296836. PMID 30234793.

- ^ a b Gillian Mohney (6 September 2014). "Respiratory Virus Sickening Children in Colorado". ABC News.

- ^ "Severe Respiratory Illness Associated with Enterovirus D68 — Missouri and Illinois, 2014". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 63(Early Release). CDC: 1–2. 8 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Grizer, Cassandra S.; Messacar, Kevin; Mattapallil, Joseph J. (15 February 2024). "Enterovirus-D68 – a reemerging non-polio enterovirus that causes severe respiratory and neurological disease in children". Frontiers in Virology. 4. doi:10.3389/fviro.2024.1328457. ISSN 2673-818X. PMC 11378966. PMID 39246649.

- ^ Shi, Yingying; Ran, Qinqin; Wang, Xiaochen; Shi, Lu (2023). "Seroprevalence of Enterovirus D68 Infection among Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Intervirology. 66 (1): 111–121. doi:10.1159/000531853. ISSN 1423-0100. PMC 10614446. PMID 37793363.

- ^ a b c d "Enterovirus D68: 3 confirmed cases in B.C.'s Lower Mainland". CBC News. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "Rhode Island Child Dies From Complications Of Enterovirus That Has Been Affecting Kids Nationwide". CBS Connecticut. 1 October 2014.

- ^ a b Alexandra Roux; Sabeen Lulu; Emmanuelle Waubant; Carol Glaser; Keith Van Haren (29 April 2014). "A Polio-Like Syndrome in California: Clinical, Radiologic, and Serologic Evaluation of Five Children Identified by a Statewide Laboratory over a Twelve-Months Period". Poster Session III: Child Neurology and Developmental Neurology III. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "CDC continues investigation of neurologic illness; will issue guidelines". AAP News. The American Academy of Pediatrics. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Dan Hurley (24 October 2014). "The mysterious polio-like disease affecting American kids". The Atlantic.

- ^ Hurley, Dan (2014). "Cases of Acute Flaccid Myelitis in Children Suspected in Multiple States, Prompting Comparisons to Polio". Neurology Today. 14 (21): 1. doi:10.1097/01.NT.0000457136.07281.dd.

- ^ Peter Dockrill. We May Finally Know The Cause of Polio-Like Illness Paralysing Children Around The World 23 January 2018, Sciencealert

- ^ "Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: Update on Acute Flaccid Myelitis (AFM) in the U.S. | CDC Online Newsroom | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Notes from the Field: Six Cases of Acute Flaccid Myelitis in Children — Minnesota, 2018". CDC. CDC. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "real-time PCR test to speed up EV-D68 detection". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Liu, Y; Sheng, J; Fokine, A; Meng, G; Shin, W.-H; Long, F; Kuhn, R. J; Kihara, D; Rossmann, M. G (2015). "Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children". Science. 347 (6217): 71–4. Bibcode:2015Sci...347...71L. doi:10.1126/science.1261962. PMC 4307789. PMID 25554786.

- ^ Siegel JD; Rhinehart E; Jackson M; Chiarello L & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (December 2007). "2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings". Am J Infect Control. 35 (10 Suppl 2): S65-164. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. PMC 7119119. PMID 18068815.

- ^ "Severe Respiratory Illness Associated with Enterovirus D68 – Multiple States, 2014". CDCHAN-00369. CDC-Health Alert Network. 12 September 2014. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ CDC (2003). "Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities" (PDF). Retrieved 17 September 2014.

External links

edit- Enterovirus Portal – Enterovirus portal at the Virus Pathogen Resource (ViPR)

- "Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) Resources". Non-polio Enteroviruses, CDC.

- "What is the relationship between EVD68 and acute flaccid myelitis?". YouTube. SRNA. 6 November 2018.