Empire of the Sun is a 1987 American epic coming-of-age war film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Tom Stoppard, based on J. G. Ballard's semi-autobiographical 1984 novel of the same name. The film tells the story of Jamie "Jim" Graham (Christian Bale), a young boy who goes from living with his wealthy British family in Shanghai to becoming a prisoner of war in an internment camp operated by the Japanese during World War II.

| Empire of the Sun | |

|---|---|

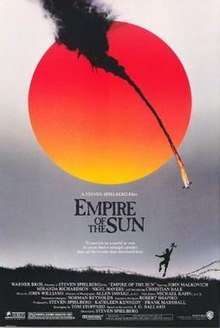

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Tom Stoppard |

| Based on | Empire of the Sun by J. G. Ballard |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Allen Daviau |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 154 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $25 million[1] |

| Box office | $66.7 million[2] |

Harold Becker and David Lean were originally to direct before Spielberg came on board, initially as a producer for Lean.[3] Spielberg was attracted to directing the film because of a personal connection to Lean's films and World War II topics. He considers it to be his most profound work on "the loss of innocence".[1] The film received positive reviews, with praise towards Bale's performance, the cinematography, the visuals, Williams's score and Spielberg's direction. However, the film was not initially a commercial success, earning only $22 million at the US box office, although it eventually more than recouped its budget through revenues in foreign markets, home video, and television.[4]

Plot

editAmid Japan's invasion of China during World War II, Jamie "Jim" Graham is a British upper middle class schoolboy enjoying a privileged life in the Shanghai International Settlement. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan begins occupying the settlement. As the Graham family evacuate the city, Jamie is separated from his parents and makes his way back to their house, assuming they will return. After a length of time alone and having eaten the remaining food, he ventures back into the city.

Hungry, Jamie tries surrendering to Japanese soldiers, who ignore him. After being chased by a street urchin, he is taken in by two American expatriates and hustlers, Basie and Frank. Unable to sell Jamie, they intend to abandon him in the streets, but he offers to lead them to his neighbourhood to loot the empty houses there. He is surprised to see lights on in his family home and thinks his parents have returned, only to discover that the house is occupied by Japanese troops. The trio are taken prisoner, transported to the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Centre in Shanghai for processing, and sent to an internment camp in Suzhou.

Now, in 1945, nearing the end of the Pacific War and World War II. Despite the terror and poor living conditions of the camp, Jim survives by establishing a trading network—which even involves the camp's commander, Sergeant Nagata. Dr. Rawlins, the camp's British doctor, becomes a father figure and teacher to Jim. One night after a bombing raid, Nagata orders the destruction of the prisoners' infirmary as a reprisal but stops when Jim begs forgiveness. Through the barbed wire fencing, Jim befriends a Japanese teenager who is a trainee pilot.

One morning, the base is attacked by American P-51 Mustang fighter aircraft. Jim is overjoyed and climbs the ruins of a nearby pagoda to better watch the action. Dr. Rawlins chases him up the pagoda to save him, whereupon Jim breaks down in tears—saying he cannot remember what his parents look like. As a result of the attack, the Japanese evacuate the camp. As they leave, Jim's trainee pilot friend goes through the ritual kamikaze preparation and attempts to take off in a Japanese attack plane. The trainee is devastated when the engine sputters and dies.

The camp prisoners march through the wilderness, where many die from fatigue, starvation, and disease. Arriving at a football stadium near Nantao, where many of the Shanghai inhabitants' possessions have been stored by the Japanese, Jim recognises his parents' Packard car. He spends the night there with Mrs. Victor, a fellow prisoner who dies shortly thereafter, and witnesses flashes from the atomic bombing of Nagasaki hundreds of miles away.

Jim wanders back to the Suzhou camp. Along the way, he hears news of Japan's surrender and the war's end. He is reunited with the now-disillusioned Japanese teenage pilot, who remembers Jim and offers him a mango, drawing his guntō to cut it. Basie appears with a group of armed Americans to loot the Red Cross containers being airdropped over the area. One of the Americans, thinking Jim is in danger, shoots and kills the Japanese youth. Basie offers Jim to come along with them, but he chooses to stay behind.

He is later found by American soldiers and placed in an orphanage, where he is reunited with his mother and father, though he does not recognise them at first.

Cast

edit- Christian Bale as James "Jim" Graham also known as Jamie

- John Malkovich as Basie

- Miranda Richardson as Mrs. Victor

- Nigel Havers as Dr. Rawlins

- Joe Pantoliano as Frank Demarest

- Leslie Phillips as Maxton

- Masatō Ibu as Sergeant Nagata (Japanese: 永田軍曹, Nagata Gunsō)

- Emily Richard as Mary Graham, Jim's Mother

- Rupert Frazer as John Graham, Jim's Father

- Peter Gale as Mr. Victor

- Takatarō Kataoka as Kamikaze Boy Pilot

- Ben Stiller as Dainty

- Robert Stephens as Mr. Lockwood

- Guts Ishimatsu as Sergeant Uchida (Japanese: 内田軍曹, Uchida Gunsō)

- Burt Kwouk as Mr. Chen

- Paul McGann as Lieutenant Price

- Marc de Jonge as Mathieu

- Eric Flynn as British Prisoner #1

- James Greene as British Prisoner #2

- Paula Hamilton as British Prisoner #3

- Tony Boncza as British Prisoner #4

- Peter Copley as British Prisoner #5

Author J. G. Ballard makes a cameo appearance as a house party guest.

Production

editDevelopment

editWarner Bros. purchased the film rights, intending Harold Becker to direct and Robert Shapiro to produce.[5] Tom Stoppard wrote the first draft of the screenplay, on which Ballard briefly collaborated.[2] Becker dropped out, and David Lean came to direct with Spielberg as producer. Lean explained, "I worked on it for about a year and in the end I gave it up because I thought it was too similar to a diary. It was well-written and interesting, but I gave it to Steve."[5] Spielberg felt "from the moment I read J. G. Ballard's novel I secretly wanted to direct myself."[5] Spielberg found the project to be very personal. As a child, his favourite film was Lean's The Bridge on the River Kwai, which similarly takes place in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Spielberg's fascination with World War II and the aircraft of that era was stimulated by his father's stories of his experience as a radio operator on North American B-25 Mitchell bombers in the China-Burma Theater.[5] Spielberg hired Menno Meyjes to do an uncredited re-write before Stoppard was brought back to write the shooting script.[2]

Casting

editJ.G. Ballard felt Bale had a physical resemblance to himself at the same age.[6] The actor was 12 years old when he was cast. Amy Irving, Bale's co-star in the television movie Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna, recommended Bale to her then-husband, Steven Spielberg, for the role. More than 4,000 child actors auditioned.[7] Jim's singing voice was provided by English performer James Rainbird.[8]

Filming

editEmpire of the Sun was filmed at Elstree Studios in the United Kingdom, and on location in Shanghai and Spain. Principal photography began on 1 March 1987,[9] and lasted for 16 weeks.[10] The filmmakers searched across Asia in an attempt to find locations that resembled 1941 Shanghai. They entered negotiations with Shanghai Film Studios and China Film Co-Production Corporation in 1985.[11] After a year of negotiations, permission was granted for a three-week shoot in early March 1987. It was the first American film shot in Shanghai since the 1940s.[2] The Chinese authorities allowed the crew to alter signs to traditional Chinese characters, as well as closing down city blocks for filming.[11] Over 5,000 local extras were used, some old enough to remember the Japanese occupation of Shanghai 40 years earlier. Members of the People's Liberation Army played Japanese soldiers.[6] Other locations included Trebujena in Andalusia, Knutsford in Cheshire and Sunningdale in Berkshire.[11] Lean often visited the set during the England shoot.[2]

Spielberg attempted to portray the era accurately, using period vehicles and aircraft. Four Harvard SNJ aircraft were lightly modified in France to resemble Mitsubishi A6M Zero aircraft.[12] Two additional non-flying replicas were used. Three restored P-51D Mustangs, two from 'The Fighter Collection' of England, and one from the 'Old Flying Machine Company', were flown in the film.[12] These P-51s were flown by Ray Hanna (who was featured in the film flying at low-level past the child star with the canopy back, waving), his son Mark and "Hoof" Proudfoot and took over 10 days of filming to complete due to the complexity of the planned aerial sequences, which included the P-51s actually dropping plaster-filled replica 500 lb bombs at low level, with simulated bomb blasts. A number of large scale remote control flying models were also used, including an 18-foot wingspan B-29, but Spielberg felt the results were disappointing, so he extended the film contract with the full-size examples and pilots on set in Trebujena, Spain.[13][14] J.G. Ballard makes a cameo appearance at the costume party scene.[6]

Spielberg had wanted to film in Super Panavision 70 but did not want to work with the old camera equipment that was only available at the time.[15]

Special effects

editIndustrial Light & Magic designed the visual effects sequences with some computer-generated imagery also used for the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Norman Reynolds was hired as the production designer while Vic Armstrong served as the stunt co-ordinator.[14]

Reception

editEmpire of the Sun was given a limited release on 11 December 1987 before being widely released on Christmas Day, 1987. The film earned $22.24 million in North America,[4] and $44.46 million in other countries, accumulating a worldwide total of $66.7 million, earning more than its budget but still considered a box office disappointment by Spielberg.[N 1][2]

Critical response

editReview aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 77% based on reviews from 64 critics, with an average rating of 6.8/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "One of Steven Spielberg's most ambitious efforts of the 1980s, Empire of the Sun remains an under-rated gem in the director's distinguished filmography."[17] Metacritic calculated an average score of 62 out of 100 based on 22 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[18] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[19]

J. G. Ballard gave positive feedback, and was especially impressed with Christian Bale's performance.[6] Critical reaction was not universally affirmative,[5] but Richard Corliss of Time stated that Spielberg "has energized each frame with allusive legerdemain and an intelligent density of images and emotions".[20] Janet Maslin from The New York Times said Spielberg's movie-conscious spirit gave it "a visual splendor, a heroic adventurousness and an immense scope that make it unforgettable".[21] Julie Salamon of The Wall Street Journal wrote that the film was "an edgy, intelligent script by playwright Tom Stoppard, Spielberg has made an extraordinary film out of Mr. Ballard's extraordinary war experience."[22][better source needed] J. Hoberman from The Village Voice decried that the serious subject was undermined by Spielberg's "shamelessly kiddiecentric" approach.[5] Roger Ebert gave a mixed reaction, "Despite the emotional potential in the story, it didn't much move me. Maybe, like the kid, I decided that no world where you can play with airplanes can be all that bad."[23] On his TV show with Gene Siskel, Ebert said that the film "is basically a good idea for a film that never gets off the ground". Siskel added, "I don't know what the film is about. It's so totally confused and taking things from different parts. On one hand, if it wants to say something about a child's-eye view of war, you got a movie made by John Boorman called Hope and Glory that was just released that is much better, and much more daring in showing the whimsy that children's view of war is. On the other hand, this film wants to hedge its bet and make it like an adventure film, so you've got like Indiana Jones with the John Malkovich character helping the little kid through all the fun of war. I don't know what Spielberg wanted to do."[24]

Awards

editThe film won awards from the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures for Best Film and Best Director, and Bale received a special citation for Best Performance by a Juvenile Actor, the first National Board award bestowed on a child actor.[25][26] At the 60th Academy Awards, Empire of the Sun was nominated for Art Direction, Cinematography, Costume Design (Bob Ringwood), Film Editing, Original Music Score, and Sound (Robert Knudson, Don Digirolamo, John Boyd and Tony Dawe). It did not convert any of the nominations into awards.[27] Allen Daviau, who was nominated as cinematographer, publicly complained, "I can't second-guess the Academy, but I feel very sorry that I get nominations and Steven doesn't. It's his vision that makes it all come together, and if Steven wasn't making these films, none of us would be here."[2] The film won awards for cinematography, sound design, and music score at the 42nd British Academy Film Awards. The nominations included production design, costume design, and adapted screenplay.[28] Spielberg was honored for this work by the Directors Guild of America,[29] while the American Society of Cinematographers honored Allen Daviau.[30] Empire of the Sun was nominated for Best Motion Picture (Drama) and Original Score at the 45th Golden Globe Awards.[31] John Williams earned a Grammy Award nomination.[32]

Themes

editJim's growing alienation from his pre-war self and society is reflected in his hero-worship of the Japanese aviators based at the airfield adjoining the camp. "I think it's true that the Japanese were pretty brutal with the Chinese, so I don't have any particularly sentimental view of them," Ballard recalled. "But small boys tend to find their heroes where they can. One thing there was no doubt about, and that was that the Japanese were extremely brave. One had very complicated views about patriotism [and] loyalty to one's own nation. Jim is constantly identifying himself, first with the Japanese; then, when the Americans start flying over in their Mustangs and B-29s, he's very drawn to the American."[5]

The apocalyptic wartime setting and the climactic moment when Jim sees the distant white flash of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki gave Spielberg powerful visual metaphors "to draw a parallel story between the death of this boy's innocence and the death of the innocence of the entire world".[33] Spielberg reflected he "was attracted to the idea that this was a death of innocence, not an attenuation of childhood, which by my own admission and everybody's impression of me is what my life has been. This was the opposite of Peter Pan. This was a boy who had grown up too quickly."[1] Other topics that Spielberg previously dealt with, and are presented in Empire of the Sun, include a child being separated from his parents (The Sugarland Express, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Color Purple, and Poltergeist)[N 2] and World War II (1941, and Raiders of the Lost Ark).[34] Spielberg explained "My parents got a divorce when I was 14, 15. The whole thing about separation is something that runs very deep in anyone exposed to divorce."[1]

In popular culture

editThe dramatic attack on the Japanese prisoner of war camp carried out by P-51 Mustangs is accompanied by Jim's whoops of "...the Cadillac of the skies!", a phrase believed to be first used in Ballard's text as "Cadillac of air combat".[35] Steven Bull quotes the catchwords in the Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation (2004) as originating in 1941.[36] John Williams's soundtrack includes "Cadillac of the Skies" as an individual score cue.

Ben Stiller conceived the idea for Tropic Thunder while performing in Empire of the Sun.[37]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In 1989, Spielberg was quoted as saying: "...Empire of the Sun wasn't a very commercial project, it wasn't going to have a broad audience appeal... I've earned the right to fail commercially."[16]

- ^ Film historian and author Kowalski collectively links these films as Spielberg's "family" or conversely, as his "displaced father" films.[34]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Forsberg, Myra. "Spielberg at 40: The Man and the Child" Archived February 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, October 1, 2008. Retrieved: September 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g McBride 1997, pp. 394–398.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 391.

- ^ a b " Empire of the Sun" Archived May 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Mojo (Amazon.com). Retrieved: September 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g McBride 1997, p. 392.

- ^ a b c d Sheen, Martin (narrator), Steven Spielberg, J.G. Ballard, and Christian Bale. The China Odyssey: Empire of the Sun American Broadcasting Company, 1987.

- ^ Wills, Dominic. "Christian Bale Biography" Archived 2008-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Tiscali. Retrieved: September 16, 2008.

- ^ Bullock, Paul. "Spielberg Questions #4: Did Christian Bale sing in Empire of the Sun?" Archived March 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. From Director Steven Spielberg. Retrieved: March 5th 2016.

- ^ "Empire of the Sun - Miscellaneous Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Yarrow, Andrew (December 16, 1987). "Boy in 'Empire' calls acting 'really good fun'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c Walker 1988, p. 49.

- ^ a b "Mark Hanne 1959-1999". Air Classics. 35 (10). Canoga Park, CA, US: Challenge Publications: 6. November 1999. ISSN 0002-2241. OCLC 733866638. ProQuest 235492832.

- ^ "Empire Of The Sun Exclusive Look At Steven Spielberg's New WWII Movie!". Air Classics. 24 (1). Canoga Park, CA, US: Challenge Publications. January 1988. ISSN 0002-2241. OCLC 637419754.[pages needed]

- ^ a b Walker 1988, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Everett, Todd (May 21, 1992). "Panavision redefines the wide-body look". Daily Variety. p. 17.

- ^ Friedman and Notbohn 2000, p. 137.

- ^ "Empire of the Sun (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "Empire of the Sun Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 7, 1987). "Cinema: The Man-Child Who Fell to Earth EMPIRE OF THE SUN". Time. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Maislin, Janet. "Empire of the Sun" Archived March 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, December 9, 1987. Retrieved: September 16, 2008.

- ^ Salmon, Julie. "Empire of the Sun" Archived October 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Wall Street Journal, December 9, 1987. Retrieved: January 31, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Empire of the Sun". Chicago Sun-Times, December 11, 1987. Retrieved: September 16, 2008. Archived September 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Empire of the Sun". Siskel & Ebert. Disney-ABC Domestic Television. December 12, 1987. Television.

- ^ "'Empire of Sun' said best film by National Board". The San Bernardino County Sun. San Bernardino, CA. AP. February 17, 1988. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "National Board of Review 1987 Award Winners" Archived January 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. National Board of Review. Retrieved: October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 60th Academy Awards" Archived 2010-04-08 at the Wayback Machine Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved: January 31, 2011.

- ^ "42nd British Academy Awards" Archived December 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Retrieved: September 17, 2008.

- ^ "DGA Awards: 1988" Archived January 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Retrieved: September 17, 2008.

- ^ "ASC Awards: 1988" Archived February 25, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Retrieved: September 17, 2008.

- ^ "The 45th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1988)" Archived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Golden Globes. Retrieved: January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Grammy Awards: 1988" Archived August 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Retrieved: September 17, 2008.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 393.

- ^ a b Kowalski 2008, pp. 35, 67.

- ^ Ballard 1984, p. 151.

- ^ Bull 2004, p. 184.

- ^ Vary, Adam B. "First Look: Tropic Thunder" Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly, March 5, 2008. Retrieved: May 27, 2008.

Sources

edit- Ballard, J.G. (2002). Empire of the Sun, first edition. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 0-575-03483-1.

- Bull, Steven (2004). Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- Dolan, Edward F. (1985). Hollywood Goes to War. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Evans, Alun (2000). Brassey's Guide to War Films. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-263-5.

- Friedman, Lester D; Notbohm, Brent (2000). Steven Spielberg: Interviews. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-113-6.

- Gordon, Andrew; Gormile, Frank (2002). The Films of Steven Spielberg. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 109–123, 127–137. ISBN 0-8108-4182-7.

- Hardwick, Jack; Schnepf, Ed (1989). "A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies". The Making of the Great Aviation Films (General Aviation Series, vol. 2).

- Kowalski, Dean A. (2008). Steven Spielberg and Philosophy: We're Gonna Need a Bigger Book. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2527-5.

- McBride, Joseph (1987). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- Walker, Jeff (January 1988). "Empire of the Sun". Air Classics. 24.

External links

edit- Official Website

- Empire of the Sun at IMDb

- Empire of the Sun at the TCM Movie Database

- Empire of the Sun at AllMovie

- Empire of the Sun at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Empire of the Sun at Rotten Tomatoes

- Empire of the Sun at Box Office Mojo

- Empire of the Sun at Metacritic