Emily, also known as The Awakening of Emily, is a 1976 British erotic historical drama film set in the 1920s directed by Henry Herbert, produced and written by Christopher Neame, and starring Koo Stark.[1]

| Emily | |

|---|---|

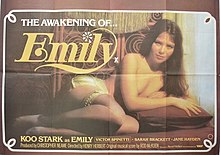

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Henry Herbert |

| Screenplay by | Christopher Neame |

| Produced by | Christopher Neame |

| Starring | Koo Stark Sarah Brackett Victor Spinetti Constantin de Goguel Ina Skriver Richard Oldfield |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | Keith Palmer |

| Music by | Rod McKuen |

Production company | Emily Productions |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

The story revolves around a seventeen-year-old girl who is pursued by various middle aged men and women. The main setting of the film is Wilton House, which was the director's ancestral seat, and the countryside around it.[2]

An X-rated film, it has a cast of mainstream actors including Victor Spinetti, Sarah Brackett, Constantin de Goguel, Ina Skriver, Jeremy Child, Jack Haig, and Richard Oldfield. Its music was composed and sung by the singer and poet Rod McKuen.

Plot

editEmily Foster is an American-born seventeen-year-old brought up in London. Her father died when she was a small child, while her mother, Margaret Foster, is supported by a lover. The film, set in 1928, follows Emily as she returns home from a finishing school in Switzerland to her mother's country house in the English countryside, where she meets several characters who would like to seduce her, and follows her induction into sensual pleasures. The film follows her interactions with these adult pursuers.[3] Richard Walker, her mother's lover, is a middle-aged man-about-town who quietly sets his sights on Emily, while a young American writer and schoolteacher named James Wise tries to impress her by sensual acrobatics in his flying machine. However, her first sexual experience is an encounter with a woman — Augustine Wain, a Swedish painter who lives nearby. Emily then has her first sexual encounter with a man, Wain's husband, the middle aged Rupert Wain in a scene indicating penetrative sex.[4][5]

Meanwhile, perhaps intended to mark the contrast in the sexual mores of the different British classes at the time, housemaid Rachel (Jane Hayden) and her soldier boyfriend Billy (David Auker) are engaged to be married, but Rachel tries to insist on waiting until after their wedding before they have sexual intercourse.[5]

Cast

edit- Koo Stark as Emily Foster

- Sarah Brackett as Margaret Foster

- Victor Spinetti as Richard Walker

- Jane Hayden as Rachel

- Constantin de Goguel as Rupert Wain

- Ina Skriver as Augustine Wain

- Richard Oldfield as James Wise

- David Auker as Billy Edwards

- Jeremy Child as Gerald Andrews

- Jack Haig as taxi driver

- Jeannie Collings as Rosalind

- Pamela Cundell as Mrs Prince

Production

editThe film was produced by Christopher Neame,[6] who also wrote the screenplay, claiming to have completed it in seventeen hours. It was intended as a vehicle for him to move into production, and Emily did indeed become his first film. He secured the services of Henry Herbert as director, together with his large house and estate in Wiltshire as location. Neame later wrote that this was "a country house of faded grandeur, but it suited the narrative well with its plush reds and rich greens, all set in a golden landscape".[2] Neame went on to produce Danger UXB, The Flame Trees of Thika, The Irish R.M., Soldier, Soldier, and Monsignor Quixote.[6]

The director, Henry Herbert, had begun by making documentaries about musicians but was directing only his second feature film.[7] His first had been Malachi's Cove (1974), starring Donald Pleasence, which he had both written and directed, based on a short story by Anthony Trollope.[8][9] The art director of Emily, Jacquemine Charrott Lodwidge, had also worked on Malachi's Cove.[10] The film editor, Keith Palmer, had worked with Lodwidge on another country house picture, Blue Blood (1973), filmed at the nearby Longleat House.[11] The film was Peter Bennett's first as assistant director.[4]

Release

editBox Office

editEmily was a moderate success at the box office in the 1970s, but in the early 1980s it had a revival and did far better, gaining publicity due to a romance between Koo Stark and Prince Andrew.[2] Around that time the film was often shown on HBO and other cable TV channels.[12]

Critical reception

editThe critics did not like the script. Alan Brien wrote in The Observer that Neame and Herbert should have been less tame with a scene in the drawing room, as censorship had been relaxed and the sexuality could have been more explicit. For Kenneth Tynan, Emily "failed to get to first base" in his realm of eroticism.[2]

Variety wrote:

Story set in England in 1928 deals with teenage Emily returning from finishing school and her subsequent sexual awakening. It is sufficiently well told to sustain screen interest throughout although the acting performance of the cast is collectively unimpressive. Director Henry Herbert lacks consistency, but given the modest budget has put a lot on the screen. Rod McKuen's music score is incongruous at times and never outstanding. A first-time effort for producer Christopher Neame (son of Ronald), this Brent Walker release is a classier than normal British-made entry with highly effective camera work by Jack Hildyard. It has good international playoff potential in selected situations with some strong built in exploitation angles, notably topliner Koo Stark, who will look good on posters, front of house stills, etc.[4]

The Motion Picture Guide (1986) commented: "Rod McKuen contributes a typically wretched soundtrack."[13]

In their book Great Houses of England & Wales (1994), Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes later wrote: "The present Lord Pembroke is (as Henry Herbert) a film and television director, best known for the Civil War drama series By the Sword Divided and for Emily, starring Miss Koo Stark."[14]

The historian Simon Sebag Montefiore went to see the film while at school, expecting a skin flick, thanks to sensational press coverage, and later described it as "one of the biggest disappointments of my adolescence".[15]

Certification

editIn 1983, the film was rejected by the British Board of Film Classification because of a scene showing two women embracing in a shower.[16]

Aftermath

editThe film's leading lady, Koo Stark, suffered in later years from press misrepresentation. In a libel action in 2007, she won an apology and substantial damages from Zoo Weekly, which had described her as a porn star. She commented "I am relieved that my name has been cleared of this false, highly damaging and serious allegation."[17] In June 2019 Stark again won damages for libel in an action against Viacom, whose MTV company had referred to her in the same terms.[18]

Notes

edit- ^ "Emily". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Christopher Neame, A Take on British TV Drama: Stories from the Golden Years (Scarecrow Press, 2004), p. xiv-xv

- ^ Jim Craddock, VideoHound's Golden Movie Retriever: 2002 (2001), p. 238

- ^ a b c 'Emily', in Variety's Film Reviews: 1975-1977, volume 14 of series (R. R. Bowker, 1989)

- ^ a b I. Q. Hunter, Cult Film as a Guide to Life: Fandom, Adaptation, and Identity (2016), p. 99

- ^ a b Christopher Neame, Rungs on a Ladder: Hammer Films Seen Through a Soft Gauze (2003), p. 122

- ^ Harris M. Lentz III, ed., Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2003, p. 188

- ^ Denis Gifford, British Film Catalogue: Two Volume Set - The Fiction Film/The Non-Fiction Film

- ^ Films and Filming Volume 20 (1973), p. 6

- ^ Mike Kaplan, Variety international showbusiness reference (1982), p. 388

- ^ Harris M. Lentz, Science Fiction, Horror & Fantasy Film and Television Credits (2001), p. 915

- ^ Arts and Culture, Volume 2 (2016), p. 74

- ^ Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph; Connelly, Robert B. (1986). The Motion Picture Guide. Cinebooks, 1986, Volume 3, p. 760.

- ^ Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh; Sykes, Christopher Simon (1994). Great Houses of England & Wales. p. 131.

- ^ Hardy, Rebecca (2008-10-17). "Homeless and broke - Koo's Stark life". Thurrock Mail, 17 October 2008.

- ^ Ursula Smartt, Media & Entertainment Law (2017), p. 249

- ^ Koo Stark news release at carter-ruck.com, accessed 12 November 2017

- ^ "Prince Andrew’s ex wins damages over ‘porn star’ label", in The Times (London), 10 June 2019, accessed 16 February 2020