This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Heinrich Emil Brunner[b] (1889–1966) was a Swiss Reformed theologian. Along with Karl Barth, he is commonly associated with neo-orthodoxy or the dialectical theology movement.

Emil Brunner | |

|---|---|

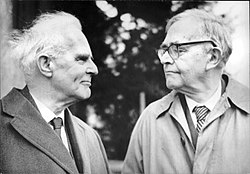

Brunner (left) with Karl Barth | |

| Born | Heinrich Emil Brunner 23 December 1889 Winterthur, Switzerland |

| Died | 6 April 1966 (aged 76) Zürich, Switzerland |

| Spouse |

Margrit Lautenburg (m. 1916) |

| Ecclesiastical career | |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Church | Swiss Reformed Church[2] |

| Ordained | 1912[2] |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Thesis | The Symbolic Element in Religious Knowledge[a] (1913) |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Theology |

| Sub-discipline | Systematic theology |

| School or tradition | Neo-orthodoxy |

| Institutions | University of Zurich |

| Doctoral students | |

Biography

editBrunner was born on 23 December 1889 in Winterthur, in the Swiss canton of Zürich.[9]

He studied at the universities of Zurich and Berlin, receiving his doctorate in theology from Zurich in 1913, with a dissertation on The Symbolic Element in Religious Knowledge.[a] Brunner served as pastor from 1916 to 1924 in the mountain village of Obstalden in the Swiss canton of Glarus. In 1919–1920 he spent a year in the United States studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

In 1921, Brunner published his Habilitationsschrift (a post-doctoral dissertation traditionally required in many countries in order to attain the position of a fully tenured professor) on Experience, Knowledge and Faith and in 1922 was appointed a Privatdozent at the University of Zurich. Soon after, another book followed: Mysticism and the Word (1924), a critique of the liberal theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher. In 1924 Brunner was appointed Professor of Systematic and Practical Theology at the University of Zurich, a post which he held until his retirement in 1953. In 1927 he published The Philosophy of Religion from the Standpoint of Protestant Theology and second The Mediator.

After accepting various invitations to deliver lectures across Europe and the United States, in 1930 Brunner published God and Man and in 1932 The Divine Imperative. Brunner continued his theological output with Man in Revolt and Truth as Encounter in 1937. In the same year, he was a substantial contributor to the World Conference on Church, Community, and State in Oxford, a position which was reflected in his continued involvement in the ecumenical movement.[citation needed] In 1937–1938 he returned to the United States for a year as a visiting professor at Princeton Theological Seminary.[10]

Brunner's ecclesiastical positions varied at differing points in his career. Before the outbreak of the war, Brunner returned to Europe with the young Scottish theologian Thomas F. Torrance who had studied under Karl Barth in Basel and who had been teaching at Auburn Theological Seminary, New York (and who would subsequently go on to distinguish himself as a professor at the University of Edinburgh). Following the war, Brunner delivered the prestigious Gifford Lectures at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, in 1946–1947 on Christianity and Civilisation. In 1953 he retired from his post at the University of Zurich and took up the position of Visiting Professor at the recently founded International Christian University in Tokyo, Japan (1953–1955), but not before the publication of the first two volumes of his three-volume magnum opus Dogmatics (volume one: The Christian Doctrine of God [1946], volume two: The Christian Doctrine of Creation and Redemption [1950], and volume three: The Christian Doctrine of the Church, Faith, and Consummation [1960]). While returning to Europe from Japan, Brunner suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and was physically impaired, weakening his ability to work. Though there were times when his condition would improve, he suffered further strokes, finally dying on 6 April 1966 in Zürich.

Brunner holds a place of prominence in Protestant theology in the 20th century and was one of the four or five leading systematicians.[citation needed]

Theology

editBrunner rejected liberal theology's portrait of Jesus as merely a highly respected human being. Instead, Brunner insisted that Jesus was God incarnate and central to salvation.

Some[who?] claim that Brunner also attempted to find a middle position within the ongoing Arminian and Calvinist debate, stating that Christ stood between God's sovereign approach to mankind and free human acceptance of God's gift of salvation. However, Brunner was a Protestant theologian from German-speaking Europe (a heritage which did not lay nearly as much weight on the Calvinist–Arminian controversy as Dutch- or English-speaking theology). Thus, it may be more accurate to describe his viewpoint as a melding of Lutheran and Reformed perspectives of soteriology; the Lutheran accent, in particular, was dominant in Brunner's affirmation of single predestination over against both the double predestination of Calvin and the liberal insistence on universal salvation, a view he charged Barth with holding.

In any event, Brunner and his compatriots in the neo-orthodox movement rejected in toto Pelagian concepts of human cooperation with God in the act of salvation, which were prominent in other humanist conceptions of Christianity in the late 19th century. Instead, they embraced Augustine of Hippo's views, especially as refracted through Martin Luther.

Although Brunner re-emphasized the centrality of Christ, evangelical and fundamentalist theologians, mainly those from America and Great Britain, have usually rejected Brunner's other teachings, including his dismissal of certain miraculous elements within the scriptures and his questioning of the usefulness of the doctrine of plenary verbal inspiration of the Bible. This is in accord with the treatment that conservatives have afforded others in the movement such as Barth and Paul Tillich; most conservatives have viewed neo-orthodox theology as simply a more moderate form of liberalism, rejecting its claims as a legitimate expression of the Protestant tradition.

Relationship with Karl Barth

editBrunner was considered to be the chief proponent of the new theology long before Barth's name was known in America, as his books had been translated into English much earlier. He has been considered by many to be the minor partner in the uneasy relationship.[citation needed] Brunner once acknowledged that the only theological genius of the 20th century was Barth.[citation needed]

Selected works in English

edit- The Mediator, (translated by Olive Wyon; The Lutterworth Press 1934, reprinted Cambridge 2003)

- Our Faith (1936)

- The Divine Imperative (1st German edition 1932; English translation 1937 and 1941)

- Man in Revolt. A Christian Anthropology (1st German edition 1937; English translation 1939 and 1941)

- Revelation and Reason. The Christian Doctrine of Faith and Knowledge, (1st German edition 1941, English translation 1946)

- Christianity and Civilisation (1949) Gifford Lectures Delivered at the University of St Andrews, James Clarke & Co, reprinted Cambridge 2009

- Dogmatics. Volume I: The Christian Doctrine of God, (1950) reprinted James Clarke & Co, reprinted Cambridge 2003

- Dogmatics. Volume II: The Christian Doctrine of Creation and Redemption, (1952) reprinted James Clarke & Co, Cambridge 2003

- Dogmatics. Volume III: The Christian Doctrine of the Church, Faith and the Consummation, (1950) reprinted James Clarke & Co, Cambridge 2003

- Eternal Hope (1954)

- The Great Invitation Zurich Sermons, (1955) The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge 2003

- I Believe in the Living God. Sermons on the Apostles' Creed, (1961) reprinted The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge 2004

- Justice and Social Order, The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge 2003

- The Letter to the Romans, The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge 2003

- The Misunderstanding of the Church, The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge 2003

Notes

editReferences

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Craver; Schoch 2012.

- ^ a b McGrath 2014, p. 4.

- ^ McGrath 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Livingstone 2013, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Kegley 2005.

- ^ McGrath 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Menacher 2013, p. 312.

- ^ "Brunner". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ McGrath 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Schoch 2012.

Bibliography

edit- Craver, Ben D. "Heinrich Emil Brunner (1889–1966)". In Wildman, Wesley J. (ed.). Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology. Boston: Boston University. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Kegley, Charles W. (2005). "Brunner, Emil". Encyclopedia of Religion. Thomson Gale. Retrieved 19 February 2019 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- Livingstone, E. A., ed. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199659623.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-965962-3.

- McGrath, Alister E. (2014). Emil Brunner: A Reappraisal. Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-56926-9.

- Menacher, Mark D. (2013). "Gerhard Ebeling (1912–2001)". In Mattes, Mark C. (ed.). Twentieth-Century Lutheran Theologians. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 307–334. ISBN 978-3-525-55045-8.

- Schoch, Max (2012). "Brunner, Emil". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in French, German, and Italian). Retrieved 19 February 2019.

Further reading

edit- Bautz, Friedrich Wilhelm (1990) [1975]. "Brunner, Emil". In Bautz, Friedrich Wilhelm (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (in German). Vol. 1. Hamm, North Rhine-Westphalia: Bautz. col. 769–770. ISBN 978-3-88309-013-9. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Humphrey, J. Edward (1976). Emil Brunner. Waco, Texas: Word Books. ISBN 978-0-87680-453-7.

- Jehle, Frank (2006). Emil Brunner: Theologe im 20. Jahrhundert (in German). Zürich: Theologischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-290-17392-0.

- Jewett, Paul King (1961). Emil Brunner: An Introduction to the Man and His Thought. Chicago: InterVarsity Press. OCLC 422230677.

- Kegley, Charles W., ed. (1962). The Theology of Emil Brunner. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 393141.

- Williamson, René de Visme (1976). Politics and Protestant Theology: An Interpretation of Tillich, Barth, Bonhoeffer, and Brunner. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-0193-3.