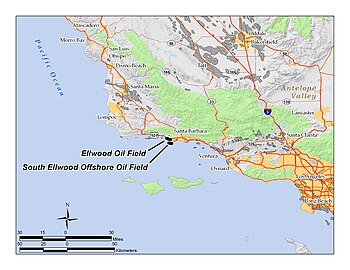

Ellwood Oil Field (also spelled "Elwood")[1] and South Ellwood Offshore Oil Field are a pair of adjacent, partially active oil fields adjoining the city of Goleta, California, about twelve miles (19 km) west of Santa Barbara, largely in the Santa Barbara Channel. A richly productive field in the 1930s, the Ellwood Oil Field was important to the economic development of the Santa Barbara area. A Japanese submarine shelled the area during World War II. It was the first direct naval bombardment of the continental U.S. since the Civil War, causing an invasion scare on the West Coast.

Setting

editThe Ellwood Oil Field is located approximately 12 miles (19 km) west of the city of Santa Barbara, beginning at the western boundary of the city of Goleta, proceeding west into the Pacific and then back onshore near Dos Pueblos Ranch. The onshore portions of the field include beach, coastal bluffs, blufftop grasslands, and eucalyptus groves. Some of the former oil field is now part of the Ellwood-Devereux Open Space, maintained by the city of Goleta, and the Bacara Resort, Sandpiper Golf Course, and new Goleta housing developments sit on areas formerly occupied by pump-jacks, derricks, and oil storage tanks.[2]

The climate is Mediterranean, with an equable temperature regime year-round, and most of the precipitation falling between October and April in the form of rain. Freezes are rare. Runoff is towards the ocean, and to a few vernal pools on the bluffs. The offshore portions of the Ellwood oil field are in relatively shallow water, and were drilled from piers.[3]

The South Ellwood Offshore field is entirely beneath the Pacific Ocean, about two miles (3.2 km) from the main onshore oil field. It is entirely within the State Tidelands zone, which encompasses areas within three nautical miles (5.6 km) of shore. These regions are subject to state, rather than Federal regulation. The last production from this field was from Platform Holly, which is in 211 feet (64 m) of water, about two miles (3.2 km) from the coast at Coal Oil Point and has been shut down.[4] Numerous directionally-drilled oil wells originate at the platform, and several pipelines connect the platform to an onshore oil processing facility adjacent to the Sandpiper Golf Course.[5]

Geology

editThe Ellwood Oil Field is roughly five miles (8.0 km) long and up to a mile wide, with both its eastern and western extremity onshore. It is an anticlinal structure, with oil trapped stratigraphically by the anticline. The More Ranch Fault provides an impermeable barrier on the northeast. Oil occurs in several pools, with the largest being in the Vaqueros Sandstone, approximately 3,400 feet (1,000 m) below ground surface. Other significant pools occur in the Rincon Formation at a depth of 2,600 feet (790 m), and in the Upper Sespe Formation at 3,700 feet (1,100 m) below ground surface.

The Ellwood Oil Field contained approximately 106 million barrels (16,900,000 m3) of oil, almost all of which has been removed, to the degree possible with the technology available until the early 1970s. The field now has been abandoned. The South Ellwood Offshore field has been estimated by the US Department of Energy to hold over one billion barrels of oil[6] and approximately 2.1 billion barrels (330,000,000 m3), most of which is in the undeveloped portion of the field.[7] In 1995, the Oil and Gas Journal reported 155 million barrels (24,600,000 m3) of proven reserves.[8]

Oil from the Ellwood field was generally light and sweet, with an API gravity averaging 38 and low sulfur content (making it "sweet" in petroleum parlance). Oil from the offshore field is medium-grade, ranging from API gravity 25 to 34, and has a higher sulfur content, requiring more processing than the oil from the decommissioned onshore field.

Several pools have been identified in the South Ellwood Offshore field, in three major vertical zones. The upper Monterey Formation contains a large pool in a zone of fractured shale at an average depth of 3,350 feet (1,020 m) below the ocean floor. Beneath that, a separate pool exists in the Rincon Sand, 5,000 feet (1,500 m) below the ocean floor, and yet another in the Vaqueros Formation at a depth of 5,900 feet (1,800 m). The deepest well drilled to date is 6,490 feet (1,980 m) into the Rincon Formation.

History and production

editGoleta Oil Field

editThis was a short-lived oil field which produced for only 13 months before water appeared in the wells. Production ceased by Feb. 1928. Miley Oil Company drilled the No. Goleta 1 discovery well, with oil shows at 613 and 1,527 feet.[9]

Ellwood Oil Field

editThe field is named for Ellwood Cooper (1829-1918), who owned the large Ellwood Ranch in what is now Goleta and the adjacent hills. His first name lingers in several local place names including the oil fields, Ellwood Canyon, Ellwood School, Ellwood Station Road, and the Goleta neighborhood "Ellwood".[10]

The first oil discovery in the area was in July 1928, by Barnsdall Oil Co. of California and the Rio Grande Company, who drilled their Luton-Bell Well No. 1 to a depth of 3,208 feet (978 m) into the Vaqueros Sandstone. After almost giving up they not only struck oil, but had a significant gusher, initially producing 1,316 barrels per day (209.2 m3/d). This discovery touched off a period of oil leasing and wildcat well drilling on the Santa Barbara south coast, from Carpinteria to Gaviota. During this period, the Mesa Oil Field was discovered, within the Santa Barbara city limits, about 12 miles (19 km) east of the Ellwood field.[11][12]

World War II shelling

editA local myth, which was told by local writer Walker A. Tompkins and others as fact, says that in the late 1930s, Kozo Nishino, the skipper of a Japanese oil tanker, visited the field and tripped and fell into a patch of prickly pear cactus, provoking laughter from a group of nearby oil workers.[10][13] The story says that Kozo came back a few years later, possibly for revenge. Kozo was a military service member who never worked on an oil tanker, as shown by Imperial Japanese Navy records that document his roles on submarines from the early 1920s through 1943.[14]

During World War II, Kozo was captain of Japanese submarine I-17, which surfaced just off of Coal Oil Point on the evening of February 23, 1942. His crew emerged and manned the sub's 5.5" deck gun. They fired between 16 and 25 rounds at a pair of oil storage tanks near where he had fallen into the cactus. His gunners were poor shots, and most of the shells went wild, exploding either miles inland on Tecolote Ranch, or splashing in the water. One of the explosions damaged well Luton-Bell 17, on the beach just below Fairway 14 of the present-day golf course, causing about $500 in damage to a catwalk and some pumping equipment. Kozo radioed Tokyo that he had "left Santa Barbara in flames."[10] This incident was the first direct naval bombardment by an enemy power on the U.S. continent since the bombardment of Orleans in World War I.[15][16][17]

The Ellwood field reached peak production in 1930, but it remained productive through the 1960s. The onshore portion was abandoned in 1972.

The site of the oilfield equipment damaged by the Japanese is Santa Barbara County property, which may be traversed by the public, on the beach below the Sandpiper Golf Course. A historical marker on a rock on the Golf Course grounds recounts the Japanese attack.[18]

South Ellwood Offshore field

editThe existence of an offshore field was suspected for a long time, largely due to the persistent natural seepage of oil from the sea floor. The Coal Oil Point seep field is now one of the most actively studied seep zones in the world. In 1966, ARCO built Platform Holly, in 211 feet (64 m) of water approximately two miles (3.2 km) southwest of Coal Oil Point, and began drilling wells into the various zones in the South Ellwood Offshore field. Peak production from the field was in 1984. Mobil operated Platform Holly until 1997, when Venoco acquired all rights to the field.[19] Three pipelines – one oil, one gas, and one for utilities – connected the platform to the processing plant on the mainland. In addition, an oil pipeline transported oil from "tents" constructed over some of the natural seeps on the ocean floor to the processing plant.[20] Leakage from the natural seeps near Platform Holly decreased substantially, probably from the decrease in reservoir pressure from the oil and gas produced at the platform.[21]

Away from Platform Holly, much of the field is still not fully explored and developed. Mobil's 1995 proposal to drill from the shore (the "Clearview" project, dubbed "Drillview" by opponents) was rejected, and a proposal to drill into the more distant parts of the field from the existing Platform Holly was under consideration in 2009. The proposal involved directionally drilling 40 new wells from the existing platform, potentially tripling its production.[22]

Platform Holly has been inactive since the Refugio Oil Spill in May 2015 ruptured the pipeline it relies on to transport oil to market. Venoco has since filed bankruptcy, and the platform is being decommissioned. Ownership of the platform has been transferred to the state, which is now responsible for removal of the structure.[23] The California State Lands Commission work to plug and abandon the wells began in 2019, with an estimated two to three years until completion.[24][25]

See also

edit- California during World War II

- Coal Oil Point seep field, large natural oil/gas leak in the Ellwood offshore oilfield.

- Asphalt volcano, includes recent underwater discoveries here.

- LA Basin

- La Goleta Gas Field

References

edit- ^ Several prominent and public sources, including the California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources, use the "Elwood" spelling in their database and publications. The fields are named after 19th-century rancher and olive grower Ellwood Cooper, and many other local place names use the "Ellwood" spelling.

- ^ Welsh, Nick (March 17, 2016). "Ellwood Oil Facility Closer to Closing?". Santa Barbara Independent. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ "Project to Remove Final Two Oil Piers at Haskell's Beach Set to Begin" (Press release). City of Goleta. August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022 – via Edhat.

- ^ Holland, Brooke (November 24, 2020). "Oil Transport from Ellwood Onshore Facility in Goleta Planned for First 2 Weeks of December". Noozhawk. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "County of Santa Barbara Energy Division page on Venoco operations". Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ "An Advanced Fracture Characterization and Well Path Navigation System for Effective Re-Development and Enhancement of Ultimate Recovery from the Complex Monterey Reservoir of the South Ellwood Field, Offshore California". netl.doe.gov. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Press release on South Ellwood project Environmental Impact Report". Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ "Oil and Gas Journal on UCSB Clearview Decision". hep.ucsb.edu. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ Vickery, Frederick (1943). Goleta Oil Field, in Geologic Formations and economic development of the Oil and Gas Fields of California. San Francisco: State of California Dept. of Natural Resources Division of Mines, Bulletin 118. pp. 377–379.

- ^ a b c Tompkins, Walker A. (1983). Santa Barbara History Makers. Santa Barbara: McNally & Loftin. pp. 161–165, 304–306. ISBN 0-87461-059-1.

- ^ Schmitt, R. J., Dugan, J. E., and M. R. Adamson. "Industrial Activity and Its Socioeconomic Impacts: Oil and Three Coastal California Counties." MMS OCS Study 2002-049. Coastal Research Center, Marine Science Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, California. MMS Cooperative Agreement Number 14-35-01-00-CA-31603. 244 pages; p. 54.

- ^ Hill, Mason (1943). Elwood Oil Field, in Geologic Formations and economic development of the Oil and Gas Fields of California. San Francisco: State of California Dept. of Natural Resources Division of Mines, Bulletin 118. pp. 380–383.

- ^ California State Military Department description of the Ellwood shelling Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Modugno, Tom (February 28, 2021). "The Sub Commander and the Cactus Myth, Debunked". Goleta History. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ German U-Boat Attacks Cape Cod

- ^ McKinney, John. California's Coastal Parks. Wilderness Press, 2005. p. 101. ISBN 0-89997-388-4

- ^ Tompkins, Walker A. It Happened in Old Santa Barbara. Sandollar Press, 1976. p. 306.

- ^ Modugno, Tom (October 19, 2014). "Attack on Ellwood". Goleta History. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Orozco, Lance (August 26, 2020). "Work Continues On Removal of Oil Platform, Oil Facilities On South Coast". KCLU News. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "County of Santa Barbara Energy Division". Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ Emission estimates for the Coal Oil Point Seep Field Archived 2017-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, August 2000, UCSB Hydrocarbon Seeps project

- ^ Margaret Connell (July 22, 2008). "Platform Holly Wants More Oil". The Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Sam Goldman (April 23, 2017). "Venoco Bankruptcy Effectively Ends Santa Barbara Channel Oil, Gas Operations in State Waters". The Mercury News. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ^ "Platform Holly / Venoco, LLC Bankruptcy". California State Lands Commission. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Vasoyan, Andy (November 25, 2020). "Thousands Of Gallons Of Oil To Be Moved From Decomissioned [sic] South Coast Well". KCLU News. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Baker, Gayle (2003). Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara: Harbor Town Histories. ISBN 0-9710984-1-7.

- Tompkins, Walker A. (1975). Santa Barbara, Past and Present. Santa Barbara: Tecolote Books.

- Tompkins, Walker A. (1976). It Happened in Old Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara: Sandollar Press.