The electricity sector in Ukraine is an important part of energy in Ukraine. Most electricity generation is nuclear.[2] The bulk of Energoatom output is sold to the government's "guaranteed buyer" to keep prices more stable for domestic customers.[3][4] Zaporizhzhia is the largest nuclear power plant in Europe. Until the 2010s all of Ukraine's nuclear fuel came from Russia, but now most does not.[5]

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Installed capacity (2020) | 54.5 [1] |

| Institutions | |

| Responsibility for transmission | Ukrenergo |

Some electricity infrastructure was destroyed in the Russo-Ukrainian War,[6][7] but wind farms and solar power are thought to be resilient because they are distributed.[8] As of 2024 about 1.7 GW can be imported from other European countries and it is hoped to increase this interconnection to 2 GW, but that will not be enough to cover peak demand.[2][9] Many small gas-turbine generators are being installed to reduce the blackouts being caused by Russian attacks.[9]

History

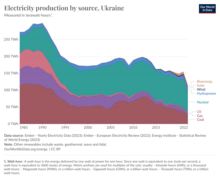

editElectricity production fell from 296 TWh in 1991 to 171 TWh in 1999, then increased slowly to 195 TWh in 2007, before falling again.[10] In 2014, consumption was 134 TWh after transmission losses of 20 TWh, with peak demand at about 28 GWe. 8 TWh was exported to Europe. In 2015 electricity production fell to about 146 TWh largely due to a fall in anthracite coal supplies caused by the War in Donbass.[11][12]

In July 2019, a new wholesale energy market was launched, intended to bring real competition in the generation market and help future integration with Europe. The change was a prerequisite for receiving European Union assistance. It led to in increased price for industrial consumers of between 14% and 28% during July. The bulk of Energoatom output is sold to the government's "guaranteed buyer" to keep prices more stable for domestic customers.[3][4]

Grid synchronisation with Europe

editSince 2017 Ukraine sought to divest itself of dependency on the Unified Power System of Russia (UPS) and instead connect westwards to the synchronous grid of Continental Europe, thereby participating in European electricity markets.[13][14] Power lines coupling the country to the grids of neighbouring Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary existed, but were de-energised.

A necessary prerequisite of Ukrainian integration was for the country to successfully demonstrate it was capable of running in a islanded manner, maintaining satisfactory control of its own frequency. To do that would require disconnection from the UPS grid, and a date of 24 February 2022 was set. This proved to be the date Russia invaded Ukraine, but the disconnection nonetheless proceeded to schedule. Ukraine placed an urgent request to synchronise with the European grid to ENTSO-E, the European collective of transmission system operators of which it was a member, and on 16 March 2022 the western circuits were energised, bringing both Ukraine and Moldova, which is coupled to the Ukrainian grid, into the European synchronised grid.[15][16][17] On 16 March 2022 a trial synchronisation started of the Ukraine and Moldova grid with the European grid.[15]

War damage

editRussia launched waves of missile and drone strikes against energy in Ukraine as part of its invasion.[18] From 2022 the strikes targeted civilian areas beyond the battlefield, particularly critical power infrastructure,[19][20] which is considered a war crime.[21][22] By mid-2024 the country only had a third of pre-war electricity generating capacity, and some gas distribution and district heating had been hit.[23]

On 10 October 2022 Russia attacked the power grid throughout Ukraine, including the in Kyiv, with a wave of 84 cruise missiles and 24 suicide drones.[24] Further waves struck Ukrainian infrastructure, killing and injuring many, and seriously affecting energy distribution across Ukraine and neighboring countries. By 19 November, nearly half of the country's power grid was out of commission, and 10 million Ukrainians were without electricity, according to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.[25] By mid-December, Russia had fired more than 1,000 missiles and drones at Ukraine's energy grid.[26] Several waves targeted Kyiv, including one on 16 May 2023 in which Ukraine said it had intercepted six Kinzhal missiles.

Deliberately depriving Ukrainians of electricity and heating during the cold winter months was the biggest attack on a nation's health since World War II.[27] The attacks on power stations inflicted large economic and practical costs on Ukraine.[28] The UK Defense Ministry said the strikes were intended to demoralize the population and force the Ukrainian leadership to capitulate.[29] This is widely deemed to have failed.[30][31]

The strikes were condemned internationally, with the European Commission describing them as "barbaric"[32] and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg calling them "horrific and indiscriminate".[33] President Zelenskyy described the strikes as "absolute evil" and "terrorism".[34] The International Criminal Court (ICC) indicted four Russian officials for war crimes connected with attacks against civilian infrastructure, including former Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu and Head of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation Valery Gerasimov.Generation

editNuclear

editUkraine operates four nuclear power plants with 15 reactors located in Volhynia and South Ukraine.[35] The total installed nuclear power capacity is over 13 GWe, ranking 7th in the world in 2020.[36] Energoatom, a Ukrainian state enterprise, operates all four active nuclear power stations in Ukraine.[37] In 2019, nuclear power supplied over 20% of Ukraine's energy.[38]

In 2021, Ukraine's nuclear reactors produced 81 TWh — over 55% of its total electricity generation,[39] and the second-highest share in the world, behind only France. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, is in Ukraine.

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster in northern Ukraine was the world's most severe nuclear accident to date.

Lack of coal for Ukraine's coal-fired power stations due to the war in Donbas and a shut down of one of the six reactors of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant led to rolling blackouts throughout the country in December 2014. Due to the Russo-Ukrainian War, the nuclear power plant has been damaged.Hydro

editGas

editMany small gas-turbine generators are used, as these are more difficult to attack than large gas-fired or coal-fired power plants.[41]

Imports, storage, transmission and distribution

editThe IEA says that capacity limits on links from neighbouring countries should be increased, and that more decentralised generation and batteries should be installed for energy security.[42] They recommend more off-grid and mini-grid. Both transmission and distribution have been attacked,[42] and shelters have been built to protect substations from attack.[43][44] More storage is being installed.[45]

External links

edit- Live electricity import and export electricityMap Live built by Tomorrow

References

edit- ^ "How Ukraine is keeping the lights on under Russian fire".

- ^ a b "How Ukraine is keeping the lights on under Russian fire".

- ^ a b Prokip, Andrian (6 May 2019). "Liberalizing Ukraine's Electricity Market: Benefits and Risks". Wilson Center. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ a b Kossov, Igor (2 August 2019). "New energy market brings controversy". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Westinghouse and Ukraine's Energoatom Extend Long-term Nuclear Fuel Contract". 11 April 2014. Westinghouse. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Lock, Samantha (2022-02-27). "Russia-Ukraine latest news: missile strikes on oil facilities reported as some Russian banks cut off from Swift system – live". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Taylor, Kira (2022-02-26). "Ukraine's energy system coping but risks major damage as war continues". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ "Russia changes tack on targeting Ukraine's energy plants". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ a b Stern, David L. (2024-07-06). "Russia destroyed Ukraine's energy sector, so it's being rebuilt green". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in Ukraine". World Nuclear Association. February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Poroshenko: Ukraine increasing nuclear share to 60%". World Nuclear News. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Poroshenko: Share of nuclear power grows to 60% amid blockade of trade with Donbas". UNIAN. 16 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Feldhaus, Lukas; Westphal, Kirsten; Zachmann, Georg (24 November 2021). "Connecting Ukraine to Europe's Electricity Grid". SWP Comment. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. doi:10.18449/2021C57. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Abnett, Kate; Strzelecki, Marek (1 April 2022). "Explainer: Europe and Ukraine's plan to link power grids". Reuters. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Continental Europe successful synchronisation with Ukraine and Moldova power systems". ENTSO-E. 16 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Böttcher, Philipp C.; Gorjão, Leonardo Rydin; Beck, Christian; Jumar, Richard; Maass, Heiko; Hagenmeyer, Veit; Witthaut, Dirk; Schäfer, Benjamin (15 April 2022). "Initial analysis of the impact of the Ukrainian power grid synchronization with Continental Europe". arXiv:2204.07508.

- ^ "Ukraine joins European power grid, ending its dependence on Russia". CBS News. No. 16 March 2022. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Meilhan, Pierre; Roth, Richard (22 October 2022). "Ukrainian military says 18 Russian cruise missiles destroyed amid attacks on energy infrastructure". CNN International. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Olearchyk, Roman; Srivastava, Mehul; Seddon, Max; Miller, Christopher (10 October 2022). "Vladimir Putin says Russia launched strikes on Ukraine over Crimea bridge explosion". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: Russian large-scale strikes are 'unacceptable escalation', says Guterres". 10 October 2022. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Zelenskiy asks G7 for monitoring of Ukraine's border with Belarus". the Guardian. 2022-10-11. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Ukraine: Russian attacks on critical energy infrastructure amount to war crimes". Amnesty International. 20 October 2022. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Ukraine's Energy Security and the Coming Winter – Analysis. International Energy Agency (Report). September 2024.

- ^ "Russia rains missiles down on Ukraine's capital and other cities in retaliation for Crimea bridge blast". CBS News. 10 October 2022. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Almost half Ukraine's energy system disabled, PM says". BBC News. 18 November 2022. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- Santora, Marc; Bigg, Matthew Mpoke; Nechepurenko, Ivan (2022-12-02). "Brace for Bombs, Fix and Repeat: Ukraine's Grim Efforts to Restore Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Terajima, Asami (2022-12-09). "Ukraine war latest: Power deficit still 'significant' after Russia launches 'more than 1,000 missiles and drones' at Ukrainian energy since October". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ^ "En Ukraine, " l'hiver qui s'installe fait dorénavant de la santé une préoccupation prioritaire "". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2022-12-08. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^

Kraemer, Christian (2022-10-26). "Russian bombings of civilian infrastructure raise cost of Ukraine's recovery: IMF". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- Birnbaum, Michael; Stern, David L.; Rauhala, Emily (October 25, 2022). "Russia's methodical attacks exploit frailty of Ukrainian power system". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Santora, Marc (2022-10-29). "Zelensky says that some four million Ukrainians face restrictions on power use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- ^ "UK Defense Ministry: Russia's strategy of attacking Ukraine's critical infrastructure becoming less effective". The Kyiv Independent. The Kyiv Independent news. 2022-12-01. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- Stephens, Bret (2022-11-01). "Opinion | Don't Let Putin Turn Ukraine into Aleppo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ "How Ukraine tamed Russian missile barrages and kept the lights on". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

- ^ Pietralunga, Cédric (2023-04-13). "Russia fails to break Ukraine morale by targeting energy infrastructure". Le Monde. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

- ^ "EU condemns 'barbaric' Russian missile attacks, warns Belarus". Reuters. 2022-10-10. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ Mueller, Julia (2022-10-10). "NATO chief condemns 'horrific & indiscriminate' Russian attacks on Ukraine". Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Ukraine live briefing: Putin, Zelensky trade accusations of 'terrorism' as bloody weekend ebbs". 2022-10-09. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ Nuclear fuel imports from Sweden account for 41.6% in H1, balance from Russia, UNIAN (22 August 2016)

- ^ "PRIS – Miscellaneous reports – Nuclear Share". pris.iaea.org. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Energoatom chief Kim overstepped his powers when signing contract, failed to show up for questioning, says interior minister, Interfax-Ukraine (12 June 2013)

- ^ "Primary energy consumption by source". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ "Nuclear Share of Electricity Generation in 2021". IAEA. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "First online auction for the allocation of the renewable energy support quota announced in Prozorro.Sale". validate.perfdrive.com. Retrieved 2024-10-26.

- ^ "Russia destroyed Ukraine's energy sector, so it's being rebuilt green".

- ^ a b Ukraine's Energy Security and the Coming Winter – Analysis. International Energy Agency (Report). September 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine energy chief ousted in 'politically motivated' move". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ Kottasová, Ivana (2024-08-27). "How Ukrainians learned to live with wartime blackouts". CNN. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ Ross, Kelvin (2024-10-01). "Yuliana Onishchuk: The gamechanger on a mission for Ukraine". Enlit World. Retrieved 2024-10-26.