In electricity generation, a generator[1] is a device that converts motion-based power (potential and kinetic energy) or fuel-based power (chemical energy) into electric power for use in an external circuit. Sources of mechanical energy include steam turbines, gas turbines, water turbines, internal combustion engines, wind turbines and even hand cranks. The first electromagnetic generator, the Faraday disk, was invented in 1831 by British scientist Michael Faraday. Generators provide nearly all the power for electrical grids.

In addition to electricity- and motion-based designs, photovoltaic and fuel cell powered generators use solar power and hydrogen-based fuels, respectively, to generate electrical output.

The reverse conversion of electrical energy into mechanical energy is done by an electric motor, and motors and generators are very similar. Many motors can generate electricity from mechanical energy.

Terminology

editElectromagnetic generators fall into one of two broad categories, dynamos and alternators.

- Dynamos generate pulsing direct current through the use of a commutator.

- Alternators generate alternating current.

Mechanically, a generator consists of a rotating part and a stationary part which together form a magnetic circuit:

- Rotor: The rotating part of an electrical machine.

- Stator: The stationary part of an electrical machine, which surrounds the rotor.

One of these parts generates a magnetic field, the other has a wire winding in which the changing field induces an electric current:

- Field winding or field (permanent) magnets: The magnetic field-producing component of an electrical machine. The magnetic field of the dynamo or alternator can be provided by either wire windings called field coils or permanent magnets. Electrically-excited generators include an excitation system to produce the field flux. A generator using permanent magnets (PMs) is sometimes called a magneto, or a permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG).

- Armature: The power-producing component of an electrical machine. In a generator, alternator, or dynamo, the armature windings generate the electric current, which provides power to an external circuit.

The armature can be on either the rotor or the stator, depending on the design, with the field coil or magnet on the other part.

History

editBefore the connection between magnetism and electricity was discovered, electrostatic generators were invented. They operated on electrostatic principles, by using moving electrically charged belts, plates and disks that carried charge to a high potential electrode. The charge was generated using either of two mechanisms: electrostatic induction or the triboelectric effect. Such generators generated very high voltage and low current. Because of their inefficiency and the difficulty of insulating machines that produced very high voltages, electrostatic generators had low power ratings, and were never used for generation of commercially significant quantities of electric power. Their only practical applications were to power early X-ray tubes, and later in some atomic particle accelerators.

Faraday disk generator

editThe operating principle of electromagnetic generators was discovered in the years of 1831–1832 by Michael Faraday. The principle, later called Faraday's law, is that an electromotive force is generated in an electrical conductor which encircles a varying magnetic flux.

Faraday also built the first electromagnetic generator, called the Faraday disk; a type of homopolar generator, using a copper disc rotating between the poles of a horseshoe magnet. It produced a small DC voltage.

This design was inefficient, due to self-cancelling counterflows of current in regions of the disk that were not under the influence of the magnetic field. While current was induced directly underneath the magnet, the current would circulate backwards in regions that were outside the influence of the magnetic field. This counterflow limited the power output to the pickup wires and induced waste heating of the copper disc. Later homopolar generators would solve this problem by using an array of magnets arranged around the disc perimeter to maintain a steady field effect in one current-flow direction.

Another disadvantage was that the output voltage was very low, due to the single current path through the magnetic flux. Experimenters found that using multiple turns of wire in a coil could produce higher, more useful voltages. Since the output voltage is proportional to the number of turns, generators could be easily designed to produce any desired voltage by varying the number of turns. Wire windings became a basic feature of all subsequent generator designs.

Jedlik and the self-excitation phenomenon

editIndependently of Faraday, Ányos Jedlik started experimenting in 1827 with the electromagnetic rotating devices which he called electromagnetic self-rotors. In the prototype of the single-pole electric starter (finished between 1852 and 1854) both the stationary and the revolving parts were electromagnetic. It was also the discovery of the principle of dynamo self-excitation,[2] which replaced permanent magnet designs. He also may have formulated the concept of the dynamo in 1861 (before Siemens and Wheatstone) but did not patent it as he thought he was not the first to realize this.[3]

Direct current generators

editA coil of wire rotating in a magnetic field produces a current which changes direction with each 180° rotation, an alternating current (AC). However many early uses of electricity required direct current (DC). In the first practical electric generators, called dynamos, the AC was converted into DC with a commutator, a set of rotating switch contacts on the armature shaft. The commutator reversed the connection of the armature winding to the circuit every 180° rotation of the shaft, creating a pulsing DC current. One of the first dynamos was built by Hippolyte Pixii in 1832.

The dynamo was the first electrical generator capable of delivering power for industry. The Woolrich Electrical Generator of 1844, now in Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, is the earliest electrical generator used in an industrial process.[4] It was used by the firm of Elkingtons for commercial electroplating.[5][6][7]

The modern dynamo, fit for use in industrial applications, was invented independently by Sir Charles Wheatstone, Werner von Siemens and Samuel Alfred Varley. Varley took out a patent on 24 December 1866, while Siemens and Wheatstone both announced their discoveries on 17 January 1867 by delivering papers at the Royal Society.[8][9]

The "dynamo-electric machine" employed self-powering electromagnetic field coils rather than permanent magnets to create the stator field.[10] Wheatstone's design was similar to Siemens', with the difference that in the Siemens design the stator electromagnets were in series with the rotor, but in Wheatstone's design they were in parallel.[8][9] The use of electromagnets rather than permanent magnets greatly increased the power output of a dynamo and enabled high power generation for the first time. This invention led directly to the first major industrial uses of electricity. For example, in the 1870s Siemens used electromagnetic dynamos to power electric arc furnaces for the production of metals and other materials.

The dynamo machine that was developed consisted of a stationary structure, which provides the magnetic field, and a set of rotating windings which turn within that field. On larger machines the constant magnetic field is provided by one or more electromagnets, which are usually called field coils.

Large power generation dynamos are now rarely seen due to the now nearly universal use of alternating current for power distribution. Before the adoption of AC, very large direct-current dynamos were the only means of power generation and distribution. AC has come to dominate due to the ability of AC to be easily transformed to and from very high voltages to permit low losses over large distances.

Synchronous generators (alternating current generators)

editThrough a series of discoveries, the dynamo was succeeded by many later inventions, especially the AC alternator, which was capable of generating alternating current. It is commonly known to be the Synchronous Generators (SGs). The synchronous machines are directly connected to the grid and need to be properly synchronized during startup.[11] Moreover, they are excited with special control to enhance the stability of the power system.[12]

Alternating current generating systems were known in simple forms from Michael Faraday's original discovery of the magnetic induction of electric current. Faraday himself built an early alternator. His machine was a "rotating rectangle", whose operation was heteropolar: each active conductor passed successively through regions where the magnetic field was in opposite directions.[13]

Large two-phase alternating current generators were built by a British electrician, J. E. H. Gordon, in 1882. The first public demonstration of an "alternator system" was given by William Stanley Jr., an employee of Westinghouse Electric in 1886.[14]

Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti established Ferranti, Thompson and Ince in 1882, to market his Ferranti-Thompson Alternator, invented with the help of renowned physicist Lord Kelvin.[15] His early alternators produced frequencies between 100 and 300 Hz. Ferranti went on to design the Deptford Power Station for the London Electric Supply Corporation in 1887 using an alternating current system. On its completion in 1891, it was the first truly modern power station, supplying high-voltage AC power that was then "stepped down" for consumer use on each street. This basic system remains in use today around the world.

After 1891, polyphase alternators were introduced to supply currents of multiple differing phases.[16] Later alternators were designed for varying alternating-current frequencies between sixteen and about one hundred hertz, for use with arc lighting, incandescent lighting and electric motors.[17]

Self-excitation

editAs the requirements for larger scale power generation increased, a new limitation rose: the magnetic fields available from permanent magnets. Diverting a small amount of the power generated by the generator to an electromagnetic field coil allowed the generator to produce substantially more power. This concept was dubbed self-excitation.

The field coils are connected in series or parallel with the armature winding. When the generator first starts to turn, the small amount of remanent magnetism present in the iron core provides a magnetic field to get it started, generating a small current in the armature. This flows through the field coils, creating a larger magnetic field which generates a larger armature current. This "bootstrap" process continues until the magnetic field in the core levels off due to saturation and the generator reaches a steady state power output.

Very large power station generators often utilize a separate smaller generator to excite the field coils of the larger. In the event of a severe widespread power outage where islanding of power stations has occurred, the stations may need to perform a black start to excite the fields of their largest generators, in order to restore customer power service.

Specialised types of generator

editDirect current (DC)

editA dynamo uses commutators to produce direct current. It is self-excited, i.e. its field electromagnets are powered by the machine's own output. Other types of DC generators use a separate source of direct current to energise their field magnets.

Homopolar generator

editA homopolar generator is a DC electrical generator comprising an electrically conductive disc or cylinder rotating in a plane perpendicular to a uniform static magnetic field. A potential difference is created between the center of the disc and the rim (or ends of the cylinder), the electrical polarity depending on the direction of rotation and the orientation of the field.

It is also known as a unipolar generator, acyclic generator, disk dynamo, or Faraday disc. The voltage is typically low, on the order of a few volts in the case of small demonstration models, but large research generators can produce hundreds of volts, and some systems have multiple generators in series to produce an even larger voltage.[18] They are unusual in that they can produce tremendous electric current, some more than a million amperes, because the homopolar generator can be made to have very low internal resistance.

Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) generator

editA magnetohydrodynamic generator directly extracts electric power from moving hot gases through a magnetic field, without the use of rotating electromagnetic machinery. MHD generators were originally developed because the output of a plasma MHD generator is a flame, well able to heat the boilers of a steam power plant. The first practical design was the AVCO Mk. 25, developed in 1965. The U.S. government funded substantial development, culminating in a 25 MW demonstration plant in 1987. In the Soviet Union from 1972 until the late 1980s, the MHD plant U 25 was in regular utility operation on the Moscow power system with a rating of 25 MW, the largest MHD plant rating in the world at that time.[19] MHD generators operated as a topping cycle are currently (2007) less efficient than combined cycle gas turbines.

Alternating current (AC)

editInduction generator

editInduction AC motors may be used as generators, turning mechanical energy into electric current. Induction generators operate by mechanically turning their rotor faster than the simultaneous speed, giving negative slip. A regular AC non-simultaneous motor usually can be used as a generator, without any changes to its parts. Induction generators are useful in applications like minihydro power plants, wind turbines, or in reducing high-pressure gas streams to lower pressure, because they can recover energy with relatively simple controls. They do not require another circuit to start working because the turning magnetic field is provided by induction from the one they have. They also do not require speed governor equipment as they inherently operate at the connected grid frequency.

An induction generator must be powered with a leading voltage; this is usually done by connection to an electrical grid, or by powering themselves with phase correcting capacitors.

Linear electric generator

editIn the simplest form of linear electric generator, a sliding magnet moves back and forth through a solenoid, a copper wire or a coil. An alternating current is induced in the wire, or loops of wire, by Faraday's law of induction each time the magnet slides through. This type of generator is used in the Faraday flashlight. Larger linear electricity generators are used in wave power schemes.

Variable-speed constant-frequency generators

editGrid-connected generators deliver power at a constant frequency. For generators of the synchronous or induction type, the primer mover speed turning the generator shaft must be at a particular speed (or narrow range of speed) to deliver power at the required utility frequency. Mechanical speed-regulating devices may waste a significant fraction of the input energy to maintain a required fixed frequency.

Where it is impractical or undesired to tightly regulate the speed of the prime mover, doubly fed electric machines may be used as generators. With the assistance of power electronic devices, these can regulate the output frequency to a desired value over a wider range of generator shaft speeds. Alternatively, a standard generator can be used with no attempt to regulate frequency, and the resulting power converted to the desired output frequency with a rectifier and converter combination. Allowing a wider range of prime mover speeds can improve the overall energy production of an installation, at the cost of more complex generators and controls. For example, where a wind turbine operating at fixed frequency might be required to spill energy at high wind speeds, a variable speed system can allow recovery of energy contained during periods of high wind speed.

Common use cases

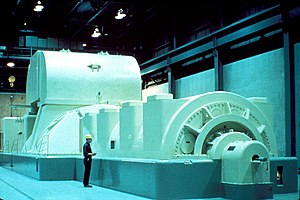

editPower station

editA power station, also known as a power plant or powerhouse and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility that generates electricity. Most power stations contain one or more generators, or spinning machines converting mechanical power into three-phase electrical power. The relative motion between a magnetic field and a conductor creates an electric current. The energy source harnessed to turn the generator varies widely. Most power stations in the world burn fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas to generate electricity. Cleaner sources include nuclear power, and increasingly use renewables such as the sun, wind, waves and running water.

Vehicular generators

editRoadway vehicles

editMotor vehicles require electrical energy to power their instrumentation, keep the engine itself operating, and recharge their batteries. Until about the 1960s motor vehicles tended to use DC generators (dynamos) with electromechanical regulators. Following the historical trend above and for many of the same reasons, these have now been replaced by alternators with built-in rectifier circuits.

Bicycles

editBicycles require energy to power running lights and other equipment. There are two common kinds of generator in use on bicycles: bottle dynamos which engage the bicycle's tire on an as-needed basis, and hub dynamos which are directly attached to the bicycle's drive train. The name is conventional as they are small permanent-magnet alternators, not self-excited DC machines as are dynamos. Some electric bicycles are capable of regenerative braking, where the drive motor is used as a generator to recover some energy during braking.

Sailboats

editSailing boats may use a water- or wind-powered generator to trickle-charge the batteries. A small propeller, wind turbine or turbine is connected to a low-power generator to supply currents at typical wind or cruising speeds.

Recreational vehicles

editRecreational vehicles need an extra power supply to power their onboard accessories, including air conditioning units, and refrigerators. An RV power plug is connected to the electric generator to obtain a stable power supply.[20]

Electric scooters

editElectric scooters with regenerative braking have become popular all over the world. Engineers use kinetic energy recovery systems on the scooter to reduce energy consumption and increase its range up to 40-60% by simply recovering energy using the magnetic brake, which generates electric energy for further use. Modern vehicles reach speed up to 25–30 km/h and can run up to 35–40 km.

Genset

editAn engine-generator is the combination of an electrical generator and an engine (prime mover) mounted together to form a single piece of self-contained equipment. The engines used are usually piston engines, but gas turbines can also be used, and there are even hybrid diesel-gas units, called dual-fuel units. Many different versions of engine-generators are available – ranging from very small portable petrol powered sets to large turbine installations. The primary advantage of engine-generators is the ability to independently supply electricity, allowing the units to serve as backup power sources.[21]

Human powered electrical generators

editA generator can also be driven by human muscle power (for instance, in field radio station equipment).

Human powered electric generators are commercially available, and have been the project of some DIY enthusiasts. Typically operated by means of pedal power, a converted bicycle trainer, or a foot pump, such generators can be practically used to charge batteries, and in some cases are designed with an integral inverter. An average "healthy human" can produce a steady 75 watts (0.1 horsepower) for a full eight hour period, while a "first class athlete" can produce approximately 298 watts (0.4 horsepower) for a similar period, at the end of which an undetermined period of rest and recovery will be required. At 298 watts, the average "healthy human" becomes exhausted within 10 minutes.[23] The net electrical power that can be produced will be less, due to the efficiency of the generator. Portable radio receivers with a crank are made to reduce battery purchase requirements, see clockwork radio. During the mid 20th century, pedal powered radios were used throughout the Australian outback, to provide schooling (School of the Air), medical and other needs in remote stations and towns.

Mechanical measurement

editA tachogenerator is an electromechanical device which produces an output voltage proportional to its shaft speed. It may be used for a speed indicator or in a feedback speed control system. Tachogenerators are frequently used to power tachometers to measure the speeds of electric motors, engines, and the equipment they power. Generators generate voltage roughly proportional to shaft speed. With precise construction and design, generators can be built to produce very precise voltages for certain ranges of shaft speeds.[citation needed]

Equivalent circuit

edit- G, generator

- VG, generator open-circuit voltage

- RG, generator internal resistance

- VL, generator on-load voltage

- RL, load resistance

An equivalent circuit of a generator and load is shown in the adjacent diagram. The generator is represented by an abstract generator consisting of an ideal voltage source and an internal impedance. The generator's and parameters can be determined by measuring the winding resistance (corrected to operating temperature), and measuring the open-circuit and loaded voltage for a defined current load.

This is the simplest model of a generator, further elements may need to be added for an accurate representation. In particular, inductance can be added to allow for the machine's windings and magnetic leakage flux,[24] but a full representation can become much more complex than this.[25]

See also

edit- Diesel generator

- Electricity generation

- Electric motor

- Engine-generator

- Faraday's law of induction

- Gas turbine

- Generation expansion planning

- Goodness factor

- Hydropower

- Steam generator (boiler)

- Steam generator (railroad)

- Steam turbine

- Superconducting electric machine

- Thermoelectric generator

- Thermal power station

- Tidal stream generator

References

edit- ^ Also called electric generator, electrical generator, and electromagnetic generator.

- ^ Augustus Heller (April 2, 1896). "Anianus Jedlik". Nature. 53 (1379). Norman Lockyer: 516. Bibcode:1896Natur..53..516H. doi:10.1038/053516a0.

- ^ Augustus Heller (2 April 1896), "Anianus Jedlik", Nature, 53 (1379), Norman Lockyer: 516, Bibcode:1896Natur..53..516H, doi:10.1038/053516a0

- ^ Birmingham Museums trust catalogue, accession number: 1889S00044

- ^ Thomas, John Meurig (1991). Michael Faraday and the Royal Institution: The Genius of Man and Place. Bristol: Hilger. p. 51. ISBN 978-0750301459.

- ^ Beauchamp, K G (1997). Exhibiting Electricity. IET. p. 90. ISBN 9780852968956.

- ^ Hunt, L. B. (March 1973). "The early history of gold plating". Gold Bulletin. 6 (1): 16–27. doi:10.1007/BF03215178.

- ^ a b Siemens, Charles William (1867). "II. On the conversion of dynamical into electrical force without the aid of permanent magnetism". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 15: 367–369. doi:10.1098/rspl.1866.0082.

- ^ a b Wheatstone, Charles (1867). "III. On the augmentation of the power of a magnet by the reaction thereon of currents induced by the magnet itself". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 15: 369–372. doi:10.1098/rspl.1866.0083.

- ^ Berliner Berichte. January 1867.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Schaefer, Richard C. (Jan–Feb 2017). "Art of Generator Synchronizing". IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. 53 (1): 751–757. doi:10.1109/tia.2016.2602215. ISSN 0093-9994. S2CID 15682853.

- ^ Basler, Michael J.; Schaefer, Richard C. (2008). "Understanding Power-System Stability". IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. 44 (2): 463–474. doi:10.1109/tia.2008.916726. ISSN 0093-9994. S2CID 62801526.

- ^ Thompson, Sylvanus P., Dynamo-Electric Machinery. p. 7

- ^ Blalock, Thomas J., "Alternating Current Electrification, 1886". IEEE History Center, IEEE Milestone. (ed. first practical demonstration of a dc generator – ac transformer system.)

- ^ Ferranti Timeline Archived October 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine – Museum of Science and Industry (Accessed 22-02-2012)

- ^ Thompson, Sylvanus P., Dynamo-Electric Machinery. p. 17

- ^ Thompson, Sylvanus P., Dynamo-Electric Machinery. p. 16

- ^ Losty, H.H.W & Lewis, D.L. (1973) "Homopolar Machines". Philosophical Transactions for the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 275 (1248), 69–75

- ^ Langdon Crane, Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Power Generator: More Energy from Less Fuel, Issue Brief Number IB74057, Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, 1981, retrieved from Digital.library.unt.edu 18 July 2008

- ^ Markovich, Tony (2021-09-14). "What Your Camper or RV Needs For Living Off-Grid". Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ "Hurricane Preparedness: Protection Provided by Power Generators | Power On with Mark Lum". Wpowerproducts.com. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- ^ With Generators Gone, Wall Street Protesters Try Bicycle Power, Colin Moynihan, New York Times, 30 October 2011; accessed 2 November 2011

- ^ "Program: hpv (updated 6/22/11)". Ohio.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- ^ Geoff Klempner, Isidor Kerszenbaum, "1.7.4 Equivalent circuit", Handbook of Large Turbo-Generator Operation and Maintenance, John Wiley & Sons, 2011 (Kindle edition) ISBN 1118210409.

- ^ Yoshihide Hase, "10: Theory of generators", Handbook of Power System Engineering, John Wiley & Sons, 2007 ISBN 0470033665.