The El Rancho Hotel and Casino (formerly known as the Thunderbird and Silverbird) was a hotel and casino that operated on the Las Vegas Strip in Winchester, Nevada. It originally opened on September 2, 1948, as the Navajo-themed Thunderbird. At the time, it was owned by building developer Marion Hicks and Lieutenant Governor of Nevada Clifford A. Jones. A sister property, the Algiers Hotel, was opened south of the Thunderbird in 1953. During the mid-1950s, the state carried out an investigation to determine whether underworld Mafia figures held hidden interests in the resort. Hicks and Jones ultimately prevailed and kept their gaming licenses. Hicks died in 1961, and his position as managing director was taken over by Joe Wells, another partner in the resort. Wells added a horse racing track known as Thunderbird Downs, located behind the resort. The Thunderbird also hosted numerous entertainers and shows, including Flower Drum Song and South Pacific.

| El Rancho Hotel and Casino | |

|---|---|

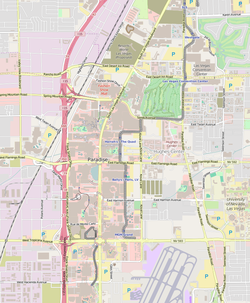

| Location | Winchester, Nevada, U.S. |

| Address | 2755 South Las Vegas Boulevard |

| Opening date | September 2, 1948 |

| Closing date | July 6, 1992 |

| Theme | Navajo (as Thunderbird) Western (as El Rancho) |

| No. of rooms | 79 (1948) 206 (1950) 460 (1976) 385 (1977) 1,007 (1992) |

| Total gaming space | 90,000 sq ft (8,400 m2) (as of 1990) |

| Signature attractions | Thunderbird Downs horse track |

| Notable restaurants | Joe's Oyster Bar |

| Casino type | Land-based |

| Owner | List

|

| Architect | Martin Stern Jr. (1965; 1980s) |

| Previous names | Thunderbird (1948–77) Silverbird (1977–82) |

| Renovated in | 1962–63, 1965, 1977, 1982, 1987–88 |

| Coordinates | 36°8′15″N 115°9′32″W / 36.13750°N 115.15889°W |

Business at the resort declined as ownership changed several times. In 1965, Wells and Jones sold the Thunderbird to Del E. Webb Corporation, which later sold it to Caesars World in 1972. Caesars World planned to demolish the Thunderbird and construct a $150 million resort in its place, but the project was canceled because of a lack of financing. The Thunderbird was sold to Tiger Investment Company, which leased it to Major Riddle starting in 1977. Riddle renovated and expanded the resort, and renamed it as the Silverbird, hoping to reinvigorate it. After Riddle's death in 1980, the Silverbird was taken over by his estate. The resort closed on December 3, 1981, after an auction failed to produce a buyer on the lease. Ed Torres subsequently purchased the Silverbird and reopened it as the El Rancho on August 31, 1982. The resort featured a western theme and was named after the original El Rancho Vegas across the street. Torres added a 13-story hotel tower in 1988.

The El Rancho closed on July 6, 1992, unable to compete with newer mega-resorts. It sat vacant for the next eight years while two companies made several failed attempts to reopen or replace the resort. A news investigation later found the decrepit buildings to be in violation of health and safety regulations. Turnberry Associates purchased the El Rancho and its 20 acres in May 2000. The company had been developing the Turnberry Place high-rise condominiums on 15 acres located behind the El Rancho. The closed resort was considered an eyesore for the new project, so Turnberry Associates had it demolished. The El Rancho's last remaining building, the 13-story hotel tower, was imploded on October 3, 2000. The former property of the El Rancho and Algiers later became the site of the Fontainebleau Las Vegas resort, which began construction in 2007 and opened on December 13, 2023, after delays.

History

editThunderbird (1948–77)

editThe resort originally opened as the Thunderbird, owned by building developer Marion Hicks and Lieutenant Governor of Nevada Clifford A. Jones.[1] Hicks had previously built the El Cortez hotel-casino, which opened in downtown Las Vegas in 1941.[2] Joe Wells, the father of actress Dawn Wells,[3] was also a partner in the Thunderbird.[4] The hotel project, originally known as the Nevada Ambassador, was announced in March 1946. It was to cost $1 million, and would be built on Highway 91 in the Las Vegas Valley,[5] on what would later become the Las Vegas Strip.[6] Construction was underway in October 1947.[7]

The Thunderbird opened on September 2, 1948,[1][8] with 79 hotel rooms, a casino, and a bar. The cost of construction exceeded $2 million.[9] The Thunderbird was the fourth resort to open on the Strip, and was located diagonally across the street from the El Rancho Vegas. It was named after the mythical Thunderbird creature,[6][1] and the entrance featured two large, neon Thunderbird statues.[6][10][11][12] The Thunderbird was considered a luxurious resort, and a Southwestern/Navajo theme was featured throughout the property, including portraits of American Indians.[13]

In February 1949, there were plans to add a 78-room hotel addition at a cost of $750,000.[14] The hotel had expanded to 206 rooms by 1950.[6] In 1953, the Thunderbird opened the adjacent 110-room Algiers Hotel, built south of the resort. It served as a sister property to deal with overflow guests of the Thunderbird.[6][15] In its early years, the Thunderbird served as a popular meeting place for local politicians.[16]

Alleged Mafia ties

editIn October 1954, articles in the Las Vegas Sun alleged that Jake and Meyer Lansky, both underworld Mafia figures, held hidden shares in the hotel. A state investigation was soon launched to determine whether the reports were true.[17][18][19] The Thunderbird's complex ownership setup was a subject of questioning during a Nevada Tax Commission hearing later that month, part of the larger investigation into the resort's ownership.[20][21] The property beneath the Thunderbird was owned by Bonanza Hotel, Inc, which operated the hotel portion and leased out other portions. Bonanza did not receive any of the resort's gaming revenue, and did not have stockholders. The casino, bars, and restaurants were operated by Thunderbird Hotel Company, of which Jones held an 11-percent interest.[21] Hicks held 51-percent ownership of the resort.[17] Both men denied that the Lanskys were involved in the Thunderbird.[20][22]

Hank Greenspun, the publisher of the Las Vegas Sun, was a critic of Jones, who alleged that Greenspun was creating a "reign of terror" in southern Nevada: "No one is secure. You can't use your phone, you can't be seen with your friends for fear that will be ballooned into a sinister incident."[21] At the end of 1954, the Thunderbird was ordered to show cause at a future hearing as to why its gaming license should not be revoked or suspended.[23] The investigation continued into 1955,[24][25] and another tax commission hearing was held that February, during which Jones criticized Greenspun. According to Jones, Greenspun was upset that the Thunderbird would not advertise in the Las Vegas Sun. Jones said that Greenspun had made repeated threats to run Hicks and himself out of town with his newspaper.[26][27]

During construction of the Thunderbird, Hicks had received a loan from George Sadlo, a business associate of the Lanskys. Sadlo later assigned half of the loan to Jake Lansky, without informing Hicks.[28] The investigation revealed that Hicks had made interest payments to Jake Lansky from 1951 to 1954.[26] The loan was perceived by the tax commission as a hidden interest in the Thunderbird. On April 1, 1955, the commission ruled that Hicks and Jones had to dispose of their interest in the Thunderbird within two months. Otherwise, the resort's gaming license would be suspended.[28] It was the first time in Nevada history that such strict action had been taken against a major casino operation. It was part of an effort by the state to prevent underworld involvement in gambling.[29]

In May 1955, the Dallas-based Southwest Securities Company expressed interest in leasing the Thunderbird,[30] although this did not come to fruition.[31] Later in the month, Hicks and Jones won a temporary restraining order that blocked their ouster from the resort. The court action was filed on behalf of Thunderbird stockholders, including Hicks, Jones, and Wells.[32][33] The Thunderbird continued to operate while both sides prepared for a legal battle over a permanent injunction.[34]

Final arguments were underway in October 1955,[35] as attorneys for the Thunderbird questioned current and former employees of the tax commission. Nevada governor Charles H. Russell, also the chairman of the tax commission, had been running for re-election in 1954. The allegations against the Thunderbird had come to light a month prior to the election, and the hotel alleged that the timing of the claims was politically motivated, as one member of the tax commission had already known about the Sadlo loan years prior to the 1954 accusation.[36]

In December 1955, judge Merwyn H. Brown ruled in favor of the Thunderbird and issued a permanent injunction against the tax commission, while stating that the commission should create and publish clear guidelines declaring what is required by casino licensees. He stated that any licensee "is surely entitled to know what is expected of him under the license obtained, and not be subject to annihilation upon an order of the commission based upon no substantial evidence in support of an alleged violation." Brown wrote that the tax commission exhibited an "unusual eagerness" to find wrongdoing against Hicks. He also cited a lack of evidence that Jones had any knowledge of the Sadlo loan.[37][38][39]

Three months later, the tax commission filed a notice of appeal to the Supreme Court of Nevada.[40] Both sides gave briefs to the supreme court at the end of 1956,[41][42][43][44] and final arguments over the injunction were given several months later.[45][39][46] In May 1957, the Nevada supreme court ruled that there was not sufficient evidence to revoke the Thunderbird gaming license. The court also ruled that Brown had acted in error, stating that casino owners shall not be entitled to continue operations under a district court injunction while they are appealing decisions by the tax commission.[47][48][49] The commission chose not to pursue the matter any further.[50][51]

Changes

editJones disposed of his gaming license in 1958, after purchasing a controlling interest in a Haitian casino. The tax commission had adopted a new regulation that prohibited Nevada gaming operators from owning interest in out-of-state casinos. Although Jones was no longer involved in the Thunderbird's gaming operations, he still maintained his ownership stake in the resort.[52][53] The casino was closed in December 1960, for remodeling.[54]

In May 1961, a group of businessmen agreed to lease the Thunderbird from Hicks after he was hospitalized.[55][56][57][58] Hicks had been battling cancer for two years and owned 72 percent of the Thunderbird stock.[2] The new group included Sid Wyman and two other men who had all previously been involved with the Riviera resort nearby.[59] Plans to lease the Thunderbird were canceled in August 1961, as Hicks regained his health and wanted to maintain his control of the resort.[60] He died the following month, at the age of 57.[2] The casino was closed for seven hours so employees could attend Hicks' funeral, marking the second time it had ever been closed.[54] Wells was named as the resort's new managing director, taking over for Hicks.[4] Under Wells, the Thunderbird became heavily affiliated with sporting events such as wrestling and boxing. It also sponsored a deer-hunting contest.[61]

Ground was broken on November 23, 1962, for a $1 million, four-story hotel addition, located directly east of the resort. It was the third phase of a $6 million project to expand and modernize the Thunderbird.[62][63] At the time, the resort also operated 88 rooms at its Thunderbird West building, located on the El Rancho Vegas property and leased to the Thunderbird.[64][65] Big Joe's Oyster Bar opened several months later; it resembled the interior of a ship, and fresh oysters were flown in to the restaurant daily from New Orleans.[66] The four-story addition, with 205 rooms, was opened in November 1963.[67] The expansion project was also supposed to include a skyscraper hotel building, approximately 17 stories with 350 rooms, to be built on the site of the hotel's pool area. It was to open in 1964,[68][62] but it never materialized.

Wells was the president of the Nevada Racing Association.[11] In 1962, he began operating the Thunderbird Speedway in Henderson, Nevada, a city located southeast of the resort. It held auto races for the next two years,[69][70][71] and Wells wanted the Thunderbird hotel to serve as the lodging headquarters for racers.[72] Wells also had plans to construct a Quarter Horse race track directly behind the Thunderbird.[73] The track, known as Thunderbird Downs, opened in October 1963.[74][75][76][77][78] It consisted of a three-eighths mile track,[79] operated along Paradise Valley Road. It was successful, prompting relocation to a larger site in 1964. The new Thunderbird Downs was situated across the street, on property owned by Joe W. Brown that was previously used for the Las Vegas Park.[80][81][82][83][84] In 1965, the Brown family sold the land.[85][86] The Thunderbird Downs track was closed that November,[87] and was demolished in early 1966, replaced by the Las Vegas Country Club.[88] Thunderbird Downs was successful during its two-year run.[3][89][90][91]

Del Webb

editIn September 1964, the Del E. Webb Corporation announced plans to purchase the Thunderbird from Wells and Jones through its subsidiary, Sahara-Nevada Corporation, which owned the nearby Sahara resort.[92][93] The sale price was $9.5 million,[94] and the purchase was approved by the state in January 1965.[95][96] Two months later, plans were announced for a $1.5 million renovation that would include alterations to the facade. One of the Thunderbird statues was replaced by a larger version, and 400 feet of neon signage was added across the front of the building, spelling out the "Thunderbird" name with letters standing two stories tall. The renovation project also included the expansion of the casino, restaurants, and shops, and the construction of an Olympic-size swimming pool. Del E. Webb Construction Company handled the renovations, and Martin Stern Jr. was the architect.[97][98][99][100] The new pool was the largest in Nevada, containing 360,000 gallons of water.[6][101] The Thunderbird's convention and hotel facilities often handled overflow customers from the Sahara resort.[102]

During 1965, a minority stockholder in the Thunderbird sued Wells, Jones, and others over a dispute regarding the Del Webb purchase.[94][103] In 1966, Tom Hanley's union organization, the American Federation of Gaming and Casino Employes, alleged that Sahara and Thunderbird workers were harassed by management after trying to organize into a union.[104] Table game dealers also filed a $100,000 lawsuit against the Thunderbird, alleging that the resort refused to pay them overtime wages.[105] Picketing also took place in front of the Thunderbird, accusing the resort of antisemitism after the firing of a Jewish table game dealer, Howard Bock. Consolidated Casinos Corporation said Bock was fired because he dumped food on another dealer's head. Hanley alleged that Bock was fired because he was Jewish, and said that Bock was harassed by the other dealer because of his ethnicity. Hanley's attempt to unionize the Thunderbird and other casinos was defeated later in 1966, during a National Labor Relations Board election.[106][107]

Business at the Thunderbird decreased following the Del Webb purchase and subsequent sales.[108] In January 1967, Del Webb announced the sale of the Thunderbird for $13 million, to a group of businessmen known as Lance Inc.[109] The state approved the sale three months later.[110][111] At the end of 1967, Lance Inc. defaulted on its payments to Del Webb, and Consolidated Casinos was granted temporary approval by the state to take over the Thunderbird.[112][113][114] In January 1968, Lance Inc. sought refinancing to take over the Thunderbird once again.[115] The company owed an estimated $10 million to $14 million in debt,[116] and a payment plan for its creditors was submitted.[117] However, later that year, the company lost its battle to regain control of the Thunderbird, leaving it in Del Webb's ownership.[118]

Caesars World

editIn July 1972, it was announced that Del Webb would sell the Thunderbird and surrounding acreage for $13.5 million to Caesars World, owner of the Caesars Palace resort on the Las Vegas Strip.[119] The sale was approved later that year.[120][121] Caesars World planned to build a new resort, the Mark Anthony, on the newly acquired property. The project was named after the Roman politician and general Mark Antony, and the resort would have served as a companion to Caesars Palace.[122][123] The Mark Anthony would include a 2,000-room hotel, a casino, and a shopping complex.[121][124] The Thunderbird would continue operations until the near-completion of the Mark Anthony.[121] At the end of 1972, Caesars World planned approximately $500,000 in renovation work for the Thunderbird, believing it could bring in a profit before its planned demolition about two years later.[125] The Thunderbird was operated by a Caesars World subsidiary called Paradise Road Hotel Corporation.[126] After a global search, Caesars World was unable to find financing for the $150 million Mark Anthony project, and its cancellation was announced in June 1975. Caesars World initially stated that there was no intention of selling the Thunderbird, and that there were several plans in consideration for the property.[122][123][127]

In 1976, Caesars World announced that it would sell the Thunderbird for $9 million to Tiger Investment Company, a group of Las Vegas bankers that included E. Parry Thomas. At the time, the hotel had 460 rooms.[128][129][130][131] Joan Louise Siegel, a Las Vegas resident, filed a suit to block the sale. During 1975, she had made two offers to purchase the Thunderbird for $20 million, but was told that the resort was not for sale.[132] A district court judge dismissed the suit, stating that Caesars World had no obligation to sell the resort to Siegel.[133] Tiger Investment completed its purchase later in 1976.[130] The sale agreement involved a leaseback, in which Caesars World continued to operate the resort while it was owned by Tiger Investment.[129][130] The Thunderbird had presented Caesars World with significant financial losses.[134]

Silverbird (1977–82)

editIn December 1976, Major Riddle planned to take over operations at the Thunderbird and rename it as the Silver Bird (later spelled "Silverbird"[135]), consistent with two other casinos he owned in Las Vegas: the Silver Nugget and the Silver City Casino.[130] At the time, the Thunderbird employed 500 people.[136] Riddle planned a renovation of the resort,[137] and had initially wanted to close the casino for the remodeling, before deciding to keep it open.[138] The casino would be enlarged from 18,000 sq ft (1,700 m2) to 53,000 sq ft (4,900 m2), and a sportsbook would be added. A high-rise hotel building had also been planned,[137][139][140] along with the enlargement of the coffee shop and keno lounge. Riddle's target clientele included local residents and tourists both looking for cheap food and "loose" slots.[108][141] Riddle believed that the local market had been forgotten over the years as the Thunderbird continued to change ownership.[137]

The name change took effect on January 1, 1977,[138][108][142] and the property's roadside sign would be updated to reflect the new name, before being replaced entirely with a new sign the following year.[143][144] Riddle changed the name of the resort because he believed that "Thunderbird" had become synonymous with "poor food and tight slot machines."[139] Riddle leased the Silverbird from Tiger Investment, and operated it through his company, NLV Corporation.[145][146][147] The renovation and expansion project took place throughout 1977. The expansion included a new 500-seat buffet, one of the largest in Las Vegas. Joe's Oyster Bar was also expanded, and the resort's showroom was renovated as well. Fifty-five hotel rooms were demolished to make room for the casino expansion, and other rooms were renovated.[145] The hotel was reduced to 385 rooms.[146]

In August 1977, a fire occurred in the hotel's four-story building, forcing the evacuation of its guests. A cigarette had been left behind by hotel guests in a second-floor room, catching a mattress on fire.[148] The Silverbird suffered a two-alarm fire on March 3, 1981, when an arsonist lit up a dressing room under the showroom stage.[149][150] The hotel was evacuated with no injuries, and only minimal damage was caused. However, 14 fire trucks responded because it was the third fire in four months to occur at local resorts.[150]

Riddle died in 1980, and the Silverbird, along with his other casinos, was placed into his estate.[151] The casinos filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy later that year,[152] and a reorganization effort failed to pay off the resort's creditors. An auction of the Silverbird lease was held on December 2, 1981, with a minimum bid of $3.8 million. The resort was worth approximately $2.5 million. Tiger Investment still owned the resort, and any new lessee would have to make monthly payments of approximately $264,000. Other lease expenditures for furniture and equipment would raise the monthly costs to approximately $500,000. Bob Stupak was among those who bid on the Silverbird, but no one bid the minimum amount. Eddy King, the chairman of record promotion company Star Makers Unlimited, offered the highest bid at $3.5 million.[146] Last-minute efforts to negotiate a deal with King did not work out. As a result of the failed auction, the Silverbird was closed on December 3, 1981, at the order of a federal bankruptcy judge. The closure affected approximately 850 employees.[147][153]

El Rancho (1982–92)

editTwo weeks after its closure, Ed Torres announced plans to purchase the Silverbird and its property from Tiger Investment.[154][155][135] He intended to renovate the resort and reopen it by May 1982, and planned to add a hotel tower. Torres was the owner of the Aladdin hotel-casino on the Las Vegas Strip,[154] and was also the father of swimmer Dara Torres.[156][157] Ed Torres knew notorious crime members such as Meyer Lansky and Vincent Alo, but this did not restrict him from acquiring a gaming license for the Silverbird property.[158][159]

Torres' $25 million purchase was approved by the Nevada Gaming Commission in April 1982.[158] Torres spent another $25 million to renovate the property before reopening it as the El Rancho on August 31, 1982. More than 1,000 people attended the opening. The resort was named after the original El Rancho Vegas. Like the earlier resort, the new El Rancho featured a western theme, including a facade of old-western town buildings.[160][161][162] The new resort had a wooden interior accompanied by American Indian items, chandeliers, buffalo trophy heads, and western paintings.[162]

Torres also added a 52-lane bowling alley.[163][164] The western theme and bowling alley were part of an effort to attract families, a growing tourist demographic in Las Vegas.[165] A new poker parlor was also added,[166] but the planned hotel tower did not begin construction until several years later.[167] The renovated resort was again designed by Stern,[168] and it employed 1,400 people.[169] The resort's 13-story hotel tower began construction in 1987, and was completed the following year, adding 580 rooms.[167][170][171][172]

The El Rancho struggled in its final years because of the early 1990s recession, as well as competition from newly opened mega resorts in Las Vegas,[173] specifically The Mirage (1989) and the Excalibur (1990). The latter took away some of the middle-class gamblers that the El Rancho had relied upon.[174] Torres announced in May 1992 that the resort would close in two months, giving workers a mandated 60-day notice. At the time, Torres had been trying to sell the resort for $25–30 million, but was unsuccessful. The closure announcement came after the Culinary Workers Union voted against Torres' request for concessions.[175][173] The El Rancho also owed gaming taxes for its 918 slot machines.[176]

The bowling alley, sportsbook, and slot machines were shut down on June 30, 1992,[173] and the rest of the resort ceased operations on July 6, 1992.[173][174][175] The closure affected 324 employees. Workers blamed Torres for the closure, stating that there were years of disinterest and lack of promotion on his part.[173] At the time of its closure, the El Rancho occupied 20 acres.[175] It had a 90,000 sq ft (8,400 m2) casino,[177] 1,007 hotel rooms,[173] and four restaurants.[177] The adjacent Algiers Hotel continued to operate for the next 12 years.[178]

Failed projects (1992–99)

editBy August 1993,[179][180] Las Vegas Entertainment Network Inc. (LVEN), a Los Angeles-based television production company, had plans to redevelop the resort and reopen it in 1994 as El Rancho's Countryland USA. The new resort would have included a family-oriented theme park with country-style entertainment and attractions. LVEN also planned to construct two 20-story hotel towers meant to resemble a gigantic pair of Western-style boots. The new towers would have brought the El Rancho up to a total of 2,001 hotel rooms.[181] Harry Wald, the former president and chief operating officer of Caesars Palace, was to direct the redevelopment of the El Rancho into a full-time family resort.[182][183] LVEN purchased the property in November 1993,[184] for $36.5 million.[185]

By January 1994, LVEN planned to open El Rancho's Countryland USA with its own 24-hour cable television channel based inside the new resort, which would have housed facilities for production and broadcasting. The channel would have promoted events at Countryland USA, as well as other resorts. LVEN also planned to add a country-themed shopping mall and a rodeo production facility to the new resort.[186] Construction of the new hotel towers was delayed because of a lack of financing. In October 1994, LVEN received $35 million from a Dallas investment bank for construction of the towers. At that time, LVEN also planned to launch the Las Vegas Country Television Network, which would have featured country-western entertainment and other shows on the Las Vegas Strip.[187]

In January 1996,[188] Orion Casino Corporation purchased the El Rancho from LVEN for $43.5 million. Orion Casino Corporation was a newly formed Nevada subsidiary of International Thoroughbred Breeders (ITB), a New Jersey racetrack operator founded by Robert E. Brennan, who had previously organized a penny stock scheme.[189] A month after the purchase, ITB announced plans to demolish the El Rancho and construct Starship Orion, a $1 billion hotel, casino, entertainment and retail complex with an outer space theme, covering 5.4 million square feet. The resort was to include seven separately owned casinos, with each one being approximately 30,000 sq ft (2,800 m2).[189] Individual partners would each contribute up to $100 million to own and operate a casino within the complex.[190] Orion Casino Corporation would own and operate one of the seven casinos.[191] The complex would include 300,000 sq ft (28,000 m2) of retail space, as well as 2,400 hotel rooms and a 65-story hotel tower. ITB hoped to begin construction later in 1996, with a planned opening date of April 1998. Some gaming analysts expressed skepticism that the Starship Orion project could get built, citing the high cost and ITB's lack of casino experience.[189]

In an agreement with LVEN, ITB was to come up with financing for Starship Orion, with a deadline of October 25, 1996. If ITB were unsuccessful, LVEN had an option to seek alternative financing for a less-expensive project, such as re-opening the El Rancho. A week before the deadline, ITB told LVEN that the Starship Orion project had not generated any financing from potential investors. ITB was pursuing other possible options for the property at that time. ITB and LVEN subsequently got into a dispute regarding control of the El Rancho.[192] In addition, Brennan was ordered by the New Jersey Casino Control Commission to sell his shares of ITB, as he had been fined $71.5 million for securities fraud in 1995.[193]

In January 1997, Brennan sold his interest in ITB to New Mexico businessman Nunzio DeSantis and former politician Tony Coelho, who were unable to make any progress on plans for the property.[194][193][195][159] ITB had plans for a $100 million renovation of the El Rancho, which they planned to reopen as Countryland USA. The new resort would have included a 1,700-room hotel and a 100,000 sq ft (9,300 m2) casino.[193] In February 1997, ITB and LVEN settled their dispute, while the resort was expected to reopen in the first quarter of 1998.[188][194] However, Coelho and DeSantis feuded with ITB board members who allegedly were trying to help Brennan retain control of the company. SunAmerica, the prospective underwriter for Countryland USA, subsequently chose not to proceed with its $100 million investment, out of concerns over the project and management.[195] Ultimately, ITB stated that it was unable to raise financing for Countryland USA.[196]

At the end of 1997, Turnberry Associates purchased the 15-acre parcel behind the El Rancho, where Thunderbird Downs had previously operated.[197] The company began developing the Turnberry Place condominium towers on the site, located directly east of the El Rancho.[198] By June 1999, a partner company of LVEN was considering a purchase of the El Rancho, with plans to renovate it at a cost of $354 million.[185][199][200] Ultimately, the sale did not proceed.[198]

Investigation and demolition (1999–2000)

editIn the years that it sat vacant, the El Rancho had come to be widely considered as the city's worst eyesore.[201] In 1999, local news channel KVBC News 3 was granted access to the El Rancho after being invited by two unnamed workers. KVBC conducted and aired an investigation of the resort's structures. Asbestos and exposed wiring were found throughout the buildings, as well as corroding chemicals which covered the floors. Rats and bugs were found to be inhabiting the resort. Homeless people had also been sneaking inside the closed resort and staying there, and marijuana and empty beer bottles were discovered by the news team.[202][196][203][204] While most of the structures were decomposing, another section of the El Rancho was found to have been renovated with working slot machines, which had been lent to the owners by Bally Gaming three years earlier to showcase to potential investors for the Countryland USA project. After the investigation aired, the property's owners were fined for health and safety violations by the local building and fire departments, as well as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.[202][196][203] In addition, LVEN was subsequently investigated by the FBI and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for alleged stock scams and investor fraud.[196]

In February 2000, Turnberry Associates acquired a six-month option to purchase the El Rancho from ITB.[198] Two months later, Turnberry agreed to the purchase with plans to demolish the El Rancho.[205] Turnberry considered the resort an eyesore and wanted to remove it for future residents of Turnberry Place ahead of its opening.[198][206] The sale was finalized in May 2000,[184][207] at a cost of $45 million.[208] Turnberry considered eventually building a hotel-casino or timeshares on the El Rancho property.[207]

A sale of the El Rancho's contents was held beginning on June 1, 2000, but was initially restricted to the first two floors because of safety concerns regarding other areas of the resort.[209][210] Much clean-up work had to be done to the resort to prepare it for the sale, removing dust and disrepair.[211] Among the items for sale were furnishings, bathroom fixtures, and carpeting. The bowling alley was also for sale, at a cost of $114,000.[209][210] Other items for sale included 900 televisions and full-sized horse replicas. Gaming equipment was not part of the sale, having been removed by ITB prior to the Turnberry purchase.[211][212]

On October 3, 2000, the resort's last remaining structure, the 13-story hotel tower, was imploded with 700 pounds of dynamite. The implosion took place at 2:30 a.m., and more than 2,000 spectators came to witness it.[162][213][214] For safety reasons, the demolition was a subdued event compared to past implosions in Las Vegas. Turnberry had given only minimal publicity to the implosion, in order to minimize the number of spectators.[215][216][213] Police officers were brought on to keep crowds at a safe distance.[162][206] The Algiers Hotel was covered in plastic to protect it against dust from the implosion,[213] and it did not have any hotel guests at the time.[162]

Site cleanup for the demolition debris was expected to take two months.[206] Approximately 10,000 pounds of concrete from the demolished resort was used by the Southern Nevada Water Authority and the Las Vegas Wash Coordination Committee to stabilize the Las Vegas Wash.[15][217][218] The El Rancho's implosion was recorded and featured in the 2004 National Geographic Channel documentary Exploding Las Vegas, along with several other Las Vegas casino implosions.[219]

Turnberry initially planned to build a London-themed resort on the El Rancho land,[220] but the project was later canceled. The site of the El Rancho and Algiers was later used for the Fontainebleau Las Vegas resort, which began construction in 2007.[221][222][223] The resort opened on December 13, 2023, following construction delays.[224][225]

Entertainers

editPatti Page's first Las Vegas performance took place at the Thunderbird in 1948.[226] Nat King Cole was also a frequent entertainer at the Thunderbird.[11] Other notable performers included Donald O'Connor, Mel Tormé, Rosemary Clooney,[227] James Melton,[228] Bunny Briggs,[229] Rex Allen,[11][230] Henny Youngman,[227][231] Margaret Whiting, Peggy Lee,[232] and Judy Garland.[232][233] Two albums were recorded at the Thunderbird and were released in 1963: Caught in the Act, Vol. 2 by Frances Faye,[234] and At The Las Vegas Thunderbird by Gloria Lynne.[235]

The Thunderbird offered numerous shows throughout its history. In the late 1950s, The Kim Sisters were among 35 cast members who performed in the resort's China Doll Revue.[236][237][238] In 1959, the Thunderbird launched a partially nude ice show known as Ecstasy on Ice.[239][240][241] Flower Drum Song opened in December 1961, and proved to be a success.[242] The show was initially only signed for a few weeks, but ultimately ran for nearly a year before being replaced by South Pacific.[242][243][244] Flower Drum Song had attracted more than 360,000 people over the course of its run,[244] and South Pacific was also well received.[245][244]

South Pacific closed in 1963, and was replaced by a summer engagement of Flower Drum Song, marking its return to the Thunderbird theatre.[246] The show's run was again extended, until the end of 1963,[247] followed by the launch of Ziegfeld Follies in 1964.[248][249] Two years later, the resort's Continental Theatre hosted Bottoms Up, becoming the only afternoon entertainment on the Las Vegas Strip.[250][251] The Thunderbird later hosted Thoroughly Modern Minsky, a show by Harold Minsky.[240][252] Flower Drum Song returned for a third run in 1969.[253][254]

In 1972, the Thunderbird launched Geisha'rella, a topless revue of Japanese women.[238][255] In the mid-1970s, the resort hosted entertainers such as Cyd Charisse, Keely Smith, and Tony Martin.[241] Redd Foxx was also a frequent performer, and he held his third wedding at the resort in 1976.[232][256][257] A year later, the Silverbird launched a show titled Playgirls on Ice '77.[258] The Continental Theatre had seating for 620 people at the time.[232]

Ipi Tombi, a South African show, debuted at the Silverbird in 1979, but ended due to lack of popularity.[259] In 1981, the financially struggling resort launched a show titled Feminine Touch.[259][260] In 1990, Rodney Dangerfield opened a comedy club at the El Rancho known as Rodney's Place, which previously had an unsuccessful run at the Tropicana resort. The club presented a variety of comedians.[261][262][263] It closed a year later, due to poor business.[264]

References

edit- ^ a b c Ainlay, Thomas; Gabaldon, Judy Dixon (2003). Las Vegas: The Fabulous First Century. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 102, 133. ISBN 978-0-7385-2416-0. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Marion Hicks Clark Casino Owner Passes". Associated Press. September 11, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Juipe, Dean (April 30, 2004). "Tapit gives Las Vegas a Derby connection". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Thunderbird Director Elected". Associated Press. September 15, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "To Build Hotel". Nevada State Journal. March 18, 1946. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Goertler, Pam (Summer 2007). "The Las Vegas Strip: The early years" (PDF). Casino Chip and Token News. pp. 36–38. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Construction Started On New Resort Hotel South of Las Vegas". Las Vegas Review-Journal. October 28, 1947. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "Thunderbird Hotel Has Gala Opening". Las Vegas Review-Journal. September 5, 1948. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "Las Vegas Hotel Opening Slated". Reno Evening Gazette. August 31, 1948. Retrieved June 18, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Las Vegas Neon Sign Co., Will Erect Spectacular Display". The Deseret News. August 27, 1948. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Cantarini, Martha Crawford; Spicer, Chrystopher J. (2014). Fall Girl: My Life as a Western Stunt Double. McFarland. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7864-5597-3. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Mitchell (November 15, 2019). "Lost Signs of Las Vegas—Part 1". Neon Museum. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Zook, Lynn M.; Sandquist, Allen; Burke, Carey (2009). Las Vegas, 1905-1965. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 78, 101. ISBN 978-0-7385-6969-7. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Las Vegas Hotels Plan Expansion". Reno Evening Gazette. February 17, 1949. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Thunderbird history". A2ZLasVegas.com. Archived from the original on 2001-02-01.

- ^ Delaney, Joe (October 5, 2000). "Memories and dust all that are left of El Rancho". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Adonis' Buddies Alleged Partners Of Cliff Jones". Nevada State Journal. October 13, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russell Vs. Pittman Race Is Nip and Tuck". Nevada State Journal. October 21, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charge is Made". Reno Evening Gazette. November 24, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Game Probe Ends First Phase (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 27, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Game Probe Ends First Phase (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 27, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Commission Airs Jones Case Today". Nevada State Journal. October 26, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Hotel Told to Show Cause". Nevada State Journal. December 2, 1954. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Witnesses Face Questions in Probe of Hotels". Reno Evening Gazette. January 7, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tax Commission Waits To Hear Sadlo's Story". Nevada State Journal. January 23, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Lansky Is Paid By Thunderbird (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. March 1, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lansky Is Paid By Thunderbird (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. March 1, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Tax Board Ousts Gamblers". Reno Evening Gazette. April 2, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tax Board Ousts Jones, Hicks". Nevada State Journal. April 2, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Texans Offer To Lease Big Hotel At Vegas". Nevada State Journal. May 4, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hotel Thunderbird's Deadline Is Nearing". Nevada State Journal. May 13, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Sues State Tax Board". Reno Evening Gazette. May 19, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ousted Owners Of Vegas Hotel Get Injunction". Nevada State Journal. May 20, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Wins First Court Test". Reno Evening Gazette. June 24, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Blakey Says 'Evil' Tax Commission Persecuted Hicks and Jones". Nevada State Journal. October 19, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Retrieved July 26, 2020:

- "Tax Chief Admits He Knew of Loan; Deposition Taken From Cahill After State Loses Court Round". Reno Evening Gazette. September 30, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Cahill Admits Knowing About Loan to Hotel". Nevada State Journal. October 1, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gaming Control Board Will Meet; Thunderbird Attorneys Will Ask To Question Investigation Staff". Reno Evening Gazette. October 5, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Round Won by Thunderbird; Cahill Takes Stand As Hearing Opened (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 17, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Round Won by Thunderbird; Cahill Takes Stand As Hearing Opened (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 17, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Thunderbird Case Called Political Weapon; Judge Studies Injunction for Hicks, Jones (page 1 of 2)". Nevada State Journal. October 20, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Thunderbird Case Called Political Weapon; Judge Studies Injunction for Hicks, Jones (page 2 of 2)". Nevada State Journal. October 20, 1955 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Wins in Court; Hicks, Jones License Action is Reversed (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. December 19, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Wins in Court; Hicks, Jones License Action is Reversed (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. December 19, 1955. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Gaming Issue in High Court (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. March 30, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Notice Filed In Thunderbird License Case". Nevada State Journal. March 17, 1956. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brief Answered By Thunderbird (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 22, 1956. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brief Answered By Thunderbird (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. October 22, 1956. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Final Brief In Thunderbird Case on File (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. November 16, 1956. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Final Brief In Thunderbird Case on File (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. November 16, 1956. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Attorneys Argue Thunderbird Writ". United Press. March 30, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gaming Issue in High Court (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. March 30, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Case Won by Thunderbird (page 1 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. May 3, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Case Won by Thunderbird (page 2 of 2)". Reno Evening Gazette. May 3, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lower Court Gaming Writs Termed Error". United Press. May 4, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Battle Ends After Ruling". United Press. May 28, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Case Closed By Tax Board". Reno Evening Gazette. May 28, 1957. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jones, Kozloff in Haiti Casino". Reno Evening Gazette. December 27, 1958. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cliff Jones 'Finally' Out of Gaming". Nevada State Journal. October 4, 1964. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Casino Quiet; Services Held For Its Owner". Associated Press. September 14, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Loew Interested In Thunderbird". Reno Evening Gazette. May 15, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gaming Strip Hotel Leased". Reno Evening Gazette. May 29, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gaming Conflict Brings Decision". Reno Evening Gazette. June 20, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State Gaming Control Board Delays Action on Thunderbird". Reno Evenming Gazette. July 19, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hotel Purchase Talks Continue". Reno Evening Gazette. May 10, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Resort Hotel Lease Proposal Dropped in Clark". Associated Press. August 7, 1961. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "T-Bird Will Sponsor Deer Hunting Contest". Las Vegas Sun. June 6, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Ground Broken at Site Of Thunderbird Project". Las Vegas Sun. November 24, 1962. pp. 1–2. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "T-Bird Hotel Prepares To Roll Out The Red Carpet". Henderson Home News. July 19, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Will Build $6 Million Skyscraper". Henderson Home News. October 11, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "News". Las Vegas Sun. May 11, 1963. Retrieved September 30, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Oyster Bar Adds to T-Bird". Las Vegas Sun. March 3, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Opens New Addition". Las Vegas Sun. November 17, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Hotel Announces Skyscraper Plan". Associated Press. October 4, 1962. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wells Lists Plans to Promote Track". Las Vegas Sun. April 25, 1962. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Question of the Day". Las Vegas Advisor. November 5, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Cannon, Randall; Gerry, Michael (2018). Stardust International Raceway: Motorsports Meets the Mob in Vegas, 1965-1971. McFarland. pp. 123–145. ISBN 978-1-4766-7389-9. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Joe Wells Would Give City Airport for Speedway Control; Official Track Name of T-Bird Speedway OK'd". Henderson Home News. April 24, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Sports". Las Vegas Sun. May 27, 1962. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "New T-Bird Track Rated Among Best in West". Las Vegas Sun. September 18, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Downs Set for Opening". Las Vegas Sun. September 29, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Top Moon Takes T-Bird Feature". United Press International. October 6, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Horse Racing In Las Vegas". Progress-Bulletin. October 16, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "From the Tower". Las Vegas Sun. November 8, 1963. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Contest Opens to Name New Race Track For Vegas Valley Area". Henderson Home News. November 23, 1965. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Top Sports Cards Set For T-Bird". Las Vegas Sun. August 16, 1964. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Downs". Las Vegas Sun. March 8, 1964. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "T-Bird Downs' New Home". Las Vegas Sun. April 25, 1964. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Fast Track Seen For Race Season". Las Vegas Sun. September 16, 1964. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Question of the Day". Las Vegas Advisor. January 22, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "News". Las Vegas Sun. July 14, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Gigantic Plans to Develop Joe Brown Property". Las Vegas Sun. August 5, 1965. pp. 1–2. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "T-Bird Downs Closes". Las Vegas Sun. November 23, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Wade, Dell (April 10, 1966). "Parade of Progress". Las Vegas Sun – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Downs Fans Betting More In '64". Henderson Home News. November 12, 1964. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Nationally Famed Jockeys To Ride At T-Bird Downs". Henderson Home News. November 19, 1964. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Developers Wager on Rebirth of Old Track". Nevada State Journal. January 26, 1976. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "State's Okay Next in T-Bird Sale". Las Vegas Sun. September 19, 1964. pp. 1–2. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Hotel Webb's Newest Nevada Property" (PDF). The Webb Spinner. October 1964. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "Casino Sale Subject of Vegas Suit". Reno Evening Gazette. June 4, 1965. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Gaming Board Holds Up Tally Ho Opening; Okay Sale Of T-Bird To Webb". Las Vegas Sun. January 19, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Sale to Webb Wins Approval". Associated Press. January 20, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Look for Thunderbird Hotel: $1 ½ Million Facial". Las Vegas Sun. March 7, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Nevada Real Estatemints". Las Vegas Sun. May 23, 1965. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Building OK". Las Vegas Sun. July 21, 1965. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird 'Sporting' Stunning New Facade" (PDF). The Webb Spinner. September 1965. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Thunderbird advertisement". Las Vegas Sun. September 2, 1966. Retrieved July 26, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Hotel Sales Staff Job: 'Keep Our Rooms Full'" (PDF). The Webb Spinner. October 1969. pp. 1, 4–5. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "Suit Over T-Bird Sale Was a Surprise-Jones". Las Vegas Sun. June 5, 1965. pp. 1–2. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Union-Webb Casinos End Testimony Today". Las Vegas Sun. April 15, 1966. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Dealers Suing Casino". Las Vegas Sun. April 23, 1966. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Casino Union 'Stomped': Humiliating Loss at Mint, Lucky Clubs". Las Vegas Sun. July 29, 1966. pp. 1–2. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Judge Allows 10 Days for Briefs – T-Bird, Gaming Union Case Nears End". Las Vegas Sun. August 3, 1966. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Temporary T-bird License Stalls Major Riddle's Plans". Las Vegas Sun. December 30, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Hotel Sold In Las Vegas". Associated Press. January 14, 1967. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird License Recommended". Associated Press. April 26, 1967. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Nevada OKs Sale of Vegas Hotel for $13 Million". United Press International. April 30, 1967. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hughes, Webb Win Approval to Extend Las Vegas Casino Holdings". Reno Evening Gazette. December 20, 1967. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Casino Licenses For Del Webb, Howard Hughes". Associated Press. December 29, 1967. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "T'bird Gets Temporary Licensing". Las Vegas Sun. January 11, 1968. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Dateline: Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun. January 7, 1968. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "T'bird Foreclosure Ruling Due Monday". Las Vegas Sun. June 13, 1968. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Lance Asks Okay To Run Thunderbird Hotel Again". Las Vegas Sun. May 3, 1968. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Lance Loses Court Fight; Webb To Keep T-Bird Hotel". Las Vegas Sun. June 19, 1968. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird Hotel sold in Las Vegas". Associated Press. July 22, 1972. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Miami Group To Buy Las Vegas Hotel". Orlando Sentinel. October 20, 1972. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Caesars World closes hotel deal". Miami News. November 1, 1972. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Caesars World Kills Off Plan for Mark Anthony (page 1 of 2)". Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1975. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Caesars World Kills Off Plan for Mark Anthony (page 2 of 2)". Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1975. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Construction Plans Top Billion-Dollar Mark". The Hartford Courant. September 3, 1972. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fix It Up --- Tear It Down". Des Moines Register. December 26, 1972. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thunderbird named in junket rule complaint". Associated Press. November 16, 1973. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Las Vegas hotel plan canceled". Press-Courier. Oxnard. Associated Press. June 12, 1975. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "To Las Vegas Banking Group: Thunderbird Hotel-Casino Sale Near". Las Vegas Sun. August 23, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "For $9 Mil. To Las Vegas Bankers: Caesars World Confirms Sale Of Thunderbird". Las Vegas Sun. September 15, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c d "Major Riddle Will Buy T'Bird". Las Vegas Sun. December 9, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Large motel sold at loss". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. 16 September 1976. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ "T'bird Sale Suit Filed". Las Vegas Sun. October 15, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Judge Kills Suit To Block T-Bird Sale". Las Vegas Sun. October 20, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Caesars World Record Quarter". Las Vegas Sun. December 11, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Silverbird hearing set". Reno Evening Gazette. Associated Press. March 31, 1982. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dateline: Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun. December 22, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Thunderbird now the Silver Bird". Reno Gazette-Journal. AP. January 5, 1977 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Special Gamers Meeting". United Press International. December 23, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Major Riddle Announces Silver Bird Plans". Las Vegas Sun. January 5, 1977. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Silverbird Hotel". Henderson Home News. January 6, 1977. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Major Riddle Approved – County Okays T'bird Switch". Las Vegas Sun. December 31, 1976. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Butler Leads Silver Bird". Las Vegas Sun. January 27, 1977. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Silver Bird hotel to have tallest free-standing sign". Las Vegas Review-Journal. January 5, 1978. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "The Old and the New". Las Vegas Review-Journal. March 29, 1978. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Wade, Dell (June 2, 1977). "The Silver Bird – Casino Gets Plumage". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Auction For Silverbird Hotel Fizzles". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Associated Press. December 3, 1981. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Vegas Hotel To Go Down Next Month". Daily Herald. United Press International. December 13, 1981. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Silver Bird Guests Routed By Blaze". Las Vegas Sun. August 9, 1977. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Gambler and Guests Evacuated as Fire Hits Hotel in Las Vegas". Muncie News. March 4, 1981.

- ^ a b "Fire forces 1,000 to flee hotel in Las Vegas; Arson is blamed". Arizona Republic. March 4, 1981.

- ^ "Control board recommends Silver Bird leader". Reno Evening Gazette. October 16, 1980. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cher's upset". The Desert Sun. October 7, 1980. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Silverbird closes after bailout auction fails". Reno Evening Gazette. Associated Press. December 3, 1981. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Torres plans 700-room addition after Silverbird purchase". Reno Evening Gazette. Associated Press. December 17, 1981. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Torres reaches agreement to buy Silverbird Hotel". The Spectrum. United Press International. December 17, 1981. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Downey, Mike (August 16, 2008). "She's propelled by dad's memory". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Farmer, Jenna (May 12, 2009). "UF grad, Olympian Torres inspires with new book". University of Miami News. Retrieved August 5, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Nevada will allow Torres to buy the bankrupt Silverbird casino". Los Angeles Times. April 7, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Ghosts of El Rancho rise to haunt Gore campaign manager". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Las Vegas Review Journal. December 1, 1999. Archived from the original on 2003-05-08.

- ^ "El Rancho Casino opens today". The Spectrum. United Press International. August 31, 1982. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hotel opens to large crowds". Santa Maria Times. Associated Press. September 1, 1982. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Radke, Jace (October 3, 2000). "Strip says adios to El Rancho". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Hundreds swarm into new El Rancho Hotel Casino". The Spectrum. United Press International. September 1, 1982. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cards, bowling open at El Rancho today". Las Vegas Review-Journal. December 30, 1982. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ Macy, Robert (June 6, 1985). "Vegas casinos court vacationing families: Moving from high rollers to high chairs". Reno Gazette-Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Willard, Bill (January 14, 1983). "Las Vegas Showcase of the Stars". Las Vegas Israelite. p. 11. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Willard, Bill (September 25, 1987). "Las Vegas Showcase of the Stars". Las Vegas Israelite. p. 15. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (August 1, 2001). "Martin Stern Jr.; Architect Shaped Vegas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Macy, Robert (September 2, 1982). "Recession comes to Vegas". Reno Evening Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved August 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "El Rancho addition mulled". Las Vegas Review-Journal. August 22, 1987. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "High-rise addition set for El Rancho". Las Vegas Review-Journal. September 3, 1987. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "Mardian Construction: Building on a Strong Reputation" (PDF). Nevada Business. August 1988. pp. 22–24. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Vegas hotel to close". The Press Democrat. July 1, 1992. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "El Rancho Hotel closes". North County Blade-Citizen. July 7, 1992. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Vegas Strip resort to close down in July". Reno Gazette-Journal. Associated Press. May 7, 1992. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Krane, Elliot S. (July 19, 1992). "El Rancho Refuses to Pay Slot Tax, Closes Its Doors". The Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewsLibrary.

- ^ a b "Group to turn Vegas' El Rancho Hotel & Casino into country-music park". United Press International. August 6, 1993. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "50-Year-Old Algiers Hotel Closes". KLAS. September 2, 2004. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Edwards, John G. (August 6, 1993). "Los Angeles firm signs preliminary agreement to buy El Rancho". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "El Rancho Hotel". Elko Daily Free Press. Associated Press. August 14, 1993. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Handley, John (October 17, 1993). "More Tall Orders". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "California company planning country resort at El Rancho". Reno Gazette-Journal. October 14, 1993. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Krane, Elliot S. (November 14, 1993). "Ex-Caesars Palace Chief Picked to Head El Rancho". The Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewsLibrary.

- ^ a b "Property ownership history". Clark County Assessor's office. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b "Sale possible of old El Rancho on the Strip". Las Vegas Sun. Las Vegas Sun. June 7, 1999. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ^ "Las Vegas Entertainment Network 'El Rancho's Countryland U.S.A.' To Have 24-Hour Cable Television Operation". TheFreeLibrary.com. January 3, 1994. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "A Hee Haw Play In Vegas". Bloomberg Business. October 30, 1994. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b "Firms Settle Dispute, to Build Casino". Los Angeles Times. February 6, 1997. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b c Buntain, Rex (February 22, 1996). "N.J. firm's plans for the El Rancho rapped". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "ITB loaned $30 million for Orion". Las Vegas Sun. June 6, 1996. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ Buntain, Rex (February 21, 1996). "$1 billion resort to rise from El Rancho". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Gary (October 31, 1996). "Starship Orion may not take flight". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b c Mastrull, Diane (January 16, 1997). "Firm Takes Reins At N.j. Track". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ a b Brickley, Peg (October 13, 1997). "Panel queries racetrack practices". Philadelphia Business Journal. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Hosenball, Mark (May 14, 2000). "Gore's Master Dealmaker". Newsweek. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "El Rancho - The Last Las Vegas Mystery". KVBC. April 24, 2000. Archived from the original on June 20, 2003.

- ^ "Turnberry Associates buys parcel owned by ITT Corp". Las Vegas Review-Journal. February 16, 1998. Archived from the original on February 20, 1999.

- ^ a b c d "Developer takes option on shuttered casino". Las Vegas Sun. February 4, 2000. Archived from the original on 2000-08-16.

- ^ Strow, David (July 15, 1999). "Deal could speed El Rancho plans". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "LVEN mum on sale, El Rancho owner's outside auditor quits". Las Vegas Sun. October 1, 1999. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Hubble (October 3, 2000). "Turnberry has casino in mind". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on June 28, 2001.

- ^ a b Spears, Darcy (February 23, 2000). "El Rancho Eyesore". KVBC.

Even OSHA, who had never stepped foot on the property until our investigation aired, cited and fined El Rancho for the very violations we had uncovered. They fined El Rancho especially for the live exposed electrical wires and the corroding chemicals covering some floors. "Unbelievable," said Acosta." One, that the El Rancho was still standing. And two, that those chemicals and the conditions were all still there." The property managers won't let us back in to show you how much has changed, but county officials assure us the place has been cleaned up. "Things were cleaned up beyond his expectations," says Steve Lasky with the Clark County Fire Department.

- ^ a b "Follow-up: El Rancho". KVBC. 2000. Archived from the original on July 1, 2003.

- ^ "Darcy Spears Reports on El Rancho's Legacy". KVBC. October 2, 2000. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Strow, David (April 27, 2000). "Condo developer to buy El Rancho". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Jeff (October 4, 2000). "El Rancho crumbles like clockwork: Developer says he wanted to remove eyesore from Strip". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on June 17, 2001.

- ^ a b "Turnberry sets El Rancho demolition for this fall". Las Vegas Sun. May 24, 2000. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "El Rancho to be demolished". Las Vegas Sun. May 24, 2000. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "El Rancho Auction". KVBC. 2000. Archived from the original on October 11, 2000. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "El Rancho Sale". KLAS-TV. 2000. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000.

- ^ a b Strow, David (June 1, 2000). "Las Vegas-style yard sale under way at El Rancho". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Hubble (June 3, 2000). "Come Sale Away: Bargain hunters scour El Rancho's remains for keepsakes". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on April 16, 2001.

- ^ a b c Snedeker, Lisa (October 3, 2000). "El Rancho implosion marks end of an era". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Curtis, Anthony (October 8, 2000). "Historic El Rancho finally demolished". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Strip hotel implosion set for Oct. 3". Las Vegas Sun. September 26, 2000. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "El Rancho implosion set for Tuesday morning". Las Vegas Sun. September 27, 2000. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Recycling Las Vegas History at the Wash". LVWash.org. Archived from the original on 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "Wash Weir Construction". Southern Nevada Watering Authority. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "National Geographic Channel Takes an Explosive Journey With the 'First Family' of Implosions". PRNewswire. November 15, 2004. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Simpson, Jeff (February 22, 2001). "Commission to hear casino proposals". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on February 20, 2002.

- ^ Stutz, Howard (May 13, 2005). "Back on the Strip: Developer counts on LV touch". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on January 1, 2006.

- ^ Simpson, Jeff (June 10, 2007). "Jeff Simpson on why a new resort positioned in the space formerly occupied by the Thunderbird should make money this time". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Leach, Robin (November 9, 2015). "Caesars to build arena to compete with MGM? Fontainebleau to restart?". Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Ross, McKenna (September 18, 2023). "Fontainebleau sets Las Vegas opening date after 18 years". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ Velotta, Richard N. (December 14, 2023). "Fontainebleau's first guests impressed by casino's art, decor". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ Page, Patti; Press, Skip (2017). This Is My Song: A Memoir. New Word City. ISBN 978-1-64019-087-0. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Remembering old Las Vegas". Las Vegas Sun. December 13, 2002. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "This Smells: Vegas Opening Will Promote New Perfume". Billboard. December 5, 1953. p. 15. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Hill, Constance Valis (2014). Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-022538-4. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Koch, Ed (August 24, 1996). "The singing emcee". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Thunderbird". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. December 25, 1966. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Hanford Searl (January 29, 1977). "Thunderbird Now The Silver Bird". Billboard.

- ^ Schechter, Scott (2006). Judy Garland: The Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Legend. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-4616-3555-0. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Frances Faye Begins Five-Week T-Bird Play". Las Vegas Sun. September 11, 1963. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (October 18, 2013). "Jazz chanteuse Gloria Lynne dies at 83". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Chung, Sue Fawn (2011). The Chinese in Nevada. Arcadia Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7385-7494-3. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Forgotten Femmes, Forgotten War". University of Nevada, Las Vegas. December 18, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Han, Benjamin M. (2020). Beyond the Black and White TV: Asian and Latin American Spectacle in Cold War America. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-0385-5. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Nightclubs: Big Week in Vegas". Time. August 17, 1959. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Gioia-Acres, Lisa (2013). Showgirls of Las Vegas. Arcadia Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7385-9653-2. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b McKay, Janis L. (2016). Played Out on the Strip: The Rise and Fall of Las Vegas Casino Bands. University of Nevada Press. pp. 73, 95–96. ISBN 978-1-943859-03-0. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "'Flower Drum Song' Now In Record 10th Month". Las Vegas Sun. September 22, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'Flower Drum' Starts Final Three Weeks". Las Vegas Sun. November 3, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "News". Las Vegas Sun. February 2, 1963. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'South Pacific' To Set New Records". Las Vegas Sun. December 30, 1962. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Flower Drum Song Returns For Summer Engagement At T-Bird". Henderson Home News. June 20, 1963. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'Flower Drum Song' Returns Soon To Thunderbird Hotel". Las Vegas Sun. August 8, 1969. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Ziegfeld Follies" for Las Vegas Thunderbird". San Mateo Times. July 10, 1964. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ziegfeld Follies". Las Vegas Sun. September 20, 1964. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'Bottoms Up" Show into the T-Bird". Las Vegas Sun. June 11, 1966. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'Bottoms Up' revue comedian Breck Wall dies at 75". Las Vegas Review-Journal. November 16, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Minsky Show To Reopen With New Acts, Stars". Las Vegas Sun. June 17, 1968. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ Pearl, Ralph (August 28, 1969). "'Flower Drum,' Buddy Hackett Crowd-Pleasers". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "'Flower Drum Song' Fills T-Bird Theatre". Las Vegas Sun. August 28, 1969. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "From the Music Capitals of the World". Billboard. December 25, 1971. pp. 18, 27. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Hyman, Harold (January 1, 1977). "'Sanford' Ties Knot At T-Bird". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Foxx Leaves Trail Of Jokes After He Marries In Las Vegas". Jet. Vol. 51, no. 18. January 20, 1977. p. 10.

- ^ "Silver Bird Back In Show Biz With 'Playgirls'". Las Vegas Sun. July 8, 1977. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b Walter, Tim (March 21, 1981). "Productions On Tap At Vegas Silverbird Hotel" (PDF). Billboard. p. 69. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "CaShears gets Vegas debut at Silverbird". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1981. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Can Rodney succeed blocks from where he once failed". Las Vegas Review-Journal. August 5, 1990. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "Rodney's opens at the El Rancho". Los Angeles Times. October 21, 1990. Retrieved August 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weatherford, Mike (March 11, 2009). "The Comedy Stop will stop". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Paskevich, Michael (August 30, 1991). "Rodney's can't get laughs". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2023.