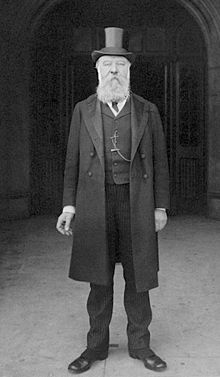

Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence, 1st Baronet (2 February 1837 – 21 April 1914) was a British lawyer and Member of Parliament.

Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence, Bt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Truro | |

| In office 1895–1906 | |

| Preceded by | John Charles Williams |

| Succeeded by | George Hay Morgan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 February 1837 |

| Died | 21 April 1914 (aged 77) |

| Political party | Liberal Unionist |

| Spouse | Edith Jane Smith |

| Occupation | Politician, author |

He is best known for his advocacy of the Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship, which asserts that Francis Bacon was the author of Shakespeare's plays. He published a number of books on the subject and promoted public debates with the academic community. At his death he donated the large "Edwin Durning-Lawrence archive" to London University.

Life

editHe was born Edwin Lawrence, the seventh son and last child of William Lawrence and Jane Clarke. His father, who built up his fortune in construction, held political posts in London. His brothers Sir William Lawrence and Sir James Lawrence were Lord Mayors of London and also members of parliament. His nephew was Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, the suffragette[Footnote 1] and pacifist MP.

Edwin studied law at London University and was admitted to Middle Temple in 1867 as a barrister. Later in his career he became a Justice of the Peace (as his father had been) in Berkshire. In 1895 he was elected to the House of Commons for the Liberal Unionist Party, becoming a member of parliament for Truro from 1895 to 1906.

He was also a prominent Unitarian. He and his brother James between them donated £5000 – equal to half of the actual building costs – to the fund for the construction of Essex Street Chapel, the headquarters of British Unitarianism.[1]

He married Edith Jane Smith, daughter of John Benjamin Smith, in 1874. Their only son, Edwin, was born in 1878, but died two days later. On 2 February 1898 Edwin changed his name by Royal Licence to Durning-Lawrence, in honour of his wife's maternal grandfather,[2] and was created 1st Baronet Durning-Lawrence, of King's Ride, Ascot in the County of Berkshire and of Carlton House Terrace in the County of London on 10 March the same year.[3][4] In the absence of a male heir, on his death, his baronetcy became extinct.[4]

He is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery south of the main east-west path not far from the main east entrance.

Writings

editDurning-Lawrence was a prolific author. He wrote The Progress of a Century; or, The Age of Iron and Steam (1886), The Pope and the Bible (1888) and A Short History of Lighting from the Earliest Times (1895).

Lawrence became most famous as an advocate of Baconian theory, to which he was converted after reading Ignatius L. Donnelly's The Great Cryptogram. He wrote a number of books on the topic, the most notable of which was Bacon is Shake-Speare (1910). He also wrote The Shakespeare Myth (1912), "Macbeth" Proves Bacon is Shakespeare (1913), and Key to Milton's Epitaph on Shakespeare (1914).[5]

Following Donnelly, Durning-Lawrence believed that the key to proving Bacon's authorship was the discovery of cyphers within the plays which were hidden there by Bacon. His writings were also notable for the virulence with which he heaped abuse on William Shakespeare of Stratford:

England is now declining any longer to dishonour and defame the greatest Genius of all time by continuing to identify him with the mean, drunken, ignorant, and absolutely unlettered, rustic of Stratford who never in his life wrote so much as his own name and in all probability was totally unable to read one single line of print.[6]

Durning-Lawrence's vehemence and assertiveness in promoting his views was widely remarked upon. He sent copies of his book to public libraries in Britain and to schools, prompting expressions of concern from Shakespeare scholars who believed unwary readers would be misled.[5]

Durning-Lawrence's most famous argument in Bacon is Shake-Speare was his suggestion that the word Honorificabilitudinitatibus, used in the play Love's Labour's Lost, is an anagram for hi ludi, F. Baconis nati, tuiti orbi, Latin for "these plays, F. Bacon's offspring, are preserved for the world".[7] He derived the argument from an earlier book by Isaac Hull Platt.[8] Samuel Schoenbaum later argued that the anagram overlooks the fact that Bacon would have written the genitive of his name as Baconi (from Baconus), never Baconis (which assumes his name was Baco).[9] John Sladek also showed that the word could also be anagrammatised as I, B. Ionsonii, uurit [writ] a lift'd batch, thus "proving" that Shakespeare's works were written by Ben Jonson.[10] Durning-Lawrence also claimed that the Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare contained visual codes pointing to the secret authorship. He wrote, "there is no question – there can be no possible question – that in fact it is a cunningly drawn cryptographic picture, shewing two left arms and a mask... Especially note that the ear is a mask ear and stands out curiously; note also how distinct the line shewing the edge of the mask appears."[11]

Bacon, Durning-Lawrence believed, also wrote Don Quixote, in English; Cervantes was merely the Spanish translator of Bacon's version.[5]

University of London Archive

editDurning-Lawrence's archive was donated to the University of London library in 1929, and established there in 1931. It has been described as "a very important collection of about 7,000 volumes largely of seventeenth-century literature containing one of the best collections in the world on Sir Francis Bacon and valuable collections on Shakespeare and Defoe."[12] It is still part of the University of London library, Senate House Library.[13]

He also left an endowment to the university. In the 1920s the artist Henry Tonks, who felt the need for a stronger presence of History of Art within the university, was able to convert the endowment into a chair in that discipline at University College, despite the fact that Durning-Lawrence himself had no especial interest in the subject (though he had donated thirteen paintings to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1901). The first holder of the Durning-Lawrence chair was Tancred Borenius.[14]

Wilmot controversy

editIn 1932, the year after the library was opened, the Shakespeare scholar Allardyce Nicoll published an article on a manuscript it contained written by James Corton Cowell, entitled "Some reflections on the life of William Shakespeare". The manuscript was a lecture delivered to the Ipswich Philosophic Society in 1805. It stated that an 18th-century clergyman, James Wilmot, had identified Bacon as the hidden author of Shakespeare's works. Wilmot's study of local history in the Stratford area convinced him that Shakespeare could not have authored the works attributed to him. He came to this conclusion in 1781, more than 80 years before the Baconian argument was first published by Delia Bacon and W.H. Smith.[15] Wilmot destroyed all evidence of his theory, confiding his findings only to Cowell.[16][17][18]

The authenticity of Cowell's "Reflections" was accepted by Shakespearean scholars for many years, but was challenged in 2002–2003 by John Rollett, Daniel Wright and Alan H. Nelson. Rollett could find no historical traces of Cowell, the Ipswich Philosophic Society, or its supposed president, Arthur Cobbold.[19] In 2010, James S. Shapiro declared the document a forgery based on facts stated in the text about Shakespeare that were not discovered or publicised until decades after the purported date of composition.[20] It is not known whether the forgery was introduced to Durning-Lawrence's archive during his life or after his death; however he never refers to it in his own writings.

Notes

edit- ^ ch 3, Rowe, Mortimer, B.A., D.D. The History of Essex Hall. London: Lindsey Press, 1959.

- ^ "No. 26937". The London Gazette. 11 February 1898. p. 871.

- ^ "No. 26946". The London Gazette. 11 March 1898. p. 1504.

- ^ a b L. G. Pine, The New Extinct Peerage 1884–1971: Containing Extinct, Abeyant, Dormant and Suspended Peerages With Genealogies and Arms, London: Heraldry Today, 1972, p. 217 ISBN 0806305215

- ^ a b c K. E. Attar (2004). "Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence: A Baconian and his Books" (PDF). The Library. 5 (3): 294–315. doi:10.1093/library/5.3.294.

- ^ Durning-Lawrence, E., Bacon is Shakespeare, p. 82

- ^ Baconian theory. encyclopedia.com

- ^ K. K. Ruthven, Faking Literature, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p.102

- ^ Samuel Schoenbaum, Shakespeare's Lives, Oxford University Press, 2nd ed.1991 p.421

- ^ Deborah J. Leslie and Benjamin Griffin (5 March 2003) Transcription of early letter forms in rare materials cataloging Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Prepared for the DCRM Conference, 10–13 March 2003

- ^ Durning-Lawrence also claims that other engravings by Droeshout "may be similarly correctly characterised as cunningly composed, in order to reveal the true facts of the authorship of such works, unto those who were capable of grasping the hidden meaning of his engravings." Edwin Durning-Lawrence, Bacon Is Shake-Speare, John McBride Co., New York, 1910, pp. 23, 79–80.

- ^ Raymond Irwin and Ronald Staveley (eds), The Libraries of London, 2nd ed, London, 1964, p. 146.

- ^ "Durning-Lawrence Library". Senate House Library. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ University College, History of Art department Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. ucl.ac.uk

- ^ Nichol, A, "The First Baconian", Times Literary Supplement, 25 February 1932, p. 128. Reply by William Jaggard, 3 March, p. 155; response from Nicoll, 10 March, p. 17.

- ^ Alfred Harbage, Alfred. Conceptions of Shakespeare, Harvard University Press, 1966, p. 111

- ^ LoMonico, Michael. The Shakespeare Book of Lists: The Ultimate Guide to the Bard, Career Press, 2001, p. 28 ISBN 1564145247

- ^ Shapiro, James. "Forgery on Forgery," TLS (26 March 2010), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Niederkorn, William S. "Absolute Will", The Brooklyn Rail (April 2010); Baca, Nathan. "Wilmot Did Not; The 'First' Authorship Story Called Possible Baconian Hoax", Shakespeare Matters 2 Archived 11 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Summer 2003); Brenda James, W. D. Rubinstein, The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare, Pearson Education, 2005, p. 325.

- ^ Shapiro, James. Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, Faber, 2010, pp. 11–14 ISBN 1416541632.

References

editExternal links

edit- The Durning-Lawrence library at Senate House Library, University of London Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Edwin Durning-Lawrence

- Edwin Durning-Lawrence archives

- Works by Edwin Durning-Lawrence at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edwin Durning-Lawrence at the Internet Archive