The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (Cocos Islands Malay: Pulu Kokos [Keeling]), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (/ˈkoʊkəs/;[5][6] Cocos Islands Malay: Pulu Kokos [Keeling]), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and relatively close to the Indonesian island of Sumatra. The territory's dual name (official since the islands' incorporation into Australia in 1955) reflects that the islands have historically been known as either the Cocos Islands or the Keeling Islands.

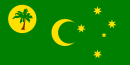

Cocos (Keeling) Islands | |

|---|---|

| Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Pulu Kokos (Keeling) (Cocos Islands Malay) Wilayah Kepulauan Cocos (Keeling) (Malay) | |

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "Advance Australia Fair" | |

Location of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (circled in red) | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Annexed by the United Kingdom | 1857 |

| Transferred from Singapore to Australia | 23 November 1955 |

| Capital | West Island 12°11′13″S 96°49′42″E / 12.18694°S 96.82833°E |

| Largest village | Bantam (Home Island) |

| Official languages | None |

| Spoken languages | |

| Government | Directly administered dependency |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Sam Mostyn | |

| Farzian Zainal[1] | |

| Aindil Minkom | |

| Parliament of Australia | |

• Senate | represented by Northern Territory senators |

| included in the Division of Lingiari | |

| Area | |

• Total | 14 km2 (5.4 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Highest elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 593[2] (not ranked) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | US$11,012,550[3] (not ranked) |

• Per capita | $18,570.91 (not ranked) |

| Currency | Australian dollar (AU$) (AUD) |

| Time zone | UTC+06:30 |

| Driving side | left[4] |

| Calling code | +61 891 |

| Postcode | WA 6799 |

| ISO 3166 code | CC |

| Internet TLD | .cc |

The territory consists of two atolls made up of 27 coral islands, of which only two – West Island and Home Island – are inhabited. The population of around 600 people consists mainly of Cocos Malays and Cocos Java, who mostly practise Sunni Islam and speak a dialect of Malay as their first language.[7] The territory is administered by the Australian federal government's Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts as an Australian external territory and together with Christmas Island (which is about 960 kilometres (600 mi) to the east) forms the Australian Indian Ocean Territories administrative grouping. However, the islanders do have a degree of self-government through the local shire council. Many public services – including health, education, and policing – are provided by the state of Western Australia, and Western Australian law applies except where the federal government has determined otherwise. The territory also uses Western Australian postcodes.

The islands were discovered in 1609 by the British sea captain William Keeling, but no settlement occurred until the early 19th century. One of the first settlers was John Clunies-Ross, a Scottish merchant; much of the island's current population is descended from the Malay workers he brought in to work his copra plantation. The Clunies-Ross family ruled the islands as a private fiefdom for almost 150 years, with the head of the family usually recognised as resident magistrate. The British annexed the islands in 1857, and for the next century they were administered from either Ceylon or Singapore. The territory was transferred to Australia in 1955, although until 1979 virtually all of the territory's real estate still belonged to the Clunies-Ross family.

Name

editThe islands have been called the Cocos Islands (from 1622), the Keeling Islands (from 1703), the Cocos–Keeling Islands (since James Horsburgh in 1805) and the Keeling–Cocos Islands (19th century).[8] Cocos refers to the abundant coconut trees, while Keeling refers to William Keeling, who discovered the islands in 1609.[8]

| Cocos Islands Act 1955 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to enable Her Majesty to place the Cocos or Keeling Islands under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia, and for purposes connected therewith. |

| Citation | 3 & 4 Eliz. 2. c. 5 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 29 March 1955 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1976 |

Status: Repealed | |

John Clunies-Ross,[9] who sailed there in the Borneo in 1825, called the group the Borneo Coral Isles, restricting Keeling to North Keeling, and calling South Keeling "the Cocos properly so called".[10][11] The form Cocos (Keeling) Islands, attested from 1916,[12] was made official by the Cocos Islands Act 1955 (3 & 4 Eliz. 2. c. 5).[8][failed verification]

The territory's Malay name is Pulu Kokos (Keeling). Sign boards on the island also feature Malay translations.[13][14]

Geography

editThe Cocos (Keeling) Islands consist of two flat, low-lying coral atolls with an area of 14.2 square kilometres (5.5 sq mi), 26 kilometres (16 mi) of coastline, a highest elevation of 5 metres (16 ft) and thickly covered with coconut palms and other vegetation. The climate is pleasant, moderated by the southeast trade winds for about nine months of the year and with moderate rainfall. Tropical cyclones may occur in the early months of the year.

North Keeling Island is an atoll consisting of just one C-shaped island, a nearly closed atoll ring with a small opening into the lagoon, about 50 metres (160 ft) wide, on the east side. The island measures 1.1 square kilometres (270 acres) in land area and is uninhabited. The lagoon is about 0.5 square kilometres (120 acres). North Keeling Island and the surrounding sea to 1.5 km (0.93 mi) from shore form the Pulu Keeling National Park, established on 12 December 1995. It is home to the only surviving population of the endemic, and endangered, Cocos Buff-banded Rail.

South Keeling Islands is an atoll consisting of 24 individual islets forming an incomplete atoll ring, with a total land area of 13.1 square kilometres (5.1 sq mi). Only Home Island and West Island are populated.[15] The Cocos Malays maintain weekend shacks, referred to as pondoks, on most of the larger islands.

| Islet (Malay name) |

Translation of Malay name | English name | Area (approx.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | mi2 | ||||

| 1 | Pulau Luar | Outer Island | Horsburgh Island | 1.04 | 0.40 |

| 2 | Pulau Tikus | Mouse Island | Direction Island | ||

| 3 | Pulau Pasir | Sand Island | Workhouse Island | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 4 | Pulau Beras | Rice Island | Prison Island | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 5 | Pulau Gangsa | Copper Island | Closed sandbar, now part of Home Island | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 6 | Pulau Selma | Home Island | 0.95 | 0.37 | |

| 7 | Pulau Ampang Kechil | Little Ampang Island | Scaevola Islet | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 8 | Pulau Ampang | Ampang Island | Canui Island | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 9 | Pulau Wa-idas | Ampang Minor | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| 10 | Pulau Blekok | Reef Heron Island | Goldwater Island | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 11 | Pulau Kembang | Flower Island | Thorn Island | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 12 | Pulau Cheplok | Cape Gooseberry Island | Gooseberry Island | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 13 | Pulau Pandan | Pandanus Island | Misery Island | 0.24 | 0.09 |

| 14 | Pulau Siput | Shell Island | Goat Island | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| 15 | Pulau Jambatan | Bridge Island | Middle Mission Isle | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 16 | Pulau Labu | Pumpkin Island | South Goat Island | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 17 | Pulau Atas | Up Wind Island | South Island | 3.63 | 1.40 |

| 18 | Pulau Kelapa Satu | One Coconut Island | North Goat Island | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 19 | Pulau Blan | East Cay | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| 20 | Pulau Blan Madar | Burial Island | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| 21 | Pulau Maria | Maria Island | West Cay | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 22 | Pulau Kambing | Goat Island | Keelingham Horn Island | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 23 | Pulau Panjang | Long Island | West Island | 6.23 | 2.41 |

| 24 | Pulau Wak Bangka | Turtle Island | 0.22 | 0.08 | |

There are no rivers or lakes on either atoll. Fresh water resources are limited to water lenses on the larger islands, underground accumulations of rainwater lying above the seawater. These lenses are accessed through shallow bores or wells.

Flora and fauna

editClimate

editCocos (Keeling) Islands experience a tropical rainforest climate (Af) according to the Köppen climate classification; the archipelago lies approximately midway between the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn. The archipelago has two distinct seasons, the wet season and the dry season. The wettest month is April with precipitation totaling 262.6 millimetres (10.34 in), and the driest month is October with precipitation totaling 88.2 millimetres (3.47 in). Due to the strong maritime control, temperatures vary little although its location is some distance from the Equator. The hottest month is March with an average high temperature of 30.0 °C (86.0 °F), while the coolest month is September with an average low temperature of 24.2 °C (75.6 °F).

| Climate data for Cocos Islands Airport (averages 1991–2020; extremes 1952–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.7 (90.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 25.2 (77.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 151.7 (5.97) |

207.1 (8.15) |

234.4 (9.23) |

248.9 (9.80) |

187.7 (7.39) |

187.3 (7.37) |

180.9 (7.12) |

102.0 (4.02) |

86.2 (3.39) |

84.8 (3.34) |

86.9 (3.42) |

121.4 (4.78) |

1,879.3 (73.98) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 13.7 | 15.3 | 19.2 | 18.7 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 21.3 | 17.0 | 15.3 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 192.1 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[16] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editAccording to the 2021 Australian Census, the population of the Cocos Islands is 593 people.[2] The gender distribution stands at an approximate 51% male and 49% female.[2] The median age of the population is 40 years, slightly older than the median Australian population age of 38 years.[17] As of 2021, there are no people living on the Cocos Islands who identify as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander).[2]

Religion in Cocos Islands (2021) [2]

The majority religion of the Cocos Islands is Islam, with 65.6% of the total population identifying as Muslim, followed by Unspecified (15.3%), Non-religious (14.0%), Catholic (2.0%), Anglican (1.5%). The remaining 1.6% of Cocos Islanders identify as secular or hold various other beliefs (including atheism, agnosticism and unspecified spiritual beliefs).[2]

73.5% of the population were born in Australia - either on the mainland, on the Cocos Islands, or in another Australian territory. The remaining 26.5% come from other countries, including Malaysia (4.0%), England (1.3%), New Zealand (1.2%), Singapore (0.5%) and Argentina (0.5%), among others.[2] 61.2% of the population speak Malay at home, while 19.1% speak English, and 3.5% speak another language (including Spanish and various Austronesian and African languages).[2]

Kaum Ibu (Women's Group) is a women's rights organisation that represents the view of women at a local and national level.[18]

History

editDiscovery and early history

editThe archipelago was discovered in 1609 by Captain William Keeling of the East India Company, on a return voyage from the East Indies. North Keeling was sketched by Ekeberg, a Swedish captain, in 1749, showing the presence of coconut palms. It also appears on a 1789 chart produced by British hydrographer Alexander Dalrymple.[20]

In 1825, Scottish merchant seaman Captain John Clunies-Ross stopped briefly at the islands on a trip to India, nailing up a Union Jack and planning to return and settle on the islands with his family in the future.[21] Wealthy Englishman Alexander Hare had similar plans, and hired a captain – coincidentally, Clunies-Ross's brother – to bring him and a volunteer harem of 40 Malay women to the islands, where he hoped to establish his private residence.[22] Hare had previously served as resident of Banjarmasin, a town in Borneo, and found that "he could not confine himself to the tame life that civilisation affords".[22]

Clunies-Ross returned two years later with his wife, children and mother-in-law, and found Hare already established on the island and living with the private harem. A feud grew between the two.[22] Clunies-Ross's eight sailors "began at once the invasion of the new kingdom to take possession of it, women and all".[22]

After some time, Hare's women began deserting him, and instead finding themselves partners amongst Clunies-Ross's sailors.[23] Disheartened, Hare left the island. He died in Bencoolen in 1834.[24] Encouraged by members of the former harem, Clunies-Ross then recruited Malays to come to the island for work and wives.

Clunies-Ross's workers were paid in a currency called the Cocos rupee, a currency John Clunies-Ross minted himself that could only be redeemed at the company store.[25]

On 1 April 1836, HMS Beagle under Captain Robert FitzRoy arrived to take soundings to establish the profile of the atoll as part of the survey expedition of the Beagle. To the naturalist Charles Darwin, aboard the ship, the results supported a theory he had developed of how atolls formed, which he later published as The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. He studied the natural history of the islands and collected specimens.[26] Darwin's assistant Syms Covington noted that "an Englishman [he was in fact Scottish] and HIS family, with about sixty or seventy mulattos from the Cape of Good Hope, live on one of the islands. Captain Ross, the governor, is now absent at the Cape."

Annexation by the British Empire

editThe islands were annexed by the British Empire in 1857.[27] This annexation was carried out by Captain Stephen Grenville Fremantle in command of HMS Juno. Fremantle claimed the islands for the British Empire and appointed Ross II as Superintendent.[28] In 1878, by Letters Patent, the Governor of Ceylon was made Governor of the islands, and, by further Letters Patent in 1886,[29] responsibility for the islands was transferred to the Governor of the Straits Settlement to exercise his functions as "Governor of Cocos Islands".[27]

The islands were made part of the Straits Settlement under an Order in Council of 20 May 1903.[30] Meanwhile, in 1886 Queen Victoria had, by indenture, granted the islands in perpetuity to John Clunies-Ross.[31] The head of the family enjoyed semi-official status as Resident Magistrate and Government representative.[31]

In 1901 a telegraph cable station was established on Direction Island. Undersea cables went to Rodrigues, Mauritius, Batavia, Java and Fremantle, Western Australia. In 1910 a wireless station was established to communicate with passing ships. The cable station ceased operation in 1966.[32]

World War I

editOn the morning of 9 November 1914, the islands became the site of the Battle of Cocos, one of the first naval battles of World War I. A landing party from the German cruiser SMS Emden captured and disabled the wireless and cable communications station on Direction Island, but not before the station was able to transmit a distress call. An Allied troop convoy was passing nearby, and the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney was detached from the convoy escort to investigate.

Sydney spotted the island and Emden at 09:15, with both ships preparing for combat. At 11:20, the heavily damaged Emden beached herself on North Keeling Island. The Australian warship broke to pursue Emden's supporting collier, which scuttled herself, then returned to North Keeling Island at 16:00. At this point, Emden's battle ensign was still flying: usually a sign that a ship intends to continue fighting. After no response to instructions to lower the ensign, two salvoes were shot into the beached cruiser, after which the Germans lowered the flag and raised a white sheet. Sydney had orders to ascertain the status of the transmission station, but returned the next day to provide medical assistance to the Germans.

Casualties totaled 134 personnel aboard Emden killed, and 69 wounded, compared to four killed and 16 wounded aboard Sydney. The German survivors were taken aboard the Australian cruiser, which caught up to the troop convoy in Colombo on 15 November, then transported to Malta and handed over the prisoners to the British Army. An additional 50 German personnel from the shore party, unable to be recovered before Sydney arrived, commandeered a schooner and escaped from Direction Island, eventually arriving in Constantinople. Emden was the last active Central Powers warship in the Indian or Pacific Ocean, which meant troopships from Australia and New Zealand could sail without naval escort, and Allied ships could be deployed elsewhere.

World War II

editDuring World War II, the cable station was once again a vital link. The Cocos were valuable for direction finding by the Y service, the worldwide intelligence system used during the war.[33]

Allied planners noted that the islands might be seized as an airfield for German planes and as a base for commerce raiders operating in the Indian Ocean. Following Japan's entry into the war, Japanese forces occupied neighbouring islands. To avoid drawing their attention to the Cocos cable station and its islands' garrison, the seaplane anchorage between Direction and Horsburgh islands was not used. Radio transmitters were also kept silent, except in emergencies.[34]

After the Fall of Singapore in 1942, the islands were administered from Ceylon and West and Direction Islands were placed under Allied military administration. The islands' garrison initially consisted of a platoon from the British Army's King's African Rifles, located on Horsburgh Island, with two 6-inch (152.4 mm) guns to cover the anchorage. The local inhabitants all lived on Home Island. Despite the importance of the islands as a communication centre, the Japanese made no attempt either to raid or to occupy them and contented themselves with sending over a reconnaissance aircraft about once a month.

On the night of 8–9 May 1942, 15 members of the garrison, from the Ceylon Defence Force, mutinied under the leadership of Gratien Fernando. The mutineers were said to have been provoked by the attitude of their British officers and were also supposedly inspired by Japanese anti-British propaganda. They attempted to take control of the gun battery on the islands. The Cocos Islands Mutiny was crushed, but the mutineers murdered one non-mutinous soldier and wounded one officer. Seven of the mutineers were sentenced to death at a trial that was later alleged to have been improperly conducted, though the guilt of the accused was admitted. Four of the sentences were commuted, but three men were executed, including Fernando. These were to be the only British Commonwealth soldiers executed for mutiny during the Second World War.[35]

On 25 December 1942, the Japanese submarine I-166 bombarded the islands but caused no damage.[36]

Later in the war, two airstrips were built, and three bomber squadrons were moved to the islands to conduct raids against Japanese targets in South East Asia and to provide support during the planned reinvasion of Malaya and reconquest of Singapore. The first aircraft to arrive were Supermarine Spitfire Mk VIIIs of No. 136 Squadron RAF.[37] They included some Liberator bombers from No. 321 (Netherlands) Squadron RAF (members of exiled Dutch forces serving with the Royal Air Force), which were also stationed on the islands. When in July 1945 No. 99 and No. 356 RAF squadrons arrived on West Island, they brought with them a daily newspaper called Atoll which contained news of what was happening in the outside world. Run by airmen in their off-duty hours, it achieved fame when dropped by Liberator bombers on POW camps over the heads of the Japanese guards.

In 1946, the administration of the islands reverted to Singapore and it became part of the Colony of Singapore.[38]

Transfer to Australia

editOn 23 November 1955, the islands were transferred from the United Kingdom to the Commonwealth of Australia. Immediately before the transfer the islands were part of the United Kingdom's Colony of Singapore, in accordance with the Straits Settlements (Repeal) Act, 1946 of the United Kingdom[39] and the British Settlements Acts, 1887 and 1945, as applied by the Act of 1946.[27] The legal steps for effecting the transfer were as follows:[40]

- The Commonwealth Parliament and the Government requested and consented to the enactment of a United Kingdom Act for the purpose.

- The Cocos Islands Act, 1955, authorised Her Majesty, by Order in Council, to direct that the islands should cease to form part of the Colony of Singapore and be placed under the authority of the Commonwealth.

- By the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act, 1955, the Parliament of the Commonwealth provided for the acceptance of the islands as a territory under the authority of the Commonwealth and for its government.

- The Cocos Islands Order in Council, 1955, made under the United Kingdom Act of 1955, provided that upon the appointed day (23 November 1955) the islands should cease to form part of the Colony of Singapore and be placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia.

The reason for this comparatively complex machinery was due to the terms of the Straits Settlement (Repeal) Act, 1946. According to Sir Kenneth Roberts-Wray "any other procedure would have been of doubtful validity".[41] The separation involved three steps: separation from the Colony of Singapore; transfer by United Kingdom and acceptance by Australia.

H. J. Hull was appointed the first official representative (now administrator) of the new territory. He had been a lieutenant-commander in the Royal Australian Navy and was released for the purpose. Under Commonwealth Cabinet Decision 1573 of 9 September 1958, Hull's appointment was terminated and John William Stokes was appointed on secondment from the Northern Territory police. A media release at the end of October 1958 by the Minister for Territories, Hasluck, commended Hull's three years of service on Cocos.

Stokes served in the position from 31 October 1958 to 30 September 1960. His son's boyhood memories and photos of the Islands have been published.[42] C. I. Buffett MBE from Norfolk Island succeeded him and served from 28 July 1960 to 30 June 1966, and later acted as Administrator back on Cocos and on Norfolk Island. In 1974, Ken Mullen wrote a small book[43] about his time with wife and son from 1964 to 1966 working at the Cable Station on Direction Island.

In the 1970s, the Australian government's dissatisfaction with the Clunies-Ross feudal style of rule of the island increased. In 1978, Australia forced the family to sell the islands for the sum of A$6,250,000, using the threat of compulsory acquisition. By agreement, the family retained ownership of Oceania House, their home on the island. In 1983, the Australian government reneged on this agreement and told John Clunies-Ross that he should leave the Cocos. The following year the High Court of Australia ruled that resumption of Oceania House was unlawful, but the Australian government ordered that no government business was to be granted to Clunies-Ross's shipping company, an action that contributed to his bankruptcy.[44] John Clunies-Ross later moved to Perth, Western Australia. However, some members of the Clunies-Ross family still live on the Cocos.

Extensive preparations were undertaken by the government of Australia to prepare the Cocos Malays to vote in their referendum of self-determination. Discussions began in 1982, with an aim of holding the referendum, under United Nations supervision, in mid-1983. Under guidelines developed by the UN Decolonization Committee, residents were to be offered three choices: full independence, free association, or integration with Australia. The last option was preferred by both the islanders and the Australian government. A change in government in Canberra following the March 1983 Australian elections delayed the vote by one year. While the Home Island Council stated a preference for a traditional communal consensus "vote", the UN insisted on a secret ballot. The referendum was held on 6 April 1984, with all 261 eligible islanders participating, including the Clunies-Ross family: 229 voted for integration, 21 for Free Association, nine for independence, and two failed to indicate a preference.[45] In the first decade of the 21st century, a series of disputes have occurred between the Muslim and the non-Muslim population of the islands.[46]

The airstrip on West Island has an airstrip that is more than two kilometres long and is designed to accommodate Boeing 737 passenger flights and smaller military planes. In 2023, the Australian parliament approved plans to extend the airstrip by 150 metres so that it could take Boeing P-8 Poseidon aircraft capable of low-level anti-submarine warfare operations and high-tech military surveillance. Construction was scheduled to start in 2024 and be completed by 2026.[15] Prior to the upgrade, the United States had been using the airstrip for several decades as a stopover point between Diego Garcia and Guam, and as a partial alternative to the Paya Lebar Air Base.[47]

Indigenous status

editDescendants of the Cocos Malays brought to the islands from the Malay Peninsula, the Indonesian archipelago, Southern Africa and New Guinea by Hare and by Clunies-Ross as indentured workers, slaves or convicts are as of 2019[update] seeking recognition from the Australian government to be acknowledged as Indigenous Australians.[48]

Government

editThe capital of the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands is West Island while the largest settlement is the village of Bantam, on Home Island.[49]

Governance of the islands is based on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955[50][51] and depends heavily on the laws of Australia. The islands are administered from Canberra by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts through a non-resident Administrator appointed by the Governor-General. They were previously the responsibility of the Department of Transport and Regional Services (before 2007), the Attorney-General's Department (2007–2013), Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (2013–2017) and Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities (2017–2020).[52][53]

As of November 2023, the Administrator is Farzian Zainal, she is also the Administrator of Christmas Island.[54] These two territories comprise the Australian Indian Ocean Territories. The Australian Government provides Commonwealth-level government services through the Christmas Island Administration and the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts.[55] As per the Federal Government's Territories Law Reform Act 1992, which came into force on 1 July 1992, Western Australian laws are applied to the Cocos Islands, "so far as they are capable of applying in the Territory";[56] non-application or partial application of such laws is at the discretion of the federal government. The Act also gives Western Australian courts judicial power over the islands. The Cocos Islands remain constitutionally distinct from Western Australia, however; the power of the state to legislate for the territory is power-delegated by the federal government. The kind of services typically provided by a state government elsewhere in Australia are provided by departments of the Western Australian Government, and by contractors, with the costs met by the federal government.[57]

There also exists a unicameral Cocos (Keeling) Islands Shire Council with seven seats. A full term lasts four years, though elections are held every two years; approximately half the members retire each two years.[58] As of March 2024[update] the president of the shire is Aindil Minkom.[59] The most recent local election took place on 21 October 2023 alongside elections on Christmas Island.[60]

Federal politics

editCocos (Keeling) Islands residents who are Australian citizens also vote in federal elections. Cocos (Keeling) Islanders are represented in the House of Representatives by the member for the Division of Lingiari (in the Northern Territory) and in the Senate by Northern Territory senators.[63] At the 2022 Australian federal election the Labor Party received absolute majorities from Cocos electors in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.[62][61]

Defence and law enforcement

edit

Defence is the responsibility of the Australian Defence Force. Until 2023, there were no active military installations or defence personnel on the island; the administrator could request the assistance of the Australian Defence Force if required.

In 2016, the Australian Department of Defence announced that the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Airport (West Island) would be upgraded to support the Royal Australian Air Force's P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft.[64] Work was scheduled to begin in early 2023 and be completed by 2026. The airfield will act as a forward operating base for Australian surveillance and electronic warfare aircraft in the region.[65][66]

The Royal Australian Navy and Australian Border Force also deploy Cape and Armidale-class patrol boats to conduct surveillance and counter-migrant smuggling patrols in adjacent waters.[67] As of 2023, the Navy's Armidale-class boats are in the process of being replaced by larger Arafura-class offshore patrol vessels.[68][69]

Civilian law enforcement and community policing is provided by the Australian Federal Police. The normal deployment to the island is one sergeant and one constable. These are augmented by two locally engaged Special Members who have police powers.

Courts

editSince 1992, court services have been provided by the Western Australian Department of the Attorney-General under a service delivery arrangement with the Australian Government. Western Australian Court Services provide Magistrates Court, District Court, Supreme Court, Family Court, Children's Court, Coroner's Court and Registry for births, deaths and marriages and change of name services. Magistrates and judges from Western Australia convene a circuit court as required.

Health care

editHome Island and West Island have medical clinics providing basic health services, but serious medical conditions and injuries cannot be treated on the island and patients are sent to Perth for treatment, a distance of 3,000 km (1,900 mi).

Economy

editThe population of the islands is approximately 600. There is a small and growing tourist industry focused on water-based or nature activities. In 2016, a beach on Direction Island was named the best beach in Australia by Brad Farmer, an Aquatic and Coastal Ambassador for Tourism Australia and co-author of 101 Best Beaches 2017.[70][71]

Small local gardens and fishing contribute to the food supply, but most food and most other necessities must be imported from Australia or elsewhere.

The Cocos Islands Cooperative Society Ltd. employs construction workers, stevedores, and lighterage worker operations. Tourism employs others. The unemployment rate was 6.7% in 2011.[72]

Plastic pollution

editA 2019 study led by Jennifer Lavers from the University of Tasmania's Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies published in the journal Scientific Reports estimated the volume of plastic rubbish on the Islands as around 414 million pieces, weighing 238 tonnes, 93% of which lies buried under the sand. It said that previous surveys which only assessed surface garbage probably "drastically underestimated the scale of debris accumulation". The plastic waste found in the study consisted mostly of single-use items such as bottles, plastic cutlery, bags and drinking straws.[73][74][75][76]

Strategic importance

editThis section needs to be updated. (November 2017) |

The Cocos Islands are strategically important because of their proximity to shipping lanes in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The islands could be used to monitor the Malacca, Sunda and Lombok straits.[15][77] The United States and Australia have expressed interest in stationing surveillance drones on the Cocos Islands.[78] Euronews described the plan as Australian support for an increased American presence in Southeast Asia, but expressed concern that it was likely to upset Chinese officials.[79]

James Cogan has written for the World Socialist Web Site that the plan to station surveillance drones at Cocos is one component of former US President Barack Obama's "pivot" towards Asia, facilitating control of the sea lanes and potentially allowing US forces to enforce a blockade against China.[77] After plans to construct airbases were reported on by The Washington Post,[80] Australian defence minister Stephen Smith stated that the Australian government views the "Cocos as being potentially a long-term strategic location, but that is down the track."[81] In 2023, Indian aircraft from their Navy and Air Force paid a visit to the islands. Australia hopes to further advance relationships with India in order to grow their monitoring strength in the Indian Ocean. [82]

Communications and transport

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

Transport

editThe Cocos (Keeling) Islands have fifteen kilometres (9.3 miles) of highway.

There is one paved airport on the West Island. A tourist bus operates on Home Island.

The only airport is Cocos (Keeling) Islands Airport with a single 2,441 m (8,009 ft) paved runway. Virgin Australia operates scheduled jet services from Perth Airport twice a week. The service also includes Christmas Island on the schedule. After 1952, the airport at Cocos Islands was a stop for airline flights between Australia and South Africa, and Qantas and South African Airways stopped there to refuel. The arrival of long-range jet aircraft ended this need in 1967.

The Cocos Islands Cooperative Society operates an interisland ferry, the Cahaya Baru, connecting West, Home and Direction Islands, as well as a bus service on West Island.[83]

There is a lagoon anchorage between Horsburgh and Direction islands for larger vessels, while yachts have a dedicated anchorage area in the southern lee of Direction Island. There are no major seaports on the islands.

Communications

editThe islands are connected within Australia's telecommunication system (with number range +61 8 9162 xxxx). Public phones are located on both West Island and Home Island. A reasonably reliable GSM mobile phone network (number range +61 406 xxx), run by CiiA (Christmas Island Internet Association), operates on Cocos (Keeling) Islands. SIM cards (full size) and recharge cards can be purchased from the Telecentre on West Island to access this service.

Australia Post provides mail services with the postcode 6799. There are post offices on West Island and Home Island. Standard letters and express post items are sent by air twice weekly, but all other mail is sent by sea and can take up to two months for delivery.

Internet

edit.cc is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Cocos (Keeling) Islands. It is administered by VeriSign through a subsidiary company eNIC, which promotes it for international registration as "the next .com"; .cc was originally assigned in October 1997 to eNIC Corporation of Seattle WA by the IANA. The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus also uses the .cc domain, along with .nc.tr.

Internet access on Cocos is provided by CiiA (Christmas Island Internet Association), and is supplied via satellite ground station on West Island, and distributed via a wireless PPPoE-based WAN on both inhabited islands. Casual internet access is available at the Telecentre on West Island and the Indian Ocean Group Training office on Home Island.

The National Broadband Network announced in early 2012 that it would extend service to Cocos in 2015 via high-speed satellite link.[84]

The Oman Australia Cable, completed in 2022, links Australia and Oman with a spur to the Cocos Islands.[85][86][87][88]

Media

editThe Cocos (Keeling) Islands have access to a range of modern communication services. Digital television stations are broadcast from Western Australia via satellite. A local radio station, 6CKI – Voice of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, is staffed by community volunteers and provides some local content.

Newspapers

editThe Cocos Islands Community Resource Centre publishes a fortnightly newsletter called The Atoll. It is available in paper and electronic formats.[89]

Radio

editTelevision

edit- Australian

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands receives a range of digital channels from Western Australia via satellite and is broadcast from the Airport Building on the West Island on the following VHF frequencies: ABC6, SBS7, WAW8, WOW10 and WDW11[90]

- Malaysian

From 2013 onwards, Cocos Island received four Malaysian channels via satellite: TV3, ntv7, 8TV and TV9.[citation needed][91]

Education

editThere is a school in the archipelago, Cocos Islands District High School, with campuses located on West Island (Kindergarten to Year 10), and the other on Home Island (Kindergarten to Year 6). CIDHS is part of the Western Australia Department of Education. School instruction is in English on both campuses, with Cocos Malay teacher aides assisting the younger children in Kindergarten, Pre-Preparatory and early Primary with the English curriculum on the Home Island Campus. The Home Language of Cocos Malay is valued whilst students engage in learning English.

Culture

editAlthough it is an Australian territory, the culture of the islands has extensive influences from Malaysia and Indonesia due to its predominantly ethnic Malay population.

Heritage listings

editThe West Island Mosque on Alexander Street is listed on the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List.[92]

Museum

editThe Pulu Cocos Museum on Home Island was established in 1987, in recognition of the fact that the distinct culture of Home Island needed formal preservation.[93][94] The site includes the displays on local culture and traditions, as well as the early history of the islands and their ownership by the Clunies-Ross family.[95][96] The museum also includes displays on military and naval history, as well as local botanical and zoological items.[97]

Marine park

editReefs near the islands have healthy coral and are home to several rare species of marine life. The region, along with the Christmas Island reefs, have been described as "Australia's Galapagos Islands".[98]

In the 2021 budget the Australian Government committed $A39.1M to create two new marine parks off Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. The parks will cover up to 740,000 square kilometres (290,000 sq mi) of Australian waters.[99] After months of consultation with local people, both parks were approved in March 2022, with a total coverage of 744,000 square kilometres (287,000 sq mi). The park will help to protect spawning of bluefin tuna from illegal international fishers, but local people will be allowed to practise fishing sustainably inshore in order to source food.[98]

Sport

editRugby league is a popular sport on the islands.[100] The Cocos Islands Golf Club, located on West Island and established in 1962, is the only golf course in the world that plays across an international airport runway.[101]

Unlike Norfolk Island, another external territory of Australia, the Cocos Islands do not participate in the Commonwealth Games or the Pacific Games.

Image gallery

edit- Gallery

-

Aerial view of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Airport (ICAO code: YPCC).

-

Compass stand from the bridge of HMAS Sydney, which destroyed the SMS Emden, installed at Port Macquarie, New South Wales, in 1929.

-

A broadside view of the wrecked Emden after her encounter with HMAS Sydney. Crew huddle on the wreck, awaiting rescue by Sydney.

-

The last bombing raid of World War II by 99, 356 and 321 Squadrons is cancelled, 15 August 1945.[102]

-

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip arrive at the Cocos Islands, April 1954.

-

Prince Philip waves goodbye as he and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by John Clunies-Ross, return to their ship from Home Island (1954).

-

Queen Elizabeth at a garden party held in her honour at Home Island (1954).

See also

edit- Banknotes of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Index of Cocos (Keeling) Islands-related articles

- Pearl Islands (Isla de Cocos, Panama; Cocos Island, Costa Rica).

Notes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ "RDA Appointments".

- ^ a b c d e f g h "2021 Census QuickStats: Cocos (Keeling) Islands". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au.

- ^ Lundy, Kate (2010). "Chapter 3: The economic environment of the Indian Ocean Territories". Inquiry into the changing economic environment in the Indian Ocean Territories (PDF). Parliament House, Canberra ACT: Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-642-79276-1.

- ^ "List of left- & right-driving countries".

- ^ "COCOS ISLANDS | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Cocos Keeling Islands (11 February 2021). "Cocos Keeling Islands - Destination WA 2020 - Motorised Canoe Safari". YouTube. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Woodroffe, C.D.; Berry, P.F. (February 1994). Scientific Studies in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands: An Introduction. Atoll Research Bulletin. Vol. 399. Washington DC: National Museum of Natural History. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Dynasties: Clunies-Ross". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Horsburgh, James (1841). "Islands to the Southward and South-eastward of Java; The Keeling or Cocos Islands". The India directory, or, Directions for sailing to and from the East Indies, China, Australia, and the interjacent ports of Africa and South America: comp. chiefly from original journals of the honourable company's ships, and from observations and remarks, resulting from the experience of twenty-one years in the navigation of those seas. Vol. 1 (5th ed.). London: W.H. Allen and Co. pp. 141–2.

- ^ Ross, J. C. (May 1835). "The Cocos' Isles". The Metropolitan. Peck and Newton. p. 220.

- ^ Weber, Max Carl Wilhelm; de Beaufort, Lieven Ferdinand (1916). The Fishes of the Indo-australian Archipelago. Brill Archive. p. 286. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Photo of a sign".

- ^ "10429811_10152701070713780_7000322669539587620_n1.jpg (960×716)". Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Mangan, Sinead (1 September 2023). "Some 'inconvenient Australians' fear their slice of paradise will be ruined in the name of national security". ABC News. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations. Cocos Island Airport". Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

- ^ "2021 Census QuickStats: Australia". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au.

- ^ Jupp, James; Jupp, Director Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80789-0.

- ^ Nationaal Archief, The Hague, archive 4.VEL inventorynumber 338

- ^ Pulu Keeling National Park Management Plan. Australian Government. 2004. ISBN 0-642-54964-8.

- ^ "Gleanings in Science, Volume 2". Baptist Mission Press. 1830. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Joshua Slocum, "Sailing Alone Around the World", p. 212 Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Clunies-Ross Chronicle Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morning Post (London) 20 March 1835

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Programmes - From Our Own Correspondent - The man who lost a 'coral kingdom'". Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ Keynes, Richard (2001), Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary, Cambridge University Press, pp. 413–418, archived from the original on 26 December 2016, retrieved 20 January 2009

- ^ a b c Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. p. 882

- ^ "The Cocos Islands". The Chambers's Journal. 76: 187–190. 1899. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. XXI, 512.

- ^ S.R.O. 1903 No. 478, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. XXI, 515

- ^ a b Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. p. 883

- ^ "Timeline of major dates". Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ McKay, S. 2012. The Secret Listeners. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978 1 78131 079 3

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands - Page 3 of 6 - Smoke Tree Manor". 19 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Cruise, Noel (2002). The Cocos Islands Mutiny. Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press. p. 248. ISBN 1-86368-310-0.

- ^ "Imperial Submarines". Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Fail, J.E.H. "FORWARD STRATEGIC AIR BASE COCOS ISLAND". rquirk.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Colony of Singapore. Government Gazette. (1 April 1946). The Singapore Colony Order in Council, 1946 (G.N. 2, pp. 2–3). Singapore: [s.n.]. Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SGG; White paper on Malaya (26 January 1946). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Tan, K. Y. L. (Ed.). (1999). The Singapore legal system (pp. 232–233). Singapore: Singapore University Press. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 SIN.

- ^ 9 & 10 G. 6, c. 37

- ^ Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. pp. 133–134

- ^ Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. p. 134

- ^ Stokes, Tony (2012). Whatever Will Be, I'll See: Growing Up in the 1940s, 50s and 60s in the Northern Territory, Christmas and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Tony Stokes. p. 238. ISBN 9780646575643.

- ^ Ken Mullen (1974). Cocos Keeling, the Islands Time Forgot. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. p. 122. ISBN 9780207131950. OCLC 1734040.

- ^ "Cabinet papers: The last King of Cocos loses his palace". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Kenneth Chen, "Pacific Island Development Plan: Cocos (Keeling) Islands- The Political Evolution of a Small Island Territory in the Indian Ocean" (1987): Mr Chen was Administrator, Cocos Islands, from December 1983 – November 1985.

- ^ "Lost in transition". www.theaustralian.com.au. 31 August 2009. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ Bashfield, Samuel (16 April 2019). "Australia's Cocos Islands Cannot Replace America's Troubled Diego Garcia". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ Herriman, Nicholas; Irving, David R.M.; Acciaioli, Greg; Winarnita, Monika; Kinajil, Trixie Tangit (25 June 2018). "A group of Southeast Asian descendants wants to be recognised as Indigenous Australians". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands Cities Database | Simplemaps.com". simplemaps.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ WebLaw – full resource metadata display Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ "Territories of Australia". Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

As part of the Machinery of Government Changes following the Federal Election on 29 November 2007, administrative responsibility for Territories has been transferred to the Attorney General's Department.

- ^ First Assistant Secretary, Territories Division (30 January 2008). "Territories of Australia". Attorney-General's Department. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

The Federal Government, through the Attorney-General's Department administers Ashmore and Cartier Islands, Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, the Coral Sea Islands, Jervis Bay, and Norfolk Island as Territories.

- ^ Farid, Farid (6 November 2023). "Malay Muslim engineer leads Christmas, Cocos Isles". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Administrative Arrangements Order made on 18 September 2013" (PDF). Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 18 September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Territories Law Reform Act 1992". 30 June 1992. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands governance and administration". Australian Government. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "Meet the Council". shire.cc. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Meet the Council". Shire of Cocos Islands. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Council Elections". Shire of Cocos Islands. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ a b

House of Representatives polling places:

- Home Island Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Home Island PPVC Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- West Island Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b

Senate polling places:

- Home Island Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Home Island PPVC Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- West Island Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Profile of the electoral division of Lingiari (NT)". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "2016 Defence White Paper (para. 4.66)" (PDF). defence.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "$384m cost blowout on ADF plan to upgrade airstrip, boost military presence on Cocos (Keeling) Islands". ABC. 15 January 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Layton, Peter (29 June 2023). "Australian Defence's Forgotten Indian Ocean Territories". Griffith Asia Insights. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ "Operation Resolute". Australian Government - Defence. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Third asylum seeker boat intercepted". Sky News. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Arafura Class OPV". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ Jackson, Belinda (4 December 2016). "Cossies Beach, Cocos (Keeling) Islands: Beach expert Brad Farmer names Australia's best beach 2017". traveller.com.au. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Bonnor, James (22 August 2016). "Australia appoints Brad Farmer to beach ambassador role". www.surfersvillage.com. XTreme Video. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands : Region Data Summary". Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ Smee, Ben (16 May 2019). "414 million pieces of plastic found on remote island group in Indian Ocean". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ J. L. Lavers; L. Dicks; M. R. Dicks; A. Finger (16 May 2019). "Significant plastic accumulation on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Australia". Scientific Reports. 9 (Article number 7102): 7102. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7102L. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43375-4. PMC 6522509. PMID 31097730.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (16 May 2019). "Plastic pollution: Flip-flop tide engulfs 'paradise' island". BBC News. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Kahn, Jo (17 May 2019). "Tonnes of plastic waste pollute Cocos Island beaches, and what you see is only a fragment". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ a b Cogan, James, "US Marines begin operations in northern Australia Archived 16 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine." World Socialist Web Site, 14 April 2012.

- ^ Whitlock, Craig, "U.S., Australia to broaden military ties amid Pentagon pivot to SE Asia Archived 9 February 2013 at archive.today", The Washington Post, 26 March 2012.

- ^ Grubel, James, "Australia open to US spy flights from Indian Ocean." Euronews, 28 March 2012. Archived 27 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (26 March 2012). "U.S., Australia announce deeper military ties amid Pentagon pivot to SE Asia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Hawley, Samantha (28 March 2012). "Cocos Islands: US military base, not in our lifetime". abc.net.au. ABC. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Brewster, David (6 July 2023). "Indian aircraft visit Cocos Islands as Australia strengthens its maritime security network". The Strategist. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Logistics Group - Cocos Islands Cooperative Society Ltd". Cocoscoop.cc. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Kidman, Alex, "NBN To Launch Satellites in 2015 Archived 12 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine." Gizmodo, 8 February 2012.

- ^ "$300M Oman-Australia cable switched on". www.arnnet.com.au. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Oman Australia Cable (OAC) Completes Final Landing in Oman". www.submarinenetworks.com. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "SUB.CO - Submarine Cable Infrastructure Development Specialists". www.sub.co. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Brock, Joe (6 July 2023). "Inside the subsea cable firm secretly helping America take on China". Reuters. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "The Atoll Newsletter". Shire of Cocos Keeling Islands. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "List of licensed broadcasting transmitters". ACMA. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ "There's An Island in Australia Full Of Malays That Nobody Knew About". hitz.syok.my. Retrieved 21 October 2024 – via hitzdotfm.

- ^ "West Island Mosque (Place ID 105219)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Conference, Museums Australia National (1997). Unlocking Museums: The Proceedings : 4th National Conference of Museums Australia Inc. Museums Australia. ISBN 978-0-949069-23-8.

- ^ "Cocos (Keeling) Islands Shadow Puppets". Australia Post Collectables. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Home Island | Cocos Keeling Islands". www.cocoskeelingislands.com.au. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ RACWA. "Things To Do on Christmas Island and Cocos Keeling Islands | RAC WA". RAC WA - For a better WA. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Cocos Museum". Commonwealth Walkway Trust. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ a b Birch, Laura (20 March 2022). "Indian Ocean marine parks off Christmas Island and Cocos Islands get the go-ahead". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Budget 2021–22" (PDF). Government of Australia. 11 May 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Indian Ocean adventures with rugby league". Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries. 11 October 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Wynne, Emma (22 June 2019). "Cocos Islands international airport runway doubles as part of local golf course". ABC News. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Maj-General J. T. Durrant (SA Air Force, Commanding Officer, Cocos Islands), watched by Wing Commander "Sandy" Webster (Commanding Officer, 99 Squadron), Squadron Leader Les Evans (Acting Commanding Officer, 356 Squadron) and Lieutenant Commander W. van Prooijen (Commanding Officer, 321 Squadron).

Sources

edit- This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. (Archived 2003 edition.)

- Clunies-Ross, John Cecil; Souter, Gavin. The Clunies-Ross Cocos Chronicle, Self, Perth 2009, ISBN 9780980586718.

- McGrath, Tony (2019). In Tropical Skies: A History of Aviation to Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Carlisle, WA: Hesperian Press. ISBN 9780859057561.

External links

edit- Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands homepage

- Areas of individual islets

- Atoll Research Bulletin vol. 403

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands Tourism website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 712.

- Noel Crusz, The Cocos Islands mutiny Archived 11 September 2001 at the Wayback Machine, reviewed by Peter Stanley (Principal Historian, Australian War Memorial).

- The man who lost a "coral kingdom"

- Amateur Radio DX Pedition to Cocos (Keeling) Islands VK9EC