The economy history of Iceland covers the development of its economy from the Settlement of Iceland in the late 9th century until the present.

The field of economic history in Iceland

editAccording to a 2011 review study by economic historian Guðmundur Jónsson,

Economic history as an independent field of study is of fairly recent origin in Iceland, emerging only in the last quarter of the twentieth century with the increased specialisation and differentiation of the history profession. With no separate economic history departments and in fact, only one general university, the University of Iceland in Reykjavík, it is not surprising that economic history has largely been in the hands of either historians educated within the broad church of history, non-professionals or scholars outside the history profession. Only in the last twenty years or so have specialist economic historians, educated abroad, entered the field and turned the subject into a distinct discipline.[1]

Pre-18th century economic history

editTrade in medieval Iceland was conducted through barter.[2]

According to the traditional nationalist historical narrative, which has been associated with historian Jón Jónsson Aðils (1869–1920), Iceland experienced a golden age from 874 (settlement) to the 11th century (this period has often been referred to as the Saga Age). This period of prosperity purportedly ended when Iceland fell under foreign rule (Jónsson 1903, 79, 88–89, 103, 105, 178).[3] Under foreign rule, the Icelandic nation declined and ultimately suffered humiliation (Jónsson 1903, 241-242).[3][4] Aðils' lessons were that under Icelandic rule, the nation was prosperous, productive and artistic, but suffered under foreign role. However, Aðils argued that within every Icelander, a desire for freedom and nationalism remained, and only had to be awoken.[3] Historian Guðmundur Hálfdanarson suggests that Aðils himself was doing his best to awaken this slumbering nationalist sentiment and strengthen the Icelandic pursuit of independence.[5]

According to Icelandic historian Axel Kristinsson, there is little historical evidence to substantiate the aforementioned traditional narrative about economic decline after the Saga age.[6][7] The Icelandic historian Árni Daníel Júlíusson characterizes the period 1550-1800 as a golden age in Icelandic farming.[8] However, a 2009 book by the Icelandic historian Gunnar Karlsson supports the decline thesis, as he shows a 40% reduction in GDP from the 12th century to the 18th century.[9] The Danish anthropologist Kirsten Hastrup characterizes the period 1400-1800 as a "period of remarkable social disintegration and technological decline."[10]

18th to 20th century

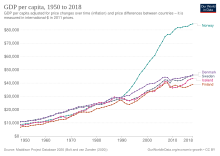

editIceland had among the lowest GDP per capita in Western Europe at the start of the 20th century.[11][12] According to one assessment by Central Bank of Iceland economists,

Post-World War II economic growth has been both significantly higher and more volatile than in other OECD countries. The average annual growth rate of GDP from 1945 to 2007 was about 4%. Studies have shown that the Icelandic business cycle has been largely independent of the business cycle in other industrialised countries. This can be explained by the natural resource-based export sector and external supply shocks. However, the volatility of growth declined markedly towards the end of the century, which may be attributed to the rising share of the services sector, diversifi cation of exports, more solid economic policies, and increased participation in the global economy.[11]

According to Reuters, Iceland has had "over 20 financial crises since 1875".[13]

Agricultural modernization

editCertain institutional arrangements in Iceland retarded the modernization of agriculture and the growth of non-agrarian sectors.[14] One such institution was "the system of land tenures with its heavy obligations to landlords and insecure farm leases, which discouraged fixed capital investment on the farms. The other was a wide-ranging social legislation set up to regulate family formations and to maintain a balance between agriculture and the fishing sector in favour of the former. The most effective regulatory device was a stringent labour bondage which had few parallels in Europe."[14]

In the early 20th century, there was a decline in rowing boat fishing as the fishing industry moved towards mechanized fishing vessels.[6]

Prior to 1880, agriculture (in particular, sheep products) was the largest share of Icelandic exports.[15]

Urbanization

editAccording to University of Iceland economists Davíd F. Björnsson and Gylfi Zoega, "The policies of the colonial masters in Copenhagen delayed urbanisation. The Danish king maintained a monopoly in trade with Iceland from 1602 until 1855, which made the price of fish artificially low – the price of fish was higher in Britain – and artificially raised the price of agricultural products. Instead, Denmark bought the fish caught from Iceland at below world market prices. Although the trade monopoly ended in 1787, Icelanders could not trade freely with other countries until 1855. Following trade liberalisation, there was a substantial increase in fish exports to Britain, which led to an increase in the number of sailing ships, introduced for the first time in 1780. The growth of the fishing industry then created demand for capital, and in 1885 Parliament created the first state bank (Landsbanki). In 1905 came the first motorised fishing vessel, which marked an important step in the development of a specialised fishing industry in Iceland. Iceland exported fresh fish to Britain and salted cod to southern Europe, with Portugal an important export market. Fishing replaced agriculture as the country’s main industry. These developments set the stage for the urbanisation that was to follow in the twentieth century."[16]

Food consumption

editA 1998 study found that food consumption patterns differed from those in the rest of Europe: "The prominence of domestically produced dairy products, fish, meat and suet, and the insignificance of cereals until the nineteenth century, are among the most unusual features."[17]

Growth of the fisheries sector

editAfter 1880, fish products were the largest share of Icelandic exports.[15] The fisheries sector in Iceland grew in part due to expanded fishing with sailing smacks. With the mechanization of the fishing fleet, which began primarily in 1905, fishing became an overwhelmingly large part of the Icelandic economy.[18]

World War I

editIn the quarter of a century preceding the War, Iceland prospered. Iceland became more isolated during World War I and suffered a significant decline in living standards.[19][20] The treasury became highly indebted, there was a shortage of food and fears over an imminent famine.[19][20][21]

Iceland traded significantly with the United Kingdom during the War, as Iceland found itself within its sphere of influence.[22][23][24] In their attempts to stop the Icelanders from trading with the Germans indirectly, the British imposed costly and time-consuming constraints on Icelandic exports going to the Nordic countries.[23][25]

The War led to major government interference in the marketplace that would last until the post-World War II period.[26]

The Great Depression

editIcelandic post-World War I prosperity came to an end with the outbreak of the Great Depression, a severe worldwide economic depression. The Depression hit Iceland hard as the value of exports plummeted. The total value of Icelandic exports fell from 74 million kronur in 1929 to 48 million in 1932, and was not to rise again to the pre-1930 level until after 1939.[27] Government interference in the economy increased: "Imports were regulated, trade with foreign currency was monopolized by state-owned banks, and loan capital was largely distributed by state-regulated funds".[27] Due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, which cut Iceland's exports of saltfish by half, the Depression lasted in Iceland until the outbreak of World War II when prices for fish exports soared.[27]

World War II

editThe British and American occupations of Iceland caused an end to unemployment, and contributed to the end of the Great Depression in Iceland. The occupiers injected money into the Icelandic economy and launched various projects.[28][29] This eradicated unemployment in Iceland and raised wages considerably.[28][29] According to one study, "by the end of World War II, Iceland had been transformed from one of Europe’s poorest countries to one of the world’s wealthiest."[28]

1945–1960

editIceland remained relatively protectionist during the period 1945–1960, despite its participation in the OEEC's Trade Liberalisation Program (TLP).[30][28] Economic historian Guðmundur Jónsson attributes Icelandic protectionism in the post-WWI period to the "external shock caused by the war, creating an artificial economy internally and the overvaluation of the krona, made adjustment to peacetime circumstances extremely difficult. The task was made harder by a public policy prioritizing on growth and investment rather than balanced macroeconomic management. Last but not least, Iceland's commercial interests were not easily reconcilable with those of the other members of the OEEC because of her special pattern of trade."[30]

In the period 1945–1960, the United States provided extensive economic assistance to Iceland.[29][31][28] Iceland received the largest Marshall Aid package per capita in the period 1948-1951 (even though Iceland was left relatively unscathed from World War II), almost twice as much as the second highest recipient.[32][29] Later in the 1950s, Iceland received direct economic assistance from the United States in what University of Iceland historian Valur Ingimundarson has referred to as the equivalent of a "second Marshall aid" package.[31]

From 1951 to 2006, the Iceland Defense Force provided between 2% and 5% of Iceland's GDP.[29]

1980s

editThe Icelandic economy was in an upswing in the mid-1980s.[33] In 1987, the tax rates were temporarily reduced to zero.[33][34]

1990s

editIn 1991, the Independence Party, led by Davíð Oddsson, formed a coalition government with the Social Democrats. This government set in motion market liberalisation policies, privatising a number of small and large companies. At the same time economic stability increased and previously chronic inflation was drastically reduced.[citation needed] In 1995, the Independence Party formed a coalition government with the Progressive Party. This government continued with the free-market policies, privatising two commercial banks and the state-owned telecom Síminn. Corporate incomes tax was reduced to 18% (from around 50% at the beginning of the decade), inheritance tax was greatly reduced and the net wealth tax abolished.[citation needed] "Nordic Tiger" was a term used to refer to the period of economic prosperity in Iceland that began in the post-Cold-War 1990s.[35]

The welfare state

editThe social expenditure as a percentage of GDP in Iceland lagged considerably behind the social expenditures in the other Nordic states during the 20th century.[36] There are two primary reasons in the academic literature for why Iceland lagged behind:

- "The absence of a strong social democratic party" - Whereas labor unions were fairly strong in Iceland, votes on the left were split between several leftist parties, which meant that the leftist tendencies did not translate into political power.

- "A stronger emphasis on individualism and self-help"[36]

21st century

editIcelandic financial crisis

editThe "Nordic Tiger" period ended in a national financial crisis in 2008, when the country's major banks failed and were taken over by the government. Iceland went from the fourth richest country in the world (GDP per capita) in 2007 to the 21st place in 2010.[37] According to a 2011 study, Iceland privatized its banks in the early 2000s and the rapid expansion of the banking system, coupled with Iceland's small size, meant that the central bank was incapable of serving as the lender of last resort if a crisis were to occur.[38] The banks made risky loans and manipulated markets.[38] Iceland's regulators and public institutions were weak and understaffed, and were thus not properly regulating or supervising the banks.[38] Political connections between senior bank managers, key shareholders and elite politicians meant that there was insufficient will to properly regulate the banks.[38]

Following sharp inflation in the Icelandic króna during 2008, the three major banks in Iceland, Glitnir, Landsbanki and Kaupthing were placed under government control. A subsidiary of Landsbanki, Icesave, which operated in the UK and the Netherlands, was declared insolvent, putting the savings of thousands of UK and Dutch customers at risk.[39] It also transpired that over 70 local authorities in the UK held more than £550 million of cash in Icelandic banks.[40][41] In response to statements that the accounts of UK depositors would not be guaranteed, the British governments seized assets of the banks and of the Icelandic government.[citation needed][42] On 28 October 2008, Iceland's central bank raised its interest rate to 18 per cent to fight inflation.[43]

The Ice-save dispute, coupled with belated IMF assistance and no direct economic assistance from Iceland's close Cold War ally the United States, indicated that Iceland was left without "shelter", according to the 2018 book Small States and Shelter Theory: Iceland’s External Affairs by University of Iceland political scientists.[29] The Icelandic government was under the impression that Iceland would receive extensive assistance from the United States, similar to the aid that Iceland repeatedly got in economic crises during the Cold War.[29] University of Iceland political scientist Baldur Thorhallsson has argued that Iceland received belated assistance from the IMF relative to Ireland (which was also undergoing a financial crisis) because Iceland was not a member of the EU and euro (unlike Ireland).[44]

Following negotiations with the IMF,[45] a package of $4.6 billion was agreed on 19 November, with the IMF loaning $2.1 billion and another $2.3 billion in loans and currency swaps from Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark. In addition, Poland has offered to lend $200 million and the Faroe Islands have offered 300 million Danish kroner ($50 million, about 3 per cent of Faroese GDP).[46] The next day, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom announced a joint loan of $6.3 billion (€5 billion), related to the deposit insurance dispute.[47][48] The assistance bolstered the Central Bank of Iceland's foreign currency reserves, which was an important first step in the economic recovery.[37] By the end of 2015, Iceland had repaid all the loans that it received in relation to the IMF program.[49] The IMF did not impose the kind of strict conditions on the assistance as it had done in similar past situations in Asia and Latin America. According to economists Ásgeir Jónsson and Hersir Sigurjónsson, "Iceland was treated differently from developing countries and former IMF clients. There was no call for Iceland to adopt sharp austerity measures at the inception of the joint economic plan. Instead, the government would be allowed to maintain large public deficits in the first year – 2009 – allowing fiscal multipliers to counteract the output contraction that was underway. Iceland also was not asked to downsize its Scandinavian-type welfare system."[50]

Iceland is the only country in the world to have a population under two million yet still have a floating exchange rate and an independent monetary policy.[51]

References

edit- ^ Jónsson, Guðmundur (1 September 2002). "Icelandic economic history: A historiographical survey of the last century". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 50 (3): 44–56. doi:10.1080/03585522.2002.10410817. ISSN 0358-5522. S2CID 154932284.

- ^ Mehler, Natascha; Gardiner, Mark (2021), Coinless exchange and foreign merchants in medieval Iceland (AD 900-1600), Hamburg: Wachhotz Verlag, pp. 35–54, doi:10.23797/9783529035418, hdl:1887/3196654, ISBN 978-3-529-03541-8, S2CID 243630241

- ^ a b c "Land og saga - Íslenzkt þjóðerni. Eftir Jón J. Aðils". landogsaga.is. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Bergmann, Eiríkur (1 March 2014). "Iceland: A postimperial sovereignty project". Cooperation and Conflict. 49 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1177/0010836713514152. ISSN 0010-8367. S2CID 154972672.

- ^ Hálfdanarson (2010). "Sagan og sjálfsmynd(ir) íslenskrar þjóðar". Glíman.

- ^ a b Kristinsson, Axel (2018). Hnignun, hvaða hnignun? Goðsögnin um niðurlægingartímabilið í sögu Íslands. Sögufélag.

- ^ Kjartansson, Helgi Skúli (18 November 2019). "Axel Kristinsson, Hnignun, hvaða hnignun? Goðsögnin um niðurlægingartímabilið í sögu Íslands [Decline, What Decline? The Myth of the Depressed Era in the History of Iceland]. (Reykjavík: Sögufélag 2018). 280 pp". 1700-tal. 16: 149–151–149–151. doi:10.7557/4.4890. ISSN 2001-9866.

- ^ Júlíusson 1959, Árni Daníel (1997). Bønder i pestens tid. Landbrug, godsdrift og social konflikt i senmiddelalderens islandske bondesamfund (Thesis thesis) (in Danish).

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Karlsson, Gunnar (2009). Lífsbjörg Íslendinga. Háskólaútgáfan.

- ^ Hastrup, Kirsten (1995). Nature and Policy in Iceland 1400-1800. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827728-6.

- ^ a b "Economy of Iceland 2008".

- ^ Jónsson, Guðmundur (1999). Hagvöxtur og iðnvæðing. Þjóðarframleiðsla á Íslandi 1870–1945.

- ^ Jones, Maiya Keidan and Marc. "Red hot Iceland keeps some investors out in the cold". Reuters UK. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ a b Jónsson, Gudmundur (1 May 1993). "Institutional change in Icelandic agriculture, 1780–1940". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 41 (2): 101–128. doi:10.1080/03585522.1993.10415863. ISSN 0358-5522.

- ^ a b Júlíusson, Árni Daníel (2 August 2020). "Agricultural growth in a cold climate: the case of Iceland in 1800–1850". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 69 (3): 217–232. doi:10.1080/03585522.2020.1788985. ISSN 0358-5522. S2CID 225502730.

- ^ Björnsson, Davíd F.; Zoega, Gylfi (26 June 2017). "Seasonality of birth rates in agricultural Iceland" (PDF). Scandinavian Economic History Review. 65 (3): 294–306. doi:10.1080/03585522.2017.1340333. ISSN 0358-5522. S2CID 157474068.

- ^ Jonsson, Gudmundur (1 January 1998). "Changes in food consumption in Iceland, 1770–1940". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 46 (1): 24–41. doi:10.1080/03585522.1998.10414677. ISSN 0358-5522.

- ^ JÓnsson, SigfÚs (1 July 1983). "The Icelandic fisheries in the pre-mechanization Era, C. 1800–1905: Spatial and economic implications of growth". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 31 (2): 132–150. doi:10.1080/03585522.1983.10408006. ISSN 0358-5522.

- ^ a b Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 16.

- ^ a b Jónsson, Guðmundur (1999). Hagvöxtur og iðnvæðing. Þjóðarframleiðsla á Íslandi 1870–1945.

- ^ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. Ch. 12.

- ^ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 148.

- ^ a b Jensdóttir, Sólrún (1980). Ísland á bresku valdssvæði 1914-1918.

- ^ Thorhallsson, Baldur; Joensen, Tómas (15 December 2015). "Iceland's External Affairs from the Napoleonic Era to the occupation of Denmark: Danish and British Shelter". Icelandic Review of Politics & Administration. 11 (2): 187–206. doi:10.13177/irpa.a.2015.11.2.4. ISSN 1670-679X.

- ^ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. pp. 173–175.

- ^ Bjarnason, Gunnar Þór (2015). Þegar siðmenningin fór til fjandans. Íslendingar og stríðið mikla 1914-1918. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). History of Iceland. pp. 308–312.

- ^ a b c d e Steinsson, Sverrir (2018). "A Theory of Shelter: Iceland's American Period (1941–2006)". Scandinavian Journal of History. 43 (4): 539–563. doi:10.1080/03468755.2018.1467078. S2CID 150053547.

- ^ a b c d e f g Thorhallsson, Baldur, ed. (2018). "Small States and Shelter Theory: Iceland's External Affairs". Routledge.

- ^ a b Jónsson, Gudmundur (1 May 2004). "Iceland, OEEC and the trade liberalisation of the 1950s". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 52 (2–3): 62–84. doi:10.1080/03585522.2004.10405252. ISSN 0358-5522. S2CID 153561720.

- ^ a b Ingimundarson, Valur (2011). The Rebellious Ally: Iceland, the United States, and the Politics of Empire 1945-2006. Republic of Letters. ISBN 9789089790699.

- ^ Jonsson, Guðmundur; Snævarr, Sigurður (2008). "Iceland's Response to European Economic Integration". Pathbreakers: Small European Countries Responding to Globalisation and Deglobalisation. Peter Lang. p. 385.

- ^ a b Bianchi, Marco; Gudmundsson, Björn R; Zoega, Gylfi (1 December 2001). "Iceland's Natural Experiment in Supply-Side Economics". American Economic Review. 91 (5): 1564–1579. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.607.5800. doi:10.1257/aer.91.5.1564. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 44587964.

- ^ Ólafsdóttir, Thorhildur; Hrafnkelsson, Birgir; Thorgeirsson, Gudmundur; Ásgeirsdóttir, Tinna Laufey (1 September 2016). "The tax-free year in Iceland: A natural experiment to explore the impact of a short-term increase in labor supply on the risk of heart attacks". Journal of Health Economics. 49: 14–27. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.06.006. ISSN 1879-1646. PMID 27372576.

- ^ Global freeze kills Nordic tiger Archived 5 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Age, 11 October 2008.

- ^ a b Schouenborg, Laust (2012). "The Scandinavian International Society: Primary Institutions and Binding Forces, 1815-2010". Routledge.

- ^ a b Benediktsdóttir, Sigríður; Eggertsson, Gauti B.; Þórarinsson, Eggert (November 2017). "The Rise, the Fall, and the Resurrection of Iceland". NBER Working Paper No. 24005. doi:10.3386/w24005.

- ^ a b c d Benediktsdottir, Sigridur; Danielsson, Jon; Zoega, Gylfi (1 April 2011). "Lessons from a collapse of a financial system". Economic Policy. 26 (66): 183–235. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.185.4714. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00260.x. ISSN 0266-4658. S2CID 153628546.

- ^ "Icesave savers warned on accounts". BBC News. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ "Councils fear for Icelandic cash". BBC News. 10 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ "PACIFIC Exchange Rate Service".

- ^ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/2668/article/4/made.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Iceland's interest rate soars to 18% Archived 24 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, ITN News, 8 October 2008.

- ^ Thorhallsson, Baldur; Kirby, Peadar (2012). "Financial Crises in Iceland and Ireland: Does European Union and Euro Membership Matter?". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 50 (5): 801–818. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02258.x. ISSN 1468-5965. S2CID 154684615.

- ^ "Press Release: IMF Announces Staff Level Agreement with Iceland on US$2.1 Billion Loan".

- ^ Brogger, Tasneem; Einarsdottir, Helga Kristin (20 November 2008). "Iceland Gets $4.6 Billion Bailout From IMF, Nordics". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ "Dutch €1.3bn loan to Iceland agreed". DutchNews. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (20 November 2008). "UK Treasury lends Iceland £2.2bn to compensate Icesave customers". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Jónsson, Ásgeir; Sigurgeirsson, Hersir (2016). The Icelandic Financial Crisis - A Study into the World´s Smallest Currency Area and its Recovery from Total Banking Collapse. Palgrave. p. 146. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-39455-2. ISBN 978-1-137-39454-5.

- ^ Jónsson, Ásgeir; Sigurgeirsson, Hersir (2016). The Icelandic Financial Crisis - A Study into the World´s Smallest Currency Area and its Recovery from Total Banking Collapse. pp. 216–217. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-39455-2. ISBN 978-1-137-39454-5.

- ^ "Aðildarviðræður Íslands við ESB" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

Further reading

edit- Lárusson, Björn (1961). "Valuation and distribution of landed property in Iceland". Economy and History. 4: 34–64. doi:10.1080/00708852.1961.10418982.

- Blöndal, Gísli (1969). "The growth of public expenditure in Iceland". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 17: 1–22. doi:10.1080/03585522.1969.10407656.

- Guðmundur Jónsson. 2004. "The transformation of the Icelandic economy: Industrialization and economic growth, 1870-1950." In Exploring Economic Growth: Essays in Measurement and Analysis. A Feistschrift For Riitta Hjerpe on Her 60th Birthday (eds, S. Heikkinen and J. L. von Zanden). Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers.

- Guðmundur Jónsson. 2009. "Efnahagskreppur á Íslandi 1870-2000." Saga.

- Nielsson, Ulf; Torfason, Bjarni K. (2012). "Iceland's economic eruption and meltdown". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 60: 3–30. doi:10.1080/03585522.2012.651303. S2CID 154516898.

- Gylfason, Thorvaldur, Bengt Holmström, Sixten Korkman, Hans Tson Söderström, and Vesa Vihriälä (2010), "Nordics in Global Crisis – Vulnerability and Resilience”, ETLA, Helsinki Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Zoega, Gylfi (2017). "Nordic Lessons from Exchange Rate Regimes". Atlantic Economic Journal. 45 (4): 411–428. doi:10.1007/s11293-017-9555-5. S2CID 158837914.

2008 financial crisis and recovery

- Ásgeir Jónsson and Hersir Sigurjónsson. 2016. The Icelandic Financial Crisis A Study into the World´s Smallest Currency Area and its Recovery from Total Banking Collapse. Palgrave.

- Fridrik Mar Baldursson and Richard Portes. 2013. Gambling for Resurrection in Iceland: The Rise and Fall of the Banks. Working paper. SSRN 2361098

- Guðrún Johnsen. 2014. Bringing Down the Banking System. Palgrave.

- Már Guðmundsson. 2016. Iceland’s recovery: Facts, myths, and the lessons learned, speech on 28 January 2016.

- Robert Z. Aliber and Gylfi Zoega (eds.). 2011. Preludes to the Icelandic Financial Crisis. Palgrave.

- Benediktsdóttir, Sigríður; Eggertsson, Gauti B.; Þórarinsson, Eggert (2017). "The Rise, the Fall, and the Resurrection of Iceland". NBER Working Paper. 24005. doi:10.3386/w24005.

- Benediktsdóttir, Sigríður; Danielsson, Jón; Zoega, Gylfi (2011). "Lessons from a collapse of a financial system". Economic Policy. 26 (66): 183–235. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00260.x. S2CID 153628546.