William Allen Jowitt, 1st Earl Jowitt, PC, KC (15 April 1885 – 16 August 1957) was a British Liberal Party, National Labour and then Labour Party politician and lawyer who served as Lord Chancellor under Clement Attlee from 1945 to 1951.

The Earl Jowitt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

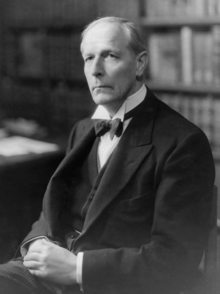

Jowitt in 1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 July 1945 – 26 October 1951 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George VI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Viscount Simon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Lord Simonds | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords Shadow Leader of the House of Lords | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1952 – 14 December 1955 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party Leader | Clement Attlee Herbert Morrison (acting) Hugh Gaitskell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Viscount Addison | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl Alexander of Hillsborough | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 15 April 1885 Stevenage, Hertfordshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 August 1957 (aged 72) Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Lesley McIntyre (m. 1913) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background and education

editHe was born in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, the son of Reverend William Jowitt, Rector of Stevenage, by his wife Louisa Margaret Allen.

At the age of nine, he was sent to Northaw Place, a preparatory school in Potters Bar, Middlesex, where he first met and was looked after by fellow student Clement Attlee, the future Labour Party Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

From Northaw, he went to Marlborough College, then to New College, Oxford where he studied law. He was admitted to the Middle Temple on 15 November 1906 and was called to the Bar on 23 June 1909.[1]

Legal and political career (1922–1931)

editJowitt became a member of chambers in Brick Court in London. He proved himself a skilled advocate, attracting attention for his subdued and charming manner when barristers were more inclined to browbeat witnesses. He became a King's Counsel the day before the 1922 general election in which he was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for The Hartlepools. Jowitt was a member of the faction of the Liberal Party led by H. H. Asquith and somewhat radical in his beliefs. He continued to practise law whilst a backbench MP and was not considered a great orator in the House of Commons.

Jowitt was re-elected, now part of the re-united Liberal Party, at the 1923 general election, and in 1924, he was a member of the Royal Commission on Lunacy. He lost his seat in the 1924 general election. Jowitt stood successfully in Preston in the 1929 general election, again elected as a Liberal. Following the formation of a minority Labour government, he was offered the position of attorney general by the new prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald.

Labour had few experienced lawyers in its ranks in Parliament and had experienced problems filling the positions of legal officers in its first government. Jowitt agreed, but resigned his seat and stood again as a candidate for the Labour Party. At the by-election in July 1929, Preston re-elected him with an increased majority. As was customary, Jowitt received a knighthood upon becoming attorney general. His work mainly concerned the drafting of government bills, particularly the reversal of the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927.

As was still the custom for the attorney general, he occasionally prosecuted in high-profile cases, notably Sidney Harry Fox, charged with murdering his mother by suffocating her and then setting fire to her hotel room. It was said that a single question from Jowitt ("Explain to me why you shut the door?") sealed Fox's fate since Fox could think of no convincing answer.

Divided loyalties (1931–1939)

editWhen the Labour government split over the financial crisis in 1931, Jowitt was one of only a handful of Labour MPs to follow MacDonald into the National Government. He was uncomfortable in a coalition with the Conservatives but believed that the proposed spending cuts causing the split were necessary, and the coalition was necessary to force them through. Like others who joined the National Government, he was expelled from the Labour Party.

He was made a Privy Councillor but found himself in a difficult electoral position when he could not secure the withdrawal of the Conservative candidate in Preston in the 1931 general election. He thus stood instead as the National Labour candidate for the Combined English Universities, but there too, he competed with other candidates supporting the National Government and was defeated. MacDonald persuaded Jowitt to remain as Attorney General in the hope that a new seat could be found to maintain the handful of National Labour positions in the government, but that proved impossible and Jowitt stepped down. He was replaced as Attorney General in January 1932 and returned to the Bar. Though relatively new to the party, Jowitt greatly regretted the split with Labour. He remained close to MacDonald, but after Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister in 1935, Jowitt began campaigning for Labour.

A number of constituency Labour Parties attempted to nominate him as their candidate for the general election that year, but he was still expelled. Unable to stand for Labour, he refused to stand for any other party or as an independent.

Jowitt was readmitted to the Labour Party in November 1936. Still a public figure, he was a critic of the National Government's policy of appeasement, and in 1937, he called for the state control of the arms industry and rapid rearmament to face the growing threat of fascism on the Continent.

In February 1939 he called for the recreation of the Ministry of Munitions. In October, he was adopted as Labour's candidate at a by-election in Ashton-under-Lyne and was elected unopposed, due to the war-time electoral pact.[2]

Churchill ministry (1940–1945)

editEight months later, Winston Churchill appointed Jowitt as Solicitor General in his coalition government. Jowitt dispensed legal advice to the government for two years in World War II before he was placed in charge of planning for reconstruction. He also held Cabinet positions that were mostly sinecures such as Paymaster General and then Minister without Portfolio in that role.

In 1944, he became Minister of National Insurance at the head of a new government department. He resigned from the government when Labour left the coalition in May 1945, after Victory in Europe Day, and he was re-elected for Ashton-under-Lyne in the general election in July.

Lord Chancellor (1945–1951)

editAfter a landslide victory in the 1945 election, Labour formed its first majority government. Prime Minister Clement Attlee appointed Jowitt as Lord Chancellor. As soon as he was appointed, Jowitt met with US Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson to resolve outstanding points of contention over the draft London Charter, which would govern the procedures of the Nuremberg Trials. He retained the Conservative MP and outgoing Attorney General, Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, as the official liaison but indicated that the new Attorney General, Sir Hartley Shawcross, would serve as Britain's Chief Prosecutor in the trials themselves.

Jowitt introduced and saw signed the United Nations Act 1946, the legislation that governs how the UK subordinates itself to the UN.[3][4]

He was raised to the peerage as Baron Jowitt, of Stevenage in the County of Hertford, on 2 August 1945 and entered the House of Lords.[5] He led much important judicial legislation during the life of the Labour government.

Jowitt was also responsible for some key changes to the legal culture in Britain. He attempted to end political and social imbalances in the Magistrates Courts and is considered to have been the first Lord Chancellor to adopt a policy of appointing judges purely on the basis of merit.[citation needed]

As Lord Chancellor, he also served as speaker of the House of Lords, a delicate job given the Conservative majority in the Lords. Christopher Addison, Labour's leader in the Lords, died shortly after the party's defeat in the 1951 general election.

Labour was now in opposition, and Jowitt took over as leader of the Labour peers. He was created Viscount Jowitt, of Stevenage in the County of Hertford, on 20 January 1947,[6] and was awarded an earldom by Attlee in the 1951 Prime Minister's Resignation Honours,[7] being created Viscount Stevenage, of Stevenage in the County of Hertford and Earl Jowitt on 24 January 1952.[8]

Later political life

editA senior figure in the party, and a member of the Shadow Cabinet, Jowitt was careful to keep the Labour peers out of the conflict between the Bevanites and Gaitskellites in the early 1950s. The opposition to the Conservative government in the Lords was meagre but sometimes successfully rallied support from government backbenchers.

In 1955, for instance, Jowitt led a successful rebellion in the Lords over a government bill to criminalise the medical use of marijuana. Jowitt was a prominent spokesperson against human rights abuses during the suppression of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, teaming up with the Archbishop of Canterbury to launch a review of the circumstances surrounding the resignation of Colonel Arthur Young as Commissioner of Police in the colony.[9] He stood down as leader in November 1955, at the age of 70.

Family

editJowitt married Lesley McIntyre, a daughter of James Patrick McIntyre, in 1913. He died at Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, in August 1957, aged 72. His peerages did not survive his death, as he had no male heirs.

Publications

editJowitt wrote two books on espionage and compiled a legal dictionary, which was published posthumously in 1959, completed by Clifford Walsh, and became a standard reference work. It remains in print as Jowitt's Dictionary of English Law.[10]

- The Strange Case of Alger Hiss (1953. London: Hodder & Stoughton)

- Some Were Spies (1954. London: Hodder & Stoughton)

- Dictionary of English Law (1959. London: Sweet & Maxwell)

References

edit- ^ Williamson, J.B. (1937). The Middle Temple Bench Book. 2nd edition, p. 290.

- ^ Kay Halle, The Irrepressible Churchill, (Robson Books, 1966), 44

- ^ supremecourt.uk: HM Treasury v Ahmad, etc, 27 Jan 2010

- ^ Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 139. House of Lords. 12 February 1946. col. 373.

- ^ "No. 37208". The London Gazette. 3 August 1945. p. 3981.

- ^ "No. 37860". The London Gazette. 21 January 1947. p. 411.

- ^ The Times, Friday, 30 November 1951; pg. 6; Issue 52172; col G: "The Resignation Honours: Earldom For Lord Jowitt"

- ^ "No. 39433". The London Gazette. 4 January 1952. p. 136.

- ^ Elkins, C. (2005) Britain's Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya, Pimlico: London

- ^ London: Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 9780414051140