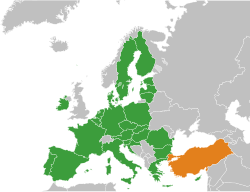

Relations between the European Union (EU) and Turkey were established in 1959, and the institutional framework was formalized with the 1963 Ankara Agreement. Albeit not officially part of the European Union, Turkey is one of the EU's main partners and both are members of the European Union–Turkey Customs Union. Turkey borders two EU member states: Bulgaria and Greece.

| |

European Union |

Turkey |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Delegation of the European Union to Turkey, Ankara | Turkish permanent mission to the European Union, Brussels |

Turkey has been an applicant to accede to the EU since 1987,[1][2] but since 2016 accession negotiations have stalled.[3] The EU has criticised Turkey for human rights violations and deficits in rule of law.[4][5] In 2017, EU officials expressed the view that planned Turkish policies violate the Copenhagen criteria of eligibility for EU membership.[6] On 26 June 2018, the EU's General Affairs Council noted that "Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union. Turkey's accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing and no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen."[7][8]

Background

editAfter the Ottoman Empire's collapse following World War I, Turkish revolutionaries led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk emerged victorious in the Turkish War of Independence, establishing the modern Turkish Republic as it exists today. Atatürk, President of Turkey, implemented a series of reforms, including secularisation and industrialisation, intended to "Europeanise" or Westernise the country.[9] During World War II, Turkey remained neutral until February 1945, when it joined the Allies. The country took part in the Marshall Plan of 1947, became a member of the Council of Europe in 1950,[10] and a member of NATO in 1952.[11] During the Cold War, Turkey allied itself with the United States and Western Europe. The Turkish expert Meltem Ahıska outlines the Turkish position vis-à-vis Europe, explaining how "Europe has been an object of desire as well as a source of frustration for Turkish national identity in a long and strained history".[12]

Foreign relations policies of the Republic of Turkey have – based on the Western-inspired reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – placed heavy emphasis on Turkey's relationship with the Western world, especially in relation to the United States, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union. The post-Cold War period has seen a diversification of relations, with Turkey seeking to strengthen its regional presence in the Balkans, the Middle East and the Caucasus, as well as its historical goal of EU membership. Under the AKP government, Turkey's influence has grown in the Middle East based on the strategic depth doctrine, also called Neo-Ottomanism.[13][14] Debate on Turkey in the West is sharply divided between those who see Turkey moving away from the West toward a more Middle Eastern and Islamic orientation and those who see Ankara's improved ties with its Islamic neighbors as a natural progression toward balance and diversification.[15]

History of relations

editTurkey was one of the first countries, in 1959, to seek close cooperation with the young European Economic Community (EEC). This cooperation was realised in the framework of an association agreement, known as the Ankara Agreement, which was signed on 12 September 1963. An important element in this plan was establishing a customs union so that Turkey could trade goods and agricultural products with EEC countries without restrictions. The main aim of the Ankara agreement was to achieve "continuous improvement in living conditions in Turkey and in the European Economic Community through accelerated economic progress and the harmonious expansion of trade, and to reduce the disparity between the Turkish economy and … the Community".

Accession of Turkey to the European Union

editEnlargement is one of the EU's most powerful policy tools. It is a carefully managed process which helps the transformation of the countries involved, extending peace, stability, prosperity, democracy, human rights and the rule of law across Europe. The European Union enlargement process took a bold step on 3 October 2005 when accession negotiations were opened with Croatia (an EU member since 2013) and Turkey. After years of preparation the two candidates formally opened the next stage of the accession process. The negotiations relate to the adoption and implementation of the EU body of law, known as the acquis. The acquis is approximately 130,000 pages of legal documents grouped into 35 chapters and forms the rules by which Member States of the EU should adhere. As a candidate country, Turkey needs to adapt a considerable part of its national legislation in line with EU law. This means fundamental changes for society that will affect almost all sectors of the country, from the environment to the judiciary, from transport to agriculture, and across all sections of the population. However, the candidate country does not 'negotiate' on the acquis communautaire itself as these 'rules' must be fully adopted by the candidate country. The negotiation aspect is on the conditions for harmonisation and implementation of the acquis, that is, how the rules are going to be applied and when. It is for this reason that accession negotiations are not considered to be negotiations in the classical sense. In order to become a Member State, the candidate country must bring its institutions, management capacity and administrative and judicial systems up to EU standards, both at national and regional level. This allows them to implement the acquis effectively upon accession and, where necessary, to be able to implement it effectively in good time before accession. This requires a well-functioning and stable public administration built on an efficient and impartial civil service, and an independent and efficient judicial system. EU–Turkey relations deteriorated following President Erdoğan's crackdown on supporters of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt. Erdoğan has indicated that he approves of reinstating the death penalty to punish those involved in the coup, and the EU has stated that it will formally end accession negotiations with Turkey if the death penalty is reinstated.[16] On 25 July 2016, President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker said that Turkey was not in a position to become a member of the European Union in the near future and that accession negotiations between the EU and Turkey would be stopped immediately if the death penalty was brought back.[17] On 24 November 2016 the European Parliament voted to suspend accession negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns;[18] however, this decision was non-binding.[19] On 13 December, the European Council (comprising the heads of state or government of the member states) resolved that it would open no new areas in Turkey's membership talks in the "prevailing circumstances",[20] as Turkey's path toward autocratic rule makes progress on EU accession impossible.[21]

In 2016, EU member Austria opposed Turkey's EU membership.[22] In March 2018, then-Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz opposed Turkey's EU accession talks and urged it to halt membership talks.[23]

In 2017, EU officials expressed that planned Turkish policies violate the Copenhagen criteria of eligibility for an EU membership.[6] On 6 July 2017, the European Parliament unanimously accepted the call for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey.[24] On 26 June 2018, the EU's General Affairs Council stated that "the Council notes that Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union. Turkey's accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing and no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen." The Council added that it is "especially concerned about the continuing and deeply worrying backsliding on the rule of law and on fundamental rights including the freedom of expression."[7][8][25] On 13 March 2019, the European Parliament unanimously accepted the call for a halt to the full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey.[26] On 19 May 2021, the European Parliament unanimously accepted the call for the suspension of accession negotiations between the EU and Turkey.[27] However, in July 2023, Erdoğan brought up Turkey's accession to EU membership in the context of Sweden's application for NATO membership.[28] On 18 July 2023, the EU decided not to restart full membership negotiations with Turkey.[29] According to Dagens Nyheter's data, in September 2023, 60% of Swedes said that Sweden opposes Turkey's EU membership and will not support the membership process, while 7% said that Sweden does not oppose Turkey's EU membership and will support the membership process.[30]

- Key milestones

- 1963: The association agreement is signed between Turkey and the EEC.

- 1987: Turkey submits application for full membership.

- 1993: The EU and Turkey Customs Union negotiations start.

- 1996: The Customs Union between Turkey and the EU takes effect.

- 1999: At the Helsinki Summit, the European Council gives Turkey the status of candidate country for EU membership, following the Commission's recommendation in its second Regular Report on Turkey.

- 2001: The European Council adopts the EU-Turkey Accession Partnership, providing a road map for Turkey's EU accession process. The Turkish Government adopts the NPAA, the National Programme for the Adoption of the Acquis, reflecting the Accession Partnership. At the Copenhagen Summit, the European Council decides to significantly increase EU financial support through what is now called the "pre-accession instrument" (IPA).

- 2004: The European Council decides to open accession negotiations with Turkey.

- 2005: Accession negotiations open.

- 2016: The European Parliament votes to suspend accession negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns.

- 2017: The EU parliament unanimously accepted the call for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey.

- 2018: The EU's General Affairs Council states that "Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union. Turkey's accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing and no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen."[31]

- 2019: The European Parliament unanimously accepted the call for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey.

- 2021: The European Parliament unanimously accepted the call for the suspension of accession negotiations between the EU and Turkey.[27]

Institutional cooperation

editThe association agreement that Turkey has with the EU serves as the basis for implementation of the accession process. Several institutions have been set up to ensure political dialogue and cooperation throughout the membership preparation process.

Association Council

The Council is made up of representatives of the Turkish government, the European Council and the European Commission. It is instrumental in shaping and orienting Turkey-EU relations. Its aim is to implement the association agreement in political, economic and commercial issues. The Association Council meets twice a year at ministerial level. The Council takes decisions unanimously. Turkey and the EU side have one vote each.

Association Committee

The Association Committee brings together experts from EU and Turkey to examine Association related technical issues and to prepare the agenda of the Association Council. The negotiations chapters are discussed in eight subcommittees organised as follows:

- Agriculture and Fisheries Committee

- Internal Market and Competition Committee

- Trade, Industry and ECSC Products Committee

- Economic and Monetary Issues Committee

- Innovation Committee

- Transport, Environment and Energy Committee

- Regional Development, Employment and Social Policy Committee

- Customs, Taxation, Drug Trafficking and Money Laundering Committee

Joint Parliamentary Commission

The Joint Parliamentary Commission is the control body of the Turkey-EU association. Its task is to analyze the annual activity reports submitted to it by the Association Council and to make recommendations on EU-Turkey Association related issues.

It consists of 18 members selected from the Turkish Grand National Assembly and the European Parliament, who meet twice a year.

Customs Union Joint Committee

The main task of the Customs Union Joint Committee (CUJC) is to establish a consultative procedure in order to ensure legislative harmony foreseen in the fields directly related to the functioning of the customs union between Turkey and the EU. The CUJC makes recommendations to the Association Council. It is planned to meet regularly once a month.

Joint Consultative Committee

The Joint Consultative Committee (JCC) was formed on 16 November 1995 in accordance with Article 25 of the Ankara Agreement. The Committee aims to promote dialogue and cooperation between the economic and social interest groups in the European Community and Turkey and to facilitate the institutionalisation of the partners of that dialogue in Turkey. The Joint Consultative Committee has a mixed, cooperative and two-winged structure, with EU and Turkey wings. It has 36 members in total, composed of 18 Turkish and 18 EU representatives and it has two elected co-chairmen, one from the Turkish side and the other from the EU side.

EU-related administrative bodies in Turkish administration

The Secretariat General for European Union Affairs was established in July 2000 to ensure internal coordination and harmony in the preparation of Turkey for EU membership.

The Under secretariat of Foreign Trade EU Executive Board was established to ensure the direction, follow-up and finalisation of work carried out within the scope of the Customs Union and the aim of integration.

Timeline of notable positions and statements

edit- In the 1920's, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, said that "there are different cultures, but only one civilisation," making it clear that he was not referring to Islamic civilisation: "We Turks have always gone from east to west."[32]

- In November 2002, the AKP led by later prime minister and president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was first elected into power, which it has held since. Islamist Erdoğan is infamous for the quote that "democracy is like a tram. We shall get out when we arrive at the station we want."[33][34]

- / In November 2002, then-French President and then-President of the European Convention Valéry Giscard d'Estaing said in an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde, "Turkey is an important country close to Europe, but it is not a European country. It is not a European country because its capital is not in Europe and 95% of its population lives outside Europe." he said. Estaing continued as follows: "The Union should now focus on internal financial problems and the construction of European harmony instead of expansion. Those who most support Turkey joining the Union are actually opponents of the European Union. In fact, the majority of European Council members are against Turkey joining, but the Turks were never told this. Turkey joining the European Union would mean the end of the European Union."[35]

- In January 2007, then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy stated that "Turkey has no place inside the European Union." Sarkozy continued, "I want to say that Europe must give itself borders, that not all countries have a vocation to become members of Europe, beginning with Turkey which has no place inside the European Union."[36]

- In July 2007, European Commission President José Manuel Barroso said that Turkey is not ready to join the EU "tomorrow nor the day after tomorrow", but its membership negotiations should continue. He also called on France and other member states to honour the decision to continue accession talks, describing it as a matter of credibility for the Union.[37][unreliable source?]

- In December 2010, then-President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy he said "Turkish reform efforts have delivered impressive results." He continued "Turkey plays an ever more active role in its neighbourhood. Turkey is also a full-standing member of the G-20, just like five EU countries and the EU itself. In my view, even before an outcome of the negotiations, the European Union should develop a close partnership with the Turkish Republic."[38]

- In September 2011, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has said on the occasion of the visit of the Turkish president Abdullah Gül: "We don't want the full membership of Turkey. But we don't want to lose Turkey as an important country", referring to her idea of a strategic partnership.[39]

- In June 2013, Turkey's Undersecretary of the Ministry of EU Affairs Haluk Ilıcak said, "The process means more than the accession. Once the necessary levels are achieved, Turkey is big enough to continue its development without the accession. Our aim is to achieve a smooth accession process."[40]

- During the 2014 European Parliament election campaign, presidential candidates Jean-Claude Juncker (EEP) and Martin Schulz (S&D) promised that Turkey would never join the European Union while either one of them were president, reasoning that Turkey had turned its back on European democratic values.[41] Juncker won the election and became the new president of the EU as of 1 November 2014. He later reaffirmed his stance:[42] "As regards Turkey, the country is clearly far away from EU membership. A government that blocks Twitter is certainly not ready for accession."

- In 2016, the EU made a deal with Turkey and decided to give Turkey €6 billion ($7.3 billion) the next period in order to help the country with the refugees and migrants living there (the contract ended in December 2020).[43]

- In March 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that democracy and freedom were "phrases" which had "absolutely no value" in Turkey, after calling for journalists, lawyers and politicians to be prosecuted as terrorists.[44]

- In May 2016, then-British Prime Minister David Cameron said that "it is not remotely on the cards that Turkey is going to join the EU any time soon. They applied in 1987. At the current rate of progress they will probably get round to joining in about the year 3000 according to the latest forecasts."[45]

- In July 2016, European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini announced that EU membership negotiations would be terminated if the death penalty was reinstated in Turkey.[46]

- In August 2016, then-Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern called for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey.[47]

- In March 2017, in a speech given to supporters in the western Turkish city of Sakarya, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said, "my dear brothers, a battle has started between the cross and the crescent", after insulting European government politicians as "Nazis" in the weeks before.[48] The same month, he threatened that Europeans would "not be able to walk safely on the streets" if they continued to ban Turkish ministers from addressing rallies in Europe.[5] European politicians rejected Erdoğan's comments.[49]

- In March 2017, Frank-Walter Steinmeier in his inaugural speech as President of Germany said that "the way we look (at Turkey) is characterized by worry, that everything that has been built up over years and decades is collapsing."[5]

- "Everybody's clear that, currently at least, Turkey is moving away from a European perspective," European Commissioner Johannes Hahn, who oversees EU membership bids, said in May 2017. "The focus of our relationship has to be something else. We have to see what could be done in the future, to see if we can restart some kind of cooperation."[4]

- In a TV debate in September 2017, then-German chancellor Angela Merkel and her challenger Martin Schulz both said that they would seek an end to Turkey's membership talks with the European Union.[50]

- In September 2017, Finnish foreign minister Timo Soini announced that they were in favor of not stopping Turkey's membership negotiations with the European Union.[51]

- In December 2017, then-Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz announced that they were in favor of stopping Turkey's accession negotiations with the European Union.[52]

- The European Commission's long-term budget proposal for the 2021–2027 period released in May 2018 included pre-accession funding for a Western Balkan Strategy for further enlargement, but omitted Turkey.[53]

- On 17 July 2018, then-Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, in an interview with the Greek newspaper Kathimerini, called for ending full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey and developing relations instead of full membership negotiations. Kurz said: "I have been speaking out for years about developing an honest relationship with Turkey." Kurz continued as follows: "EU membership negotiations with Turkey should be stopped immediately. Turkey has continuously moved away from Europe and its values over the last few years. We should also focus on exploring other forms of cooperation between our neighbors the EU and Turkey."[54]

- In December 2020, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that the EU has constantly applied sanctions since 1963 and that Turkey is not concerned about sanctions. He added that the EU is not honest with Turkey. These remarks came after the possibility of EU sanction due to Turkey's behavior towards Greece and Cyprus, both EU members.[55]

- In December 2020, the EU extended support to Turkey for refugees and migrants until 2022. It will give an extra €485 million to Turkey.[56]

- In August 2021, the EU sent firefighting planes to help Turkey during the 2021 Turkish wildfires.[57][58]

- In September 2023, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer, in an interview with the German newspaper Die Welt, called for the termination of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey and the development of a new concept within the relations between the EU and Turkey.[59]

- In September 2023, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced that the European Union was well into a rupture in its relations with Turkey and that they would part ways during Turkey's European Union membership process.[60]

- During the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused EU countries of "supporting attacks on Gaza while disregarding the fundamental right to life of its inhabitants."[61]

- On 18 April 2024, then-President of the European Council Charles Michel, said that they wanted to establish positive relations between the EU and Turkey and that they agreed that the EU should develop a positive and stable relationship with Turkey.[62]

- On 23 November 2024, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated that they support the International Criminal Court's arrest decision against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, and called on 27 EU member states to arrest Netanyahu and Gallant.[63]

- On 17 December 2024, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in his meeting with President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, stated that they wanted to open a new page in EU-Turkey relations, that Turkey's EU accession negotiations were a strategic goal, that the customs union should be updated again, and that visa liberalization negotiations should be resumed. He announced that they expect the EU-Turkey summit to be held as soon as possible.[64]

Contemporary issues

editEU–Turkey relations deteriorated significantly after the 2016–17 Turkish purges, including the suppression of its media freedom and the arrests of journalists, as well as the country's turn to authoritarianism under the AKP and Erdoğan.

Developing the customs union

editThe 1996 Customs Union between the EU and Turkey in the view of both sides needs an upgrade to accommodate developments since its conclusion; however, as of 2017, technical negotiations to upgrade the customs union agreement to the advantage of both sides are complicated by ongoing tension between Ankara and Brussels.[65] On 26 June 2018, reacting to the Turkish general election two days earlier, the EU's General Affairs Council stated that "the Council notes that Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union" and thus "no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen."[7][8]

EU pre-accession support to Turkey

editTurkey receives payments from the EU budget as pre-accession support,[66] currently 4.5 billion allocated for the 2014–2020 period (about 740 million Euros per year).[67] The European Parliament's resolution in November 2016 to suspend accession negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns called for the Commission to "reflect on the latest developments in Turkey" in its review of the funding program,[18][68] The ALDE faction has called for a freezing of pre-accession funding.[69] The EP's rapporteur on Turkey, Kati Piri, in April 2017 suggested the funds should be converted and concentrated to support those of the losing "No" side in the constitutional referendum, who share European values and are now under "tremendous pressure".[70]

In June 2017, the EU's financial watchdog, the European Court of Auditors, announced that it would investigate the effectiveness of the pre-accessions funds which Turkey has received since 2007 to support rule of law, civil society, fundamental rights, democracy and governance reforms.[71] Turkish media commented that "perhaps it can explain why this money apparently failed to have the slightest effect on efforts to prevent the deterioration of democracy in this country."[72]

The European Commission's long-term budget proposal for the 2021–2027 period released in May 2018 included pre-accession funding for a Western Balkan Strategy for further enlargement, but omitted Turkey.[53]

Turkey persecuting political dissenters as "terrorists"

editThe increasing persecution of political dissenters as alleged "terrorists" in Turkey[73] creates political tension between the EU and Turkey in both ways: while the EU criticises the abuse of "anti-terror" rhetoric and legislation to curb freedom of speech, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan frequently accuses the 27 EU member states and the EU of "harboring terrorists" for providing safe haven to Turkish citizens persecuted for their political views. Turkey called on the 27 EU member states and the EU to end support for the Gülen movement and the PKK, not to host them, to stop the activities of the two organizations, and to extradite the members of the two organizations to Turkey. In April 2017, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) voted to reopen its monitoring procedure against Turkey. This vote is widely understood to deal a major blow to Turkey's goal of eventual EU membership, as exiting that process was made a precondition of EU accession negotiations back in 2004.[74]

EU-Turkey deal on migrant crisis

editThe 2015 refugee crisis had a great impact on relations. They became functional, based on interdependence as well as the EU's relative retreat from political membership conditionality. The March 2016 EU-Turkey 'refugee deal' made for deeper functional cooperation with material and normative concessions made by the EU.[75]

In February 2016, Erdoğan threatened to send the millions of refugees in Turkey to EU member states,[76] saying: "We can open the doors to Greece and Bulgaria anytime and we can put the refugees on buses ... So how will you deal with refugees if you don't get a deal? Kill the refugees?"[77]

On 20 March 2016, a deal between the EU and Turkey to tackle the migrant crisis formally came into effect. The agreement was intended to limit the influx of irregular migrants entering the EU through Turkey. A central aspect of the deal is the return to the Turkish capital of Ankara any irregular migrant who is found to have entered the EU through Turkey without having already undergone a formal asylum application process. Those that had bypassed the asylum process in Turkey would be returned and placed at the end of the application line.[78]

Greece is often the first EU member-state entered by irregular migrants who have passed through Turkey. Greek islands such as Lesbos are hosting increasing numbers of irregular migrants who must now wait for the determination of asylum status before moving to their ultimate destinations elsewhere in Europe. Some 2,300 experts, including security and migration officials and translators, were set to arrive in Greece to help enforce the deal. "A plan like this cannot be put in place in only 24 hours," said government migration spokesman Giorgos Kyritsis, quoted by AFP. Additional administrative help will be necessary to process the increasing backlogs of migrants detained in Greece as a result of the EU-Turkey deal.

In exchange for Turkey's willingness to secure its borders and host irregular migrants, the EU agreed to resettle, on a 1:1 basis, Syrian migrants living in Turkey who had qualified for asylum and resettlement within the EU. The EU further incentivised Turkey to agree to the deal with a promise of lessening visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and by offering the Turkish government a payment of roughly six billion euros. Of these funds, roughly three billion euros were earmarked to support Syrian refugee communities living in Turkey.

By the end of 2017, the EU-Turkey deal had been successful in limiting irregular migration into Europe through Turkey. However, there are still many doubts about the implementation of the agreement, including how the deal may violate human rights protections outlined in the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Critics have argued that the deal is essentially a deterrence strategy that seeks to encourage irregular migrants to file their asylum applications in Turkey rather than face being apprehended and sent back to Ankara, ultimately prolonging their application process.

In December 2020, the contract finished[43] and EU extended it until 2022, giving extra €485 million to Turkey.[56]

Key points from the agreement

- Turkey's EU accession negotiations: Both sides agreed to "re-energise" Turkey's bid to join the European bloc, with talks due by July 2016.

- Additional financial aid: The EU is to speed up the allocation of €3bn ($3.3 bn; £2.3 bn) in aid to Turkey to help Syrian migrant communities

- Visa liberalisation process: Turkish nationals should have access to the Schengen passport-free zone by June 2016, provided that Turkey by then fulfills the known conditions for the step (see section below). This will not apply to non-Schengen countries like Britain.

- One-for-one: For each Syrian returned to Turkey, a Syrian migrant will be resettled in the EU. Priority will be given to those who have not tried to illegally enter the EU and the number is capped at 72,000.

- Returns: All "irregular migrants" crossing from Turkey into Greece from 20 March will be sent back. Each arrival will be individually assessed by the Greek authorities.[79]

- Emergency Relocation: Refugees waiting for asylum in Greece and Italy will be relocated to Turkey first, to reduce the strain on these states and improve living conditions for those seeking asylum.[80]

Criticism

Critics have said the deal could force migrants determined to reach Europe to start using other and potentially more dangerous routes, such as the journey between North Africa and Italy. Human rights groups have strongly criticised the deal, with Amnesty International accusing the EU of turning "its back on a global refugee crisis".[81] A Chatham House paper argued that the deal, by excessively accommodating Erdoğan's demands, is encouraging Turkey to extract "more unilateral concessions in the future."[82][83] One of the main issues many human rights organszations have with the deal is Turkey fails to meet the standards for hosting refugees. Specifically, many refugees are unable to apply for asylum while in Turkey and while there, they have low-quality living standards.[84] Moreover, in Turkey, refugees are limited to specific areas, which are often lacking in critical infrastructure such as hospitals.[80]

Effectiveness

As of 2019, the deal has had mixed success. It has drastically cut the number of migrants entering European countries, dropping by over half within three years. This result is the most pronounced in European countries situated farther west.[85] However, the portion of the deal that dictated asylum seekers who landed in Greece would be returned to Turkey has been difficult to implement. A small percentage of these people were returned, amounting to 2,130 people. The risk of violating both European and international law has made this key portion of the deal far less successful than it was intended to be.[86]

Turkey's dispute with Cyprus and Greece

editThere is a long-standing dispute over Turkey's maritime boundaries with Greece and Cyprus and drilling rights in the eastern Mediterranean.[87] Turkey does not recognise a legal continental shelf and exclusive economic zones around the Greek islands and Cyprus.[88] Turkey is the only member state of the United Nations that does not recognise Cyprus, and is one of the few not signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which Cyprus has signed and ratified.

In October 2022, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades condemned the European Union's "double standards" and "tolerance" toward Turkey under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, arguing that "Interests cannot take precedence over principles and values. We cannot say that we are currently making sacrifices to help Ukraine – and rightly so – to cope with the illegal invasion and violation of its territorial integrity and, at the same time, we put our interests first in our relations with Turkey."[89]

In August 2023, Turkish-Cypriot security forces (police and military) attacked U.N. peacekeepers inside the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus at the Pyla. The clashes started over unauthorised construction work in an area under U.N. control. Three peacekeepers were seriously injured and required hospitalisation and U.N. property has been damaged.[90] The U.N. Security Council condemned the incident and the U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said that "threats to the safety of U.N. peacekeepers and damage to U.N. property are unacceptable and may constitute serious crimes under international law."[91] The European Union also condemned it, but the Turkish president accused the UN force of bias against Turkish Cypriots and added that Turkey will not allow any "unlawful" behavior toward Turks on Cyprus.[92]

Visa liberalisation process

editThe EU Commissioner of Interior Affairs Cecilia Malmström indicated on 29 September 2011 that the visa requirement for Turkish citizens will eventually be discontinued.[93] Visa liberalisation will be ushered in several phases. Initial changes were expected in the autumn of 2011, which would include the reduction of visa paperwork, more multi-entry visas, and extended stay periods. In June 2012, the EU authorised the beginning of negotiations with Turkey on visa exemptions for its citizens. Turkish EU Minister Egemen Bağış stated that he expected the process to take 3–4 years.[94] The current visa policy of the EU is a cause of much concern for Turkish businessmen, politicians and Turks with family members in the EU. Egemen Bağış described the situation as: "Even non-candidate countries such as Russia, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia are currently negotiating for visa-free travel."[95][96][97][98][99][100] In September 2012, Turkish Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan, during a meeting at the WKÖ, said: "We have had a Customs Union for 17 years, and half of our (Turkey's) external trade is with Europe. Our goods can move freely, but a visa is required for the owner of the goods. This is a violation of human rights."[95]

In December 2013, after signing a readmission agreement, the EU launched a visa liberalisation dialogue with Turkey including a "Roadmap towards the visa-free regime".[101] After the November 2015 2015 G20 Antalya summit held in Antalya, Turkey, there was a new push forward in Turkey's EU accession negotiations, including a goal of lifting the visa requirement for Turkish citizens.[102] The EU welcomed the Turkey's commitment to accelerate the fulfilment of the Visa Roadmap benchmarks set forth by participating EU member states.[103] A joint action plan was drafted with the European Commission which developed a roadmap with certain benchmarks for the elimination of the visa requirement.[104] The agreement called for abolishing visas for Turkish citizens within a year if certain conditions are satisfied.[105]

On 18 March 2016, EU reached a migration agreement with Turkey, aiming at discouraging refugees from entering the EU. Under this deal, Turkey agreed to take back migrants who enter Greece and send legal refugees to EU. In exchange, EU agreed to give Turkey six billion euros, and to allow visa-free travel for Turkish citizens by the end of June 2016 if Turkey meets 72 conditions.[106] In March 2016, the EU assessed that Turkey at the time met 35 of the necessary 72 requirements for visa-free travel throughout Europe.[107] In May 2016, this number had risen to 65 out of 72.[108]

On 19 April 2016, Jean-Claude Juncker said that Turkey must meet the remaining criteria to win visa-free access to the Schengen area. But Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu argued that Turkey would not support the EU-Turkey deal if EU did not weaken the visa conditions by June 2016.[109] In May 2016, the European Commission said that Turkey had met most of the 72 criteria needed for a visa waiver, and it invited EU legislative institutions of the bloc to endorse the move for visa-free travel by Turkish citizens within the Schengen Area by 30 June 2016.[110] The European Parliament would have to approve the visa waiver for it to enter into force and Turkey must fulfil the final five criteria.[111] The five remaining benchmarks still to be met by Turkey include:

- Turkey must pass measures to prevent corruption, in line with EU recommendations.

- Turkey must align national legislation on personal data protection with EU standards.

- Turkey needs to conclude an agreement with Europol.

- Turkey needs to work with all EU members on criminal matters.

- Turkey must bring its terror laws in line with European standards.[112]

As of August 26, 2021, these conditions had yet to be fulfilled.[113] On 25 June 2021, the EU approved plans to pay Turkey a further three billion euros to update this agreement.[114] In August 2021, however, with President Erdoğan's Justice and Development party polling at historic lows, and with the withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan triggering fears of a new wave of migration to Europe through Turkey, Erdoğan cast doubt on the viability of this arrangement.[113]

2017 Dutch–Turkish diplomatic crisis

editOn March 11, 2017, there was a diplomatic crisis between the EU member Netherlands and Turkey. EU member Netherlands did not allow two Turkish ministers to enter its country. For example, the EU member Netherlands canceled the flight permit of Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, then did not allow Fatma Betül Sayan Kaya, the former Turkish Minister of Family and Social Policies, to enter her country, and expelled her.[115][116] The EU announced that it promised support and solidarity to the Netherlands, but did not promise support and solidarity to Turkey.[117]

2018 Turkish military intervention in Syria

editOn 22 January 2018, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini said she was "extremely worried" and would seek talks with Turkish officials. She expressed her concerns for two reasons: "One side is the humanitarian one – we need to make sure that humanitarian access is guaranteed and that civilian population and people are not suffering from military activities on the ground." The second issue was the offensive "can undermine seriously the resumption of talks in Geneva, which is what we believe could really bring sustainable peace and security for Syria".[118] On 8 February 2018, the European Parliament condemned the mass arrest of critics in Turkey of the Afrin operation, and criticized the military intervention as raising serious humanitarian concerns. "[MEPs] are seriously concerned about the humanitarian consequences of the Turkish assault and warn against continuing with these disproportionate actions," the parliament's statement said.[119] On 19 March 2018, Federica Mogherini criticized Turkey, saying that international efforts in Syria are supposed to be "aiming at de-escalating the military activities and not escalating them."[120]

2018 EU–Turkey summit

editOn March 26, 2018, the European Union–Turkey Summit was held in Varna, Bulgaria. The EU term chairman, former Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov, former EU Council President Donald Tusk, former EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan also attended the summit.[121][122]

2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria

editHigh Representative Federica Mogherini issued a declaration on behalf of the EU on 9 October 2019 stating that "In light of the Turkish military operation in north-east Syria, the EU reaffirms that a sustainable solution to the Syrian conflict cannot be achieved militarily."[123] On 14 October 2019, following Turkey's offensive the Council of the European Union released a press statement condemning Turkey's military action and called for Turkey to cease its "unilateral" military action in north-eastern Syria. It again recalled previous made statements by member states to halt arms exports licensing to Turkey and also recalled that it would not provide "stabilisation or development assistance where the rights of local populations are ignored or violated."[124][125] Finland and Sweden, the two European Union members that want to become NATO members, stopped arms sales to Turkey due to Turkey's military operation in Syria.[126][127] EU member Sweden lifted the arms embargo it imposed on Turkey in September 2022,[128] and another EU member Finland lifted the arms embargo on Turkey in January 2023.[129]

Turkish espionage

editIn 2016, Bundestag Parliamentary Oversight Panel members demanded an answer from the German government regarding the reports that Germans of Turkish origin are being pressured in Germany by informers and officers of Turkey's MIT spy agency. According to reports Turkey had 6,000 informants plus MIT officers in Germany who were putting pressure on "German Turks". Hans-Christian Ströbele stated that there was an "unbelievable" level of "secret activities" in Germany by Turkey's MIT agency. According to Erich Schmidt-Eenboom, not even the former communist East German Stasi secret police had managed to run such a large "army of agents" in the former West Germany: "Here, it's not just about intelligence gathering, but increasingly about intelligence service repression."[130]

In 2017, the Flemish interior minister, Liesbeth Homans, started the process of withdrawing recognition of the Turkish-sponsored and second largest mosque in the country, Fatih mosque in Beringen, accusing the mosque of spying in favor of Turkey.[131][132]

In 2017, Austrian politician Peter Pilz released a report on the activities of Turkish agents operating through ATIB (Avusturya Türkiye İslam Birliği – Austria Turkey Islamic Foundation), the Diyanet's arm responsible for administering religious affairs across 63 mosques in the country, and other Turkish organisations. Pilz's website faced a DDoS attack by Turkish hacktivists and heavy security was provided when he presented the report publicly. Per the report, Turkey operates a clandestine network of 200 informants targeting opposition as well as Gülen supporters inside Austria.[133]

Murders of Kurdish activists

editIn 1994, Mehmet Kaygisiz, a Kurdish man with links to the PKK (which is designated as a terrorist organisation by Turkey and the EU), was shot dead at a café in Islington, London. His murder remained unsolved and at the time his murder was thought to be drug-related, but in 2016 new documents suggest that Turkey's National Intelligence Organization (MIT) ordered his murder.[135]

Turkey's MIT was blamed for the 2013 murders of three Kurdish activists in Paris.[135]

United Nations arms embargo to Libya

editThe European Union launched Operation Irini with the primary task of enforcing the United Nations arms embargo to Libya because of the Second Libyan Civil War. During this period there were several incidents between the Irini forces and the Turkish forces.

Armenia–Turkey normalization process

editOn 14 January 2022, the European Union welcomed the normalization of Armenia–Turkey relations.[136]

Turkey's opposition to NATO membership of two EU member states

editIn May 2022, Turkey opposed two EU member states, Finland and Sweden, joining NATO because according to Turkey, they host terrorist organisations which act against Turkey (including the PKK, KCK, PYD, YPG and Gulen movement).[137] Turkey urged the countries to lift their arms embargo on Turkey, not to support the organizations, and to extradite members of the Gülen movement and PKK from the two member states. In May 2022, Turkey requested the extradition of members of the Gülen movement and PKK from the two EU member states, but this was rejected. In May 2022, Turkey quickly blocked two EU members Finland and Sweden from starting their NATO membership applications. On 18 May 2022, Turkey asked the two member states to end their support for PKK, PYD, YPG and the Gülen movement and to stop their activities. On 28 June 2022, Turkey signed the tripartite memorandum with Finland and Sweden at the Madrid summit in Madrid, Spain. Turkey called on two EU members, Finland and Sweden, to fulfill their commitments in the tripartite memorandum. Turkey asked the two member states to end the Kurdish demonstrations. Turkey asked the two member countries to end what it said was Islamophobia and to stop the burning of the Quran. However, the Gülen movement is not on the EU's list of terrorist organizations, while the PKK is on the EU's list of terrorist organizations.[138][139][140][141][142] [143] While Finland was given NATO approval by Turkey in March 2023, the Turkish parliament did not accept Sweden's application to join NATO until 23 January 2024.

2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake

editThe European Union expressed its condolences to those who lost their lives due to the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, and wished the injured a speedy recovery. The EU has announced that they are ready to help Turkey and Syria.[144]

Comparison

edit| European Union | Turkey | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 447,206,135[145] | 84,680,273 |

| Area | 4,324,782 km2 (1,669,808 sq mi)[146] | 783,356 km2 (302,455 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 115/km2 (300/sq mi) | 110/km2 (284.9/sq mi) |

| Capital | Brussels (de facto) | Ankara |

| Government | Supranational parliamentary democracy based on the European treaties[147] | Unitary presidential |

| First Leader | High Authority President Jean Monnet | President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk |

| Current Leader | Council President António Costa Commission President Ursula von der Leyen |

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan Vice President Cevdet Yılmaz |

| Official languages | 24 official languages, of which 3 considered "procedural" (English, French and German)[148] | Turkish |

| Main Religions | 72% Christianity (48% Roman Catholicism, 12% Protestantism, 8% Eastern Orthodoxy, 4% Other Christianity), 23% non-Religious, 3% Other, 2% Islam |

92% Islam, 6% Irreligion, 2% Other, 0.2% Christianity |

| Ethnic groups | Germans (ca. 80 million), French (ca. 67 million), Italians (ca. 60 million), Spanish (ca. 47 million), Poles (ca. 46 million), Romanians (ca. 16 million), Dutch (ca. 16 million), Greeks (ca. 11 million), Portuguese (ca. 11 million), and others |

70-75% Turkish, 19% Kurds, 6-11% others or not stated |

| GDP (nominal) | $16.477 trillion, $31,801 per capita | $942 billion, $10,863 per capita |

Summits

editEU-Turkey Summits

edit- 1st EU-Turkey Summit: 26 March 2018 in Varna, Bulgaria

- 2nd EU-Turkey Summit: No date or place yet announced

Turkey's foreign relations with EU member states

editTurkey has no diplomatic relations with Cyprus as Turkey does not recognize the government of the Republic of Cyprus.

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Fifty Years On, Turkey Still Pines to Become European". TIME. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "Turkey's bid to join the EU is a bad joke; but don't kill it". The Economist. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ^ But in the other hand Turkey was always being asked to join eu by other countries "Turkey is no longer an EU candidate", MEP says Archived 2020-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, Euronews

- ^ a b "Turkey's EU dream is over, for now, top EU official says". Hürriyet Daily News. 2 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Erdogan warns Europeans 'will not walk safely' if attitude persists, as row carries on". Reuters. 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ a b "New clashes likely between Turkey, Europe". Al-Monitor. 23 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "EU Council issues strong message about Turkey's obligations". Cyprus Mail. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "EU will Zollunion mit der Türkei nicht ausbauen". Die Zeit (in German). 27 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Turkey and EU". Embassy of the Republic of Turkey (Washington, DC). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ "Turkey and the Council of Europe". Council of Europe. 27 October 2006. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- ^ "Greece and Turkey accede to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization". NATO Media Library. NATO. 18 February 1952. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- ^ Ahıska, Meltem (2003) “Occidentalism: The Historical Fantasy of the Modern” South Atlantic Quarterly 102/2-3, Spring-Summer 2003 (Special Issue on Turkey: “Relocating the Fault Lines. Turkey Beyond the East-West Divide”), pp. 351–379.

- ^ Taspinar, Omer (September 2008). "Turkey's Middle East Policies: Between Neo-Ottomanism and Kemalism". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ Murinson, Alexander (2009). Turkey's Entente with Israel and Azerbaijan: State Identity and Security in the Middle East and Caucasus (Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Politics). Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-415-77892-3.

- ^ Kubilay Yado Arin: The AKP's Foreign Policy, Turkey's Reorientation from the West to the East? Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2013. ISBN 9 783865 737199.

- ^ Robin Emmott, Alastair Macdonald (2016-07-18). "EU condemns Turkey coup bid, warns Erdogan on death penalty". Reuters.

- ^ "Turkey in no position to become EU member any time soon: Juncker". Reuters. July 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Freeze EU accession talks with Turkey until it halts repression, urge MEPs". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ^ "EU parliament votes overwhelmingly in favour of scrapping Turkey accession talks". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2016-12-08.

- ^ "EU says won't expand Turkey membership talks". Yahoo. 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Marc Pierini (12 December 2016). "Turkey's Impending Estrangement From the West". Carnegie Europe. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ "Turkey scolds Austria in EU membership dispute". bbc.com. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "Austrian Chancellor Kurz urges to stop Turkey's EU accession talks". armenpress.am. 26 March 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ "AP: Türkiye ile müzakereler askıya alınsın". DW Türkçe (in Turkish). July 6, 2017.

- ^ "ENLARGEMENT AND STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION PROCESS Council conclusions" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 26 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "European Parliament calls for suspension of Turkey EU accession talks". Euronews. March 13, 2019.

- ^ a b "EU-Turkey relations are at a historic low point, say MEPs". European Parliament. May 19, 2021.

- ^ Huseyin Hayatsever, Ece Toksabay (2023-07-10). "Erdogan links Sweden's NATO membership to Turkey's EU accession". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ "AP raporu: Türkiye'nin AB üyelik süreci mevcut koşullarda devam edemez" (in Turkish). Gazete Duvar. 2023-07-18.

- ^ "DN/Ipsos: Väljarna vill inte ha Turkiet i EU" (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. 2023-09-04.

- ^ "Council Conclusions on Enlargement and Stabilisation and Association Process" (PDF). consilium.europa.eu. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-22. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ "Does 'Islamic Democracy' Exist? Part 4: Turkey's Great Leap Forward". Spiegel Online. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "America's Dark View of Turkish Premier Erdogan". Der Spiegel. 30 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Turkey's Vote Makes Erdoğan Effectively a Dictator". The New Yorker. 17 April 2017. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Pour ou contre l'adhésion de la Turquie à l'Union européenne". lemonde.fr (in French). November 8, 2002.

- ^ Kubosova, Lucia (January 15, 2007). "Sarkozy launches presidential bid with anti-Turkey stance". EUobserver. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Barroso says Turkey not ready for EU membership, urges continued negotiations". Zaman, Javno.hr, DPA, Reuters. Southeast European Times. 22 July 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "Van Rompuy urges EU for closer partnership with Turkey". Today's Zaman. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Die Welt: Vor Treffen mit Gül: Merkel lehnt EU-Mitgliedschaft der Türkei ab Archived 2020-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, 20 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011

- ^ "Turkey's EU process an end in itself, says Turkish diplomat – POLITICS". 7 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Sarmadi, Dario (21 May 2014). "Juncker and Schulz say 'no' to Turkey in last TV duel". euractiv.com. Efficacité et Transparence des Acteurs Européens. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ My Foreign Policy Objectives Archived 2020-08-18 at the Wayback Machine, Official website of EU President Juncker, "When it comes to enlargement, this has been a historic success. However, Europe now needs to digest the addition of 13 Member States in the past 10 years. Our citizens need a pause from enlargement so we can consolidate what has been achieved among the 28. This is why, under my Presidency of the Commission, ongoing negotiations will of course continue, and notably the Western Balkans will need to keep a European perspective, but no further enlargement will take place over the next five years. As regards Turkey, the country is clearly far away from EU membership. A government that blocks twitter is certainly not ready for accession."

- ^ a b "EU finishes contracting $7.3 bln refugee deal with Turkey". hurriyetdailynews. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "President Erdogan says freedom and democracy have 'no value' in Turkey amid arrests and military crackdown". The Independent. 18 March 2016. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Cameron: Turkey on course to join EU 'in year 3000'". Business Reporter. 23 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "EU: Turkey can't join if it introduces death penalty". cnn.com. July 18, 2016.

- ^ "Austrian chancellor wants EU to end accession talks with Turkey". euractiv.com. August 4, 2016.

- ^ "Erdogan accuses EU of 'crusade' against Islam". Deutsche Welle. 17 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Deutsche Politiker geben Zurückhaltung gegenüber Erdogan auf". Die Welt. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "In shift, Merkel backs end to EU-Turkey membership talks". Reuters. 3 September 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ "Finlandiya'dan Türkiye'ye AB desteği". ntv.com.tr (in Turkish). September 7, 2017.

- ^ "Austrian PM Kurz calls to end EU-Turkey membership talks". dailysabah.com. December 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "EU plans to cut financial assistance to Turkey". Ahval. 6 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "Kurz: EU must stop Turkey accession talks 'immediately'". ekathimerini.com. July 17, 2018.

- ^ "EU never treated Turkey fairly since 1963: Erdoğan". hurriyetdailynews. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ a b "EU extends support for refugees in Turkey to early 2022". 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-12-24. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ^ "EU sends firefighting planes for Turkey wildfires". 2 August 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-08-02. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Recep Tayyip Erdoğan [@RTErdogan] (3 August 2021). "Thank You" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Österreich für Ende der EU-Beitrittsgespräche mit der Türkei". welt.de (in German). September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Turkey could part ways with EU if necessary, Erdogan says". Reuters. 16 September 2023.

- ^ "Erdoğan slams EU response to Gaza war". hurriyetdailynews. 26 October 2023. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023.

- ^ "AB Konseyi Başkanı Michel'den AB zirvesi sonrası Türkiye açıklaması" (in Turkish). NTV. 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan'dan UCM'nin Netanyahu kararı hakkında açıklama" (in Turkish). Haber7. 23 November 2024.

- ^ "President Erdogan calls for stronger and institutionalised ties with EU". TRT World. 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Turkey-EU tension endangers upgrade to customs union". Hurriyet Daily News. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "Erdogan's Achilles' Heel". Handelsblatt. 4 April 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkey - financial assistance under IPA II". European Commission. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "P8_TA-PROV(2016)0450". European Parliament. 2016-11-24. Archived from the original on 2017-11-12. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ "MEPs urge freezing Turkey membership talks". Euraktiv. 2016-11-23. Archived from the original on 2017-05-02. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ^ "Top Turkey MEP urges talks with Erdogan on accession". EU Observer. 19 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Turkey received €1bn in EU money to develop democracy". EU Observer. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Where did all the money from the EU to Turkey go?". Hurriyet Daily News. 4 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Zia Weise (24 March 2016). "In Erdogan's Turkey, Everyone Is a Terrorist". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Turkey's EU bid in jeopardy after Council of Europe vote". Euractiv. 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Beken Saatçioğlu, "The European Union's refugee crisis and rising functionalism in EU-Turkey relations." Turkish Studies 21.2 (2020): 169-187.

- ^ "Erdogan to EU: 'We're not idiots', threatens to send refugees". EUobserver. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkey's Erdogan threatened to flood Europe with migrants: Greek website". Reuters. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "EU-Turkey migrant deal: A Herculean task". BBC News. 2016-03-18. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ Gkliati, Mariana (2017). "The EU-Turkey Deal and the Safe Third Country Concept before the Greek Asylum Appeals Committees" (PDF). Movements, Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies. 3 (2): 213–224. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ a b "EU-Turkey deal two years after: the burden on refugees in Greece ⁄ Open Migration". Open Migration. 2018-04-11. Archived from the original on 2019-11-10. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "EU-Turkey refugee deal a historic blow to rights". Amnesty International. 18 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "The EU-Turkey refugee deal solves little". Chatham House. 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "A year of loneliness on Greek Islands: The EU-Turkey refugee agreement". 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ^ "The EU-Turkey deal: Europe's year of shame". www.amnesty.org. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2019-11-10. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "3 years on, what's become of the EU-Turkey migration deal?". AP NEWS. 2019-03-20. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Two years into the EU-Turkey 'deal' – taking stock". Jacques Delors Institut - Berlin. 2018-03-15. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Cyprus: EU 'appeasement' of Turkey in exploration row will go nowhere". Reuters. 17 August 2020. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Turkey threatens Greece over disputed Mediterranean territorial claims". Deutsche Welle. 5 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "The EU's 'tolerance' and 'double standards' with Turkey embolden Erdoğan, claims Cyprus President". Euronews. 11 October 2022.

- ^ "UN peacekeepers hurt in Cyprus buffer zone clash with Turkish forces". reuters. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023.

- ^ "U.N. calls unauthorized construction by Turkish Cypriots a violation of the status quo on Cyprus". Archived from the original on 22 August 2023.

- ^ "Erdoğan slams UN peacekeepers for blocking road project in Turkish Cyprus". Archived from the original on 22 August 2023.

- ^ EU prepares road map to remove visa for Turks Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review (29 September 2011)

- ^ "Visa exemption in 3–4 years, says EU minister". Anatolia News Agency. 22 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Çağlayan'dan vize uygulamasına tepki: 'AB insanlık suçu işliyor'". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Dış Politika Enstitüsü". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Being fair to Turkey is in the EU's interest". 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "'EU visa policy on Turkey is illegal,' German-based advocacy group says". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Güsten, Susanne (28 June 2012). "Turks Seek Freedom to Travel to Europe Without Visas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Bagis, Egemen (14 July 2012). "Visa restrictions are shutting Turkey out of the EU". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "Cecilia Malmström signs the Readmission Agreement and launches the Visa Liberalisation Dialogue with Turkey". European Commission. 6 November 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Pence, Anne; Utku, Sinan (16 November 2015). "Hosting G20 Leaders is Opportunity for Turkey on Growth and Stability". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "European Commission - Statement Meeting of heads of state or government with Turkey - EU-Turkey statement, 29/11/2015". Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ De Ruyt, Jean (2 December 2015). "The EU – Turkey summit of 29 November 2015 : A "Re-Energised" Relationship". The National Law Review. Covington & Burling LLP. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Declaring 'new beginning,' EU and Turkey seal migrant deal". Reuters. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ E.U. strikes deal to return new migrants to Turkey Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine A. Faiola and G. Witte, The Washington Post, 18 March 2016

- ^ Timmermans: 'De EU laat zich niet chanteren door Turkije' (Dutch) Archived 2016-08-29 at the Wayback Machine, de Volkskrant

- ^ "Erdogan haalt uit naar EU over aanpassing terreurwetten". 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ European Commission's Jean-Claude Juncker Says Criteria For Turkey's Visa Waiver Will Not Be 'Watered Down' Archived 2016-05-31 at the Wayback Machine S. Shankar, International Business Times, 19 April 2016

- ^ "European Commission opens way for decision by June on visa-free travel for citizens of Turkey". European Commission. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "EU commission backs Turkish citizens' visa-free travel". Aljazeera. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "EU backs Turkey visa deal, but says conditions must be met". BBC News. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ a b Yackley, Ayla Jean (26 August 2021). "Turkey will not act as EU 'warehouse' for Afghan refugees, says Erdogan". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2021-09-05. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ "EU greenlights major funding plan for refugees in Turkey". AP NEWS. 2021-06-25. Archived from the original on 2021-09-05. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ^ "Hollanda, Dışişleri Bakanı Çavuşoğlu'nun uçuş iznini iptal etti!". BirGün (in Turkish). March 11, 2017. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ "Hollanda polisi Bakan Kaya'nın yolunu kapattı". ensonhaber.com (in Turkish). March 11, 2017. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Donald Tusk and Jean Claude Juncker condemn Turkey's remarks". armenpress.am. March 15, 2017.

- ^ i24NEWS. "EU's Mogherini 'extremely worried' by ongoing Turkish offensive in Syria". i24NEWS. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "European Parliament condemns Turkey's crackdown on Afrin critics". Deutsche Welle. 8 February 2018.

- ^ "EU criticizes Turkey's offensive in Syrian town of Afrin". Chicago Tribune. 19 March 2018.

- ^ "EU-Turkey leaders' meeting in Varna (Bulgaria), 26 March 2018". consilium.europa.eu. March 26, 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan, Türkiye-AB Zirvesi nedeniyle Bulgaristan'a gitti". tccb.gov.tr (in Turkish). March 26, 2018. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on recent developments in north-east Syria". 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "North East Syria: Council adopts conclusions". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Foreign Affairs Council, 14 October 2019". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Finlandiya, Türkiye'ye silah satışını durdurdu". ANF (in Turkish). October 9, 2019. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ "İsveç, Türkiye'ye silah satışını durdurdu". ANF (in Turkish). October 16, 2019. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ "Sweden resumes arms exports to Turkey after NATO membership bid". National Post. 2022-09-30. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ "Finland permits first defence export to Turkey since 2019". Middle East Eye. 2023-01-25. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ "Report: Turkey's MIT agency menacing 'German Turks'". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Gotev, Georgi (April 7, 2017). "Flemish minister: Turkish-sponsored mosque is 'nest of spies'". Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Solmaz, Mehmet (July 6, 2017). "Influenced by Gülenists, Belgium targets Turkish mosques fighting extremism". Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Turkey's Influence Network In Europe Is Leading To Tension". huffingtonpost. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Suspect in murders of Kurdish activists dies in Paris hospital". France 24. 17 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ a b "New documents appear to link Turkish state with murder in London". The Independent. 27 September 2016. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Turkey/Armenia: Statement by the Spokesperson on the normalisation process". eeas.europa.eu. January 14, 2022. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ "Erdogan says Turkey not supportive of Finland, Sweden joining NATO". reuters. 13 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ "Turkey says Sweden, Finland reject extradition requests for PKK, Gulen-linked suspects". Xinhua. 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye'den Finlandiya ve İsveç'e 10 maddelik manifesto". www.haber7.com (in Turkish). May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye, İsveç ve Finlandiya'ya teröristlerin iadesi için yazı gönderdi". ensonhaber.com (in Turkish). July 6, 2022. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye'den İsveç ve Finlandiya'ya NATO üyeliği için 10 şart". tgrthaber.com.tr (in Turkish). June 8, 2022. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "İsveç ve Finlandiya'ya 10 şart". www.yenisafak.com (in Turkish). June 8, 2022. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ "Turkey parliament backs Sweden's Nato membership". BBC News. 2024-01-23. Archived from the original on 23 January 2024. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Earthquake: EU support for Türkiye and Syria". consilium.europa.eu. February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Population on 1 January". Eurostat. European Commission. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Field Listing – Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - Frequently asked questions on languages in Europe". europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2017-06-24.