Dwight is a village located mainly in Livingston County, Illinois, with a small portion in Grundy County. The population was 4,032 at the 2020 census. Dwight contains an original stretch of U.S. Route 66, and from 1892 until 2016 continuously used a railroad station designed in 1891 by Henry Ives Cobb.[4] Interstate 55 bypasses the village to the north and west.

Dwight, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Buildings in downtown Dwight | |

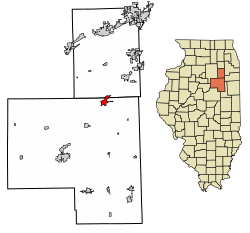

Location in Livingston and Grundy counties, Illinois | |

Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°05′54″N 88°25′29″W / 41.09833°N 88.42472°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Counties | Livingston, Grundy |

| Townships | Dwight, Goodfarm |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Paul Johnson[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.31 sq mi (8.56 km2) |

| • Land | 3.30 sq mi (8.54 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation | 633 ft (193 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 4,032 |

| • Density | 1,222.93/sq mi (472.17/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 60420 |

| Area code | 815 |

| FIPS code | 17-21358 |

| GNIS ID | 2398764[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Dwight, Illinois |

| Website | www |

Geography

editDwight is located in northeastern Livingston County. It extends north into southern Grundy County to include the commercial area near the northern exit with Interstate 55. I-55 leads northeast 77 miles (124 km) to Chicago and southwest 58 miles (93 km) to Bloomington. Illinois Route 17 passes through the center of Dwight as Mazon Avenue, leading east 30 miles (48 km) to Kankakee and west 34 miles (55 km) to Wenona. Illinois Route 47 (Union Street) passes through the east side of Dwight, leading north 18 miles (29 km) to Morris and south 44 miles (71 km) to Gibson City.

According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Dwight has a total area of 3.31 square miles (8.57 km2), of which 3.30 square miles (8.55 km2) (or 99.70%) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) (or 0.30%) is water.[5]

Climate

edit| Climate data for Dwight, Illinois, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1990–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

72 (22) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.4 (11.9) |

56.5 (13.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

80.8 (27.1) |

88.7 (31.5) |

93.0 (33.9) |

92.7 (33.7) |

91.8 (33.2) |

90.3 (32.4) |

82.7 (28.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

56.7 (13.7) |

95.1 (35.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

35.0 (1.7) |

47.5 (8.6) |

60.8 (16.0) |

72.1 (22.3) |

81.1 (27.3) |

83.5 (28.6) |

81.9 (27.7) |

77.1 (25.1) |

64.1 (17.8) |

48.5 (9.2) |

36.1 (2.3) |

59.9 (15.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

37.1 (2.8) |

48.8 (9.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

70.1 (21.2) |

72.8 (22.7) |

70.7 (21.5) |

64.2 (17.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

39.0 (3.9) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.0 (−10.0) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

36.9 (2.7) |

49.3 (9.6) |

59.1 (15.1) |

62.1 (16.7) |

59.4 (15.2) |

51.3 (10.7) |

40.2 (4.6) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

38.8 (3.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7.0 (−21.7) |

−1.9 (−18.8) |

9.4 (−12.6) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

35.1 (1.7) |

45.6 (7.6) |

51.3 (10.7) |

49.0 (9.4) |

37.8 (3.2) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

0.6 (−17.4) |

−10.8 (−23.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−19 (−28) |

−5 (−21) |

14 (−10) |

24 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

43 (6) |

41 (5) |

27 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

4 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.96 (50) |

1.64 (42) |

2.55 (65) |

3.54 (90) |

4.85 (123) |

4.60 (117) |

3.90 (99) |

3.68 (93) |

3.25 (83) |

3.19 (81) |

2.58 (66) |

1.95 (50) |

37.69 (959) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.9 (20) |

4.9 (12) |

3.5 (8.9) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

5.6 (14) |

23.3 (58.4) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 4.3 (11) |

4.0 (10) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

3.4 (8.6) |

7.7 (20) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.5 | 6.2 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 98.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 9.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[7] | |||||||||||||

History

editFounding

editDwight was laid out on January 30, 1854, by Richard Price Morgan Jr. (1828-1910), James C. Spencer (1828 – after 1890), and John Lathrop (1809 – 1870). Each of these three men took a quarter of the land. All were working as engineers for the Chicago and Mississippi Railroad. The final quarter was jointly owned by two Bloomington brothers, Jesse W. Fell (1808 – 1878) and Kersey H. Fell (1815 – 1893). All five men had links to the railroad which was to open from Bloomington to Joliet in 1854.[8]

Spencer was born in the Hudson River valley south of Albany; his ancestors included a United States Supreme Court Chief Justice and two governors of New York State; he was later to have an important career in Wisconsin railroads.[9] Lathrop was a civil engineer with a long history of working with canals and railroads in New York; he would soon return to Buffalo.[10] Morgan was the son of a noted civil engineer, and he later became nationally known for his work on electric railroads in New York. The Fell brothers were Bloomington land developers who had been active in helping found many central Illinois towns including Clinton, Normal, Pontiac, and Towanda. They were employed by the railroad as land agents; the Fells had a role in persuading Abraham Lincoln to write his autobiography.[11]

The plan of the founders was to purchase a block of land along the route of the railroad, and to divide it into four equal parts. Morgan would then take charge of the operation. He would draw up a plan of the new town, sell the lots, and divide the proceeds among the others. The station was to be placed at the point where the four quarters met. Any unsold lots would be divided among the partners. The other men seemed to believe that Morgan was acting in the interest of the railroad.[12] The town was named for Henry Dwight, who had funded most of the construction of this part of the railroad.[13] The Chicago and Mississippi soon became the Chicago and Alton Railroad. Attempts in 1858 to rename the settlement "Jersey", "Beckman", or "Dogtown" failed.[14]

Early Dwight

editWhen the surveyors, working for the railroad's chief engineer, Oliver H. Lee, reached the proposed location of the town in 1853, the speculators found that the tracks would pass slightly east of the planned central point and would go through lands in Morgan's area. This would have made Morgan's lots more valuable than the others. The men revised the plan so that everyone would convey their lots to Morgan, who would then sell the lots and split the total profits. This was done. In 1855 the partnership was dissolved and all unsold lots were divided among the five men.[15] To announce to the public that a town would be located here, a tin pan was placed on top of a telegraph pole.[16] Railroad workers flooded into the townsite. Morgan was afraid that they would cover lots with “Irish shanties” and make the lots unsellable. Therefore, he had John Campbell erect a boarding house.[17] This was the first building in Dwight. The first house in town was built by Augustus West in June 1854.[18] The first passenger train reached Dwight on July 4, 1854, and regular traffic on the railroad began in August of that year. The first store was a two-story building put up by David McWilliams in 1855 and painted white to attract customers. The first item sold was a pattern for a "lawn dress" that one of the workmen purchased for the wife of the station master.[19] In 1857 John Spencer began buying grain and erected a grain warehouse. A grain elevator soon followed, and a large stone mill was built in 1859.[20]

Original design of Dwight

editLike most new towns founded in Illinois in the 1850s, Dwight was designed without a town square. It was centered instead on a depot ground. This was a widened area of railroad property, about 1,000 feet (300 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) wide, where the tracks passed through the town. Such depot grounds were common in towns of the 1850s and may still be found at Gridley, Chatsworth, Odell, Towanda, McLean and many other central Illinois places. By the 1870s depot grounds had begun to fall out of favor. Morgan had deeded the central 100-foot (30 m) band to the Chicago and Mississippi, but he never turned over the remainder of the depot grounds to the railroad. This led to a lawsuit which was settled by the United States Supreme Court. The suit provides information on the early history of Dwight.[17] Dwight's original town was quite large, consisting of 24 blocks, each of which contained 28 lots. Unlike Odell, where the entire original town was aligned with the railroad, only the small central part of the original town of Dwight paralleled the tracks, with West Street running diagonally on the northwest side of the railroad and East Street on the south side. In the remainder of the original town, streets ran true north-south or east-west. This created two odd triangles of land where these streets met the diagonal streets at the center of town. The southeastern triangle became the site of Dwight’s waterworks. The early depot was on the northwest side of the tracks.[21]

Prince Albert's visit

editIn 1860 Queen Victoria's son Prince Albert, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, came to stay several days in the town, which at the time was known as Dwight's Station. The prince was traveling as Lord Renfrew, using one of his lesser titles, but this fooled no one. The visit was important enough that local people recorded the exact time the prince arrived: twenty-seven minutes after six in the afternoon on Saturday, September 22, 1860. He was to stay with James C. Spencer, one of Dwight's founders, at Spencer's farm south of town. Local couches and chairs were deemed insufficient for him, so Spencer's furniture was stored, and the prince's own furniture, which had been shipped ahead, was placed in the house.

Soon after the Crown Prince arrived he began hunting and over several days the royal party killed over 200 prairie chickens and quail. Prince Albert attended Sunday services at the local Presbyterian church. On Wednesday, September 26, he left, having planted an elm on Spencer's farm.[22] In 1878 the grounds of the house where the prince stayed were improved by the American landscape architect Ossian Cole Simonds and in the 21st century were given to the town and have become Renfrew Park.

Growth of Dwight

editIn 1869 the prospects of Dwight were improved when a second railroad line was constructed linking Dwight with Streator by the St Louis, Jacksonville and Chicago Railroad.[23] In the same year the Chicago and Alton Railroad, successor to the Chicago and Mississippi Railroad, was double-tracked from Odell to Gardner.[24]

The first brick house in Dwight was built in 1872.

In 1879 Dwight physician, Dr. Leslie Keeley, working with Richard Oughton, announced that he had found a cure for alcoholism based on gold chloride.[25] The Keeley Institute soon became world-famous treating hundreds of thousands of patients including Elliott Roosevelt, the brother of President Theodore Roosevelt.[26] Profits paid for the John R. Oughton House, on the south side of Dwight, which was constructed in 1891 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

in 1881, the Illinois, Indiana and Iowa Railroad was built east to west through the town from South Bend, Indiana, to Streator, giving it a second railroad station. This line later became part of the New York Central Railroad.[27]

By 1891 it became clear that the growing town needed a new main-line railroad station, and the C&A Railroad hired Henry Ives Cobb to design the building. The result was a splendid Richardsonian Romanesque edifice, which in 1982 was added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Dwight Railroad Station. Another new downtown building now on the National Register was the Frank L. Smith Bank, opened in 1906, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

In 1906, the Bloomington, Pontiac and Joliet Electric Railway opened to the town from Pontiac. This was intended as part of a fast electric passenger interurban service from Chicago to St. Louis, but no further construction was done.[28]

In 1921 paving was finished on the Chicago to Springfield road,[29] which in 1926 was designated as Route 66. The improvement of the road doomed the interurban railway, which shut down in 1925. In 1964 the first phase of Interstate 55 was completed, and Dwight became increasingly a highway-oriented town.

In 1930 the state of Illinois established the Oakdale Reformatory for Women, which later became the Dwight Correctional Center, west of the village.

June 2010 tornado

editOn June 5, 2010, an EF-3 tornado ripped through Streator and later Dwight. As described by one reporter who covered the disaster, the tornado "literally rearranged these towns of Dwight and Streator, with the worst damage in mobile home parks and downtown Streator. The residents of Dwight are thankful for the fact that the tornado largely spared their town."[30]

Monuments

editDwight is home to the First National Bank of Dwight, one of only three banks designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. A historic U.S. Route 66 Texaco gas station, Ambler's Texaco Gas Station, and a 1891 railway station are both listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The 1857 Dwight Pioneer Gothic Church is a rare example of a wooden Carpenter Gothic church building. John R. Oughton House is also located in Dwight.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 295 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,044 | 253.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,295 | 24.0% | |

| 1890 | 1,354 | 4.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,015 | 48.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,156 | 7.0% | |

| 1920 | 2,255 | 4.6% | |

| 1930 | 2,534 | 12.4% | |

| 1940 | 2,499 | −1.4% | |

| 1950 | 2,843 | 13.8% | |

| 1960 | 3,086 | 8.5% | |

| 1970 | 3,841 | 24.5% | |

| 1980 | 4,146 | 7.9% | |

| 1990 | 4,230 | 2.0% | |

| 2000 | 4,363 | 3.1% | |

| 2010 | 4,260 | −2.4% | |

| 2020 | 4,032 | −5.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

As of the 2020 census[32] there were 4,032 people, 1,544 households, and 1,017 families residing in the village. The population density was 1,219.23 inhabitants per square mile (470.75/km2). There were 1,863 housing units at an average density of 563.35 per square mile (217.51/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 91.15% White, 0.87% African American, 0.02% Native American, 0.69% Asian, 0.00% Pacific Islander, 1.49% from other races, and 5.78% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.49% of the population.

There were 1,544 households, out of which 27.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.53% were married couples living together, 19.62% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.13% were non-families. 31.35% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.41% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.97 and the average family size was 2.33.

The village's age distribution consisted of 22.2% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 24.6% from 45 to 64, and 19.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.2 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $56,543, and the median income for a family was $72,072. Males had a median income of $41,458 versus $31,290 for females. The per capita income for the village was $30,753. About 12.0% of families and 15.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.1% of those under age 18 and 12.9% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure

editThe Illinois Department of Corrections Dwight Correctional Center, which closed in 2013, was in Nevada Township in an unincorporated area in Livingston County, near Dwight.[33][34] The correctional center housed the State of Illinois female death row.[35]

Other sites

editDwight is also home of the first Keeley Institute and the Frank L. Smith Bank.

Dwight station, a train station designed in 1891 by Henry Ives Cobb, operated continuously from the spring of 1892 until October 2016 when a new station opened several blocks away. The original station is now the home of the Dwight Historical Society Museum and the Dwight Chamber of Commerce.[4]

The Dwight Veterans' Administration Hospital occupied the triangular-shaped block between Main Street, Mazon Avenue, and Prairie Avenue. Part of the facility was built in 1891 for the Keeley Institute.[36] In 1930 it became the Dwight V.A. Hospital, and an addition opened on May 11, 1947, with a modern surgical suite, wards, clinic, and physical therapy facilities.[37] The buildings survive and are partially occupied by the Fox Developmental Center.

Sadie planned a trip to Dwight in the "Sadie's Trip to Dwight" episode of the radio serial Vic and Sade, originally aired on June 4, 1937. The series, set in a vaguely fictionalized Bloomington, Illinois, often used towns near Bloomington in its scripts.

Notable people

edit- Hannah Tracy Cutler, abolitionist

- Tim Lee Hall, congressman from Illinois; taught in Dwight

- Clay Harbor, National Football League player and Reality TV star; raised in Dwight

- Art Mathisen, college basketball star at the University of Illinois; born in Dwight

- Diana Oughton, student activist and member of the Weather Underground; born in Dwight; died in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion in 1970

- Frank L. Smith, congressman from Illinois

- James G. Strong, congressman from Kansas; born in Dwight

- Mabel Trunnelle, early film actress; born in Dwight

- Jerry Weller, congressman from Illinois

References

edit- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Dwight, Illinois

- ^ "Welcome to Dwight, Illinois". Welcome to Dwight, Illinois. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "Dwight, IL (DWT)". The Great American Stations. AMTRAK. October 27, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

The old depot, which opened in spring 1892, will continue to house the Dwight Historical Society museum and the Dwight Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Dwight, IL". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Chicago". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ History of Livingston County, Illinois (Chicago: LeBaron, 1878) p.406.

- ^ History of Livingston, 1878, p.784.

- ^ History of the Descendants of John Dwight of Dedham, Massachusetts (New York: John F. Trow, 1874).

- ^ Frances Milton I. Morehouse, The Life of Jesse Fell (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1916).

- ^ Morgan v. Railroad Company, 96 U.S. 24L.Ed. 743, 716 (US Supreme Court 1877).

- ^ History of Livingston, 1878, p. 287.

- ^ William R. Dustin, History of Dwight from 1853–1894 (Dwight: Dustin and Wassall, 1894) p.16.

- ^ Morgan v. Railroad, 1877, p 716.

- ^ History of Livingston, 1878, p.486.

- ^ a b Morgan v. Railroad, 1877, p.716.

- ^ Dustin, 1894, p.17.

- ^ Dustin, 1894, pp. 16-18.

- ^ History of Livingston, 1878, p. 489.

- ^ Standard Atlas of Livingston County Illinois (Chicago: Ogle, 1911) p.30.

- ^ Dustin, 1894, pp. 7-8.

- ^ History of Livingston, 1878, P. 489.

- ^ History of Livingston 1878, P. 489.

- ^ Dustin, 1894, p.131

- ^ Joseph E. Persico, Franklin and Lucy: President Roosevelt Mrs. Rutherfurd and the Other Remarkable Women in His Life (New York: Random House: 2008) p. 24.

- ^ "Indiana-Illinois-Iowa Railroad". March 9, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ Hilton & Due: Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press (1963) p. 346

- ^ Blue Book of the State of Illinois 1921–1922 (Springfield: State of Illinois, 1921) p. 323.

- ^ The Dwight, Illinois Tornado of 2010

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "Dwight village, Illinois[permanent dead link]." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on September 1, 2010.

- ^ "Dwight Correctional Center." Illinois Department of Corrections. Retrieved on September 1, 2001.

- ^ "DOC Report Online Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Illinois Department of Corrections. Retrieved on September 1, 2010.

- ^ Warden, Philip (March 5, 1965). "Dwight V A Hospital Is Given to Illinois". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ Belden, David (2007). Grundy County, Postcard Historical Series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-7385-5094-7.