Dupont Circle is a historic roundabout park and neighborhood of Washington, D.C., located in Northwest D.C. The Dupont Circle neighborhood is bounded approximately by 16th Street NW to the east, 22nd Street NW to the west, M Street NW to the south, and Florida Avenue NW to the north. Much of the neighborhood is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. However, the local government Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC 2B) and the Dupont Circle Historic District have slightly different boundaries.[1]

Dupont Circle | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise from the top: Dupont Circle Fountain; Connecticut Avenue; St. Matthew's Cathedral; historic Riggs Ntl. Bank; Patterson Mansion. | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Quadrant | Northwest |

| Ward | 2 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Brooke Pinto |

Dupont Circle Historic District | |

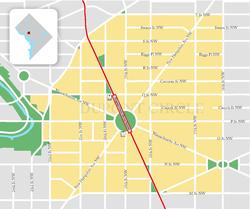

An aerial of the Dupont Circle Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Rhode Island Avenue, NW; M and N Sts., NW, on the south; Florida Avenue, NW, on the west; Swann St., NW, on the north; and the 16th Street Historic District on the east[1] |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°54′34.7″N 77°02′36.4″W / 38.909639°N 77.043444°W |

| Area | 170 acres (69 ha) |

| Architect | Mead McKim & White; Carrere & Hastings |

| Architectural style | Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Queen Anne, Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 78003056 (original) 85000238 (increase 1) 05000539 (increase 2) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 21, 1978 |

| Boundary increases | February 6, 1985 June 10, 2005 |

The traffic circle is located at the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue NW, Connecticut Avenue NW, New Hampshire Avenue NW, P Street NW, and 19th Street NW. The circle is named for Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont. The traffic circle contains the Dupont Circle Fountain in its center.

The neighborhood is known for its high concentration of embassies, many located on Embassy Row, and think tanks, many located on Think Tank Row.

History

editDupont Circle is located in the "Old City" of Washington, D.C., the area planned by architect Pierre Charles L'Enfant that remained largely undeveloped until after the American Civil War, when there was a large influx of new residents. Based on the original L'Enfant plan, the area occupied by the circle was intended to be rectangular in shape, similar to Farragut Square. Dupont Circle was once home to a brickyard and slaughterhouse.[2][3] There also was a creek, Slash Run, that began near 15th Street NW and Columbia Road NW, ran from 16th Street near Adams Morgan, through Kalorama and within a block of Dupont Circle, but the creek has since been enclosed in a sewer line.[4][5] Improvements made in the 1870s by a board of public works headed by Alexander "Boss" Shepherd transformed the area into a fashionable residential neighborhood.[6][7]

In 1871, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of the traffic circle, then called Pacific Circle, as specified in L'Enfant's plan. On February 25, 1882, Congress renamed it "Dupont Circle", and authorized a memorial statue of Samuel Francis Du Pont, in recognition of his service as a rear admiral during the Civil War.[5] Unveiled on December 20, 1884, the statue was sculpted by Launt Thompson,[5] and the circle was landscaped with exotic flowers and ornamental trees. Several prominent duPont family members deemed it too insignificant to honor their ancestor, so they secured permission to move the statue to Rockford Park in Wilmington in 1917, and commissioned Henry Bacon and Daniel Chester French to design the fountain that sits in Dupont Circle today.[8] In 1920, the current double-tiered white marble fountain replaced the statue.[9] Daniel Chester French and Henry Bacon, the co-creators of the Lincoln Memorial, designed the fountain, which features carvings of three classical figures symbolizing the sea, the stars and the wind on the fountain's shaft.[1]

In 1876, the second house located directly in Dupont Circle was built by a wealthy merchant by the name of William M. Galt.[11]

During the 1870s and 1880s, mansions were built along Massachusetts Avenue, one of Washington's grand avenues, and townhouses were built throughout the neighborhood. In 1872, the British built a new embassy on Connecticut Avenue, at N Street NW.[12] Stewart's Castle was built in 1873 on the north side of the circle, the James G. Blaine Mansion was built on the west side in 1882, and the Leiter House was built on the north side in 1893. By the 1920s, Connecticut Avenue was more commercial in character, with numerous shops. Some residences, including Senator Philetus Sawyer's mansion at Connecticut and R Street, were demolished to make way for office buildings and shops.[13] The Patterson House, at 15 Dupont Circle, served as a temporary residence for President Calvin Coolidge while the actual White House was being repaired in 1927.[5] In 1933, the National Park Service took over administering the circle, and added sandboxes for children, though these were removed a few years later.[14]

Connecticut Avenue was widened in the late 1920s, and increased traffic in the neighborhood caused a great deal of congestion in the circle, making it difficult for pedestrians to get around. Medians were installed in 1948, in the circle, to separate the through traffic on Massachusetts Avenue from the local traffic, and traffic signals were added.[14] In 1949, traffic tunnels[15] and an underground streetcar station were built under the circle by Capital Transit, the company produced by the consolidation of D.C.'s streetcar lines. The tunnels enabled trams and vehicles traveling along Connecticut Avenue to pass more quickly past the circle.[16] When streetcar service ended in 1962, the entrances to the underground station were closed. The space has since been transformed and reopened as the Dupont Underground art space.[17]

The neighborhood declined after World War II and particularly after the 1968 riots, but began to enjoy a resurgence in the 1970s, fueled by urban pioneers seeking an alternative lifestyle. The neighborhood took on a bohemian feel and became popular among the gay and lesbian community. Along with The Castro in San Francisco, Hillcrest in San Diego, Greenwich Village in New York City, Boystown in Chicago, Oak Lawn in Dallas, Montrose in Houston, and West Hollywood in Los Angeles, Dupont Circle is considered a historic locale in the development of American gay identity. D.C.'s first gay bookstore, Lambda Rising, opened in 1974 and gained notoriety nationwide.[18] In 1975, the store ran the world's first gay-oriented television commercial.[19]

Gentrification accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s, and the area is now a more mainstream and trendy location with coffeehouses, restaurants, bars, fast casual food, and upscale retail stores. Since 1997, a weekly farmers market has operated on 20th Street NW.[20]

Architecture

editThe area's rowhouses, primarily built before 1900, feature variations on the Queen Anne and Richardsonian Romanesque revival styles. Rarer are the palatial mansions and large freestanding houses that line the broad, tree-lined diagonal avenues that intersect the circle. Many of these larger dwellings were built in the styles popular between 1895 and 1910.

One such grand residence is the marble and limestone Patterson Mansion at 15 Dupont Circle. This Italianate mansion, the only survivor of the many mansions that once ringed the circle, was built in 1901 by New York architect Stanford White for Robert Patterson, editor of the Chicago Tribune, and his wife Nellie, heiress to the Chicago Tribune fortune. Upon Mrs. Patterson's incapacitation in the early 1920s, the house passed into the hands of her daughter, Cissy Patterson, who made it a hub of Washington social life. The house served as temporary quarters for President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge in 1927 while the White House underwent renovation. The Coolidges welcomed Charles Lindbergh as a houseguest after his historic transatlantic flight. Lindbergh made several public appearances at the house, waving to roaring crowds from the second-story balcony, and befriended the Patterson Family, with whom he increasingly came to share isolationist and pro-German views. Cissy Patterson later acquired the Washington Times-Herald (sold to The Washington Post in 1954) and declared journalistic warfare on Franklin D. Roosevelt from 15 Dupont Circle, continuing throughout World War II to push her policies, which were echoed in the New York Daily News, run by her brother Joseph Medill Patterson, and the Chicago Tribune, run by their first cousin, Colonel Robert R. McCormick.

Strivers' Section

editToday's Dupont Circle includes the Strivers' Section, a small residential area west of 16th Street roughly between Swann Street and Florida Avenue. The Strivers' Section was an enclave of upper-middle-class African Americans—often community leaders—in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The area includes a row of houses on 17th Street owned by Frederick Douglass and occupied by his son. It takes its name from a turn-of-the-century writer who described the district as "the Striver's section, a community of Negro aristocracy".

The area, which was once considered an overlap of the Dupont Circle and Shaw neighborhoods, is today a historic district.[21] Many of its buildings are the original Edwardian-era residences, along with several apartment and condominium buildings and a few small businesses.

Landmarks

editTraffic circle

editThe neighborhood is centered around the traffic circle, which is divided between two counterclockwise roads. The outer road serves all the intersecting streets, while access to the inner road is limited to through traffic on Massachusetts Avenue. Connecticut Avenue passes under the circle via a tunnel; vehicles on Connecticut Avenue can access the circle via service roads that branch from Connecticut near N Street and R Street.

The park within the circle is maintained by the National Park Service. The central fountain designed by Daniel Chester French provides seating, and long, curved benches around the central area were installed in 1964.[14] The park within the circle is a gathering place for those wishing to play chess on the permanent stone chessboards. Tom Murphy, a homeless championship chess player, was a resident.[22] The park has also been the location of political rallies, such as those supporting gay rights and those protesting the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

In 1999, Thelma Billy was arrested handing out Thanksgiving dinner to the homeless.[23][24][25] In 2009, a tug of war was sponsored by the Washington Project for the Arts.[26]

In 2014, the city proposed to turn an 850-square-foot (79 m2) concrete sidewalk on the south side of the traffic circle into a "kinetic park". Previously occupied by bike lockers, the parklet was repaved with 100 PaveGen pavers, which generate electricity when people walk on them. Designers ZGF Architects said the project would rebuild the sidewalk and curbs and add seven granite benches, six bollard bicycle racks, and two flower beds. The pavers were expected to "generate 456.25 kilowatts of energy [sic] annually", according to Washington Business Journal, and power lights under each bench.[27][28] The $300,000 project opened in November 2016.[29][30]

Embassies

editThe Dupont Circle neighborhood is home to numerous embassies, many of which are located in historic residences. The Thomas T. Gaff House serves as the Colombian ambassador's residence, and the Walsh-McLean House is home to the Indonesian embassy.[31] Located east of Dupont Circle on Massachusetts Avenue is the Clarence Moore House, now serving as the Embassy of Uzbekistan, and the Emily J. Wilkins House, which formerly housed the Australian embassy and now is occupied by the Peruvian Chancery.[31] Iraq operates a consular services office in the William J. Boardman House on P Street.[32]

Other landmarks

editOther landmarks, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, include the International Temple, Embassy Gulf Service Station, Christian Heurich Mansion (also known as Brewmaster's Castle), Whittemore House (headquarters to the Woman's National Democratic Club), the Brigadier General George P. Scriven House (headquarters to the National Society Colonial Dames XVII Century), and the Phillips Collection, the country's first museum of modern art. The Richard H. Townsend House located on Massachusetts Avenue now houses the Cosmos Club.[31] Across Massachusetts Avenue, the historic Anderson House, owned by the Society of the Cincinnati, is open daily for tours. The Dumbarton Bridge, also known as the Buffalo Bridge, carries Q Street over Rock Creek Park and into Georgetown and was constructed in 1883.[31] The Nuns of the Battlefield sculpture, which serves as a tribute to over 600 nuns who nursed soldiers of both armies during the Civil War, was erected in 1924.[33][34] The Mansion on O Street a luxury boutique hotel, private club, events venue and museum has been a fixture in Dupont Circle for over 30 years and includes over 100 rooms and 32 secret doors. Also overlooking the square is The Dupont Circle Hotel. Two disused semicircular trolley tunnels follow the outline of the circle; the one on the east is currently Dupont Underground, an art and performance space.[35][36]

Institutions

editIn addition to its residential components, consisting primarily of high-priced apartments and condominiums, Dupont Circle is home to some of the nation's most prestigious think tanks and research institutions, including the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Institute for Policy Studies, the Aspen Institute, the German Marshall Fund, the Center for Global Development, the Stimson Center, the Eurasia Center, and the Peterson Institute. The renowned Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) of Johns Hopkins is located less than two blocks from the circle. Dupont Circle is also home to the Founding Church of Scientology museum and Scientology's National Affairs Office. The Phillips Collection, the nation's first museum of modern art, is located near the circle; its most famous and popular work on display is Renoir's giant festive canvas Luncheon of the Boating Party. Additionally, the national headquarters of the Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America, the nation's oldest veterans organization, the National Museum of American Jewish Military History, and the Washington, D.C. Jewish Community Center are also located in Dupont Circle.

Demographics

editDuPont Circle roughly coincides with the following five Census tracts, which had a total population of 15,099 in 2020. The area is roughly 70% non-Hispanic (NH) White, 10% Hispanic, 9% NH Asian, 7% NH Black and 4% NH Multiracial.[37]

| Tract | Location | Total | Hispanic/ Latino |

Non-Hispanic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One race alone | Multi- racial | |||||||||

| White | Black | American Indian | Asian | Pacific Islander | Some other race | |||||

| 42.01 | From S St to Florida and 16th to 18th St | 3,548 | 334 | 2,597 | 194 | 3 | 259 | 0 | 9 | 152 |

| 42.02 | N of Circle | 2,850 | 279 | 2,070 | 110 | 2 | 242 | 1 | 14 | 132 |

| 53.02 | E of Circle, from Q St to S St | 2,518 | 236 | 1,857 | 117 | 6 | 176 | 0 | 14 | 112 |

| 53.03 | E of Circle, from Q St to Mass. Ave | 3,215 | 332 | 2,047 | 301 | 4 | 380 | 3 | 17 | 131 |

| 55.02 | W of Circle | 2,968 | 293 | 1,977 | 292 | 1 | 257 | 0 | 19 | 129 |

| Total population of the 5 census tracts | 15,099 | 1,474 | 10,548 | 1,014 | 16 | 1,314 | 4 | 73 | 656 | |

| Racial/ethnic groups as % of total pop. | 100% | 9.8% | 69.9% | 6.7% | 0.1% | 8.7% | 0.03% | 0.5% | 4.3% | |

Note: "Circle" refers to the Dupont Circle traffic circle. Source: 2020 decennial Census

Transportation

editDupont Circle is served by the Dupont Circle station on the Red Line of the Washington Metro. There are two entrances: north of the circle at Q Street NW and south of the circle at 19th Street NW. The northern entrance is framed by a quote from Walt Whitman's 1865 poem, "The Wound-Dresser", that was carved into the entrance in 2007 and echoes the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s.[38]

Annual neighborhood events

editCapital Pride

editCapital Pride is an annual LGBT pride festival held each June in Washington. As of 2007[update], the festival is the fourth-largest LGBT pride event in the United States, with over 200,000 people in attendance.[39] The Capital Pride parade takes place annually on Saturday during the festival and travels through the streets of the neighborhood.[40] Dupont Circle is host to the parade, and the street festival is held in Penn Quarter.

High Heel Race

editHeld annually since 1986, the Dupont Circle High Heel Race takes place on the Tuesday before Halloween (October 31). The race pits dozens of drag queens against each other in a sprint down 17th Street NW between R Street and Church Street, a distance of three short blocks. The event attracts thousands of spectators and scores of participants.[41][42]

See also

edit- The Anchorage

- Dupont Circle Building

- The Dupont Circle Hotel

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Washington, D.C.

- The Real World: Washington, D.C., television series filmed in Dupont Circle in 2009

- Architecture of Washington, D.C.

References

edit- ^ a b c "Dupont Circle Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ Ramsdell, Henry J.; Benjamin Perley Poore (1884). Life and Public Services of Hon. James G. Blaine. Hubbard Brothers. p. 173.

- ^ Lanius, Judith H.; Sharon C. Park. "Martha Wadsworth's Mansion: The Gilded Age Comes to Dupont Circle". Washington History: 24–45.

- ^ Evelyn, Douglast E.; Paul Dickson; Evelyn Douglas; S J Ackerman (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Capital Books. p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Proctor, John Clagett (July 25, 1937). "Dupont Circle Memorial". Washington Evening Star. p. 46. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ "Local History: Neighborhoods, Dupont Circle". ExploreDC.org. WETA Public Broadcasting. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ When the White House's roof and upper floor were under construction in 1927, President Calvin Coolidge and his wife lived at 15 Dupont Circle for six months."Coolidges Have New Address". The Meriden Daily Journal, via Google News. Meriden, Connecticut. Associated Press. March 3, 1927. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Dupont Circle". connavedotcom. 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ^ "Scenes from the Past" (PDF). The InTowner. March 2004. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Gallery of Art Unique in Design: Quaint Structure of Stucco Contains Many Rare Objects", The Washington Times, 18 November 1906, archived from the original on 2021-04-22, retrieved 2021-04-22. This structure was later replaced by an automobile show room, now a Starbucks coffeehouse.

- ^ "The Galts and Galts of Dupont Circle". InTowner Publishing Corp. 2014-03-17. Archived from the original on 2019-04-06. Retrieved 2019-04-06.

- ^ Goode, James M. (1979). Capital Losses: A Cultural History of Washington's Destroyed Buildings. Smithsonian Institution. p. 231.

- ^ "Scenes from the Past" (PDF). The InTowner. March 2008. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c Bednar, Michael J. (2006). L'Enfant's Legacy. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 181.

- ^ "Historical Photo Archives". District Department of Transportation. 2007-11-26. Archived from the original on 2007-11-26. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ "D.C. Transit Track and Structures". BelowTheCapital.org. 2008-04-01. Archived from the original on 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ The Dupont Circle Metro Station is completely separate from the former underground streetcar station; Metrorail trains operate nearly 200 feet (61 m) underground, far deeper than the original streetcars."WMATA Facts" (PDF). WMATA. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-05-27. In 1995, developer Geary Simon renovated the streetcar station as a food court called "Dupont Down Under"; the project failed, and was shut down a year later.Kelly, John (2003-12-28). "What is 'Dupont Down Under' and What Makes Metro Stations Windy?". The Washington Post. p. M09. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2008-06-23. In 2007, plans circulated to transform the underground area into a number of adult clubs, possibly to replace several gay bars that were forced out by the building of the Nationals Park baseball stadium. However, opposition from the community largely stalled any further planning, and the space remains unused."Adult clubs in Dupont Down Under?". The Washington Times. 2007-07-14. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ "Dupont Circle/Sheridan-Kalorama". Cultural Tourism DC. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Muzzy, Frank. Gay and Lesbian Washington D.C., Arcadia Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7385-1753-4

- ^ Kettlewell, Caroline (2003-06-27). "Harvest Home". The Washington Post.[dead link]

- ^ Section, Striver's. "Striver's Section". www.cr.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Tower, Wells (September 30, 2007). "The Days and Knights of Tom Murphy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Loose, Cindy (1999-11-25). "Hassles Over Feeding the Hungry Are Warmly Rewarded". Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ^ Riechmann, Deb (1997-03-16). "Kind Act Grows into Hunger Crusade". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ "Thelma vs. the Park Police". The Washington Times. January 14, 1997.

- ^ Marchand, Anne (April 18, 2009). "Tug-Of-War At WPA". Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Neibauer, Michael (August 21, 2014). "Step On It: D.C. Plans 850-Square-oot, $200K Kinetic Pocket Park at Dupont Circle". Washington Business Journal. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Meagan (November 18, 2016). "From Your Feet to the Light Bulb: Dupont Park Uses Kinetic Energy to Light Up Sidewalk". NBC4. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Michael Laris (November 30, 2016). "This Dupont Circle sidewalk turns footsteps into power". The Washington Post.

- ^ Tim Regan (November 18, 2016). "Kinetic Tiles Now Generating Electricity at Dupont 'Pocket Park'". Borderstan. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "DC Geographic Information System (GIS), Historic Structures". District of Columbia, Office of the Chief Technology Officer. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ "Contact Us". Embassy of the Republic of Iraq. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ^ Save Outdoor Sculpture! (1993). "Nuns of the Battlefield, (sculpture)". SOS!. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Jacob, Kathryn Allmong. Testament to Union: Civil War monuments in Washington, Part 3. JHU Press, 1998, p. 125-126.

- ^ "Dupont Underground debuts World Press Photo exhibition". dc.curbed.com. 2017-11-07. Archived from the original on 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ "What You Need to Know About Dupont Circle's Secret Tunnels". dc.curbed.com. 2014-08-12. Archived from the original on 2018-03-10. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ "Census Tract Map of the District of Columbia, 2020" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-1626199736.

- ^ Chandler, Michael Alison (June 11, 2007). "Street Fest Lets Gays Revel in Freedom". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "Parade Route Map". Metro Weekly. June 4, 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "High Heel Race DC". Archived from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

- ^ "25th Annual D.C. High Heel Drag Queen Race 2011". DC Metromix. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

Further reading

edit- Dupont Circle: A Novel (Houghton Mifflin, 2001), by Paul Kafka-Gibbons

- Dupont Circle (Images of America Series) (Arcadia Publishing, 2000), by Paul Williams

- Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C. (U.S. Department of the Interior, Division of History, Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, 1967), by George J. Olszewski

External links

edit- Dupont Circle Business Improvement District

- Historic Dupont Circle Main Streets

- Dupont Circle Advisory Neighborhood Commission (local elected government)

- Dupont Circle Citizens Association

- Dupont-Kalorama Museums Consortium

- NPS Dupont Circle Historical District

- WETA Neighborhoods - History of Dupont Circle

- Dupont Circle Metro station

- Washington Post's Guide to Dupont Circle

- D.C. High Heel Drag Queen Race Photo Galleries

- History of Dupont Circle Documentary produced by WETA-TV