This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

The Duchy of Nassau (German: Herzogtum Nassau) was an independent state between 1806 and 1866, located in what became the German states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse. It was a member of the Confederation of the Rhine and later of the German Confederation. Its ruling dynasty, later extinct, was the House of Nassau.[1][2] The duchy was named for its historical core city, Nassau, although Wiesbaden rather than Nassau was its capital. In 1865, the Duchy of Nassau had 465,636 inhabitants. After being occupied and annexed into the Kingdom of Prussia in 1866 following the Austro-Prussian War, it was incorporated into the Province of Hesse-Nassau. The area is a geographical and historical region, Nassau, and Nassau is also the name of the Nassau Nature Park within the borders of the former duchy.

Duchy of Nassau Herzogtum Nassau (German) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1866 | |||||||||||||

| Status | State of the Confederation of the Rhine (1806–1813) State of the German Confederation (1815–1866) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Weilburg (1806–1816) Wiesbaden (1816–1866) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Moselle Franconian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||

• 1806–1816 | Frederick Augustus | ||||||||||||

• 1816–1839 | William | ||||||||||||

• 1839–1866 | Adolph | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Modern era | ||||||||||||

• Established | 30 August 1806 | ||||||||||||

| 23 August 1866 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Kronenthaler | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg still uses "Duke of Nassau" as his secondary title, and "Prince" or "Princess of Nassau" is used as a title by other members of the grand ducal family. Nassau is also part of the name of the Dutch royal family, which styles itself Orange-Nassau.

Geography

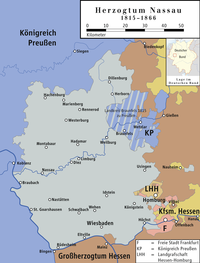

editThe territory of the duchy was essentially congruent with the Taunus and Westerwald mountain ranges. The southern and western borders were formed by the Main and the Rhine, while in the northern part of the territory, the Lahn river separated the two mountain ranges. The neighbouring territory to the east and south was the Grand Duchy of Hesse. The Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg and the Free City of Frankfurt were also to the east. To the west was the Rhine Province of the Kingdom of Prussia, which also controlled an exclave in the eastern part of Nassau, called Wetzlar.

Population

editAt its foundation in 1806, the Duchy had 302,769 inhabitants. The citizens were mostly farmers, day labourers, or artisans. In 1819, 7% of Nassauers lived in settlements with more than 2,000 inhabitants, while the rest lived in 850 smaller settlements and 1,200 isolated homesteads. Wiesbaden, with 5,000 inhabitants, was the largest settlement and Limburg an der Lahn, with around 2,600 inhabitants, was the second-largest. By 1847, Wiesbaden had grown to 14,000 inhabitants and Limburg to 3,400. The third-largest city was Höchst am Main.

History

editEstablishment

editThe House of Nassau produced many collateral lines in the course of its nearly one-thousand-year history. Up to the 18th century, the three main lines were the small princedoms of Nassau-Usingen, Nassau-Weilburg, and Nassau-Dietz (later Orange-Nassau), with large, scattered territories in what is now the Netherlands and Belgium. From 1736, many treaties and agreements were made between the different lines (The Nassau Family Pact), which prevented further splitting of territories and enabled general political co-ordination between the branches. In this context, the administrative subdivisions of the individual territories were adjusted, laying the foundations for the later unification of the territories.

After the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797), Nassau-Dietz lost its possessions in Belgium and the Netherlands, while Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Weilburg lost all their territories west of the Rhine to France. On the other hand, like other German secular principalities, the Nassaus gained territory that had formerly belonged to the church as a result of secularisation. The Nassaus participated in negotiations at the Second Congress of Rastatt (1797) and in Paris, in order to secure the territories of the Prince-Bishops of Mainz and Trier. The Imperial Recess of 1803 largely accorded with the desires of Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Weilburg. Orange-Nassau had already agreed separate terms with Napoleon.

Nassau-Usingen had lost Saarbrücken, two-thirds of Saarwerden, Ottweiler, and some smaller territories (totalling 60,000 inhabitants and 447,000 guilders of income per year). In compensation, it received: from Mainz, Höchst, Königstein, Cronberg, Lahnstein and the Rheingau; from Cologne some districts on the east bank of the Rhine; from Bavaria, the sub-district of Kaub; from Hesse-Darmstadt, the lordship of Eppstein, Katzenelnbogen, and Braubach; from Prussia, Sayn-Altenkirchen, Sayn-Hachenburg; and several cloisters were received from Mainz. Thus Nassau-Usingen regained its lost population and increased its annual income by around 130,000 guilders.

Nassau-Weilburg lost Kirchheim, Stauf, and its third of Saarwerden (15,500 inhabitants and 178,000 guilders in revenue). For these, it received many small possessions of Trier, including Ehrenbreitstein, Vallendar, Sayn, Montabaur, Limburg an der Lahn, three abbeys, and the holdings of Limburg Cathedral. This totalled 37,000 inhabitants and 147,000 guilders of revenue.

In the course of these arrangements, the Kammergut of the Princely house was considerably extended to more than 52,000 hectares of forests and agricultural land. These domains encompassed 11.5% of the flat land and yielded around a million guilders per year – the largest part of their total income.

Even before the actual Imperial Recess, in September and October 1802, both principalities deployed troops in the territories of Cologne and Mainz that they had received. In November and December, after civilian officials had taken possession of the territory, new oaths were sworn by officials of the previous regimes and the new subjects. According to the reports of Nassau officials, the new administrations were welcomed, or at least accepted without protest, in most regions, since the Nassau principalities were considered very liberal, compared to the former ecclesiastical rulers. Between December 1802 and September 1803, the wealth monasteries and religious communities were disbanded. The closures of monasteries without possessions continued until 1817 since the state had to provide pensions to monks and converses after disbanding their communities. Between October 1803 and February 1804, the territories of many Imperial Knights and other possessors of Imperial immediacy were occupied and annexed. Only in August/September 1806 were these acquisitions confirmed by edict, affirmed by the treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine. This process encountered considerable resistance, led by the Imperial Knights, but this resistance had no serious consequences and ultimately failed since the Nassau princes' seizures were enforced by French officials and soldiers.

On 17 July 1806, Prince Frederick Augustus of Nassau-Usingen and his cousin Prince Frederick William of Nassau-Weilburg joined the Confederation of the Rhine. Prince Frederick Augustus, the senior member of the House of Nassau received the title of Sovereign Duke of Nassau, while Frederick William was granted the title of Sovereign Prince of Nassau. Under pressure from Napoleon I both counties merged to form the Duchy of Nassau on 30 August 1806, under the joint rule of Frederick Augustus and Frederick William. This decision was encouraged by the fact that Frederick Augustus had no male heirs and Frederick William was thus in line to inherit his principality anyway.

In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, there was a further territorial expansion. When the Orange-Nassau line received the Dutch crown on 31 May, they had to surrender the Principality of Orange-Nassau to Prussia, which passed part of it to the Duchy of Nassau the next day.

Frederick William died from a fall on the stairs at Schloss Weilburg on 9 January 1816, and it was his son William who became the first sole Duke of Nassau after Frederick Augustus' death on 24 March 1816.

Reform period

editThe Chief ministers in 1806 were Hans Christoph Ernst von Gagern and Ernst Franz Ludwig von Bieberstein. Von Gagern resigned in 1811, after which von Bieberstein served alone until his death in 1834.

A series of reforms were carried out in the first years of the Duchy: the abolition of serfdom in 1806, the introduction of freedom of movement in 1810, and a fundamental tax reform in 1812, which replaced 991 direct taxes with a single progressive tax on land and trade. Degrading corporal punishment was abolished and the Kulturverordnung (cultivation ordinance) promoted the autonomous management of soil and land. After a transitional period with four districts, the new Duchy was consolidated into three districts on 1 August 1809: Wiesbaden, Weilburg, and Ehrenbreitstein. In turn, these were abolished in 1816, with the establishment of Wiesbaden as sole capital. The number of Amt subdivisions was slowly reduced, from sixty-two in 1806 to forty-eight in 1812. Due to the religious heterogeneity of the territory, a system of "combined schools" was introduced on 24 March 1817. On 14 March 1818, a state-wide public health system was established – the first such system in Germany.

Constitution of 1814

editOn 2 September 1814, a constitution was promulgated. It was the first modern constitution in any of the German states. Because there was (very limited) parliamentary involvement in government, especially in taxation, it was considered to be a "Parliamentary Constitution" in the language of the day. The constitution guaranteed the freedom of the individual, religious tolerance, and the freedom of the press. It was heavily influenced by Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein, who originally came from Nassau and had substantial holdings there. The princes encouraged his involvement because he was part of the class of Imperial Knights who had been dispossessed by them and due to his involvement, the opposition of the Knights was diminished. However, the legislation of the Concert of Europe period, especially the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819, marked a new restriction of freedoms in Nassau as elsewhere.

On 28 December 1849, the constitution was replaced by a reformed constitution which took account of the democratic demands of the German revolutions of 1848–49. On 25 November 1851, this constitution was repealed and the old constitution was restored.

Parliament

editUnder the constitution of 1814, the Parliament (Landstände) of Nassau had two chambers: a chamber of deputies (Landesdeputiertenversammlung) and a house of lords (Herrenbank). The eleven members of the house of lords were all princes of the House of Nassau or representatives of the nobility. The twenty-two members of the chamber of deputies were mostly elected by census suffrage but had to be land owners, except for three representatives of ecclesiastics and one representative of teachers.

Only four years after the establishment of the constitution, in 1818, did the first election in the Duchy take place. As a result, Parliament was prevented from playing a role in the establishment of the Duchy. The electorate consisted of 39 nobles, 1448 owners of substantial amounts of land, and 128 wealthy city dwellers. Given that the population of the Duchy at the time was about 287,000, this was a tiny number of electors.

The Parliament met for the first time on 3 March 1818.

The Nassau Domain dispute

editAt the foundation of the Duchy, Minister von Bieberstein established a strong fiscal distinction between the treasury of the general domain and that of the regional taxes. The domain, which included court estates and land, and mineral water springs, as well as the tithe and other feudal dues was the property of the Ducal House, which could not be used for paying state expenses and which Parliament had no power over. Even in the very earliest years of the Duchy, this system was loudly criticised. The parliamentary president Carl Friedrich Emil von Ibell in particular complained about this in letters to Bieberstein and petitions to the Duke, with ever greater frequency. His hostile position was one of the justifications for his impeachment in 1821.

In the following years, there was more debate with and within Parliament, as well as with the government, about the division between Ducal and state funds. The conflict only came out into the open, however, in the course of the July Revolution of 1830 sparked unrest in neighbouring countries. In 1831, the government prevented the submission of petitions to the Duke on the subject and held a joint manoeuvre in Rheingau with Austrian troops from the fortress in Mainz. At its next sitting, Parliament, which had not been very active up to this point, drafted several reform proposals, few of which were accepted. The issue of the Domain thus progressed to burning point. On 24 March, the deputies of the lower chamber put forward a proposal for the Domain to become property of the populace. The government forbade a public assemblies on this issue and announced the opposite opinion. To suppress any revolt following this decision, several hundred troops were called in from the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Hesse. However, no revolt actually broke out. In the press within the state and in the neighbouring principalities, articles in newspapers and pamphlets supported both sides of the issue.

The president of the chamber Georg Herber was the main figure on the side of the deputies, especially in a polemical piece published in the Hanauer Zeitung on 21 October 1831. At the end of 1831, the Nassau court began investigations against Herber. On 3 December 1832, Herber was finally sentenced to three years in prison for 'Abuse of the sovereign' and 'libel' against Bieberstein. On the night of 4 December, the president of the chamber was arrested as he slept in his bed. On 7 January 1833, he was released on bail. Herber's lawyer, August Hergenhahn, later the revolutionary Chief Minister of Nassau, attempted to get him a reduced sentence, but he was prevented. However, the sentence was never enforced, because Herber, who was very sick, died on 11 March 1833.

The Ducal government had already prepared to expand the house of lords in the course of 1831 and this was effected by an edict on 29 October 1831. The bourgeois were thus put into a minority and failed in their attempt to prevent the levying of taxation in November 1831. Additionally, the house of lords voted down a targeted action of the bourgeois against Bieberstein. In the following months, there were ever more assemblies, rallies, newspaper articles (especially from outside Nassau), and pamphlets by the different parties of the conflict. Officials who had expressed sympathies for the bourgeois were reprimanded or fired and liberal newspapers from outside Nassau were banned.

In March 1832, there was a new election for the lower chamber. However, the bourgeois deputies demanded that the house of lords were reduced to their previous numbers. Since the government refused this, the deputies ended the session and left the chamber on 17 April. The three ecclesiastical members, the member for teachers and one other deputy declared that the rest had forfeited their right to participate and approved the Ducal tax levy.

Accession of Duke Adolphe

editAfter the Domain Dispute, the politics of Nassau became quiet. After the death of von Bieberstein, Nassau entered the German Zollverein in 1835, which Bieberstein had energetically resisted. In 1839, Duke William also died and his twenty-two-year-old son Adolphe replaced him as Duke. Adolphe moved his residence to the Wiesbaden City Palace in 1841 and in January 1845, he married the Russian Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mikhailovna, who died in childbirth a year later. To honour her, he had the Russian orthodox church in Wiesbaden. In 1842, Adolphe was one of the founding members of the Mainz Adelsverein, which was intended to establish a German colony in Texas, but was not successful.

From 1844, there was a wave of community foundations in Nassau, especially trade and athletic associations. These were initially apolitical, but they would play a role in the upcoming Revolution. Wiesbaden was additionally one of the centres of German Catholicism. The government attempted some tentative reforms in 1845 with a somewhat more liberal municipalities law and with a law about district courts in 1846. In 1847, Parliament drafted laws on press freedom and damage to the land by animals, in response to complaints from the rural population about the consequences of Ducal hunts.

Revolution of 1848

editLike most of Europe, Nassau was engulfed in a revolutionary wave after the February Revolution in France in 1848. On 1 March a liberal group headed by the jurist August Hergenhahn gathered at the Vier Jahreszeiten Hotel in Wiesbaden to present a list of moderate liberal nationalist demands to the government. This list included civil freedoms, a German national assembly, and a new electoral law. The next day, the Neun Forderungen der Nassauer (Nine Demands of the Nassauers) were presented to Chief Minister Emil August von Dungern, who immediately approved the formation of a citizens' militia, freedom of the press, and the convocation of the lower chamber of Parliament to discuss electoral reform. Decisions on the other demands were reserved for the Duke, who was in Berlin at that moment.

In accordance with a proclamation of Hergenhahn, around 40,000 men assembled in Wiesbaden on 4 March. There was a clear conflict in this action, which would shape the subsequent development of events: while the circle around Hergenhahn hoped to receive confirmation of their demands by the acclamation of the people, they were mainly peasants, armed with scythes, cudgels, and axes, seeking the abolition of old Feudal impositions and an easing of forest and hunting laws. As the crowd moved restlessly through the city, the Duke announced from the balcony of his residence that he would meet all their demands. Then the crowd happily dispersed.

With the advent of press freedom, thirteen political newspapers appeared within weeks, including five in Wiesbaden alone. Numerous local gazettes in rural areas also began to print political texts.

From the second week of March, electoral reform took centre stage in the political scene. The most important demand of the liberals was that the right to vote should no longer be tied to a minimum property requirement. On 6 March, the lower chamber held a debate on this subject. When the house of lords sought to discuss voting rights as well, there were protests among the populace of Wiesbaden. Around 500 people gathered in Wiesbaden in the evening to publicly debate the question of voting rights. Smaller meetings occurred in other cities of nassau. By the middle of the month however, these public discussions had faded away. Meanwhile, the lower chamber agreed that the future parliament should be unicameral with 40–60 members and that the property requirement for voting should be abolished. Most controversial was whether the members of the new parliament should be elected directly or by an electoral college. A draft bill was presented on 20 March and finally passed on 28 March. They decided in favour of an electoral college by 18 votes to three. On 5 April the electoral law came into effect. It stated that every hundred people would choose an elector, who in turn would meet in one of 14 electoral colleges, each of which would choose one member of parliament. The right to vote was extended to several groups that had hitherto been excluded, such as noblemen, officials, pensioners, and Jews. Those who received poor relief or were bankrupt were not allowed to vote. All citizens were eligible to serve as members of Parliament except for the highest administrative officials, military officers, and court officials.

Meanwhile, on 31 March, the Pre-Parliament gathered in the St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt-am-Main. Fifteen of its deputies were drawn from the lower chamber of the Nassau parliament and two from the Nassau house of lords. There were another nine citizens of the Duchy in the Pre-Parliament as well.

As a result, chaotic conditions developed in rural areas. Many officials had lost their jobs at the beginning of the revolution, so there was no ordered administration. The farmers completely stopped paying taxes and drove out the forest rangers. Many young officials and teachers proved to be revolutionary agitators for a radical democracy. The Ducal government contributed to this situation with hectic actions to calm the rural population, like amnesties (particularly for poaching, rural, and forest crimes), conceding free elections of the Schultheißen, the abolition of the last feudal dues, and the removal of various unpopular administrative officials. In the cities, the people often reacted to the general lawlessness by establishing their own neighbourhood watches. In Wiesbaden, a central safety committee for the whole of Nassau under the leadership of Augustus Hergenhahn was established and came to enjoy a level of authority throughout the Duchy. Hergenhahn developed into the moderate liberal leading light of the revolution and also secured the trust of Duke Adoplhe. After Emil August von Dungern resigned as Chief Minister, the Duke appointed Hergenhahn as his replacement on 16 April.

1848 elections

editSince the elections for the Parliament of Nassau were drawing near, political societies began to form and these eventually consolidated into true political parties. From the end of March, the Bishop of Limburg, Peter Joseph Blum, began to encourage Catholic societies in rural areas. They had the clearest programme of any of the parties, with 21 core principles, which the Bishop had promulgated on 9 March. Additionally, pastoral letters and religious services provided a platform for propagating ecclesiastical politics. On 4 April, a radical liberal pamphlet was distributed in Wiesbaden, announcing the "Committee of the Republican Society" as the first party that stood against the Catholic political agitation. The next day, a special issue of the Nassauische Allgemein announced a Democratic-Monarchist opposition party, which was formally founded on 7 April. On 5 April, there were significant protests calling for the establishment of a Wiesbaden committee for electoral preparation. In the morning, the Liberals called for a public assembly to take place at 1 pm, at which the electoral college would be chosen for which they had already prepared a list of candidates. In midmorning, the Moderates secured a two hour postponement, which they used to draft their own list, which secured a large majority of the votes when the meeting took place.

In the following weeks, the Ducal government began preparations for the Parliamentary elections and for elections to the Pan-German Frankfurt Parliament. Since this was the first time that such a task had been attempted, it was an incredibly difficult process in many areas to create the lists of voters. There were protests by the populace and newspapers against limitations on the right to vote that were considered unfair. In particular, they pushed back against the fact that the adult sons of artisans and farmers would not be allowed to vote if they worked in their father's business.

Finally, on 18 April, the election of the electoral colleges took place. In each town and region they were chosen by assemblies of voters. The total number of the 420,000 inhabitants of the Duchy who voted could not be determined for certain. Estimates varied between 84,000 and 100,000 people (20–23%). Turnout varied by region from very low to nearly full participation, but there was a tendency for higher participation in the cities than in the countryside. Many procedural irregularities were reported from the electoral assemblies. Ideological programmes played a minor role in the selection of electors. Promises of lower rates of taxation were thrown around in many of the hustings during the assemblies. In most cases they elected people who were already socially prominent, like mayors, teachers, forest rangers, or clergymen (especially in the Westerwald). The Catholics provided their followers with pre-prepared ballot papers with the Catholic candidates marked on them. This was explicitly forbidden by the electoral law and was strongly criticised by the liberals.

The 4,000 electors chose the six representatives of Nassau for the Frankfurt Parliament on 25 April. It proved difficult to find suitable and willing candidates. Only with difficulty did the Wiesbaden electoral committee (as representatives of the moderate liberals, the Catholic church and its societies, and the various ideological newspapers) find candidates for the six vacancies. Everyone in the committee's list was a government employee.

In District 1 (Rennerod, in the north of the duchy) and District 4 (Nastätten, southwest), there was not much conflict; Procurator Carl Schenck of Dillenburg was elected in the former with 76% of the vote, while Friedrich Schepp, a member of the governing council, was chosen in the latter with 90% of the vote. In District 2 (Montabaur, in the northwest), there had been a much more heated campaign, but Freiherr Max von Gagern won with 82% of the vote. Von Gagern had been approached to be a candidate by the liberals, but was also a devoted Catholic and close confidant of the Duke. This position between the camps provided opportunities for Catholics and Liberals to attack him, but these attacks ultimately had little impact, since he retained the church's support. Controversy also surrounded Friedrich Schulz, the committee's candidate for District 3 (Limburg, in the centre of the duchy). He was a deputy headmaster in Weilburg and editor of the Lahnboten, who pushed a reformist line, which in his opinion would lead to a Republic. For this ambitious plan, which was criticised as "fantastical", Schulz was criticised by the liberals. But in the end, Schulz secured 85% of the vote in his district. District 5 (Königstein, the southeast) was won by Karl Philipp Hehner, who held the most radical views of any of the representatives. He was a former member of a Burschenschaft and had been temporarily expelled from state service in 1831 for his political views, but had risen by March 1848 to one of the highest positions in the government. Hehner considered a constitutional monarchy as only a transitional stage and kept his main focus on a Republic. Probably because of this radical position, he secured only 61% of the vote in his district. In District 6 (Wiesbaden), Augustus Hergenhahn himself stood and won with 80% of the vote.

In the course of 1848, the Nassau deputies in the Frankfurt Parliament aside from Schenk developed into factions. Von Gagern, Hergenhahn and Schep joined the moderate liberal Casino faction, while Schulz and Hehner joined the centre left Westendhall. As the Frankfurt Parliament collapsed, Max von Gagern resigned his position along with 65 other monarchist representatives on 21 May 1849. He was followed shortly after by Hergehahn, Schepp and Schenk. Hehner and Schulz remained members until the final dissolution of the Parliament in June 1849.

In the election for the Nassau parliament on 1 May, which was also carried out by the 4,000 members of the electoral colleges, local interests played a much larger role than in the elections for the Frankfurt Parliament. The parties and societies did not have a serious impact. The majority of the successful candidates were civil servants and mayors, with a couple of merchants, industrialists, and farmers. Noticeably few Catholics and absolutely no Catholic clergy were elected.

End of the Revolution

editThe Nassau Parliament met for the first time on 22 May 1848. Over the summer, groupings based on the Left-Right schema began to appear in the parliament. The unrest in Nassau was not calmed after the elections. In July 1848, it reached a new crisis point, with physical clashes on the right of the Duke to veto decisions of Parliament. While the left wing in the Parliament did not recognise this power, the right wing and the Ducal government insisted on it. Soon this dispute led to unrest among the general population. Finally, Hergenhahn called in Prussian and Austrian troops from Mainz, who put down the riots in Wiesbaden. In September, after fighting in the streets in Frankfurt, Federal troops occupied part of the Taunus.

In parallel with the Parliament, the landscape of political societies and publications also began to develop a firmer ideological divide and became increasingly active. Many petitions and rallies took place in the second half of the year. The Freie Zeitung became the mouthpiece of the left wing of the National assembly over the course of the summer and frequently criticised the governments of Prussia and Nassau. The Nassauische Allgemeine abandoned strict neutrality and transformed into a supporter of a constitutional monarchy, as did the Weilburg Lahnbote. Even in 1848, an abatement of the revolutionary force was notable. Except for the Freie Zeitung and the Allgemeine all papers ceased publishing in the second half of the year, because sales rapidly dropped and the Ducal government began to suppress the press. As a result of these developments, the Nassauische Allgemeine became increasingly dependent on the Ducal government for money and content. From the end of 1849, there was again a comprehensive censorship regime.

The political societies, which had formed by autumn 1848, mostly took up democratic positions, including explicitly political clubs, but also many sports clubs and workers' clubs. On 12 November, the democratic societies joined together as the Kirberger Union, which was to serve as an umbrella organisation. As the reaction against the revolution began, there were many new foundations, so that by the end of 1848, there were around fifty organisations in the Kirberger Union, many with their own sub-organisations. In the following months however, the democratic movement collapsed rapidly. After the middle of 1849, there were no active democratic societies. A few societies were formed, supporting constitutional monarchy. They gained an over-arching structure on 19 November 1848, when the Nassau and Hessian constitutional societies named themselves the Deutsche Vereine (German Society) as an umbrella organisation with its base in Wiesbaden.

Elections for the Erfurt Parliament

editAfter the collapse of the Frankfurt Parliament, there was conflict between Prussia, Austria, and the smaller German states. The Duchy of Nassau was among the small German principalities which supported the Prussians and their plans to convoke a Union Parliament at Erfurt. On 3 December 1849, the Ducal government oversaw elections for this body in the four Nassau districts, using Prussian three-class franchise

Although the political movements had passed their peak, there was even so an electoral campaign for the positions. Constitutionalists, the government and the Nassauische Allgemeine all sought a high voter turnout in the hope that this would add legitimacy to the Prussian plans for a monarchist Germany. The so-called Gotha Post-Parliament, an informal successor of the Frankfurt Parliament, came decisively under the influence of Max van Gagern. August Hergenhahn also participated in that Post-Parliament in June 1849. On 16 December, the constitutional monarchists organised a large electoral assembly in Wiesbaden, at which nominations took place. By contrast, the democrats tried to ensure a low voter turnout and sought the implementation of the Frankfurt Constitution. In June 1849, the organised people's assemblies all over Nassau for this purpose. The largest assembly, with around 500 participants, took place on 10 June in Idstein and formulated ten demands, including the withdrawal of Nassau troops from Baden, Schleswig-Holstein, and the Palatinate, where they were stationed as representatives of the German Federation to prevent revolutionary movements. Beyond that, they wanted the reconstitution of a German parliament with full powers. The Catholic political societies had already disappeared by this point. The church itself made no effort to influence the election.

Preparation for elections to the Erfurt Parliament began in December 1849. On 20 January 1850, the initial election of the electoral college took place in Nassau. Due to the higher voting age, the number of voters participating was a bit lower than in 1848. The turnout varied between 1% and 20%. Only two districts had a turnout of more than 60%. In some places, the only participants were the polling officials themselves. In at least 27 of the 132 electoral districts, the vote could not take place at all because of low turnout and had to be rescheduled for 27 January. The men chosen to be members of the electoral colleges were all civil servants. In the following days, the constitutional monarchists nominated candidates to be elected as representative. On 31 January, the electoral colleges chose Carl Wirth, a local official in Selters, Max von Gagern, August Hergenhahn and the Duke's brother-in-law Hermann, Prince of Wied as Nassau's deputies to the Erfurt Parliament. Although a nobleman, the Prince of Wied was the most liberal of the elected representatives.

The Restoration

editAfter a brief period of calm, Duke Adolphe began a reactionary programme. There were ever more conflicts between the Duke and the Chief Minister Friedrich von Wintzingerode who was only moderately conservative and resigned at the end of 1851. His successor was August Ludwig von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg, who took his position on 7 February 1852. With his help, the Duke reduced the freedoms that had been granted over the following years and began to remove liberal officials from office. By the middle of 1852, nearly all political societies had been banned.

In 1849, the government submitted a proposal for new elections to Parliament, which were to elect a bicameral system in which the upper chamber would be elected by wealthy citizens. This proposal was opposed by the Liberals, while the constitutional monarchists supported it. After that there was no further discussion about elections until September 1850, when the government submitted a new proposal for a twenty-four member chamber elected using the Prussian three-class franchise, modelled on the Erfurt Parliament. There was no further consultation with Parliament about the new elections, since the Duke dissolved Parliament on 2 April 1851. On 25 November, the Duke finally brought regulations into effect for the election of a Parliament similar to the bicameral system that existed before 1848. The political groups and the few remaining societies made no attempt at campaigning. On 14 and 16 February 1852 the landowners and merchants in the highest tax-bracket (less than a hundred people in the whole duchy) voted first for the six members of the upper chamber. The electoral college for the lower house was elected on 9 February and the elected college met on 18 February. The eligible voters for the lower chamber numbered 70,490. Voter turnout was between 3–4%. In some areas, lack of interest meant that the elections could not take place at all. Unlike the previous Parliament, farmers were the largest group in the new lower house.

Bitter political strife returned once more in 1864, when the Government made plans to sell Marienstatt Abbey in the Westerwald. It had been secularised in 1803 and passed into private ownership. In 1841 the site was put up for sale and the government made plans to turn the abbey into the first state-run home for the elderly and poor in Nassau. The Minister of Construction estimated the costs for the required renovations at 34,000 guilders. In 1842, the Duchy bought the Abbey for 19,500 guilders. Shortly after that it was reported the buildings were in too bad a condition for the project. By the 1860s, the buildings had declined even further. The diocese of Limburg began to be interested in acquiring it, in order to make it into an orphanage. The government was also interested in selling it because of the costs of maintaining the unused complex. The abbey was sold on 18 May 1864 for 20,900 guilders.

Shortly before this, in the 25 November 1863 elections, the liberals had won a large majority in the lower chamber of Parliament. Their manifesto had proposed, among other things, that the privileges held by the Catholic church should also be extended to other religious groups. On 9 June 1864, the liberals in parliament argued that the sale of the Abbey should not be completed. They argued that the buildings and estate were worth more than the price that they had been sold for, and that Parliament had a right to veto sales of land. The government's officials denied that Parliament had any such right and stressed the social value that the structure would have after its sale. In the course of the debate, which continued over several sittings, a fierce war of words developed between the pro- and anti-clerical members of Parliament. The anti-clerical members disapproved of giving the Catholic church oversight of children. In the end, the sale went ahead despite Parliament's opposition.

End of the Duchy

editWhen the Austro-Prussian War broke out on 14 June 1866, the Duchy of Nassau took the side of Austria. The war was won at the Battle of Königgrätz on 3 July and the "victory" of Nassau over Prussia at the Battle of Zorn near Wiesbaden on 12 July 1866 did nothing to prevent the annexation of Nassau by Prussia. Nassau become the Wiesbaden Region into the Province of Hesse-Nassau.[citation needed]

Before the conclusion of the Prague Peace on 23 August 1866 and two days before the creation of the North German Confederation, on 16 August 1866, the king announced to both houses of the Landtag of Prussia that Prussia would annex Hannover, Hesse-Kassel, the city of Frankfurt, and Nassau. Both houses were asked to give their assent to a law bringing the Prussian constitution into force in those territories on 1 October 1867.[3] The law was passed by both houses of the Prussian Landtag on 20 September 1866 and was published in the gazette. The next step was the publication of the notice of annexation, which made the citizens of the nine annexed regions into citizens of Prussia. After these official actions, further practical actions were taken to bring the annexed regions into full union with the rest of Prussia.[4]

Duke Adolphe, the last Duke of Nassau, received 15,000,000 guilders as compensation, as well as Biebrich Palace, Schloss Weilburg, Jagdschloss Platte and Luxemburgisches Schloss in Königstein. He became Grand Duke of Luxembourg in 1890 after the male line of Orange-Nassau became extinct.[5]

In 1868, Nassau, along with Frankfurt and the Electorate of Hesse were united in the new Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau. The capital of the new province was Kassel, which had previously been the capital of the Electorate of Hesse. Nassau and Frankfurt became the administrative region of Wiesbaden. In 1945, the majority of the old Duchy of Nassau fell within the American occupation zone and became part of the state of Hesse. Wiesbaden remained an administrative region within Hesse until 1968, when it was incorporated into Darmstadt. A small part of the Duchy of Nassau fell within the French occupation zone and became the administrative region of Montabaur in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate. In 1956, a referendum on joining the state of Hesse was rejected by voters.[6]

-

West side of a boundary stone, inscribed with ON for Orange-Nassau

-

East side of a boundary stone, inscribed with HD for Hesse-Darmstadt

-

Boundary stone of the Duchy of Nassau and the Kingdom of Prussia

-

Boundary column of the Duchy of Nassau in Dillenburg

Politics

editForeign affairs

editIn foreign affairs, the Duchy's geographic location and economic weakness greatly limited its room to manoeuvre – in the Napoleonic period, it had no autonomy at all. The Nassau 'army' was at the beck and call of Napoleon. In 1806, they were stationed as occupation troops in Berlin. Then three battalions were stationed at the Siege of Kolberg. Two regiments of infantry and two cavalry squadrons fought for more than five years in the Peninsular war; only half of them came back. In November 1813, Nassau joined the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon. Nassau troops fought at the battle of Waterloo: 1/2 rgt. was part of the crew of the fortified Hougemont farm which hold out against Napoleon, 1/1 rgt. was heavily battered after the French taking of La Haye Sainte. Of 7507 men inc. volunteers, 887 were killed in action. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Nassau was a member of the German Confederation.

Military

editNassau's military policy was shaped by Duchy's membership of the German Confederation. Like the rest of the administration, the military was reformed in order to unite the various military forces inherited from Nassau's predecessor states into a single body.

The majority of the troops consisted of two regiments of infantry, created in 1808/09. During the Napoleonic Wars, these were supported by squadrons of Jäger. After the Battle of Waterloo, the Duchy raised an artillery company, which became an artillery division with two companies in it after 1833. Further units were added (pioneers, Jägers, baggage trains, reserves). Further contingents were added as required during wartime. The whole military was placed under a brigade command structure. At its head was the Duke, but day-to-day operations were organised by an Adjutant general. Ordinarily, the Nassau army contained roughly 4,000 soldiers.

After the annexation of the Duchy, most of the officers and soldiers joined the Prussian Army.

Education

editThe Duchy could not afford its own university, so Duke William I made a treaty with the Kingdom of Hannover, which allowed citizens of Nassau to study at the University of Göttingen. In order to finance schools and university scholarships, on 29 March 1817, Duke William established the Nassau Central Study Fund, which still exists today, by consolidating a number of older secular and religious funds, and endowed it with farmland, forests, and bonds.

In Göttingen, non-Nassau students occasionally participated illicitly in a free dinner funded by the Central Study Fund. The German term nassauer, meaning 'someone who partakes of a privilege they are not entitled to' is said to derive from this practice, although etymologists report that the word is actually a Berlin dialect term derived from Rotwelsch Yiddish and that this story was invented after the fact.

Religion

editAs a result of the disparate territories that were joined together to form the Duchy, Nassau was not a religiously unified state. In 1820, the breakdown of religious groups was: 53% United Protestant, 45% Catholic, 1.7% Jewish, and 0.06% Mennonite. However, settlements with more than one religion were unusual. Most villages and cities were clearly dominated by the members of one of the two major Christian groups. As was common in Protestant parts of Germany, the constitution placed the church under state control. The Lutheran and Reformed churches agreed to unite into the single Protestant Church in Nassau in 1817, at the Unionskirche in Idstein, making it the first united Protestant church in the German Confederation.

Even in 1804 there was an effort to establish a Catholic diocese of Nassau, but it was only in 1821 that the Duchy of Nassau and the Holy See came to an agreement on the establishment of the diocese of Limburg, which was formally established in 1827.

Alongside the actual church policy, there were other points of interaction between state politics and ecclesiastical matters. The relocation of a religious society, the order of the Redemptorists, to Bornhofen led to conflict between the state and the Bishop. The Redemptorists stayed in Bornhofen. The Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ, founded in Dernbach were another religious society, which soon took charge of care for the sick within the diocese. After some initial problems at lower levels, they were tolerated by the government of the Duchy and even tacitly supported, because they had received enthusiastic commendation by doctors. In many places 'hospitals' or mobile medical stations were established, the fore-runners of modern Sozialstationen.

Dukes

edit| Duke | Image | Birth | Death | Reign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frederick Augustus | 23 April 1738 | 24 March 1816 | 30 August 1806 – 24 March 1816 | |

| William | 14 June 1792 | 20 August 1839 | 24 March 1816 – 20 August 1839 | |

| Adolphe | 24 July 1817 | 17 November 1905 | 20 August 1839 – 20 September 1866 |

The Dukes of Nassau derived from the Walram line of the House of Nassau. Members of the Walram line of the House of Nassau still reign in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (Nassau-Weilburg). The reigning Grand Duke still uses Duke of Nassau as a courtesy title.

The royal family of the Netherlands derives from the Ottonian line of Orange-Nassau, which split from the Walramian line in 1255.

Chief ministers

edit| Chief minister | Image | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hans Christoph Ernst von Gagern | 1806 | 1811 | |

| Ernst Franz Ludwig Marschall von Bieberstein | 1806 | 1834 | |

| Carl Wilderich von Walderdorff | 1834 | 1842 | |

| Friedrich Anton Georg Karl von Bock und Hermsdorf | 1842 | 1843 | |

| Emil August von Dungern | 1843 | 1848 | |

| August Hergenhahn | 1848 | 1849 | |

| Friedrich von Wintzingerode | 1849 | 1852 | |

| Prince August Ludwig zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg | 1852 | 1866 | |

| August Hergenhahn | 1866 | 1866 |

Economy

editThe economic situation of the small Duchy was precarious. The majority of the land area of the country was Mittelgebirge, which had little agricultural value and represented a substantial barrier to internal transport. Even so, more than a third of the population worked on their own farmland, which was broken up into small areas as a result of partible inheritance. This smallholdings generally had to supplement their income from other sources – often in the Westerwald, this was by service as a peddler. Among tradesmen, the overwhelming majority were artisans.

Currency

editThe Duchy belonged the south German currency area. The most important denomination was therefore the guilder. This was minted for use as currency money. Up to 1837, there were 24 guilders to the Cologne silver marks (233.856 grammes). The guilder was divided into 60 kreutzer. Small change was minted in silver and copper, at 6, 3, 1, 0.5, and 0.25 grammes.[7]

From 1816, there were also Kronenthaler of 162 kreutzer (i.e. 2.7 guilders). Between 1816 and 1828, the mint of the Duchy was located in buildings in Limburg, which are now the Bishop's curia. From 1837, the Duchy was one of the members of the Munich Currency Treaty, which set the silver mark (233.855 g) at 24.5 guilders. After the conclusion of the Dresden Coinage Convention in 1838, the Thaler was also legal tender and was minted in small quantities. Two dollars were equivalent to 3.5 guilders. In 1842, the Heller, valued at a quarter of a kreutzer, was introduced as the smallest denomination. After the Vienna Currency Treaty of 1857, the Duchy also minted the Vereinsthaler. A Pfund (500 g) of silver was equivalent to 52.5 guilder or 30 taler. The Heller was replaced by the Pfennige, also worth a quarter of a Kreutzer.

Banknotes, known as Landes-Credit-Casse-Scheine were produced at Wiesbaden by the Landes-Credit-Casse from 1840. They had a face value of one, five, ten, and twenty-five guilders.

References

edit- ^ Grand Duchess Charlotte abdicated in 1964, but she died in 1985

- ^ Clotilde Countess of Nassau-Merenberg is the last patrilineal descendant of the House of Nassau though she descends from a family considered to be non-dynastic

- ^ Provinzial-Correspondenz vom 12. September 1866: Die Erweiterung des preußischen Staatsgebietes zitiert nach Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: Amtspresse Preußens.

- ^ Provinzial-Correspondenz vom 26. September 1866: Die neuerworbenen Länder zitiert nach Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: Amtspresse Preußens.

- ^ "Image Gallery of the Coins of Nassau". Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Brigitte Meier-Hussing: "Das Volksbegehren von 1956 zur Rückgliederung des Regierungsbezirk Montabaur/Rheinland-Pfalz nach Hessen." Verein für Nassauische Altertumskunde, Nassauische Annalen, Volume 111, Wiesbaden 2000, ISSN 0077-2887.

- ^ Otto Satorius: Nassauische Kunst- und Gewerbeausstellung in Wiesbaden 1863; Seite: 43; Wiesbaden 1863.

Bibliography

edit- Herzogtum Nassau 1806–1866. Politik – Wirtschaft – Kultur. Wiesbaden: Historische Kommission für Nassau. 1981. ISBN 3-922244-46-7.

- Bernd von Egidy (1971). "Die Wahlen im Herzogtum Nassau 1848–1852". Nassauische Annalen. 82. Wiesbaden: 215–306.

- Konrad Fuchs (1968). "Die Bergwerks- und Hüttenproduktion im Herzogtum Nassau". Nassauische Annalen. 79. Wiesbaden: 368–376.

- Königliche Regierung zu Wiesbaden (1876–1882). Statistische Beschreibung des Regierungs-Bezirks Wiesbaden. Wiesbaden: Verlag Limbart.

- Michael Hollman: Nassaus Beitrag für das heutige Hessen. 2nd edition. Wiesbaden 1994.

- Otto Renkhoff (1992). Nassauische Biographie. Kurzbiographien aus 13 Jahrhunderten (2 ed.). Wiesbaden: Historische Kommission für Nassau. ISBN 3-922244-90-4.

- Klaus Schatz (1983). "Geschichte des Bistums Limburg". Quellen und Abhandlungen zur mittelrheinischen Kirchengeschichte. 48. Wiesbaden.

- Winfried Schüler (2006). Das Herzogtum Nassau 1806–1866. Deutsche Geschichte im Kleinformat. Wiesbaden: Historische Kommission für Nassau. ISBN 3-930221-16-0.

- Winfried Schüler (1980). "Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im Herzogtum Nassau". Nassauische Annalen. 91. Wiesbaden: 131–144.

- Christian Spielmann (1909). Geschichte von Nassau: Vol. 1. Teil: Politische Geschichte. Wiesbaden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Christian Spielmann (1926). Geschichte von Nassau: Vol. 2. Teil: Kultur und Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Montabaur.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Franz-Josef Sehr (2011). "Die Gründung des Nassauischen Feuerwehrverbandes". Jahrbuch für den Kreis Limburg-Weilburg 2012. Limburg-Weilburg: Der Kreisausschuss des Landkreises Limburg-Weilburg: 65–67. ISBN 978-3-927006-48-5.

- Stefan Wöhrl (1994). Forstorganisation und Forstverwaltung in Nassau von 1803 bis 1866. Wiesbaden: Georg-Ludwig-Hartig-Stiftung.