Doux commerce (lit. sweet commerce) is a concept originating from the Age of Enlightenment stating that commerce tends to civilize people, making them less likely to resort to violent or irrational behaviors.[1][2][3][4] This theory has also been referred to as commercial republicanism.[5]

Origin and meaning

editProponents of the doux commerce theory argued that the spread of trade and commerce will decrease violence, including open warfare.[6][7] Montesquieu wrote, for example, that "wherever the ways of man are gentle, there is commerce; and wherever there is commerce, there the ways of men are gentle"[8] and "The natural effect of commerce is to lead to peace".[1] Thomas Paine argued that "If commerce were permitted to act to the universal extent it is capable, it would extirpate the system of war".[1] Engaging in trade has been described as "civilizing" people, which has been related to virtues such as being "reasonable and prudent; less given to political and, especially, religious enthusiasm; more reliable, honest, thrifty, and industrious".[1] In the greater scheme of things, trade was seen as responsible for ensuring stability, tolerance, reciprocity and fairness.[1]

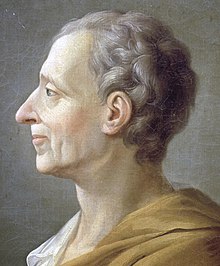

It is not clear when this term was coined. Writings of Jacques Savary, a 17th-century French merchant, have been suggested as one possible origin[8] but similar use has been traced earlier, for example to a Renaissance-era 16th century work by Michel de Montaigne.[9] The basic idea that trade lessens the chance for conflict between nations can be traced as far as writings of Ancient Greece.[10] It became popular in the 17th century writings of some scholars from the Age of Enlightenment, and has been endorsed by thinkers like Montesquieu, Voltaire, Smith, and Hume, as well as Immanuel Kant.[1][11][12] It has been discussed in their essays and literary works; for example Voltaire's poem Le Mondain (1736) has been described as endorsing the doux commerce theory.[11] Out of those, Montesquieu has been argued to be the writer most responsible for the spread of this idea in his influential Spirit of Law (1748),[13][14] and the theory is sometimes described as "Montesquieu's doux commerce." (although Montesquieu did not use the term itself).[15][16][17]

In modern scholarship, the term has been analyzed by the German economist Albert Hirschman in his 1977 work The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments For Capitalism Before Its Triumph. Hirschman is credited with summarizing the doux commerce argument for the modern readers and popularizing the term in modern discourse.[9][8][18][19]

Critique

editAt the same time, even Montesquieu and other proponents of trade from the Enlightenment era have cautioned that some social effects of commerce may be negative, for example commodification, conspicuous consumption, or erosion of interest in non-commercial affairs.[1] Edmund Burke offered the following critique of the doux commerce idea: that it is not commerce that civilizes humans, it is that humans are civilized through culture, which enables them to engage in commerce.[1]

This theory led to trade becoming associated with peaceful and inoffensive activities representative of the "civilized" West European nations; which has however been criticized by later scholars as omitting the facts that much of the said "gentle" trade and resulting prosperity was built on activities like the slave trade and colonial exploitation.[8][7]

The doux commerce theory continues to be debated in the modern times. The question of whether commerce's impact on the society is net positive or net negative has no conclusive answer. Mark Movsesian noted that "as Hirschman once suggested, the doux commerce thesis is right and wrong at the same time: the market both promotes and corrupts good morals."[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Movsesian, Mark (10 January 2018). "Markets and Morals: The Limits of Doux Commerce". William and Mary Business Law Review. 9 (2). Rochester, NY: 449–475. SSRN 3099712.

- ^ Boettke, Peter J.; Smith, Daniel J. (2014). "The Theory of Social Cooperation Historically Contemplated". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2173338.

- ^ Schilpzand, Annemiek; de Jong, Eelke (2023). "Do market societies undermine civic morality? An empirical investigation into market societies and civic morality across the globe". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 208: 39–60. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2023.01.020.

- ^ Harris, Colin; Myers, Andrew; Kaiser, Adam (2023). "The humanizing effect of market interaction". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 205: 489–507. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2022.11.028.

- ^ Margaret Schabas; Carl Wennerlind (2008). David Hume's Political Economy. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-134-36250-9.

- ^ Kenneth Pomeranz; Steven Topik (1999). The World that Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400-the Present. M.E. Sharpe. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-7656-2849-7.

- ^ a b Manu Saadia (31 May 2016). Trekonomics: The Economics of Star Trek. Inkshares. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-1-941758-76-2.

- ^ a b c d Andrea Maneschi (1 January 1998). Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78195-624-3.

- ^ a b Anoush Fraser Terjanian (2013). Commerce and Its Discontents in Eighteenth-Century French Political Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–14. ISBN 978-1-107-00564-8.

- ^ Francesca Trivellato; Leor Halevi; Catia Antunes (20 August 2014). Religion and Trade: Cross-Cultural Exchanges in World History, 1000–1900. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-937921-7.

- ^ a b Graeme Garrard (9 January 2003). Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment: A Republican Critique of the Philosophes. SUNY Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7914-5604-0.

- ^ Katrin Flikschuh; Lea Ypi (20 November 2014). Kant and Colonialism: Historical and Critical Perspectives. OUP Oxford. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-19-103411-4.

- ^ Andrew Scott Bibby (29 April 2016). Montesquieu's Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-137-47722-4.

- ^ Brian Singer (31 January 2013). Montesquieu and the Discovery of the Social. Springer. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-137-02770-2.

- ^ Francesca Trivellato (12 February 2019). The Promise and Peril of Credit: What a Forgotten Legend about Jews and Finance Tells Us about the Making of European Commercial Society. Princeton University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-691-17859-2.

- ^ Sharon A. Stanley (19 March 2012). The French Enlightenment and the Emergence of Modern Cynicism. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-107-01464-0.

- ^ Sankar Muthu (17 September 2012). Empire and Modern Political Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-83942-6.

- ^ Christopher K. Clague; Shoshana Grossbard-Shechtman; American Academy of Political and Social Science (1 January 2001). Culture and development: international perspectives. Sage Publications. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7619-2393-0.

Hirschman (1977, 1982) reviews the history of an idea he dubs the "doux-commerce thesis."

- ^ Dickey, Laurence (1 January 2001). "Doux-commerce and humanitarian values: Free Trade, Sociability and Universal Benevolence in Eighteenth-Century Thinking". Grotiana. 22 (1): 271–317. doi:10.1163/016738312X13397477910549. ISSN 0167-3831.