Douglas Granville Chandor (20 August 1897 – 13 January 1953) was a British-born American painter of portraits, of which he created more than 200.

Douglas Chandor | |

|---|---|

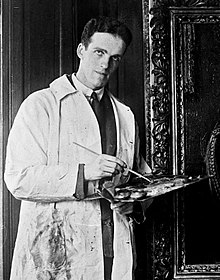

Chandor in 1921 | |

| Born | Douglas Granville Chandor 20 August 1897 Warlingham, Surrey, England |

| Died | 13 January 1953 (aged 55) Weatherford, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Portrait painter and garden designer |

| Spouses | Pamela Trelawny

(m. 1920; div. 1932)Ina Kuteman Hill (m. 1934) |

| Children | 1 |

| Father | John Arthur Chandor |

| Relatives |

|

His early paintings included two of the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII). In 1923, he was commissioned to paint the British Empire Prime Ministers During the Imperial Conference at 10 Downing Street. He later painted Winston Churchill and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and did a sketch of the "Big Three at Yalta", although the painting never happened. His 1952 portrait of Elizabeth II is in the British Government Art Collection, and is the first painted portrait for which she sat following her accession. His other portraits include Sara Delano Roosevelt, U.S. president Herbert Hoover, and U.S. financier and statesman Bernard Baruch.

He designed Chandor Gardens in Weatherford, Texas, which are a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark.

Early life

editDouglas Chandor was born in Warlingham, Surrey, England, on 20 August 1897.[1] He was baptised on 19 October in Emmanuel Church, South Croydon, where at the time his family lived at Normanton Road.[2] His father was John Arthur Chandor and his mother was Lucy May Chandor (née Newton).[3] His half-sister Paquita Louise de Shishmareff (born Louise A. Chandor, 1882–1970), the daughter of John Arthur Chandor and Elizabeth (Red) Fry Ralston, was an American antisemitic, pro-fascist author under the pen name Leslie Fry.[4] According to the Daily Mail in 1921, he was also a nephew of duelist Count Chandos (a misspelling - should be Count Chandor), who was a friend of Napoleon III.[5][6]

Chandor was educated at Radley College from 1910 to 1914, and after leaving immediately enlisted in the British Army's 1st Life Guards, before later transferring to the Lovat Scouts.[3][7] He was discharged after contracting typhoid and suffering severe knee damage.[8] He trained at London's Slade School of Fine Art, specialising in portraiture.[3] By 1919 he was a portrait painter.[9]

Career

editWithin two years of starting at the Slade, Chandor had held his first one-man exhibition.[7]

His first important commission was Sir Edward Marshall-Hall in 1919, which was shown at the Royal Academy and led to another to paint the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) in 1921.[3] Two portraits of the Prince where ultimately completed and displayed at Gieves, Old Bond Street.[10][11] The Sunday Post reported that one was very much like him and the other could have been of anyone else.[10]

In 1923, he was commissioned to paint the British Empire Prime Ministers During the Imperial Conference at 10 Downing Street.[3] The prime ministers were shown life-size around a table, and included Stanley Bruce (Australia), Stanley Baldwin (United Kingdom), and William Lyon Mackenzie King (Canada) seated.[12] Standing from left to right were William Massey (New Zealand), Jai Singh Prabhakar (Alwar), Tej Bahadur Sapru (India), W. T. Cosgrave (Ireland), W. R. Warren (Newfoundland), and General Smuts (South Africa).[12] It was on display on the staircase going up to the State Apartments at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.[3][13]

Chandor painted Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill.[9] He did a sketch of the "Big Three at Yalta", and although he painted Churchill and Roosevelt, he never painted Joseph Stalin, so the painting never happened.[14] According to Chandor, Roosevelt had commissioned the project, which he and Churchill both sat for.[9][15] However, Stalin said he was too busy and offered to send Chandor a photograph to work on, but Chandor felt that unacceptable.[9]

His 1952 portrait of Elizabeth II is in the British Government Art Collection.[16] It was the first painted portrait of her following her accession and commissioned by Eleanor Roosevelt.[9] Chandor travelled to London specifically to paint her[17] and was reported to have said that "she could not have made a better subject".[9] According to Chandor, the Queen was an ideal model "standing for me as long as I wished with soldierly self-discipline and sitting as well as a sphinx when I worked on the face".[18] In the painting, she wears the ribbon and star of the Order of the Garter.[18] It took eight hour-long sittings in Buckingham Palace's drawing room, during which Chandor was accompanied by his wife, and the two of them kept the Queen amused with jokes and poems. The Queen was able to follow Chandor's work through a mirror placed behind him.[18] Chandor told Life magazine that "the queen is an infinitely more beautiful woman than any photograph has ever shown, and when she smiles there is a radiance such as I have seldom seen in any face."[18] The portrait was placed on public exhibition in New York City in May through June 1953.[19] Eleanor Roosevelt saw the painting at the Wildenstein Galleries before it went on to hang in the British embassy in Washington, D.C., and thought it "one of his real masterpieces".[20]

About 200 paintings by Chandor have been recorded, including Sara Delano Roosevelt, U.S. president Herbert Hoover,[7] and U.S. financier and statesman Bernard Baruch.[21] Earlier portraits include Princess Ghika and Lady Alexandra Metcalfe.[5]

In 1966, The Illustrated London News pointed out that the painting to the left of the fireplace in the drawing room at Chartwell was a Chandor portrait of Lady Churchill.[22]

Personal life

editIn 1920, Chandor married Pamela Dorothy May Trelawny (1896–1971).[3] They had a daughter, Jill Evelyn Trelawny Chandor (1921–1961), who married Lt-Col. Stanley Dexter Peirce (1910–1976), and divorced in 1932.[3] In 1934, he married Ina Kuteman Hill (1890–1978) of Weatherford, Texas.[3]

In 1936, they built a house on cow pasture land owned by her family in Weatherford, and established a 3.5-acre (1.4-hectare) garden, White Shadows.[23] The house was designed by the architect Joseph Pelich, mostly as a studio, as Chandor spent half the year there and half at his studio in New York City.[7] The house was expanded in the 1940s and again in the 1960s.[7]

He developed pneumonia in October 1952 while painting the Queen, and was treated by her physician Sir Daniel Davies.[9] Chandor died on 13 January 1953 in Weatherford.[9] The gardens were renamed Chandor Gardens, and kept open to the public until his wife's death in 1978.[23] They were neglected until 1994, when Melody and Chuck Bradford bought them and spent a year cleaning and repairing the gardens and Chandor's house and studio, and began hosting weddings and garden tours.[23] In 2002, the City of Weatherford acquired Chandor Gardens.[23] The house and gardens are a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark.[7]

Douglas and Ina Chandor are buried in Weatherford's Old City Greenwood Cemetery.[7]

References

edit- ^ "Kent, Folkestone". 1911 England Census. 1911. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022 – via ancestry.co.uk.

- ^ "South Croydon, Emmanuel baptisms". Surrey, England, Church of England Baptisms, 1813-1917. 1897. Retrieved 9 September 2022 – via ancestry.co.uk.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Minor, David. "Chandor, Douglas Granvil (1897–1953)". Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Hagemeister, Michael (2022). The perennial conspiracy theory : reflections on the history of the Protocols of the elders of Zion. Abingdon, Oxon. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9781032060156. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "A romantic career". Daily Mail. 19 March 1921. p. 1. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ The article titled A romantic career in the Daily Mail (issue of 19 March 1921, p. 1) misspelled Douglas' relative's name as Count "Chandos". The correct spelling of the name is Count "Chandor". This friend of Napoleon III has been correctly identified as Count Móric (Moritz) Sándor de Szlavnicza (May 23, 1805 - February 23, 1878), a famous Hungarian horseman and duelist. Douglas Chandor's father John Arthur Chandor (1850-1909) claimed that his own father (Douglas' paternal grandfather) Lasslo Philip Chandor (orig.: László Fülöp Sándor) (1815-1894) was a Count and a member of the same noble Sándor de Szlavnicza family from which Count Móric was descended. However, researchers have carefully examined all the standard Hungarian genealogical and historical sources and records relevant to this issue, and to date no evidence has been found that Lasslo Philip Chandor was a member of the noble Hungarian Sándor de Szlavnicza family. Therefore, the idea that Lasslo Philip Chandor was a Count, and that he was descended from the noble Hungarian Sándor de Szlavnicza family, appear to be falsehoods fabricated by John Arthur Chandor (who occasionally also referred to himself as "Count Chandor"), mainly for the purpose of attempting to enhance his own social standing in countries where he frequently resided, which included the United States, England, France, and Russia. On this point see the booklet titled Concerning the Man John Arthur Chandor, Alias Count Chandor, Alias Captain Chandor, Alias Montagu Chandor, Alias Captain Carlton, & c (London?: Private Vigilance Society, [189-]) (44 pages), which can be read online for free at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.a0008989626&view=1up&seq=5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Douglas the Artist". City of Weatherford. Archived from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Powers, John E.; Powers, Deborah Daniels (2000). Texas Painters, Sculptors & Graphic Artists: A Biographical Dictionary of Artists in Texas Before 1942. Woodmont Books. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-9669622-0-8. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "He painted portrait of the Queen". Somerset Guardian and Radstock Observer. 16 January 1953. p. 3. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "One faithful likeness". Sunday Post. 1 January 1922. p. 10. Retrieved 8 September 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Holland, G. A.; Roberts, Violet M. (1937). History of Parker County: And, The Double Log Cabin. Herald Publishing Company. p. 199. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ a b "An Empire picture in an Empire Exhibition". The Sphere. 31 May 1924. p. 6. Retrieved 10 September 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Town and country notes". Northampton Mercury. 21 September 1928. Retrieved 10 September 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Harold & Elizabeth Lawrence – Framed Photo of Douglas Chandor's Sketch "Big Three at Yalta"". Chandor Gardens Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Franklin D. Roosevelt". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Douglas Granville Chandor 1897–1953". Art UK. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ "Royal Society Of Portrait Painters Exhibition". Superstock. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Speaking of pictures: Painter of famous people portrays the new queen". Life. Vol. 33, no. 16. 20 October 1952. pp. 12–13. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Chandor Portrait of Queen is Put on View". The New York Times. 19 May 1953. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Roosevelt, Eleanor (23 May 1953). "May 23, 1953". Eleanor Roosevelt's diary. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Bernard Mannes Baruch". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Chartwell". Illustrated London News. 25 June 1966. p. 22. Retrieved 5 September 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d "History of Chandor Gardens". Chandor Gardens Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.