Owen Joseph "Donie" Bush (/doʊniː/; October 8, 1887[1] – March 28, 1972) was an American professional baseball player, manager, team owner, and scout. He was active in professional baseball from 1905 until his death in 1972.

| Donie Bush | |

|---|---|

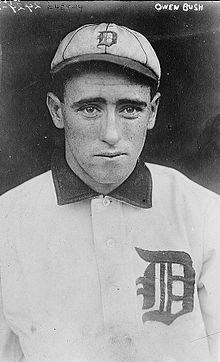

Bush in 1910 with the Detroit Tigers | |

| Shortstop / Manager | |

| Born: October 8, 1887 Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. | |

| Died: March 28, 1972 (aged 84) Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. | |

Batted: Switch Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 18, 1908, for the Detroit Tigers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 15, 1923, for the Washington Senators | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .250 |

| Home runs | 9 |

| Runs batted in | 436 |

| Stolen bases | 404 |

| Managerial record | 497–539 |

| Winning % | .480 |

| Teams | |

| As player

As manager | |

Bush was the starting shortstop for the Detroit Tigers from 1908 to 1921 and an infielder for the Washington Senators from 1921 to 1923. He was recognized as one of the best defensive shortstops of the dead-ball era. He had more putouts, assists, and total chances than any other shortstop of the era, and his 1914 totals of 425 putouts and 969 chances are still American League records for shortstops (and the major league record for putouts). He also led the American League in assists by a shortstop on five occasions and holds the major league record with nine triple plays.

As a batter, Bush did not hit for a high batting average but was regularly among the major league leaders in drawing bases on balls, sacrifice hits, stolen bases, and runs scored. At the time of his retirement in 1923, Bush's 1,158 bases on balls ranked second in major league history. His 337 sacrifice hits still ranks fifth in major league history, and his 1909 total of 52 sacrifice hits is the fourth highest in major league history. He ranked among the American League leaders in stolen bases ten times, and, during the decade from 1910 to 1919, the only players to score more runs than Bush were Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, and Tris Speaker. Bush's 400 stolen bases as a Tiger rank second in franchise history, behind only Cobb.

Bush also served as a manager in professional baseball for the Washington Senators (1923), Indianapolis Indians (1924–1926, 1943–1944), Pittsburgh Pirates (1927–1929), Chicago White Sox (1930–1931), Cincinnati Reds (1933), Minneapolis Millers (1932, 1934–1938), and Louisville Colonels (1939). His 1927 Pittsburgh Pirates won the National League pennant and lost to the 1927 Yankees in the World Series. Bush was also a co-owner of the Louisville Colonels (1938–1940) and Indianapolis Indians (1941–1952), president of the Indians (1941–1952, 1956–1969), and a scout for the Boston Red Sox (1953–1955). He was given the title "King of Baseball" during Major League Baseball's 1963 winter meetings. He was known as "Mr. Baseball" in Indianapolis and was an inaugural inductee of the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame.

Early years

editBush was born in 1887 in Indianapolis, Indiana.[2] He was the son of Irish-American parents and raised on the east side of Indianapolis. His father died when Bush was a child,[3] and at the time of the 1900 United States Census, Bush was living with his mother and two older siblings in Center Township, near or in Indianapolis.[4][5][6][7]

Playing career

editCareer overview

editBush was one of the best defensive shortstops of the dead-ball era.[citation needed] He collected more putouts, assists, and total chances than any other shortstop of the era, and his 1914 total of 425 putouts is still the Major League record for shortstops.[8] His 1914 total of 969 chances is also still the American League record.[9] He also led the American League in assists by a shortstop on five occasions: 1909 (567), 1911 (556), 1912 (547), 1914 (544), and 1915 (504).[2] Bush also holds the Major League record (shared with Bid McPhee) for most career triple plays with nine. Bush's triple plays came on May 4, 1910, April 24, 1911, May 20, 1911, September 9, 1911, April 6, 1912, August 23, 1917, August 14, 1919, May 18, 1921, and September 14, 1921.[10]

As a batter, Bush ranked among the American League leaders in bases on balls 12 straight years, from 1909 through 1920, and led the league five times. His career high was 118 bases on balls in 1915. During the decade from 1910 to 1919, no Major League player had more bases on balls than Bush. At the time of his retirement in 1923, Bush had 1,158 walks, second best in Major League history trailing only Eddie Collins.[11]

Bush also collected 337 sacrifice hits in his career, ranking him fifth on the all-time Major League leader list (behind Hall of Famers Eddie Collins and Willie Keeler). He led the league with 52 sacrifice hits in 1909 (fourth highest single season total in Major League history) and hit another 48 (seventh highest single season total in Major League history) in 1920.[12]

In 1920, Baseball Magazine rated Bush among the top ten players in Major League Baseball over the past decade in the categories of "waiters" (1st with an average of 88.4 bases on balls per year), "run-getters" (4th with an average of 90 runs per year), and "base-stealers" (7th with an average of 30.4 stolen bases per year).[13]

Bush was also one of the shortest players in the Major Leagues at five feet, six inches (1.7 meters) and weighed between 130 and 140 pounds.[2][14] Bush once said, "I used to tell 'em it ain't how big you are, it's how good you are. But whenever another team had an uncommonly small player, I'd slip up and compare heights. Always turned out he was an inch taller than me."[14]

Bush's nickname, "Donie", was reportedly bestowed on him as a result of a comment by Detroit teammate Ed Killian in 1909. Bush explained, "One day after I had struck out, I asked Eddie Killian what kind of ball I swung at and missed. Killian said it was a donie ball. I never learned what a donie ball was, but the Tigers started calling me Donie and the name just stuck."[15]

- Career statistics

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | TB | SH | HBP |

| 1946 | 7210 | 1280 | 1804 | 186 | 74 | 9 | 436 | 404 | 75 | 1158 | 346 | .250 | .356 | .300 | 2165 | 337 | 29 |

Minor leagues

editBush began his professional baseball career in 1905 playing for the Sault Ste. Marie Soos in the Copper Country Soo League.[16] In 1906, he played portions of the season for the Zanesville Moguls in the Ohio–Pennsylvania League and the Saginaw Wa-was of the Southern Michigan League.[16] In early August 1906, he was acquired by the Dayton Veterans of the Central League.[17] He appeared in 58 games for Dayton, compiling a .158 batting average with 98 putouts and 156 assists.[18]

South Bend Greens

editIn 1907, he played for the South Bend Greens in the Central League.[19] He appeared in 127 games, compiling a .279 batting average with nine doubles and seven triples.[16] Baseball Magazine noted that, while playing in South Bend, Bush earned "the reputation of being the fastest, best all-around shortstop the Central League had ever seen."[20]

Indianapolis Browns

editAt the end of the 1907 season, after a good showing in South Bend, Bush was drafted by the Chicago White Sox, Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers, and was awarded to the Tigers. He was sold by the Detroit team to play the 1908 season for the Indianapolis Browns of the American Association.[19][20] He appeared in 153 games for Indianapolis and was the team's starting shortstop with 330 putouts, 472 assists, 54 errors, 856 total chances, and a .937 fielding percentage. As a batter, he had 28 stolen bases, 18 sacrifice hits, seven triples, and a .247 batting average.[21] He helped Indianapolis win the American Association pennant for 1908,[22] and at the end of the 1908 season, The Sporting Life wrote that Bush was "generally credited with being the best ball player outside the big leagues during the season in the minors which has just closed.[23]

Detroit Tigers

edit1908 season

editIn late August 1908, Bush, then known as "Ownie", was sold by the Indianapolis club to the Detroit Tigers.[24] He joined the Tigers in mid-September after Detroit's starting shortstop, Charley O'Leary, had been injured. Bush replaced O'Leary at shortstop for the team's final 20 regular season games.[2][15][23] Bush's performance in the final weeks of the season, during a tight pennant race, was credited with having "thrust the panting Tigers first over the line."[20] Because Bush had not been with the Tigers for more than 30 days, he was ineligible to play in the 1908 World Series.[19] At the end of the 1908 season, Baseball Magazine wrote:

This diminutive and youthful shortstop came to the rescue of the Detroit club and made it possible for them to win the American League pennant. . . . He helped to win the American Association pennant for the Hoosiers by his wonderful all around work, and then came on to Detroit in time to save Jennings' team from defeat. He is about as fast as Cobb on the bases, a great fielding shortstop and a good batsman, a man who hits right or left handed with equal efficiency.[19]

1909 season

editIn January 1909, Bush signed a contract to return to the Tigers,[25] and he became the Tigers' starting shortstop for the next 13 seasons. He compiled a .273 batting average and a .380 on-base percentage in 1909 and led the American League with 676 plate appearances, 88 bases on balls, and 52 sacrifice hits.[2] His 52 sacrifice hits remains the fourth highest single season total in major league history,[12] and his .380 on-base percentage was the third highest in the American League in 1909 behind teammate Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins. His 114 runs scored was second in the league behind only Cobb.[2] Bush's 52 stolen bases also set an American League rookie record that stood for 83 years until Kenny Lofton stole 66 bases in 1992.[10]

Bush also played in all seven games of the 1909 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, becoming the surprise hitting star for Detroit. With Detroit stars Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford slumping in the World Series (batting .231 and .250 respectively), Bush hit .318 with an on-base percentage of .483. He also scored five runs, collected five bases on balls, was twice hit by a pitch, and compiled nine putouts, 18 assists, and three double plays (but also committed five errors).[2]

1910 and 1911 seasons

editAfter a brief holdout in the spring of 1910, Bush re-signed with the Tigers in mid-March.[26][27] During the 1910 and 1911 seasons, Bush led the American League in bases on balls for the second and third consecutive seasons. His total of 49 stolen bases ranked third in the American League in 1910, and his 126 runs scored in 1911 ranked second in the league. Defensively, Bush's 1910 fielding percentage of .940 led American League shortstops, and his 1910 defensive Wins Above Replacement (WAR) rating of 2.0 ranked third among all American League players, regardless of position. In 1911, he led the American League's shortstops with 372 putouts, 556 assists, and 75 errors. His range factor of 6.19 in 1911 was a career-high and the second best among American League shortstops.[2] In the voting for the 1911 Chalmers Award (the predecessor of the American League Most Valuable Player award), Bush finished in 14th place, as teammate Ty Cobb won the award.[28]

1912 season

editIn 1912, Bush led the major leagues with 117 bases on balls.[2] The Sporting Life noted: "Bush is one of the hardest men in the game to pitch to. He is so small that a pitcher has to have absolute control to get the ball over for him, and it makes him a most valuable lead-off man for a team, because there is hardly a day that he does not reach the bases one or more times."[29] During the 1912 season, Bush also led all American League players (regardless of position) with 547 assists, and his 6.00 range factor was the highest among American League shortstops. He also ranked among the American League leaders with a defensive WAR of 1.8 (4th among players at all positions), 107 runs scored (7th), 37 stolen bases (8th), 317 putouts at shortstop (4th), a .929 fielding percentage (2nd among shortstops), and 66 errors (2nd).[2]

1913 season

editIn 1913, Bush led the American League with 694 plate appearances and was again among the league leaders with 80 bases on balls (3rd), 44 stolen bases (6th), 98 runs (8th), 331 putouts at shortstop (2nd), and 510 assists at shortstop (2nd).[2] Baseball Magazine praised Bush for his range: "In the field Bush sometimes appears ragged, but this is not owing to lack of finish in handling stinging grounders. It is rather a direct result of his eagerness to spear everything within reach and just a little beyond. No chance is too hard for him to try, and more than most fielders can say he pulls down the drive and relays it to first."[30] In its annual selection of an All-America Baseball Team, Baseball Magazine named Bush as the second best shortstop in the American League, calling him "one of the cleverest fielders in the game" and citing "his unsurpassed ability to get on bases and his great speed and nice judgment in run-getting once he earns standing room on first."[31]

1914 season

editIn 1914, Bush led the American League with 721 plate appearances and 112 bases on balls while also scoring 97 runs and compiling 35 stolen bases and a .373 on-base percentage.[2] In the voting for the 1914 Chalmers Award (the predecessor of the American League Most Valuable Player award), Bush finished in a tie with Home Run Baker for third place, trailing only Eddie Collins and Sam Crawford, and ahead of Shoeless Joe Jackson, Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb.[2]

1915 season

editIn 1915, Bush, along with Detroit's all-star outfield of Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and Bobby Veach, helped lead the Tigers to a 100–54 record and a second-place finish in the American League.[32] Bush again led all American League players with 703 plate appearances and 504 assists and was again among the league leaders with 118 bases on balls (2nd), 99 runs (6th), 35 stolen bases (8th), 340 putouts at shortstop (2nd), 61 double plays turned at shortstop (2nd), 5.45 range factor at shortstop (2nd), and 57 errors (2nd).[2]

At the end of the 1915 season, J. C. Kofoed in Baseball Magazine rated Bush as the best shortstop in the American League. Kofoed wrote that Bush had only five fewer chances than Rabbit Maranville and seven fewer errors, noted that Bush made "spectacular plays" in the field "day after day".[20] Kofoed also dismissed those who relegated Bush to the "poor hitting class", noting that Bush got on base and scored more often than any of his Detroit teammates.[20] The Sporting Life that same year noted that Bush "is just about the most methodical and consistent person connected with our national game."[33]

In appreciation of Bush's efforts during the 1915 season, Detroit fans raised funds to allow Bush to purchase a new Paige automobile.[34] The Detroit Free Press wrote:

There never was a player who deserved a testimonial more than Donie deserves this one. The little infielder has been the mainstay of the Tigers' defense all season and has saved game after game by his sensational stunts. . . . Off the field he has never permitted his spirits to flag, declaring right up to the last minute that the Tigers were going to win the pennant. . . . Apart from baseball, Bush is a mighty fine fellow, good-natured, lively, generous, and the sort of man anyone would like to have for a friend.[35]

In January 1916, The Sporting Life reported that "Bush has been driving his new car most of the time since he left Detroit and is said to be only a few laps behind (Barney) Oldfleld as a speed merchant."[36]

1916 season

editIn 1916, Bush continued to rank among the American League leaders in multiple categories with 75 bases on balls (7th), 27 sacrifice hits (9th), 435 assists (5th among all players regardless of position), 278 putouts at shortstop (4th), and a .954 fielding percentage at shortstop (3rd).[2] Baseball Magazine, in choosing its All Star American League Team, chose Bush at the shortstop position. Writer F. C. Lane observed: "But the best performer, taking everything into consideration, was Donie Bush of Detroit. Bush is simply unsurpassable as a fielding shortstop and while a weak hitter according to the records he is nevertheless a dangerous man on the offensive through his well-known ability to secure free passage to first base and his amazing swiftness of foot once he reaches that initial station on the homeward journey."[37]

1917 season

editIn 1917, Bush led the American League with 112 runs scored, stole 34 bases, and compiled a career-high batting average of .281 with a .370 on-base percentage.[2] Bush also broke up a noteworthy no-hitter on July 11, 1917. With Boston Red Sox pitcher Babe Ruth having allowed no hits, Bush hit a scratch single in the eighth inning. After giving up the single to Bush, Ruth struck out the Tigers' Bobby Veach, Sam Crawford, and Ty Cobb in the ninth inning to secure a 1–0 complete game shutout. In a 1942 speech in Los Angeles‚ Ruth called this game his greatest thrill.[10] At the end of the 1917 season, Baseball Magazine rated Bush as the second best shortstop in the American League behind Ray Chapman. Writer F. C. Lane called him "one of the greatest ground coverers and all round fielders on any diamond."[38]

1918 season

editIn 1918, Bush's batting average dropped 47 points from the prior season to .234. Despite the drop in average, Bush continued to rank among the American League's leaders with 594 plate appearances (1st), 79 bases on balls (2nd), 280 putouts at shortstop (2nd), 74 runs scored (4th), and 48 errors (3rd).[2] Baseball Magazine that same year published a feature story on how a player's hands make him suitable for one position or another. The author wrote: "Donie Bush is a wonderful shortstop all will agree. Bush is a little man perhaps the shortest of stature in organized baseball. But his hand is very broad, thick and bony as well as freckled. It is a typical scoop hand."[39]

1919 season

editIn 1919, Bush continued to perform well defensively. His 290 assists at shortstop led the American League, and his .943 fielding percentage was third best among the league's shortstops. Offensively, he continued to rank among the league's leaders with 75 bases on balls (5th), 22 stolen bases (7th), and 82 runs scored (10th).[2] That same year, Bush authored an article in Baseball Magazine titled, "Inside Points on Playing Short."[40] Bush argued that shortstop was the toughest position on the infield:

You hear a lot of third baseman raving about the hard chances they get, but any time the shortstop is looking for a berth that is nice and quiet and restful in comparison to his own he casts longing glances at third. Look up the records and see what becomes of the shortstops who get too old to cover all the ground between second base and the foul line. A lot of them camp on third for a while. And why shouldn't they? A man can play third when he can't play short. That's a cinch.[40]

1920 season

editIn 1920, Bush led the American League with 48 sacrifice hits—the seventh highest total in Major League history.[12] Despite his advancing age, Bush retained considerable speed, stealing 15 bases and hitting 18 doubles and five triples.[2] Baseball Magazine in June 1920 noted: "Donie Bush is aging, yet gets around with tremendous agility."[41]

1921 season

editIn 1921, Ty Cobb took over from Hughie Jennings as manager of the Tigers. Bush became involved in repeated arguments with Cobb's "first lieutenant", Dan Howley. The Detroit Free Press wrote that Howley "never is quite so contented" as he is when arguing with Bush and added: "Bush would fight at the drop of a hat for Dan, yet the midget never gets nearly so mad at anyone as he does when Howley, with deliberate intent, corners Donie somewhere and starts a debate. . . . Often Donie becomes so enraged that he pulls his cap off his head and throwing it off the door of the hotel lobby or in the turf of the ball field, stamps on it in his hysteria."[42] For the first half of the season, Bush continued as the Tigers' starting shortstop. Halfway through the season, however, Cobb moved Bush from his regular shortstop position to second base.

In August 1921, Detroit owner Frank Navin placed Bush on waivers, ending his 13-year career with the Tigers.[43][44] The Sporting News reported on Bush's departure from Detroit as follows:

The passing of Bush removes one of the spectacular figures of Detroit baseball history. . . . Built low to the ground and extremely aggressive, Bush presented a spectacle that appealed to the heart of the gallery. He always did things in a sensational manner. His style made the hard ones look harder and the easy chances look hard. . . . Of Bush's fielding the outstanding feature always was his throwing. In that, more than in anything else, Bush stood apart. He had an uncanny ability to judge the speed of a runner on his way to first. He never seemed to hurry a throw, and he seemed never to throw with speed. Most of the time he apparently lobbed the ball but he always got his man, sometimes by a fraction of a step -- but he got him. This ability of Bush's was always a matter of amazement to spectators and they could never solve the riddle of it.[45]

Washington Senators

editIn late August 1921, Bush was selected off waivers by the Washington Senators and became the team's starting shortstop for the final 33 games of the 1921 season. In January 1922, the Senators acquired shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, relegating Bush to playing second and third base. Bush began the 1922 season on a hot streak at the plate. By mid-May, he was averaging a run every three at bats, a rate on par with Babe Ruth, leading The Sporting News to write that Bush was playing the best baseball of his life.[46] Bush appeared in 41 games for the 1922 Senators and finished the season with a .342 on-base percentage and 21 bases on balls in 158 plate appearances.[2]

Managerial career

editWashington Senators

editDespite having a line-up that included Baseball Hall of Famers Walter Johnson, Goose Goslin, Sam Rice, and Bucky Harris, the 1922 Senators finished the season with a 69–85 record and in sixth place in the American League.[47] In December 1922, Washington owner Clark Griffith hired Bush to replace Clyde Milan as player-manager for the 1923 season.[48][49] The Sporting News opined that Bush had the characteristics to make a solid manager: "The same traits that made our friend Donie a great little ball player have been recognized when Clark Griffith appoints him manager. Brains, a good pair of hands, and a bulldog disposition made him a playing success against the handicap of being undersized and rather weak of arm. . . . He ought to make quite a manager; ought to put something into that Washington team that it lacked."[50]

On August 2, 1923, Bush noticed early in a game that Hank Severeid and Wally Gerber of the St. Louis Browns had switched spots in the batting order and batted out of turn. In the second, fifth and seventh innings both players made outs, and Bush said nothing. In the ninth inning, Gerber hit a single with two out and a runner on first base. Bush appealed to the umpire that Gerber had batted out of order. Gerber was declared out to end the game.[51]

Bush led the 1923 Senators to a fourth-place finish and a 75–78 record, two positions higher in the standings and seven fewer losses than the 1922 team.[52] In October 1923, and despite the improved record, team owner Clark Griffith fired Bush as the team's manager. The shift drew criticism from the Washington press, and one newspaper even urged a boycott of the Senators over the firing of Bush. Griffith initially declined comment on his release of Bush, but as criticism intensified, Griffith said in a written statement that he found Bush "incompetent as a manager, failing to maintain discipline among the players, utter disregard of the development or use of young players, favoritism and indifference when the ball game was over as to ways or means of improving conditions."[53] The Senators went on to win the 1924 World Series under new manager Bucky Harris.[54]

Indianapolis Indians

editAfter being released by the Senators, Bush returned to his hometown where he was hired as the manager of the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association.[55][56] In July 1924, a "Bush Day" was held in Indianapolis with 10,000 fans showing up to honor Bush and present him with gifts.[57] In his first year as manager of the Indians, Bush led the Indians to a second-place finish in the American Association, narrowly losing the pennant to St. Paul in the final series of the 1924 season. His team again finished in second place in 1925, losing the pennant to Louisville.[58]

In 1926, Bush developed appendicitis during a road trip and returned to Indianapolis to undergo surgery.[59] After a period of convalescence, Bush returned to his role as manager and led the Indians to their third consecutive second-place finish.[60]

Pittsburgh Pirates

editIn October 1926, Bush was hired to replace Bill McKechnie as manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates.[60] The Pirates were loaded with talent but had finished in third place in 1926.[61] In Bush's first year in Pittsburgh, he led the 1927 Pirates to a National League pennant with a 94–60 record.[62] The Pirates were then swept by the soon-to-be famous New York Yankees in the World Series. During that season, Bush had a feud with Pirates star Kiki Cuyler. Cuyler was unhappy about being switched from third to second in the batting order, and he allegedly slackened his effort for a few games. Bush reacted by benching Cuyler in August and not playing him again for the rest of the season (using him sparingly for pinch hitting), even keeping him out of the World Series. Bush ignored chants from Pirate fans, "We want Cuyler! We want Cuyler", in the games at Pittsburgh. After the season, the Pirates traded the future hall of famer in Cuyler to the Cubs. Cuyler would make it to the World Series once more in his career while the Pirates would not contend again until 1960.[63][64]

Bush's Pirates finished in fourth place in 1928 and in second place in 1929. During the 1929 season, Bush complained to a Pittsburgh reporter about the new "lively ball", saying, "It's not a ball‚ it's a bullet. Somebody's going to get killed if they don't watch out. A pitcher who has to put the ball over hasn't a chance. All he can do is to pitch and duck."[10] (Bush's statement would prove incorrect, as no player has died on the field since Ray Chapman in 1920).

At the end of August 1929, Bush suddenly resigned as the Pirates' manager. At the time, The Sporting News noted that many of the Pittsburgh fans turned against Bush when he benched Cuyler in 1927 and that Bush had never been able to get the local fans behind him.[65]

Chicago White Sox

editOn September 30, 1929, Bush signed a two-year contract to serve as the manager of the Chicago White Sox starting with the 1930 season.[66] He took over a team that had finished in seventh place with a 59–93 record in 1929.[67] In 1930, the White Sox again finished in seventh place, improving only slightly to 64–90.[68]

By July 1931, a public debate was under way as to whether Bush or team owner Charles Comiskey was to blame for the White Sox' poor showing. Many in the press blamed Comiskey for the shortage of talent at Bush's command. During a July road trip to the East, the White Sox had only "five workable pitchers", a term The Sporting News defined as "those who could throw a ball."[69] Bush complained about the lack of "cooperation" from Comiskey in acquiring players as his 1931 team compiled both the lowest batting average (.260) and the highest earned run average (5.04) in the American League and dropped to eighth place with a 56–97 record.[70][71] Bush resigned at the end of the 1931 season.[72]

Minneapolis Millers

editIn 1932, Bush managed the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association to a 100–68 record and a first-place finish.[73]

Cincinnati Reds

editOn November 10, 1932, the Cincinnati Reds announced that they had two weeks earlier retained Bush as manager for the 1933 season.[74] Upon his hiring, one newspaper reporter predicted: "No bed of roses awaits the new manager here. . . . He falls heir to a run-down team, with little financial backing and a quick-to-criticize public."[75] The 1933 Reds finished in last place with a 58–94 record, compiled the lowest batting average (.246) in the National League, and lacked a pitcher who was able to muster more than 10 wins.[76]

Minneapolis Millers

editIn December 1933, Bush was hired as the manager of the Minneapolis Millers, the team he had coached in 1932.[77][78] He remained with the Millers from 1934 to 1938 and won pennants in 1934 and 1935.[73][79] Ted Williams played for the Millers in 1938, saw his batting average jump 75 points over the prior year, and later credited Bush with some of his success.[15] After learning that Bush had died, Williams said: "I've been in the game for 36 years and nobody has any closer affection to my heart than Ownie." He noted that Bush was as "fiery as a man could be...a man who tried to be tough but was as soft as a grape."[3]

Managerial Record

edit| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| WSH | 1923 | 153 | 75 | 78 | .490 | 4th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| WSH total | 153 | 75 | 78 | .490 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| PIT | 1927 | 154 | 94 | 60 | .610 | 1st in NL | 0 | 4 | .000 | Lost World Series (NYY) |

| PIT | 1928 | 152 | 85 | 67 | .559 | 4th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| PIT | 1929 | 118 | 67 | 51 | .568 | resigned | – | – | – | – |

| PIT total | 424 | 246 | 178 | .580 | 0 | 4 | .000 | |||

| CWS | 1930 | 154 | 62 | 92 | .403 | 7th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| CWS | 1931 | 153 | 56 | 97 | .366 | 8th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| CWS total | 307 | 118 | 189 | .384 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| CIN | 1933 | 152 | 58 | 94 | .382 | 8th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| CIN total | 152 | 58 | 94 | .382 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| Total | 1036 | 497 | 539 | .480 | 0 | 4 | .000 | |||

Team owner and executive

editLouisville Colonels

editIn September 1938, Bush announced that he was resigning his position as manager of the Minneapolis Millers to become a co-owner, general manager and field manager of the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. Bush and two partners, Indiana banker Frank E. McKinney and Tom Yawkey (owner of the Boston Red Sox), purchased the club reportedly for $175,000 -- $100,000 for the plant (including a 14,500-seat park built in 1923 for $400,000) and $75,000 for the franchise and players.[80][81]

After taking over the Colonels, Bush lauded the team's shortstop, Pee Wee Reese, as "the best-looking shortstop prospect he's seen in his 30-odd years in baseball."[82] In July 1939, Bush and McKinney recouped much of their investment by trading Reese to the Brooklyn Dodgers for $35,000 and three players. Co-owner Yawkey reportedly objected to the trade, but Bush and McKinney held a majority interest in the club.[10][82]

After the 1940 season, Bush and McKinney sold their two-thirds interest to Yawkey. Bush was in a St. Louis hospital at the time and stated that he was selling his interest in the team due to poor health.[83][84]

Indianapolis Indians

editBush remained a resident of Indianapolis throughout his life. He lived on the 200 block of North Walcott Street in east Indianapolis from at least 1910 through 1940.[5][6][7][16][85][86]

In December 1941, after Bush recuperated from a lengthy illness, Bush and McKinney bought the Indianapolis Indians from Norman Perry. Bush, who became the team's president as well as a co-owner, said at the time, "It always was my ambition, since I was a kid, to have a share in the ownership of the Indianapolis club."[87]

Bush and McKinney hired Gabby Hartnett as the team's field manager for 1942. In November 1942, Bush announced that he would take over as field manager in 1943 while continuing as the club's president as well.[79] Bush managed the team for the entire 1943 but was forced by ill health to give up his role as field manager in May 1944, hiring his long-time friend Mike Kelly to take over as the team's manager.[88]

On July 20, 1951, Bush and McKinney sold majority control of the Indianapolis baseball club to the Cleveland Indians.[89] On February 25, 1952, Bush was replaced as the club's president after holding the position for nearly 10 years. Bush continued to hold a minority interest in the club and remained with the club as an executive without title. The Sporting News noted that the reorganization marked the first time since Bush's playing days that he had been without an official title.[90] In November 1952, Bush and McKinney sold their remaining 25% interest in the Indianapolis club to the Cleveland Indians.[91]

For three years following his disassociation with the Indianapolis club, Bush worked as a scout for the Boston Red Sox.[92] In January 1956, Bush and McKinney led a successful effort to transform the Indianapolis club into a community-owned team through a public stock offering. On January 30, 1956, Bush was named president and general manager of the club.[93]

On February 1, 1969, Bush announced that he was resigning as the club's president after holding the position continuously since 1956. Bush, who was 81 years old, stated that he was quitting as the result of "a front-office squabble" with the club's chairman, Louis Hensley, and general manager, Max Schumacher.[92]

Later years and honors

editBush remained affiliated with professional baseball for 65 years. He was given the title "King of Baseball" during Major League Baseball's 1963 winter meetings.[22] In 1967, the stadium in which the Indianapolis Indians played was renamed from Victory Field to Bush Stadium in his honor.[14][22]

In 1972, at age 84, Bush was working as a scout for the Chicago White Sox. He fell ill during spring training in Florida and died three weeks later after returning home to Indianapolis.[14][15] Bush was posthumously elected to the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979 and was known as "Mr. Baseball" in Indianapolis.[22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Sources differ as to Bush's date of birth. Sources listing the date as October 8, 1887, include (i) baseball-reference.com, and (ii) findagrave.com. Sources listing the date as October 3, 1887, include (i) United States Social Security Death Index for Owen Bush of Indianapolis (SSN 317-05-4538). Sources listing the date as October 8, 1888, include (i) a World War I Draft Registration Card (showing 10/8/88 date of birth and Indianapolis place of birth) completed by Owen J. Bush, residing at 207 Alcott in Indianapolis, height "short", working as a ball player in Detroit, and (ii) a World War II Draft Registration Card (showing 10/8/88 date of birth and Indianapolis place of birth) completed by Owen Joseph Bush of Indianapolis.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Donie Bush". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Jim Moyes (2006). "Donie Bush". SABR.

- ^ 1900 Census entry for Ellen Bush (born September 1858 in Kentucky, the daughter of Irish immigrants) and family. Daughter Lizzie born Jan. 1882 (father born in Ireland). Son Michael born Nov. 1886 (father born in Ireland). Son Owen born Oct. 1888 in Indiana (father born in Ireland). Source Citation: Year: 1900; Census Place: Center, Marion, Indiana; Roll: 389; Page: 8B; Enumeration District: 0114; FHL microfilm: 1240389. Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ a b 1910 Census entry for Ellen Bush (age 52, born in Kentucky of Irish immigrants) and family residing at 206 Walcott in Indianapolis. Daughter Elizabeth age 26. Son Michael age 23. Son Owen age 21 born in Indiana employed as a "Ball Player" with the "Detroit Team". Source Citation: Year: 1910; Census Place: Indianapolis Ward 9, Marion, Indiana; Roll: T624_368; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 0161; FHL microfilm: 1374381. Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ a b 1920 Census entry for Ellen Bush (age 62, born in Kentucky) and family residing at 207 N. Walcott in Indianapolis. Son Michael (age 34). Son Owen (age 32) born in Indiana employed as a "ball player". Source Citation: Year: 1920; Census Place: Indianapolis Ward 9, Marion, Indiana; Roll: T625_454; Page: 5B; Enumeration District: 167; Image: 233. Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ a b 1930 Census entry for Owen Bush (age 40, born in Indiana, employed as a baseball manager) and his mother Elizabeth (age 68), both residing at 207 N. Walcott in Indianapolis. Source Citation: Year: 1930; Census Place: Indianapolis, Marion, Indiana; Roll: 612; Page: 18B; Enumeration District: 0128; Image: 445.0; FHL microfilm: 2340347. Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Putouts as SS". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ "Chance Records for Shortstops". Baseball-Almanac.com. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Donie Bush". baseballlibary.com.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Bases on Balls". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Sacrifice Hits". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ J. C. Kofoed (1920). "Ten Leading Stars in Recent Baseball Records" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ a b c d "Donie Bush Dies; Led Ball Teams; Shortstop in Cobb's Time Later Managed 4 Clubs". The New York Times. March 29, 1972. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Obituaries: Owen J. (Donie) Bush". The Sporting News. April 15, 1972. p. 30. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Donie Bush Minor League Statistics". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ "The Central League" (PDF). The Sporting Life. August 11, 1906. p. 12.

- ^ "The Central League" (PDF). The Sporting Life. December 15, 1906. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d "Who's Who In Baseball" (PDF). Baseball Magazine. 1908. p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e J. C. Kofoed (1915). "The Greatest Shortstop in the American League: Owen Bush and His Great Record with Detroit -- What He Has Done for the Tigers" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ "The American Association" (PDF). The Sporting Life. December 12, 1908. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d "Inductee — Owen Joseph Bush". The Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Paul Bruske (September 26, 1908). "Detroit's Dole" (PDF). The Sporting Life. p. 8.

- ^ "American Association News" (PDF). The Sporting Life. August 22, 1908. p. 14.

- ^ "Bush Is Added To Men Signed: Speedy Little Infielder Turns in Contract, and Says He Is Satisfied". Detroit Free Press. January 20, 1909. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Bush Calls But Does Not Sign: Comes to Town With Bowlers and Makes Side Trip to Ball Club Office". Detroit Free Press. March 6, 1910. p. 17. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Owen Bush Is Tiger for 1910: Little Shortstop Signs His Gontract but Misses Train for Southland". Detroit Free Press. March 13, 1910. p. 17.

- ^ "Baseball Awards Voting for 1911". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ "Donie Bush's Distinction" (PDF). The Sporting Life. December 14, 1912. p. 8.

- ^ F. C. Lane (1913). "The Greatest of All Shortstops" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ F. C. Lane (1913). "The All America Baseball Club" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ "1915 Detroit Tigers". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Chandler Richter (January 9, 1915). "Side-Lights on Baseball" (PDF). The Sporting Life. p. 10.

- ^ "Donie Bush Now Is Auto Owner: Tigers' Shortstop Buys Paige Detroit Car With Money Donated by Fans Who Admire Him". Detroit Free Press. October 16, 1915. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Donie Bush Testimonial Lists Close Saturday: Fans Who Wish to Be in on Presentation to Tigers' Great Shortstop Will Have to Step Lively". Detroit Free Press. October 2, 1915. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Doings At Detroit" (PDF). The Sporting Life. January 15, 1916. p. 6.

- ^ F. C. Lane (1916). "The All-America Baseball Club" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ F. C. Lane (1917). "The All-America Baseball Team" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ F. C. Lane (1918). "Inside Dope From A Ball Player's Hands" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ a b Donie Bush (1919). "Inside Points on Playing Short" (PDF). Baseball Magazine.

- ^ "Striking Incidents of the Season's Opening" (PDF). Baseball Magazine. June 1920. p. 332.

- ^ "Howley and Donie Renew Fight: "Friendly Enemies" Are Never Happy Unless They Are Battling Each Other". Detroit Free Press. March 13, 1921. p. 23. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Bullion, Harry (August 18, 1921). "Donie Bush Will Leave Tigers By Waiver Route: Service of Thirteen Years in Tiger Spangles is at End; Midget Might Land With Some Other Club in American League; Donie's Friends Certain to Express Regrets at His Departure". Detroit Free Press. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Tigers Have Decided to Release Shortstop Star of Former Years". Detroit Free Press. August 18, 1921. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Release of Bush First Step In Cobb's Plans For Rebuilding". The Sporting News. August 25, 1921. p. 1.

- ^ "Comeback of Bush Is One Bright Spot: Donie Playing Best Ball of His Career for Griffs". The Sporting News. May 11, 1922. p. 3.

- ^ "1922 Washington Senators". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "Bush to Pilot Senators". Detroit Free Press. December 14, 1922. p. 20. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Donie Bush Sort of Fighter Who Ought To Be Successful Leader: Former Tiger Flash Has One of the Rare Assets of Major League Managers--Different From His Predecessors". Detroit Free Press. December 23, 1922. p. 16. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Here's Hoping, Donie". The Sporting News. December 21, 1922. p. 4.

- ^ "Out of Turn". retrosheet.org.

- ^ "1923 Washington Senators". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ "Carrying It Pretty Far In Washington: One Paper Would Boycott Club For Releasing Bush; Time Will Show That Griffith Is Not Taking Action Tending To Destroy His Own Investment". The Sporting News. November 1, 1923. p. 3.

- ^ "1924 Washington Senators". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "His Old Hometown Goes Wild Over Him: Manager Donie Bush". The Sporting News. May 1, 1924. p. 4.

- ^ J.F. McCann (May 1, 1924). "Donie Bush Bringing Baseball Back To Life In Indianapolis: Former Major League Shortstop Star, Who First Broke Into Prominence In Hoosier Capital, Now Heads Old Team Towards Flag". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ J.F. McCann (July 17, 1924). "Donie Bush Loses Services of a Pair". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ J.F. McCann (October 22, 1925). "Owen Bush Re-Engaged As Indianapolis Manager: Announcement Comes As Good News To Followers Of Hoosiers Who Feared Little Pilot Would Carry Out Threat To Quit Home Town". The Sporting News. p. 6.

- ^ J.F. McCann (July 1, 1926). "Ed Sicking Pinch Hits For Boss and Delivers: Indianapolis Team Makes Advance in Flag Race on Long Road Trip With Bush Laid Up by Operation". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Donie Bush Named To Pacify Pirates: M'Kechnie's Successor Has Fine Record In Indianapolis; New Manager, For Many Years a Shortstop With Detroit, Handled Washington Team Successfully in 1923". The Sporting News. October 28, 1926. p. 1.

- ^ "1926 Pittsburgh Pirates". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "1927 Pittsburgh Pirates". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Ronald T. Waldo (2012). Hazen "Kiki" Cuyler: A Baseball Biography. McFarland. pp. 95–100. ISBN 978-0786468850.

- ^ David Finoli, Bill Ranier (2003). The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 444. ISBN 1582614164.

- ^ Ralph S. Davis (September 5, 1929). "Bush Can Charge Much To Bad Luck: Fans Never Gave Donie a Break After His Benching of Cuyler". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ "Bush Has Two-Year Contract with White Sox: Former Pirate Leader Succeeds Blackbourne as Chief; Little Fellow One of Great Shortstops of A.L. In His Heyday". The Sporting News. October 3, 1929. p. 1.

- ^ "1929 Chicago White Sox". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "1930 Chicago White Sox". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ Vaughan, Irving (August 6, 1931). "Bush's Flare-Up Indicates New Pilot For White Sox Next Year: Comiskey Refuses to Accept Blame for Failure of Team". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ "1931 Chicago White Sox". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "1931 American League". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ "Fonseca Acclaimed As Moses For Sox: Donie Bush Quits, Following City Series". The Sporting News. October 15, 1931. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Millers Year by Year". Stew Thornley. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ "Signing of Bush as Reds' Pilot Discloses M'Graw Rejected Job: Contract for One Year; Pay Not Revealed". The Sporting News. November 17, 1932. p. 1.

- ^ Tom Dacey (November 18, 1933). "Donie Bush Shows Gameness: His Signature On Reds' Contract Means Hard Labor". The Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 15.

- ^ "1933 Cincinnati Reds". baseball-reference.

- ^ "Donie Works Without Contract". The Sporting News. December 21, 1933. p. 6.

- ^ Halsey Hall (December 28, 1933). "Kelley and Bush Begin Rebuilding Millers; Fans Happy Over Donie's Return". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ a b W. Blaine Patton (November 12, 1942). "Bush Back in Harness as Indianapolis Pilot: Takes Over Reins From Gabby Hartnett and Will Double as Club President". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ Bruce Dudley (September 15, 1938). "Louisville Hails Bush-Red Sox Purchase; Price Under $200,000". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ Halsey Hall (September 15, 1938). "Bush Aided in Deal by Indianapolis Banker". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ a b Tommy Fitzgerald (February 1, 1940). "Nimble Hands and Feet Led Brooklyn To Nab Reese, Who Hopes To Run Durocher Off Shortstop Job". The Sporting News. p. 3.

- ^ "Colonels Acclaim Burwell As Pilot". The Sporting News. October 17, 1940. p. 7.

- ^ "Bosox May Expand in Farm Ownership: Full Title Acquired at Louisville, Marking Change in Policy". The Sporting News. October 24, 1940. p. 3.

- ^ 1940 Census entry for Owen J. Bush (age 52, employed as the owner of a baseball club) residing at 207 N. Walcott in Indianapolis. Also living at the house was Bush's sister Elizabeth, her husband Robert V. Fessler (a wood carpenter for the post office), and sister Mary Bush (age 65). Source Citation: Year: 1940; Census Place: Indianapolis, Marion, Indiana; Roll: T627_1126; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 96-170. Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census [database on-line].

- ^ The World War II Draft Registration Card completed by Owen Joseph Bush (available on-line at ancestry.com) lists his address as 207 N. Walcott, Indianapolis, his date of birth as October 8, 1888, his place of birth as Indianapolis, and his principal contact person as Paul Sullivan.

- ^ W. Blaine Patton (December 11, 1941). "Hartnett Shuffled Into Indianapolis' New Deal: Popular National League Catcher Named Manager After McKinney and Bush Assume Control of Team". The Sporting News. p. 1.

- ^ "Pointer From New Boss". The Sporting News. May 18, 1944. p. 44.

- ^ Hal Lebovitz (August 1, 1951). "Indianapolis Club Bought By Tribe To Build Up Farms". The Sporting News. p. 14.

- ^ "Indianapolis Club Reorganizes". The Sporting News. March 5, 1952. p. 34.

- ^ "Indians Take Over Complete Ownership of Indianapolis". The Sporting News. November 5, 1952. p. 18.

- ^ a b "Donie Bush Retiring -- In Baseball Since '03". The Sporting News. February 15, 1969. p. 45.

- ^ Les Koelling (February 8, 1956). "Bush to Operate Fan-Owned Club at Indianapolis: Named Prexy of Indians; McKinney to Head Board". The Sporting News. p. 31.

External links

edit- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Retrosheet

- Donie Bush managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Donie Bush at the SABR Baseball Biography Project