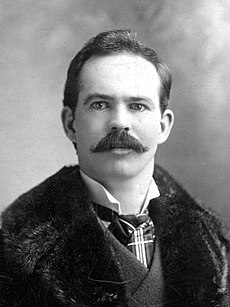

Donald Henderson Bain (February 14, 1874 – August 15, 1962) was a Canadian amateur athlete and merchant. Though he competed and excelled in numerous sports, Bain is most notable for his ice hockey career. While a member of the Winnipeg Victorias hockey team from 1894 until 1902, Bain helped the team win the Stanley Cup as champions of Canada three times. A skilled athlete, he won championships and medals in several other sports and was the Canadian trapshooting champion in 1903. In recognition of his play, Bain was inducted into a number of halls of fame, including the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1949. He was also voted Canada's top athlete of the last half of the 19th century.

| Dan Bain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hockey Hall of Fame, 1949 | |||

| |||

| Born |

February 14, 1874 Belleville, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Died |

August 15, 1962 (aged 88) Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada | ||

| Height | 6 ft 0 in (183 cm) | ||

| Weight | 185 lb (84 kg; 13 st 3 lb) | ||

| Position | Centre | ||

| Shot | Right | ||

| Played for | Winnipeg Victorias | ||

| Playing career | 1894–1902 | ||

In his professional life Bain was a prominent Winnipeg businessman and community leader. He became wealthy as a result of operating Donald H. Bain Limited, a grocery brokerage firm. Bain was an active member of numerous community associations, the president of the Winnipeg Winter Club and an avid outdoorsman. The Mallard Lodge, a building on the shores of Lake Manitoba built by Bain as a personal retreat, today serves as a research facility for the University of Manitoba.

Early life

editThe son of Scottish immigrants, Bain was born in Belleville, Ontario, and as a young child moved with his family to Winnipeg, Manitoba.[1] His father, James Henderson Bain, was a horse buyer for the British government and upon his arrival in Canada lived in Montreal before moving west. His mother, Helen Miller, was a seamstress. Bain was the sixth of seven children, having four sisters and two brothers.[2] Bain attended school in Winnipeg and earned a bachelor's degree from Manitoba College.[1] He began working in 1888, aged 14, serving as a bookkeeper's apprentice for a grocery broker.[3]

Sporting career

editBain's first championship came in 1887 when he captured the Manitoba roller skating title at the age of 13 by winning a three-mile race.[4] At the age of 17, he won the Manitoba provincial gymnastics competition, and at 20 won the first of three consecutive Manitoba cycling championships. Bain was also a top lacrosse player in his home province.[5]

In 1895 Bain first played competitive ice hockey when he answered a classified ad placed in a newspaper by the Winnipeg Victorias, who were looking for new players. Though he played with a broken stick held together by wire, Bain made the team only five minutes into the tryout.[4] He quickly became a star centre and leader of the Victorias. This was proven during a February 14, 1896, game against the Montreal Victorias for the Stanley Cup, the trophy for the national hockey championship in Canada. Bain scored a goal in a 2–0 win for Winnipeg that gave them the Cup.[6] This victory marked the first time a team outside of Quebec had won the Stanley Cup.[7] A huge crowd greeted the team at the Canadian Pacific Railway station when their train, decorated with hockey sticks and the Union Jack, returned to Winnipeg. They were led in a parade of open sleighs to a feast in their honour, where fans gathered to celebrate the championship.[4]

The Montreal Victorias played Winnipeg in a challenge to reclaim the Cup in December 1896, a game described by the local press as "the greatest sporting event in the history of Winnipeg".[8] Though Bain scored two goals in the game, Montreal recaptured the Cup with a 6–5 victory.[9] Winnipeg was involved in many other Stanley Cup challenges with Bain serving as the team's captain and manager. They lost again to their Montreal counterparts in 1898 before a record crowd of over 7,000 fans.[10]

During a 1900 challenge series against the Montreal Shamrocks, Bain scored four goals in three games, but Winnipeg again lost the title.[11] The Victorias next challenged the Shamrocks in 1901 in a best-of-three series. Winnipeg won the series in two games after Bain scored the clinching goal in overtime.[12] It was the first time in Stanley Cup history that the winning goal was scored in extra time.[9] Bain did so while playing with a broken nose that required him to wear a wooden face mask, earning him the nickname "the masked man" as a result.[9] When the Victorias defended their title in a series against the Toronto Wellingtons in January 1902, Bain did not play in the series.[13] The team lost their next challenge against the Montreal Hockey Club, in March of that year, which marked the end of Bain's hockey playing career.[14] In 1911 and 1912 the Victorias, with Bain as honorary president, won the Allan Cup, which replaced the Stanley Cup as the top amateur hockey trophy in Canada in 1909. They were the first team from Western Canada to win the trophy.[15]

Throughout his sporting career, Bain also earned medals in lacrosse and snowshoeing. He was the Canadian trapshooting champion in 1903.[4] An avid figure skater throughout much of his life, Bain won over a dozen titles, the last of which came at the age of 56. He continued to skate until the age of 70,[16] and he remained a competitive athlete until 1930.[5] On his skill in a variety of sports, Bain once said, "I couldn't see any sense in participating in a game unless I was good. I kept at a sport just long enough to nab a championship, then I'd try something else."[4]

In recognition of his sporting skill, Bain was inducted into several halls of fame. In 1945 when the Hockey Hall of Fame was founded, he was one of the initial 12 players selected.[17] In 1949 he was elected a member of the International Hockey Hall of Fame.[18][19] This was followed in 1971 by his induction into Canada's Sports Hall of Fame, the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame and Museum in 1981 (as an individual; he would be inducted again in 2004 along with the 1911 and 1912 Winnipeg Victorias teams), and the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame.[5][16][15][20] Bain was also voted Canada's top sportsman of the last half of the 19th century.[9][21]

Personal life

editApart from sports, Bain was a well-known Winnipeg businessman. From his first job as a bookkeeper's apprentice at a grocery broker, he moved up to junior partner when the business was sold to one of his neighbours. By 1905 his name was added to the company's, creating Nicholson and Bain; the firm prospered, with offices across Western Canada.[3] This partnership ended in 1917 due to differences in lifestyle between the two men. Bain renamed the firm after himself, Donald H. Bain Limited, and served as president.[22][23] It was through his firm that he amassed a large fortune, and purchased several properties in and around Winnipeg.[24][22] Though reserved in his personal life, Bain was known as a community leader. He helped found the Winnipeg Winter Club on land that is now the home of the HMCS Chippawa naval reserve division. After the Second World War, he organized the current Winter Club.[5] Bain also belonged to many community groups, including the Freemasons, and was the life governor of the Winnipeg General Hospital.[22] He was also one of Western Canada's first automobile enthusiasts and owned many British vehicles. He served for a time as president of the Winnipeg Automobile Club.[5][22]

As a trap-shooter, Bain developed an appreciation for nature. He bought an ownership share in the Portage Country Club, on the Delta Marsh near the south shore of Lake Manitoba, and later donated the land to Ducks Unlimited.[23][5][24] Bain built the Mallard Lodge as a personal retreat on land adjacent to the club. He strictly enforced his privacy, even building a road to his lodge that he allowed no one else to use; members of the Portage Country Club were required to take a different route.[24] Bain intended to donate his lodge to the government of Manitoba for preservation, though he died before he could do so. The lodge passed into the control of the government regardless, and in 1966 was donated to the University of Manitoba as a research facility that remains active today.[24] Bain was also a member of the Manitoba Game and Fish Association and the Winnipeg Humane Society.[23]

Bain never married and had no children.[24] A quiet and reserved individual after his playing career, Bain earned a reputation as a workaholic, and was described by a friend as "salty in speech and strongly opinionated."[25] Bain upheld a strong moral code, including abstaining from alcohol, and led a frugal lifestyle.[25] He was fond of his pets, in particular his Curly Coated Retriever dogs that he was said to value above human company.[24] On August 15, 1962, Bain died in Winnipeg, aged 88. He left an estate in excess of C$1 million, ($9.88 million in 2023 dollars),[26] the majority of which he donated to charity and former employees.[23] He was buried in the cemetery of St. John's Cathedral in Winnipeg.[27]

Career statistics

editRegular season and playoffs

edit| Regular season | Playoffs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Team | League | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | ||

| 1894–95 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 3 | 10 | 0 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1895–96 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 5 | 10 | 3 | 13 | — | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | — | ||

| 1896–97 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 5 | 7 | 1 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1897–98 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 5 | 13 | 1 | 14 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1898–99 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 3 | 11 | 1 | 12 | — | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1899–1900 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 2 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | — | ||

| 1900–01 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | — | ||

| 1901–02 | Winnipeg Victorias | MHL | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Totals | 27 | 66 | 7 | 73 | — | 11 | 10 | 0 | 10 | — | ||||

Notes

edit- ^ a b Goldsborough 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Goldsborough, Gordon (1996). "History of the University Field Station (Delta Marsh): Donald H. Bain (1874–1962)" (PDF). University of Manitoba. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ a b Goldsborough 2016, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e McKinley 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c d e f Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame. "Honoured Members – Dan Bain". SportManitoba.ca. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Coleman 1966, pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Winnipeg Victorias 1895–96Feb". Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ McKinley 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Hockey Hall of Fame. "The Legends – Dan Bain". LegendsofHockey.net. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Montreal Victorias 1897–98". Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Coleman 1966, pp. 57–58.

- ^ "Winnipeg Victorias 1901". Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Coleman 1966, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Coleman 1966, pp. 72–74.

- ^ a b Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame. "1911 & 1912 Winnipeg Victorias". SportManitoba.ca. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Honoured Members – Donald "Dan" Bain". Canada's Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Dan Bain Biography". Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Ross One of Two New Men Elected to Hall of Fame". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. Canadian Press. 22 October 1949. p. 18. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Two Members Added to Hall of Fame". Ottawa Citizen. Canadian Press. 21 October 1949. p. 30. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Honoured players – Dan Bain". Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ McKinley 2006, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Goldsborough 2016, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Goldsborough, Gordon (31 March 2017). "Donald Henderson "Dan" Bain (1874–1962)". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldsborough, Gordon (2007). "Mallard Lodge: Home of a marsh monarch" (PDF). Ducks Unlimited Canada Conservator. pp. 17–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ a b Goldsborough 2016, p. 29.

- ^ 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 17 April 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Goldsborough 2016, p. 32.

References

edit- Coleman, Charles L. (1966). The Trail of the Stanley Cup. Vol. 1: 1893–1926. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0-8403-2941-5.

- Goldsborough, Gordon (Spring 2016). "Dan Bain: The Squire of Delta Marsh". Manitoba History (80).

- McKinley, Michael (2006). Hockey: A People's History. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-5769-5.

External links

edit- Biographical information and career statistics from Eliteprospects.com, or Hockey-Reference.com, or Legends of Hockey