The Crown Colony of Labuan was a Crown colony off the northwestern shore of the island of Borneo established in 1848 after the acquisition of the island of Labuan from the Sultanate of Brunei in 1846. Apart from the main island, Labuan consists of six smaller islands; Burung, Daat, Kuraman, Papan, Rusukan Kecil, and Rusukan Besar.

Crown Colony of Labuan Pulau Labuan | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1848–1946 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: God Save the Queen (1848–1901) God Save the King (1901–1946) | |||||||||||||||||||

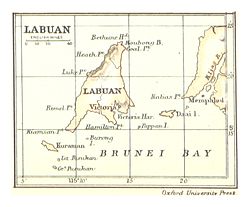

Map of Labuan, 1888 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Malay and Chinese etc. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1848–1876 | Queen Victoria (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1936–1946 | George VI (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1848–1852 | James Brooke (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1946 | Shenton Thomas (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | British Empire | ||||||||||||||||||

• Establishment of the crown colony | 1848 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Transferred to North Borneo | 1890 | ||||||||||||||||||

• British government rule | 1904 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Incorporated into Straits Settlements | 1 January 1907 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 January 1942 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10 June 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Labuan to North Borneo Crown | 15 July 1946 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1864[1] | 2,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1890[2] | 5,853 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1911[3] | 6,545 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1941[4] | 8,963 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | North Borneo dollar (1890–1907) Straits dollar (1907–1939) Malayan dollar (1939–1946) | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Malaysia ∟ Labuan | ||||||||||||||||||

Labuan was expected by the British to be a second Singapore, but it did not fulfill its promise especially after the failure of its coal production that did not become fruitful, causing investors to withdraw their money, leaving all machinery equipment and Chinese workers that had entered the colony previously. The Chinese workers then began involving themselves in other businesses with many becoming chief traders of the island's produce of edible bird's nest, pearl, sago and camphor, with the main successful production later being the coconut, rubber and sago.

World War II brought the invasion of Japanese forces which abruptly ended British administration. Subsequently, Labuan became the place where the Japanese commander in Borneo surrendered to the Allied forces, with the territory placed under a military administration before merging into the Crown Colony of North Borneo.

History

editFoundation and establishment

editSince 1841, when James Brooke had successfully established a solid presence in northwestern Borneo with the establishment of the Raj of Sarawak and began to assist in the suppression of piracy along the island coast, he had persistently promoted the island of Labuan to the British government.[5] Brooke urged the British to establish a naval station, colony or protectorate along the northern coast to prevent other European powers from doing so which being responded by the Admiralty with the arrival of Admiral Drinkwater Bethune to look for a site for a naval station and specifically to investigate Labuan in November 1844,[6] along with Admiral Edward Belcher with his HMS Samarang (1822) to survey the island.[7][8]

The British Foreign Office then appointed Brooke as a diplomat to Brunei in 1845 and asked him to co-operate with Bethune. At the same time, Lord Aberdeen who was the British Foreign Minister at the time sent a letter to the Sultan of Brunei requesting the Sultan to not enter any treaties with other foreign powers while the island was under consideration as a British base.[6] On 24 February 1845, Admiral Bethune with his HMS Driver and several other political commissions left Hong Kong to survey the island more. The crews found that it was the most suitable for inhabitants than any other island in the coast of Borneo especially with its coal deposits.[9] The British also saw the potential the island could be the next Singapore.[10] Brooke acquired the island for Britain through the Treaty of Labuan with the Sultan of Brunei, Omar Ali Saifuddin II on 18 December 1846.[11]

Captain Rodney Mundy visited Brunei with his ship HMS Iris (1840) to keep the Sultan in line until the British government made a final decision to take the island and he took Pengiran Mumin to witness the island's accession to the British Crown on 24 December 1846.[12][13] Brooke supervised the transferring process and by 1848, the island was made a crown colony and free port with him appointed as the first Governor.[14][15][16] From 1890, Labuan came to be administered by the North Borneo Chartered Company before been reverted to British government rule in 1904.[17][18] By 30 October 1906, the British government proposed to extend the boundaries of the Straits Settlements to include Labuan. The proposal took effect from 1 January 1907, with the administration area being taken directly from Singapore, the capital of the Straits Settlements.[3][19]

World War II and decline

editAs part of the World War II, the Japanese navy anchored at Labuan on 3 January 1942 without being met by any strong resistance.[20] Most treasury notes on the island had been burned and destroyed by the British to prevent them from falling into Japanese hands.[21] The remaining Japanese forces then proceeded to Mempakul in the western coast of neighbouring North Borneo to strengthen their main forces there.[22] Following the complete takeover of the rest of Borneo island, Labuan was ruled as part of the Empire of Japan and garrisoned by units of the Japanese 37th Army, which controlled northern Borneo. The island was renamed Maeda Island (前田島, Maeda-shima) after Marquis Toshinari Maeda, the first commander of Japanese forces in northern Borneo.[23][24] The Japanese planned to construct two airfields on the island with eleven others to be located in different parts of Borneo.[25][26][27] To achieve this, the Japanese brought approximately one hundred thousand Javanese forced labourers from Java to work for them.[26][28]

The liberation of the whole of Borneo began on 10 June 1945 when the Allied forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur and Lieutenant-General Leslie Morshead landed at Labuan with a convoy of 100 ships.[29] The 9th Australian Division launched an attack, with its 24th Brigade landing two battalions at the island southeast protrudance and the north side of Victoria Harbour on Brown Beach while being supported by massive air and sea bombardments.[30][31] The landings were witnessed by MacArthur on board the USS Boise (CL-47) when he decided to proceed further south from the southern Philippines to Labuan.[32] Following the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945, Lieutenant General Masao Baba who was the last commander of the Japanese army in northern Borneo surrendered at the island's Layang-layang beach on 9 September 1945. He was then brought to the 9th Division headquarters on the island to sign the surrender document in front of the commander of the 9th Division, Major General George Wootten.[33] The official surrender ceremony was held on the next day on 10 September at Surrender Point.[34] The town of Victoria had been damaged by Allied bombings but was rebuilt after the war. The island assumed its former name and was under British Military Administration (BMA) along with the rest of the British territories in Borneo before joining the Crown Colony of North Borneo on 15 July 1946.[17][4]

Governor

editFollowing the acquisition of Labuan, it was made a crown colony and governed by a Governor. Governor John Fitzpatrick imported a group of Dublin policemen to clean up the island and enforce health regulations during his term.[35] From the 1880s, there had been a wide disenchantment over the position of Labuan as a crown colony among British administrators after the failure of coal production,[36] causing the administration to be passed twice to North Borneo and the Straits Settlements.[37] From the last years of British rule, the authorities encouraged the involvement of indigenous natives in the island to participate in politics although it was still controlled based on the interests of the British government.[38]

Economy

editSince its discovery by the British, coal has been found on the main island.[7] Other economic resources include edible bird's nest, pearl, sago, and camphor.[1] The British hoped that the island's capital would grow into a city to rival Singapore and Hong Kong, but the dream was never realised. In particular the decline of coal production caused most investors to withdraw their investment.[36][39][40] As a replacement, coconut, rubber, and sago production became the main resources of the Labuan economy.[17] Under the administration of North Borneo, its revenue was $20,000 in 1889, increasing to $56,000 in 1902. Imports in 1902 were $1,948,742, while exports reached $1,198,945.[2]

Society

editDemography

editThe island had a population of about 2,000 in 1864,[1] 5,853 in 1890,[2] 6,545 in 1911,[3] and 8,963 in 1941.[4] The population is mainly Malays (mostly Bruneian and Kedayan) and Chinese, with a remainder of European and Eurasian. The Europeans were mainly government officials and staff of companies, the Chinese were the chief traders with most of the industries in the island in their hands, while the Malays were mostly fishermen.[39][2]

Public service infrastructure

editA telegraph line was established from Labuan to Sandakan on neighbouring North Borneo in 1894.[41] Postal services were also available throughout the administration, with a post office operating on the island by 1864 and used a circular date stamp as a postmark. The postage stamps of India and Hong Kong were used on some mail, but they were probably carried there by individuals rather than being on sale in Labuan. Mail was routed through Singapore. From 1867, Labuan officially used the postage stamps of the Straits Settlements but began issuing its own in May 1879.[42][43]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b c Geography of British Colonies 1864, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Hong Kong Daily Press Office 1904, p. 792.

- ^ a b c Hong Kong Daily Press Office 1912, p. 1510.

- ^ a b c Steinberg 2016, p. 225.

- ^ Saunders 2013, p. 75.

- ^ a b Wright 1988, p. 12.

- ^ a b Wise 1846, p. 70.

- ^ anon 1846, p. 365.

- ^ Stephens 1845, p. 4.

- ^ Evening Mail 1848, p. 3.

- ^ Yunos 2008.

- ^ anon 1847, pp. 1.

- ^ Saunders 2013, p. 78.

- ^ anon 1848, p. 4.

- ^ Wright 1988, p. 13.

- ^ Abbottd 2016, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Olson & Shadle 1996, p. 645.

- ^ Welman 2017, p. 162.

- ^ Keltie 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Rottman 2002, p. 206.

- ^ Hall 1958, p. 255.

- ^ Grehan & Mace 2015, p. 227.

- ^ Evans 1990, p. 30.

- ^ Tarling 2001, p. 193.

- ^ FitzGerald 1980, p. 88.

- ^ a b Kratoska 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Chandran 2017.

- ^ Ooi 2013, p. 1867.

- ^ Pfennigwerth 2009, p. 146.

- ^ Rottman 2002, p. 262.

- ^ Horner 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Gailey 2011, p. 343.

- ^ Labuan Corporation (1) 2017.

- ^ Labuan Corporation (2) 2017.

- ^ Lack 1965, p. 470.

- ^ a b Wright 1988, p. 91.

- ^ Wright 1988, p. 100.

- ^ Anak Robin & Puyok 2015, p. 16.

- ^ a b Clark 1924, p. 194.

- ^ London and China Telegraph 1868, p. 557.

- ^ Baker 1962, p. 134.

- ^ Armstrong 1920, pp. 35.

- ^ Hall 1958, p. 68.

References

edit- Stephens, John (1845). "Borneo". South Australian Register. Trove.

- anon (1846). The New monthly magazine and universal register. [Continued as] The New monthly magazine and literary journal (and humorist) [afterw.] The New monthly (magazine). Vol. 76. Publisher not identified.

- Wise, Henry (1846). A Selection from Papers Relating to Borneo and the Proceedings at Sarāwak of James Brooke ... Publisher not identified.

- anon (1847). "The island of Labuan". Geelong Advertiser and Squatters' Advocate. Trove.

- anon (1848). "Opening of the New Colony of Labuan". The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser. Trove.

- Evening Mail (1848). "Labuan". The Straits Times. National Library Board.

- Geography of British Colonies (1864). Geography of the British colonies and dependencies. Publisher not identified.

- London and China Telegraph (1868). The London and China Telegraph: 1868. Publisher not identified.

- Hong Kong Daily Press Office (1904). The Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Malay States, Sian, Netherlands India, Borneo, the Philippines, &c: With which are Incorporated "The China Directory" and "The Hong Kong List for the Far East" ... Hong Kong Daily Press Office.

- Hong Kong Daily Press Office (1912). The Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Malay States, Sian, Netherlands India, Borneo, the Philippines, &c: With which are Incorporated "The China Directory" and "The Hong Kong List for the Far East" ... Hong Kong Daily Press Office.

- Armstrong, Douglas Brawn (1920). British & colonial postage stamps: a guide to the collection and appreciation of the adhesive postal issues of the British empire. Methuen.

- Clark, Cumberland (1924). Britain overseas: the story of the foundation and development of the British Empire from 1497 to 1921. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd.

- Hall, Maxwell (1958). Labuan Story: Memoirs of a Small Island. Chung Nam.

- Baker, Michael H. (1962). North Borneo: The First Ten Years 1946–1956. Malaya Publishing House.

- Lack, Clem (1965). "Colonial Representation in the Nineteenth Century (Pro-Consuls of Empire and Some Australian Agents-General)" (PDF). University of Queensland Library.

- FitzGerald, Lawrence (1980). Lebanon to Labuan: a story of mapping by the Australian Survey Corps, World War II (1939 to 1945). J.G. Holmes Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780959497908.

- Wright, Leigh R. (1988). The Origins of British Borneo. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-213-6.

- Evans, Stephen R. (1990). Sabah (North Borneo): Under the Rising Sun Government. Tropical Press.

- Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29367-2.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2001). A Sudden Rampage: The Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia, 1941-1945. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-584-8.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- Yunos, Rozan (2008). "Loss of Labuan, a former Brunei island". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014.

- Pfennigwerth, Ian (2009). The Royal Australian Navy and MacArthur. Rosenberg. ISBN 978-1-877058-83-7.

- Gailey, Harry (2011). War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-80204-0.

- Saunders, Graham (2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2013). Post-War Borneo, 1945-1950: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-05810-5.

- Kratoska, Paul H. (2013). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-12514-0.

- Horner, David (2014). The Second World War (1): The Pacific. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0976-6.

- Grehan, John; Mace, Martin (2015). Disaster in the Far East 1940-1942. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-5305-8.

- Anak Robin, Juwita Kumala; Puyok, Arnold (2015). "The Political Participation of the Indigenous Muslim Community in Labuan during the British Administration, 1946–1963" (PDF) (in Malay and English). Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Abbottd, Jason P (2016). Offshore Finance Centres and Tax Havens: The Rise of Global Capital. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-14752-6.

- Keltie, J. Scott (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-27037-4.

- Steinberg, S. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1951. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-27080-0.

- Chandran, Esther (2017). "Discovering Labuan and loving it". The Star. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017.

- Welman, Frans (2017). Borneo Trilogy Volume 1: Sabah. Booksmango. ISBN 978-616-245-078-5.

- Labuan Corporation (1) (2017). "Peace Park (Taman Damai)". Labuan Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Labuan Corporation (2) (2017). "Surrender Point". Labuan Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

edit- Keppel, Henry; Brooke, James; WalterKeating, Kelly (1847). "The expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the suppression of piracy : with extracts from the journal of James Brooke, Esq., of Sarawak". University of California Libraries. London : Chapman and Hall. p. 347.

- Brooke, James; Mundy, Rodney George (1848). "Narrative of events in Borneo and Celebes, down to the occupation of Labuan : from the journals of James Brooke esq., rajah of Sarāwak, and governor of Labuan. Together with a narrative of the operations of H. M. S. Iris". Harvard University. London : J. Murray. p. 441.

- Motley, James; Dillwyn, Lewis Llewellyn (1855). "Contributions to the natural history of Labuan, and the adjacent coasts of Borneo". Smithsonian Libraries. London : J. Van Voorst. p. 118.

- Treacher, W. H (1891). "British Borneo: sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo". University of California Libraries. Singapore, Govt. print. dept. p. 190.