Crotalus ruber is a venomous pit viper species found in southwestern California in the United States and Baja California in Mexico. Three subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.[4]

| Red diamond rattlesnake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Viperidae |

| Genus: | Crotalus |

| Species: | C. ruber

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crotalus ruber Cope, 1892

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Description

editThis moderately large species commonly exceeds 100 cm (39 in) on the mainland. Large males may exceed 140 cm (55 in), although specimens of over 150 cm (59 in) are quite rare. The largest specimen on record measured 162 cm (64 in) (Klauber, 1937).[5]

Crotalus ruber is very similar in pattern to C. atrox, but it is distinguished by its reddish color, to which the specific name, ruber, refers. Also, the first lower labial scale on each side is transversely divided to form a pair of anterior chin shields.[6]

The dorsal scales are usually arranged in 29 rows, but may vary from 25 to 31 rows. Ventrals range from 185 to 206.[7]

Snakes found in coastal regions are longer on average than those found in desert regions.[8]

Common names

editCommon names include: red diamond rattlesnake, red rattlesnake, red diamond snake, red diamond-backed rattlesnake, red rattler, and western diamond rattlesnake.[3] The form found on Cedros Island, previously described as C. exsul, was referred to as the Cedros Island diamond rattlesnake,[9] or Cedros Island rattlesnake.[10]

Geographic range

editRed diamond rattlesnakes are found in the United States in southwestern California and southward through the Baja California peninsula, although not in the desert east of the Sierra de Juárez in northeastern Baja California. It also inhabits a number of islands in the Gulf of California, including Angel de la Guarda, Pond, San Lorenzo del Sur, San Marcos, Danzante, Monserrate and San José. Off the west coast of Baja California, it is found on Isla de Santa Margarita, which is off Baja California Sur, and (as C. exsul) on Isla de Cedros.[2] Dwelling in brush covered hillsides, a favored habitat is the small caves and clefts of reddish sandstone mesas.[11]

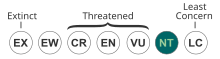

Conservation status

editThis species is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (v3.1, 2001).[12] Species are listed as such due to their wide distribution, presumed large population, or because they are unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category. The population trend was down when assessed in 2007.[13]

Habitat

editC. ruber inhabits the cooler coastal zone, over the mountains, and into the desert beyond. It prefers the dense chaparral country of the foothills, cactus patches, and boulders covered with brush, from sea level to 1,500 m in altitude.[14]

Diet

editThis species preys on rabbits, ground squirrels, birds,[14] lizards, and other snakes.[3][15] Snakes from coastal populations consume prey of larger body mass than snakes from desert populations.[16]

Reproduction

editMating occurs between February and April. Females give birth in August, to between three and 20 young. Neonates are 30 to 34 cm in length.[14]

Venom

editThis species is of a mild disposition[15] and has one of the least potent rattlesnake venoms. Nonetheless, a bite from this species is still a medical emergency and can be fatal without prompt antivenom treatment.

Brown (1973) lists an average venom yield of 364 mg (dried) and LD50 values of 4.0, 3.7 mg/kg IV, 6.0, 7.0, 6.7 mg/kg IP and 21.2 mg/kg SC for toxicity.[17]

However, Norris (2004) warned this species has a relatively large venom yield containing high levels of proteolytic enzymes, especially in the adults. A publication he mentions by Rael et al. (1986) showed it contains at least three proteolytic hemorrhagins that degrade fibrinogen and cause myonecrosis, but no Mojave toxin. On the other hand, three specimens from Mexico studied by Glen et al. (1983) did have Mojave toxin and lacked hemorrhagic activity.[18]

Bite symptoms include massive tissue swelling, pain, ecchymosis, hemorrhagic blebs, and necrosis. Systemic symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, coagulopathy, clinical bleeding and hemolysis.[18]

Subspecies

edit| Subspecies[4] | Taxon author[4] | Common name | Geographic range[2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. r. exsul[5] | Garman, 1884[5] | Cedros Island red diamond rattlesnake | Mexico, Cedros Island[9] |

| C. r. lucasensis | Van Denburgh, 1920 | San Lucan red diamond rattlesnake | Mexico, Cape region of lower Baja California |

| C. r. ruber | Cope, 1892 | Red diamond rattlesnake | The United States in southwestern California, and Mexico in Baja California, except for the Cape region of lower Baja California |

Taxonomy

editNot enough genetic and morphological diversity exists between C. exsul from Cedros Island and C. ruber from the mainland to warrant the recognition of both species.[19] Since C. exsul Garman (1884) has priority over C. ruber Cope (1892), they suggested the island population be referred to as C. e. exsul and those from the mainland as C. e. ruber. In response, Smith et al. (1998) petitioned the ICZN to validate ruber over exsul in the interest of nomenclatural stability. In 2000, the ICZN published Opinion 1960 in which they ruled C. ruber should have precedence over C. exsul.[5]

References

edit- ^ Crotalus ruber https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.100051/Crotalus_ruber

- ^ a b c McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. 1999. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, vol. 1. Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- ^ a b c Wright AH, Wright AA. 1957. Handbook of Snakes. Comstock Publishing Associates. (7th printing, 1985). 1105 pp. ISBN 0-8014-0463-0.

- ^ a b c "Crotalus ruber". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d Campbell JA, Lamar WW. 2004. The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca and London. 870 pp. 1500 plates. ISBN 0-8014-4141-2.

- ^ Schmidt, K.P. and D.D. Davis. Field Book of Snakes of the United States and Canada. G.P. Putnam's Sons. New York. 365 pp. ("Red Diamond Rattlesnake.–Crotalus ruber Cope.", pp. 299-300 & Plate 32.)

- ^ Smith, H.M. and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1982. Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Golden Press. New York. 240 pp. ("RED DIAMOND RATTLESNAKE (Crotalus ruber)", pp. 204-205.)

- ^ Eric A. Dugan and William K. Hayes (2012) Diet and Feeding Ecology of the Red Diamond Rattlesnake, Crotalus ruber (Serpentes: Viperidae). Herpetologica: June 2012, Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 203-217.

- ^ a b Klauber LM. 1997. Rattlesnakes: Their Habitats, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind. Second Edition. First published in 1956, 1972. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-21056-5.

- ^ Ditmars RL. 1933. Reptiles of the World. Revised Edition. The MacMillan Company. 329 pp. 89 plates.

- ^ Campbell, Sheldon; Shaw, Charles E. (1974). Snakes of The American West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48882-0.

- ^ Crotalus ruber at the IUCN Red List. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- ^ 2001 Categories & Criteria (version 3.1) at the IUCN Red List. Accessed 13 September 2007.

- ^ a b c Behler JL, King FW. 1979. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 743 pp. LCCCN 79-2217. ISBN 0-394-50824-6.

- ^ a b Wright and Wright (1957)

- ^ Eric A. Dugan and William K. Hayes (2012) Diet and Feeding Ecology of the Red Diamond Rattlesnake, Crotalus ruber (Serpentes: Viperidae). Herpetologica: June 2012, Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 203-217.

- ^ Brown JH. 1973. Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- ^ a b Norris R. 2004. Venom Poisoning in North American Reptiles. In Campbell JA, Lamar WW. 2004. The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca and London. 870 pp. 1500 plates. ISBN 0-8014-4141-2.

- ^ Murphy et al. (1995)

Further reading

edit- Cope ED. 1892. A critical review of the characters and variations of the snakes of North America. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 14(882): 589-694.

- Garman S. 1884. The reptiles and batrachians of North America. Memoires of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 8(3): 1-185.

- Murphy RW, Kovac V, Haddrath O, Oliver GS, Fishbein A. 1995. MtDNA gene sequence, allozyme, and morphological uniformity among red diamond rattlesnakes, Crotalus ruber and Crotalus exsul. Canadian Journal of Zoology 73(2): 270-281.

- Smith HM, Brown LE, Chiszar D, Grismer LL, Allen GS, Fishbein A, Hollingsworth BD, McGuire JA, Wallach V, Strimple P, Liner EA. 1998. Crotalus ruber Cope, 1892 (Reptilia, Serpentes): proposed precedence of the specific name over that of Crotalus exsul Garman, 1884. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 55(4): 229-232.

External links

edit- Crotalus ruber at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 12 December 2007.

- Crotalus exsul (=Crotalus ruber) Red Diamond Rattlesnake at San Diego Museum of Natural History. Accessed 7 February 2007.

- Crotalus exsul (=Crotalus ruber) Red Diamond Rattlesnake Field Observation at Laguna Beach, CA, Water Tank Road. Accessed 26 March 2022.