The Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi) is a species of bird in the nuthatch family Sittidae. It is a relatively small nuthatch, measuring about 12 cm (4.7 in) in overall length. The upperparts are bluish-grey, the underparts greyish-white. The male is distinguished from the female by its entirely black crown. The species is sedentary, territorial and not very shy. It often feeds high in Corsican pines (Pinus nigra var. corsicana, syn. P. nigra subsp. laricio), consuming mainly pine seeds, but also catching some flying insects. The breeding season takes place between April and May; the nest is placed in the trunk of an old pine, and the clutch has five to six eggs. The young fledge 22 to 24 days after hatching.

| Corsican nuthatch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sittidae |

| Genus: | Sitta |

| Species: | S. whiteheadi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sitta whiteheadi Sharpe, 1884

| |

| |

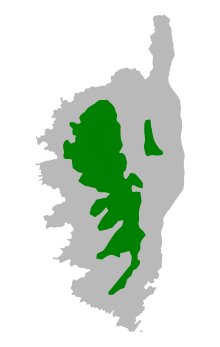

| Distribution of the Corsican nuthatch on the island, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[1] | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The Corsican nuthatch is found only on the island of Corsica, where it populates the old forests of high altitude Corsican pines, descending lower in winter. Its scientific name comes from John Whitehead, the ornithologist who brought the bird to the attention of the scientific community in 1883. The Corsican nuthatch is closely related to the Chinese nuthatch (S. villosa) and the red-breasted nuthatch (S. canadensis). It is threatened by loss of nesting sites and habitat fragmentation, with an estimated population size of about 2,000 individuals, possibly in moderate decline. Due to the small population size and the limited range, the conservation status of the Corsican nuthatch is classed as "vulnerable" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Taxonomy

editDiscovery and studies

editThe Corsican nuthatch was discovered when ornithologist John Whitehead went to observe alpine swifts (Tachymarptis melba) on 13 June 1883. Whitehead, who had spent much of the previous years in Corsica, spotted and shot a male Corsican nuthatch. He kept the specimen's skin and did not bother with it until October, when he asked Richard Bowdler Sharpe for help in naming some small birds he had collected; although the bird's head was damaged by the collection method, Sharpe assured him that the species was not yet described.[3] Whitehead thought the bird was extremely localised and did not give the precise locality where he collected the first specimens for fear that the species would be exterminated by additional collections.[4]

Whitehead returned to Corsica in May 1884 and found a male, which he recognised by its black crown. After killing it, he waited to see the accompanying female, killed it as well, and then collected three more specimens from a small flock. In the following days, he observed a pair coming and going with nesting material in a hole six meters above the ground in the trunk of a very old pine. He located other nests, some 30 m (98 ft) above the ground, and opened two of them, finding 5 eggs in each, which he collected.[3]

The Italian ornithologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli reported in 1890 that he had observed the bird on 16 September 1877 at Ponte Leccia, almost six years before Whitehead, but mistaking it for a Eurasian nuthatch (S. europaea), he did not bother to shoot it.[5] In the spring of 1896, the German naturalist Alexander Koenig visited the forest of Vizzavona and collected with great difficulty five specimens; in the early autumn of 1900, Arnold Duer Sapsworth brought back some skins. For the first, the breeding season had not begun at the time of his visit and for the second, it was over; no additional eggs were therefore brought back during this period. The next collections were made between 1908 and 1909 by the British ornithologist Francis Charles Robert Jourdain, who provided some additional field notes and explained the difficulty of accessing the nests.[4]

The first works concerning the biology of the bird were only carried out in the 1960s by the German ornithologist Hans Löhrl, who studied the reproduction, feeding and behaviour of the species. In 1976, Claude Chappuis described the voice of the species in an article dedicated to the vocalisations of birds from Corsica and the Balearic Islands.[6] In the 1980s, the Italian ornithologists Pierandrea Brichetti and Carlo Di Capi studied the reproduction of the Corsican nuthatch. Since the 1990s, the species has been studied closely by local groups, and in particular by ornithologists Jean-Claude Thibault, Pascal Villard and Jean-François Seguin.[7]: 4

In the summer of 2006, a Dutch group participating in an entomological expedition incidentally observed a pair of nuthatches in the Altai, near the meeting point of China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia, in a pure Siberian larch (Larix sibirica) forest. The male had a black crown, and the female did not, and both had a dark eyestripe topped by a white supercilium. The closest species geographically that might fit this description is the Chinese nuthatch (S. villosa), which would then be far from its known distribution, and which has more buffy underparts than the observed individuals but they were also close to Corsican nuthatch in appearance. This record could be indicative of a much wider distribution of the Chinese species, or the bird could be an as yet undescribed species related to S. whiteheadi and S. villosa.[8]

Nomenclature

editThe Corsican nuthatch was described by Sharpe in March 1884, based on the first male specimen collected by Whitehead, after who it was given the specific name. Whitehead sent a second male to Sharpe, who presented it in May to the Zoological Society of London.[9] In June, Sharpe completed the description of the species after Whitehead sent him a female.[10] The Corsican nuthatch is sometimes placed in a subgenus, Sitta subgen. Micrositta, described by the Russian ornithologist Sergei Buturlin in 1916,[11] and has no subspecies.[12]

The Corsican nuthatch was subsequently considered a subspecies of the red-breasted nuthatch (S. canadensis) from 1911 until the 1950s.[4][7]: 6–8 In 1957, American ornithologist Charles Vaurie explained that the morphology did not allow one to be sure that the Corsican nuthatch was a distinct species, and that it was probably better to consider it as belonging to the "S. canadensis" group, regrouping the species S. canadensis, S. whiteheadi and S. villosa;[13] The German ornithologist Hans Löhrl, after studying the ecology and behaviour of the birds of Latin America and Corsica, and through the publication of his field notes between 1960 and 1961, disagreed with Vaurie's position.[14][15] In 1976, the French ornithologist Jacques Vielliard described the Algerian nuthatch (S. ledanti), just discovered in Algeria by Jean-Paul Ledant. He devoted part of his article on the possible relationships of the different species and their evolutionary history. Vielliard suggests that Vaurie stopped at "a superficial morphological similarity" to bring the Corsican nuthatch closer to the red-breasted nuthatch, and that the Corsican species should rather form with Krüper's nuthatch (S. krueperi) a group known as the "Mesogean nuthatches", "where S. ledanti providentially fits in".[16]

Molecular phylogeny and evolution

editIn 1998, Eric Pasquet studied the cytochrome b of the mitochondrial DNA of a dozen nuthatch species, including the various species of the Sitta canadensis group,[17] which he defined as comprising six species, which are also those of what is sometimes treated as the subgenus Sitta subgenus Micrositta:[11] S. canadensis, S. villosa, S. yunnanensis, S. whiteheadi, S. krueperi and S. ledanti. Pasquet concludes that the Corsican nuthatch is phylogenetically related to the Chinese nuthatch and the red-breasted nuthatch, these three species forming the sister group to a clade including Krüper's nuthatch and the Algerian nuthatch. The first three species would even be close enough to constitute subspecies, rejecting Vielliard's "mesogean" theory and thus confirming Vaurie's conclusions.[17][11]: 190 For the sake of taxonomic stability, however, all retain their full species status.[7]: 6–8 In 2014, Eric Pasquet and colleagues published a phylogeny based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA of 21 nuthatch species and confirmed the relationships of the 1998 study within the "S. canadensis group", adding the Yunnan nuthatch, which was found to be the most basal of the species.[18] The study findings align with the morphology of the species, the red-breasted nuthatch, Corsican nuthatch and Chinese nuthatch sharing as a derived character the entirely black crown only present in males, a unique trait in the Sittidae and related families. The second clade, which includes Krüper's and Algerian nuthatches, has a black front crown only in males, this sexual dimorphism being absent in young individuals.[17]

The phylogeny established, Pasquet concludes that the paleogeographic history of the group would be as follows: the divergence between the two main clades of the "S. canadensis group" appears more than five million years ago, at the end of the Miocene, when the clade of S. krueperi and S. ledanti settles in the Mediterranean basin at the time of the Messinian salinity crisis; the two species constituting it diverge 1.75 million years ago. The other clade split into three with populations leaving Asia from the east, giving rise to the red-breasted nuthatch, and then from the west, about one million years ago, marking the separation between the Corsican and Chinese nuthatches.[17] Current distributions do not necessarily accurately reflect ancestral ones, however, and the Corsican nuthatch may be a paleoendemic that once had a much wider distribution and underwent reductions in distribution; "trapped" in Corsica, it would have evolved by vicariance.[7]: 6–8 [17]

The simplified cladogram below is based on the phylogenetic analysis of Packert and colleagues (2014):[18]

|

Description

editPlumage and measurements

editThe Corsican nuthatch is a small bird, measuring 11–12 cm (4.3–4.7 in) long[19] with a wingspan of 21–22 cm (8.3–8.7 in)[20] and a weight of 11–12.6 grams (0.39–0.44 oz).[21] The folded wing measures 7 cm (2.8 in), the relatively short tail measures 3.5 cm (1.4 in), and the tarsus and beak measure 1.6 cm (0.63 in).[10] The head is small and the bill is short for a nuthatch. It is thin and blackish grey, black on its tip. The eyes are black, the legs and toes are light brown.[19]

The upperparts are overall bluish grey, the belly pale greyish buff with the throat whiter. The male has a black crown and forehead, and a black eyestripe, separated from the crown by a broad, sharp white supercilium.[22] In females, the crown and eyebrow line are the same grey as the back.[19] In both sexes, the sides of the head as well as the throat are white; the underparts, overall greyish white, are more or less shaded with buff. The outer rectrices are black with white spots and grey tips.[22] The birds undergo a complete moult every year after the breeding season.[21] Sexual dimorphism appears eleven days after hatching, and fledged young have a plumage close to that of adults. As juveniles, they remain duller, with some brown on the large coverts.[22]

Vocalisations

editThe contact call is a light, whistling pu, which the bird repeats in series of five to six notes, in pupupupu.[22][23] When agitated, this nuthatch emits a "rough and stretched, slowly repeated" pchèèhr, as might a common starling (Sturnus vulgaris),[19] or a psch-psch-psch that turns into a chay-chay-chay or sch-wer, sch-wer when more agitated.[22] The song, described as a "clear, sonorous, rapid dididididi [and of] variable rhythm", meanwhile, is reminiscent of the alpine swift; the contact call is a similar trill.[19] It "sings fairly regularly in the spring", but is more discreet during the breeding season.[22]

Similar species

editThe Corsican nuthatch is the only nuthatch found in Corsica, however, it may be reminiscent of the coal tit (Parus ater), which is common in Corsican forests and has similar markings on its head.[21] The Eurasian nuthatch which inhabits nearby mainland France is larger, has no black on the crown and has yellow (or white for some subspecies) underparts tending to orange around the rump.[19] In the original description, Sharpe likened it morphologically to the Chinese nuthatch, which however has more brightly coloured underparts, and to Krüper's nuthatch, which is the same size and has the same colour upperparts, but has a reddish-brown area on the underparts that is absent in the Corsican species.[24] The Corsican nuthatch is also similar to the red-breasted nuthatch, which is found only in North America, but has yellowish underparts. Finally, the Corsican species most closely resembles the Algerian nuthatch, from Babor Mountains, which can be distinguished by its paler underparts, whitish sides of the head, and by the male's crown, which has only the black front.[19]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Corsican nuthatch is the only species of bird endemic to Corsica, and even to metropolitan France.[25] Its range covers the majority of the island, which is very mountainous. This bird is found from the Tartagine-Melaja forest in the north to the Ospedale forest in the south, but it is particularly abundant in the Monte Cinto, Monte Rotondo, Monte Renoso and Monte Incudine massifs.[22][6] There are also two isolated populations, in Castagniccia in the northeast of the island, and in the Cagna mountain in the south.[26]

The Corsican nuthatch favours Corsican pine (Pinus nigra var. corsicana) forests interspersed with clearings; their Mediterranean climate habitat is fairly dry in the summer (three weeks to two months of drought) and experiences heavy rainfall and/or snow in the winter (total 800–1,800 mm (31–71 in) per year).[7]: 9–14 This nuthatch is sedentary; it generally lives in deep valleys between 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level between April and October, but can be found from 750–1,800 m (2,460–5,910 ft), although the more open forests at higher elevations are less suitable. It descends lower in winter, and may then inhabit mixed forests of Corsican and maritime pines (Pinus pinaster)[19][22] or forests of silver fir (Abies alba); however, its stand indices are significantly lower than in pure Corsican pine forests.[7]: 15–25 It avoids hardwood-dominated or mixed woodlands.[7]: 9–14

Old pines provide the nuthatch with abundant food, and the species is absent from sectors where trees are less than 28 cm (11 in) diameter, and where the Corsican pine is in the minority compared to other species. The places most likely to hold Corsican nuthatches have large trees (over 16 m (52 ft) high) and large diameter (over 58 cm (23 in)). The preference of the bird for the Corsican pine over the maritime pine could be explained by the toughness of the seeds of the latter.[21] From a historical perspective, Thibault and colleagues explain in 2002 that "the Corsican nuthatch and the Corsican pine, probably present on the island since at least the middle of the Quaternary, had to face the last climatic fluctuations of the Pleistocene, which caused deep modifications in the composition and distribution of the vegetation. It is likely that the nuthatch survived in the Corsican pines throughout this period.[27]

Behaviour and ecology

editLike all nuthatches, the Corsican nuthatch can move head down along branches, and is rarely found on the ground. It is a territorial bird and is not shy. It lives in monogamous pairs evolving all year long on the same territory of three to ten hectares, the two birds of the couple defending it from intruders, of the same species or of another. The home range, the area where the birds generally live within their territory, varies in size, depending on the season and age of the birds, but especially on the cone production of the pines.[7]: 15–25 [21]

Food and feeding

editThe Corsican nuthatch consumes mainly pine seeds, but also small insects in summer. From March to November, small arthropods (adult insects and their larvae, spiders) represent the main part of its diet; it catches them in flight but more generally in the trees;[21] it makes a quarter of its captures in flight, from a lookout post, and exploits the rest of the time the substrates provided by the trees.[28] In spring and summer, it is more likely to be found in the treetops, foraging high up in the foliage of pine trees, at the end of branches, like a tit;[19] in autumn, however, it searches for food along the trunks and on large branches, and may also form mixed feeding flocks with other small passerines outside the breeding season.[22] November marks the beginning of the opening of pine cones, from which the Corsican nuthatch extracts seeds with its fine bill.[21] In years of high production, the nuthatch may find food resources in the cones until March. As nuthatches often do, the Corsican nuthatch hides some seeds under the bark or under lichens or plant debris, and consumes them in the off-season, especially when early spring snows prevent access to pine cones, or when cones remain closed on wet, cold days.[22][29] This use of hiding places may also partly explain the bird's complete sedentary ecology.[30]

Breeding

editMale Corsican nuthatches begin singing in late December, but the breeding season occurs in April–May. In years of high cone production, breeding occurs early; in years of low production, nuthatches must wait until insects are present in large quantities.[31] The species depends for its nesting on conifers that are two to three hundred years old with sufficiently soft trunks, dead, worm-eaten or partially struck by lightning. The Corsican nuthatch favours dead trees that still have some branches, which can be used as a singing post, as a stalking post or to monitor the surroundings, but the height of the trunk, the surrounding pine cover or the diameter of the trunk are not significant.[7]: 15–25

A 2005 study reported that the nests of different pairs were located 284–404 m (932–1,325 ft) apart depending on the year (between 1998 and 2003).[31] Both members of the pair excavate the nest, often reusing cavities excavated by great spotted woodpeckers (Dendrocopos major), but avoiding the high risk of predation from the former nests of these birds. There can be two entrances to the cavity if the trunk is particularly rotten. The entrance is 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in) wide, and the cavity averages 56 mm × 109 mm (2.2 in × 4.3 in) with an average depth of 12 cm (4.7 in).[32] The nest is placed between 2–30 m (6.6–98.4 ft) above the ground. It is made of various plant materials (pine needles, bark, and shavings) and lined with softer materials such as feathers, moss, horsehair, or lichen.[22]

The female lays in late April or early May, four to six (average 5.1)[31] oval white eggs with reddish-brown spots, especially on the broad end, with "a few faint brown or dark grey-purple markings.[22] Whitehead compares the eggs in size to those of the great tit (Parus major);[3] according to Jourdain, who compares 42 eggs (14 collected by Whitehead, the other 28 by himself), they measure on average 17.18 mm × 12.96 mm (0.68 in × 0.51 in). The average weight, calculated for 17 of these eggs, is 82.2 milligrams.[4] Brooding lasts from 14 to 17 days; it is carried out by the female alone, which the male feeds on average 3.2 times per hour. The beak and wing of the chicks grow steadily, while the tarsus stabilises by the twelfth day; the crown darkens by the eleventh day, and the young are fully plumaged after an average of twenty days.[32]

The brood usually has 3 to 6 (average 4.3) fledglings, which leave the nest at an age of 22 to 24 days.[20][31] If the first brood fails or is lost, the pair makes a second brood between 28 May and 16 June; one-third of these replacement broods are made in another tree. From one year to the next, nearly half of the pairs change trees to nest in.[31] The young may breed at one year of age. The annual survival rate has been estimated at 61.6% for males (more than three out of five individuals make it through the year);[33] life expectancy is poorly known, but colour ringing has shown that a small number of individuals can reach six years old.[21]

Threats and conservation

editNumbers and status

editAn estimate from the 1960s–1980s counted 2,000 to 3,000 pairs, spread over 240 km2 (93 sq mi), whereas in the 1950s there were nearly 3,000 pairs over 430 km2 (170 sq mi).[21][22] In 2000, Thibault and colleagues estimated the numbers at 2,075–3,010 pairs.[7]: 9–14 In 2013, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Thibault and colleagues estimate the Corsican nuthatch population at 3,100–4,400 mature individuals, or 4,600–6,600 birds in total.[1] A 2011 estimate of the range put it at 185 km2 (71 sq mi).[34] The Corsican nuthatch was considered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as "near threatened" in 1988, and "least concern" in 2004, 2008 and 2009. Since 2010, it has been considered "vulnerable",[1] with Thibault and colleagues estimating a 10% decline over the previous ten years in a 2011 paper.[34]

Threats

editThe decrease in numbers can be explained by fire and logging; the Corsican pines to which the species is attached regenerate less quickly than they otherwise disappear, and the felling of dead pines poses problems for the nesting of this nuthatch.[1][22] In addition to destroying the birds' territories, regrowth after fire may result in the replacement of Corsican pine by maritime pine or holm oak (Quercus ilex).[21] A study carried out on the consequences of the fires of the summer of 2000, which affected several large Corsican massifs, concluded that the direct consequences (disappearance of territories) and indirect consequences (difficulties in nesting and feeding in winter) could have affected 4% of the species' population.[35] For the same period in the Restonica gorges, 6 out of 12 territories were lost.[36] The major impacts of the forest fires of August 2003 also led to a decline in the population, which was reduced by 37.5% the following spring.[37]

Predators of the Corsican nuthatch include the great spotted woodpecker, which may attack nests and young birds by enlarging the nest cavity to gain access to nuthatch offspring; not all individuals necessarily attack nests, and nuthatches and woodpeckers may even nest in the same tree. The garden dormouse (Eliomys quercinus) is also a potential predator, having been observed sleeping in a nest and suspected of several losses;[31] to a lesser extent, the Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) could include the Corsican nuthatch among its prey: nuthatch remains were reported in the diet of one of these birds of prey in 1967, and Löhrl reported in 1988 that the Corsican nuthatches he raised in captivity would hide at the sight of a raptor. The Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) may also be a more or less important predator of fledglings.[7]: 25–30

The study of the habitat structure of the Corsican nuthatch has shown that the fragmentation of its habitat, which leads to a local concentration of populations, could be a new threat. Nuthatches avoid open areas and young plantations that present an increased risk of predation, only crossing them if these areas are sufficiently narrow.[7]: 34–42 A 2011 study attempted to quantify the impact of global warming on the future distribution of Corsican and maritime pines; taking only climate disruption into account, it is likely that by 2100, 98% of the Corsican nuthatch's range will still be likely to support it, and that this distribution may even expand by 10%. The bird's habitat is more threatened by the increase in frequency and severity of fires and increases in human activity in forests than by direct climate change.[38]

Protection

editThe Corsican nuthatch is fully protected on French territory by virtue of article 3 of the decree of 29 October 2009, establishing the list of protected birds on the whole territory and the modalities of their protection; it is also listed in Annex I of the European Union Birds Directive and in Annex II of the Berne Convention. It is therefore forbidden to destroy, mutilate, capture or remove it, to intentionally disturb it or naturalise it, as well as to destroy or remove eggs and nests, and to destroy, alter or degrade its environment. Whether alive or dead, it is also prohibited to transport, peddle, use, hold, sell or buy it.[39]

It is estimated that 9-11% of the individuals are located in eight of the Special Protection Areas of the Birds Directive. Less than another five percent of the estimated population is found in two managed biological reserves and six integral biological reserves.[21] In addition to fire prevention and control, specific measures are envisaged for the protection of the species, mainly focused on forestry methods and strategies: the first priority is to be given to the structure of the habitat; the second priority is given to the presence of nesting sites.[7]: 34–42

In culture

editThe Corsican nuthatch is sometimes referred to as Whitehead's nuthatch,[40] and it also has a variety of local names in the Corsican language, such as pichjarina, pichja sorda or furmicula, and capinera, used at least in Corte.[21][7]: 5–6 The species remains relatively unknown to the public. The regional natural park of Corsica has published a small comic strip on the bird, and the "Corsican ornithological group" (GOC) has chosen the species as its logo, represented in a very refined form. In the forest of Aïtone, near Évisa, the National Forestry Office has created a "nuthatch trail", which is one of the places where the species can be more easily observed.[7]: 25–30

References

edit- ^ a b c d e BirdLife International (2018). "Sitta whiteheadi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22711176A132094517. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22711176A132094517.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Dickinson, Edward C.; Loskot, Edward C.; Loskot, Vladimir M.; Morioka, Hiroyuki; Somadikarta, Soekarja (2000). "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 66. Types of the Sittidae and Certhiidae". Zoologische Mededelingen (80): 287–310.

- ^ a b c Whitehead, John (1885). "Ornithological notes from Corsica". The Ibis. 27 (1): 24–48. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1885.tb06232.x.

- ^ a b c d Jourdain, Francis Charles Robert (1911). "Notes on the Ornithology of Corsica – part II". The Ibis. 9th series. 5 (1): 440–445.

- ^ Giglioli, Enrico Hillyer (1890). Primo resoconto dei risultati della inchiesta ornitologica in Italia: Second part: Avifauna locali. Corsica. p. 636.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Brichetti, Pierandrea; Di Capi, Carlo (1987). "Conservation of the Corsican Nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi Sharpe, and proposals for habitat management". Biological Conservation. 39 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(87)90003-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Thibault, Jean-Claude; Seguin, Jean-François; Norris, Ken (2000). Restoration plan for the Corsican nuthatch. Regional Natural Park of Corsica.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ T. Smit, John; Zeegers, Theo; van den Heuvel, Esther; Roels, Bas (2007). "Unidentified nuthatch in Siberian Altay in July 2006" (PDF). Dutch Birding. 29 (3): 636.

- ^ "Summary of the session of May 20, 1884". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 52 (2): 329. May 1884.

- ^ a b Bowdler Sharpe, Richard (1884). "Conservation of the Corsican nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi Sharpe, and proposals for habitat management". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 52 (3): 414–415. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1884.tb02849.x.

- ^ a b c Matthysen, Erik (1998). The Nuthatches. Appendix I – Scientific and Common Names of Nuthatches. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-85661-101-8.

- ^ "Nuthatches, Wallcreeper, treecreepers, mockingbirds, starlings, oxpeckers – IOC World Bird List". IOC World Bird List – Version 11.2. Retrieved 26 Dec 2021.

- ^ Vaurie, Charles (1957). "Systematic Notes on Palearctic Birds. No. 29. The Subfamilies Tichodromadinae and Sittinae" (PDF). American Museum Novitates: 1–26.

- ^ Löhrl, Hans (1960). "Vergleichende Studien über Brutbiologie und Verhalten der Kleiber Sitta whiteheadi Sharpe und Sitta canadensis L.". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 101 (3): 245–264. doi:10.1007/BF01671038. S2CID 6728731.

- ^ Löhrl, Hans (1961). "Vergleichende Studien über Brutbiologie und Verhalten der Kleiber Sitta whiteheadi Sharpe und Sitta canadensis L. II. Sitta canadensis, verglichen mit Sitta whiteheadi". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 102 (2): 111–132. doi:10.1007/BF01671629.

- ^ Vielliard, Jacques (1976). "A new relict witness of speciation in the Mediterranean zone: Sitta ledanti (Aves, Sittidae)". Weekly Reports of the Sessions of the Academy of Sciences. 283: 1193–1195.

- ^ a b c d e Pasquet, Eric (1998). "Phylogeny of the nuthatches of the Sitta canadensis group and its evolutionary and biogeographic implications". The Ibis. 140 (1): 150–156. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1998.tb04553.x.

- ^ a b Pasquet, Eric; Barker, F Keith; Martens, Jochen; Tillier, Annie; Cruaud, Corinne & Cibois, Alice (2014). "Evolution within the nuthatches (Sittidae: Aves, Passeriformes): molecular phylogeny, biogeography, and ecological perspectives". Journal of Ornithology. 155 (3): 755. doi:10.1007/s10336-014-1063-7. S2CID 17637707.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Svensson, L., Mullarney, K., & Zetterström, D. (2022) Collins Bird Guide, ed. 3. ISBN 978-0-00-854746-2, pages 362-363

- ^ a b Corsican Nuthatch. European Birdguide Online. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Birds Habitat Notebook – Corsican Nuthatch, Sitta whiteheadi (Sharpe, 1884)" (PDF). National Inventory of Natural Heritage. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sitta whiteheadi. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Harrap, Simon (1996). Christopher Helm (ed.). Tits, Nuthatches and Treecreepers. Illustrated by David Quinn. Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-3964-4.

- ^ Bowdler Sharpe, Richard (1884). "On an apparently new Species of European Nuthatch". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 52 (2): 233. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1884.tb02826.x.

- ^ Morin, Jérôme; Guillot, Gérard; Norwood, Julien (2017). The guide to the birds of France. Humensis. ISBN 9782410012149.

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude; Bonaccorsi, Gilles (1999). The Birds of Corsica: An annotated checklist. BOU Checklist Number 17. Tring, Herts. UK: British Ornithologists' Union. ISBN 0-907446-21-3.

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude; Seguin, Jean-Francois; Villard, Pascal; Prodon, Roger (2002). "Le pin Laricio (Pinus nigra laricio) est-il une espèce clé pour la Sittelle Corse (Sitta whiteheadi)" (PDF). Revue d'écologie. 57 (3–4): 329–341. doi:10.3406/revec.2002.2399. S2CID 127622180.

- ^ Villard, Pascal; Bichelberger, S.; Seguin, Jean-François; Thibault, Jean-Claude (2003). "The quest for food of the Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi) in the Corsican pines (Pinus nigra laricio)". Vie et Milieu. 53 (1): 27–32.

- ^ Moneglia, Pasquale (2003). Study on the fruiting of the Corsican pine (Pinus nigra laricio) as a winter food resource for the Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi): Memory of DEA Sciences for the Environment Biodiversity (Report). University of Corsica.

- ^ Thibault, Jean Claude; Prodon, Roger; Villard, Pascal; Seguin, Jean-Francois (2006). "Habitat requirements and foraging behaviour of the Corsican nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi". Journal of Avian Biology. 37 (5): 477–486. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2006.03645.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Thibault, Jean-Claude; Villard, Pascal (2005). "Reproductive ecology of the Corsican Nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi: capsule food availability determines date of clutch initiation, and predation is the main cause of clutch failure". Bird Study. 52 (3): 282–288. doi:10.1080/00063650509461401. S2CID 88027746.

- ^ a b Villard, Pascal; Thibault, Jean-Claude (2001). "Data on nests, chick growth and parental care in the Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi)". Alauda. 69: 465–474.

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude; Jenouvrier, Stéphanie (2006). "Annual survival rates of adult male Corsican nuthatches Sitta whiteheadi" (PDF). Ringing & Migration. 9. 23 (1): 85–88. doi:10.1080/03078698.2006.9674349. S2CID 85182636. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ a b Thibault, Jean-Claude; Hacquemand, Didier; Moneglia, Pasquale; Pellegrini, Hervé; Prodon, Roger; Recorbet, Bernard; Seguin, Jean-François & Villard, Pascal (2011). "Distribution and population size of the Corsican Nuthatch Sitta whiteheadi". Bird Conservation International. 21 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1017/S0959270910000468. S2CID 85727767.

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude; Prodon, Roger; Moneglia, Pasquale (2004). "Estimation of the impact of fires in the summer of 2000 on the population of a threatened endemic bird: the Corsican nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi)". Ecologia Mediterranea. 30 (2): 195–203. doi:10.3406/ecmed.2004.1459.

- ^ Thibault, Jean-Claude; Beck, Nicolas; Moneglia, Pasquale (2002). "The consequences of the summer 2000 fire on the population of the Corsican Nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi) in the Restonica Valley, Corsica". Alauda. 70 (4): 431–436.

- ^ Moneglia, Pasquale; Besnard, Aurélien; Thibault, Jean-Claude; Prodon, Roger (2009). "Habitat selection of the Corsican Nuthatch (Sitta whiteheadi) after a fire". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (3): 577–583. doi:10.1007/s10336-009-0379-1. S2CID 46106724 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Barbet-Massin, Morgane; Jiguet, Frédéric (2011). "Back from a predicted climatic extinction of an island endemic: a future for the Corsican nuthatch". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): 577–583. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618228B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018228. PMC 3064676. PMID 21464916.

- ^ Ministry of Ecology, Energy, Sustainable Development and the Sea, responsible for green technologies and climate negotiations (5 December 2009). "Order of 29 October 2009 setting the list of protected birds on all of the territory and the methods of their protection". Official Journal of the French Republic.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paris, Paul (1921). "Faune de France 2 Oiseaux". Fauna of France, Birds. French Federation of Science Societies.

External links

edit- Sitta whiteheadi - Avibase