This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (August 2023) |

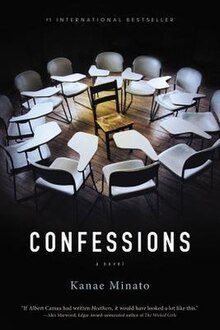

Confessions is Stephen Snyder's 2014 translation of Kanae Minato's 2008 debut novel, Kokuhaku. It is a suspense novel that traces the impact of a schoolteacher's act of revenge, and it deals with themes of motherhood and power as well as social issues like AIDS and hikikomori. The novel's chapters are in the form of a one-sided conversation, a letter, a diary entry, a reminiscion, a blog post, and a one-sided phone call. The novel was also adapted into a 2010 Japanese feature film of the same name; Minato has received many awards for her debut work.

| |

| Author | Kanae Minato |

|---|---|

| Translator | Stephen Snyder |

| Language | Japanese (translated to English) |

| Genre | Mystery/Thriller |

Publication date | August 5, 2008 (Original) August 19, 2014 (Translation) |

| Publication place | Japan |

| Awards | Shosetsu Suiri New Writers Prize (2007; for the first chapter) Japanese Booksellers Award (2009) Alex Award (2015) Nominee for Strand Critics Award for Best First Novel (2015) Nominee for Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel (2015) |

Plot

editA middle school teacher named Yuko Moriguchi brings her students together and announces her retirement due to the death of her young daughter, Manami.[1] The police concluded the drowning was accidental, but Moriguchi reveals that Manami was actually murdered by two students in the class, dubbing them "A" and "B". Through interrogations, Moriguchi finds out that A and B approached Manami after school and knocked her unconscious with a shock purse[clarification needed] A made. Thinking she died, B attempted to cover up the murder by putting Manami's body in the pool where she drowned. Moriguchi decided not to trust the law for punishment but instead mixed HIV-positive blood from Manami's father into A and B's milk cartons in an attempt to infect them.[1]

The class president of Moriguchi's former class, Mizuki, writes a letter to her to tell her what has happened since her retirement.[2] Naoki Shitamura (B) did not show up to school, whereas Shuya Watanabe (A) acted as if nothing had changed. Their new teacher, Werther, enlisted Mizuki's help to visit Naoki and encourage him to come back.[2] His mother became less accepting of Werther and Mizuki’s visits over time. Werther found out Shuya was being bullied, and Mizuki's classmates forced her to participate, believing she snitched.[2] Mizuki later revealed to Shuya that after the day of Moriguchi's confession, she had tested the milk cartons to find that there had not been blood in them, which Shuya had confirmed with his own blood test. He then weaponized his fake illness to end the bullying. The two then began a relationship. Shortly after Werther and Mizuki’s last visit to Naoki’s house, Naoki killed his mother.[2]

Naoki's older sister learns of her mother's death and reads her diary in an attempt to figure out what happened.[2] In it, Mrs. Shitamura wrote her thoughts about the events. She explains that Naoki had become obsessed with cleanliness while neglecting his own hygiene and becoming reclusive. These behaviors worsened, and he cut off most contact with his mother. In response to his filth, Mrs. Shitamura cut his hair while he was asleep. Soon after this, Naoki bathed, shaved his head, and went to the store by himself. Mrs. Shitamura later received a call from the manager of the store, who told her Naoki had smeared blood over many items in the store. Naoki claimed he wanted to get arrested, and revealed to her what happened on the day of Moriguchi's confession. He also told her that Manami had opened her eyes before he dropped her into the pool. After Werther and Mizuki's final visit, Mrs. Shitamura resolved to kill herself and her son.[2] Naoki's sister believes that Naoki will be found innocent after she gives the diary to the police.

Naoki then gives his perspective on the story.[2] At the start, he was approached by Shuya, and they began to hang out. Shuya brought up his shock purse, asking Naoki if he wanted to punish someone. Naoki picked Manami. After they tricked Manami and she collapsed, Shuya told Naoki to spread the word about the murder and called Naoki a failure. When Manami regained consciousness, Naoki realized that he had the chance to succeed where Shuya failed and drowned her. After Moriguchi's confession, Naoki feared death and infecting his family with HIV. He became reclusive and fearful of Werther and Mizuki's visits, believing Werther to be in league with Moriguchi. One day, Naoki noticed his filth and took it as proof of being alive. That night, his mother cut his hair. This upset Naoki, and he decided to rid himself of evidence of his life – his filth and hair. He then caused the incident at the store, hoping to get arrested. His mother then attempted to kill him.[2] Naoki accepted this until she mentioned her failure, after which he stabbed her, and she fell down the stairs.

Shuya presents his perspective through a last will and testament posted to his website. He explains that his mother was abusive to him, leading to his father divorcing her.[2] Hoping to reconnect with his mother, Shuya started his website and began trying to draw his mother’s attention through his inventions, eventually submitting his shock purse to the national science fair. His success was overshadowed by a case of a child murdering her family, leading him to want to commit a horrible act for attention. He approached Naoki only for the purpose of choosing a victim. After the murder and Moriguchi’s confession, Shuya was happy to learn that he may have contracted HIV, as he felt it could reconnect him with his mother. Months later, he was unhappy to test negative. After this and the bullying incidents, Mizuki began seeing him regularly. One day, Shuya and Mizuki got into an argument, resulting in Shuya killing Mizuki.[2] Three days before writing his will and testament, Shuya attempted to find his mother where she worked. There, he learned that she had remarried and was pregnant.[2] Shuya decided to commit mass murder and suicide as revenge against his mother by detonating a bomb during an all-school assembly the next day.[2] Rather than the bomb detonating, Shuya receives a phone call from Moriguchi.

Moriguchi explains to Shuya that she read his post. She reveals that she did put blood in their milk, but Manami's father found out about her plan and replaced the cartons.[2] Moriguchi, upon meeting Terada, learned what had gone on with the class. Without telling Terada that she was his predecessor, she gave him advice in order to make things worse for Naoki and Shuya. Upon learning about Mrs. Shitamura's death, Moriguchi felt like her revenge against Naoki was complete. In order to complete her revenge on Shuya, she began to check his website regularly for information. After hearing about Shuya's plan, Moriguchi relocated the bomb to his mother’s university.[2] Moriguchi explains that by making Shuya kill his own mother, she has completed her revenge, and tells Shuya that he can begin his road to recovery.

Characters

edit| Name | Role | Chapters |

|---|---|---|

| Yuko Moriguchi | Schoolteacher and Manami's mother | Narrator of chapters one and six[2] |

| Manami Moriguchi | Ms. Moriguchi's four-year-old daughter | |

| Masayoshi "Saint" Sakuranomi[3] | Famous retired schoolteacher, AIDS patient, and Manami's father | |

| Mizuki Kitahara | Class president and brief girlfriend of Shuya | Narrator of chapter two[2] |

| Yuko Shitamura[3] | Naoki's sister and mother | Narrator of chapter three[2] |

| Naoki Shitamura | Student of Ms. Moriguchi and Werther, murderer | Narrator of chapter four[2] |

| Shuya Watanabe | Student of Ms. Moriguchi and Werther, murderer, brief boyfriend of Mizuki | Narrator of chapter five[2] |

| Terada "Werther" Yoshiteru[3] | Replacement teacher for Ms. Moriguchi |

Themes

editMilk, motherhood, and power

editOne of the groups of themes critics and analysts interpreted from the novel is milk, motherhood, and power. Throughout the novel, Minato highlights different mother-child relationships, some of which are what motivate Manami's murderers. Moriguchi and the other teachers in the school hand out milk cartons to their homeroom classes every morning as part of a case study.[4] However, she inserts HIV-positive blood into those that Shuya and Naoki drink as an act of revenge for killing her daughter. The milk, a symbol of motherhood, represents the impact mothers have on their children as mothers use bottle feeding or breastfeeding to nourish their child.[4]

Since the milk cartons have infected blood, the motherly role of supporting developing children is flipped to neglect. The purpose of the milk is misused and points at Shuya and Naoki's maternal figures.[4] Shuya perceived that his mother was taking her displeasure for his life out on him through various retributions, such as domestic violence through hitting him. Shuya then no longer saw his worth because of the power and influence his mother had over him. This struggle between the two even led to Shuya appreciating the punishments his classmates inflicted upon him.[5] It was this love and infatuation he had with the image of his mother that led him to see her abuse as justified. The murders he committed were then equally justified in his eyes because his view on the value of life was significantly diminished.[5]

Naoki was raised differently than Shuya in that his mother emphasized "self-surveillance".[5] Naoki learned to be self-conscious because his mother was the same way. She worried about others' perceptions of her and wanted to have Naoki be seen as "normal" in society's sense. In order to meet this standard, self-inflicted punishment followed after his classmates actively ignored him, and he became worried about dying from HIV. Naoki became paranoid about this perceived impending death from AIDS, which led him to isolate even more.[5]

AIDS

editAnother theme pulled was involving AIDS. Ms. Moriguchi attempts to punish Naoki and Shuya by injecting milk cartons the students were to drink with HIV-positive blood. This act's consequences go beyond health risks. Naoki becomes obsessed with the possibility of being sick, and this anxiety causes him to become a recluse.[5] Shuya also becomes obsessed with the possibility of being sick, but he is glad for it. The infection rate through this transaction, however, is extremely low. Considering that the blood was not injected into the bloodstream directly, the transmission rate for AIDS would be considered "negligible", likely to fall under the "throwing bodily fluids" category on the CDC's site for transmission rates.[6]

Hikikomori

editThis section possibly contains original research. (May 2024) |

Hikikomori is another theme analysts discussed. In the novel, Naoki is considered a hikikomori by both his mother and sister because of his severe reclusion from the outside world and his family. It is attributed to his belief that he might have contracted AIDS, and he stays away from everyone to keep the spread diminished.

Hikikomori is a Japanese social condition that is characterized by a severe seclusion of oneself from social situations for anywhere from months to years. The word "hikikomori" is the same for either the person suffering or the action of withdrawal. In Japanese culture, it's generally acceptable terminology. It is often used in place of other specific diagnostic terms.[7] It is not a very widespread phenomenon. This disorder is usually found in people in adolescence or their early twenties.[7]

Naoki develops all five criteria the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare list that must be met for a diagnosis of hikikomori: "a lifestyle centered at home", "no interest or willingness to attend school or work", "symptom duration of at least six months", "schizophrenia, mental retardation, or other mental disorders have been excluded", and "no interest or willingness to attend school or work" alongside a neglect of personal relationships.[7]

Hikikomori is difficult to diagnose because it is often found alongside other mental disorders. All patients able to present themselves for psychiatric care in one study had other conditions, including schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, eating disorders, and others.[7] This phenomenon is seen in Confessions, when Naoki's mother blames her son's seclusion and strange behavior on obsessive-compulsive disorder. This misunderstanding creates issues between the two as the plot develops.

Juvenile punishment

editThis section possibly contains original research. (May 2024) |

Juvenile punishment was also prevalent in the novel. Moriguchi does not report her students because she does not believe the juvenile system will be effective at punishing them. A study conducted on the change to the Japanese Juvenile Law, where children from the age of 14-15 can now be punished for serious crimes, shows that subjecting students in junior high to punishment for their crime reduces arrests. Although 13-year-olds are not subject to criminal punishment under the new law, the arrest rates were reduced between 7 and 20 percent. 14-year-old arrests dropped between 5 and 15 percent while 15-year-olds dropped between 6 and 10 percent. [8] The study contributes the possibility of these changes to social interactions that unpunishable ages now have with age groups that can be subject to juvenile justice. Before, 14- to 15-year-olds could not be punished, but their recent exposure to punishment could have discouraged them from participating in crimes.[8]

Critical response

editThe Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center called Confessions "one of the most horrifyingly gripping novels" they'd ever read,[1] while writer Tom Nolan at The Wall Street Journal reflected on Minato's social commentary, saying that "[f]rom these composite testimonies emerges a sketch of a society where adults are too busy or insensitive to attend to children's needs, and children too alienated to find proper social and moral bearings."[9] Confessions was included in the Wall Street Journal’s Best Books of 2014 as well, taking its place among the best in the mystery genre.[10]

Steph Cha of the Los Angeles Times described Confessions as "a nauseating tale of morality and justice, with violent turns that will drop your jaw right to the floor",[11] and Confessions was referred to as "a creepy and mesmerizing psychological thriller that challenges the conventions of right vs. wrong." by Library Journal contributor Jennifer Funk.[12]

Laura Eggertson of the Toronto Star offers a critical analysis of Minato’s characters and plot, saying that "although she does not make her main characters likeable, Minato succeeds in making their lack of remorse both chilling and believable.”[13]

Awards and nominations

edit| Year | Award / festival | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Hanya Taisho (Japan Booksellers Award)[14] | Winner |

| Year | Award / festival | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Strand Critics Award for Best First Novel[15] | Nominee |

| 2014 | Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel[16] | Nominee |

| 2015 | Alex Award[17] | Winner |

Film adaptation

editIn 2010, Confessions was adapted into a film in Japan. Tetsuya Nakashima wrote the screenplay and directed the psychological thriller. Box office revenues eventually reached ¥3.85 billion ($2,967,178)[18] in Japan alone, making it Japan's tenth highest-grossing film in 2010.[19] After being screened in other countries, the worldwide gross revenue of Confessions was a total of $45,203,103.[18] The film was generally well-received by critics and eventually won several awards, including the 34th Japan Academy Prize for Best Picture, as well as Best Picture at the 53rd Blue Ribbon Awards[20] and Best Asian Film at the 30th Hong Kong Film Awards.[21] Confessions also made the January shortlist for Best Foreign Language Film in the 83rd Academy Awards.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b c "BookDragon | Confessions by Kanae Minato, translated by Stephen Snyder". Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Lynn, Matt (2017-02-15). "Review of Kanae Minato's novel Confessions". Matt Lynn Digital. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- ^ a b c Confessions (2010) - IMDb, retrieved 2023-04-10

- ^ a b c Sipahimalani, Tarini (2018-03-23). "Minato's Novel Confessions Explores Motherhood And Revenge". The Student Life. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ a b c d e Sejahterawati, Ninna febrianna. "An Analysis of Power Relations in Kanae Minato's Novel Confessions" (2008). (2019).

- ^ "HIV Risk Behaviors | HIV Risk and Prevention Estimates | HIV Risk and Prevention | HIV/AIDS". US Centers for Disease Control. 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ a b c d Teo, Alan Robert; Gaw, Albert C. (June 2010). "Hikikomori, A Japanese Culture-Bound Syndrome of Social Withdrawal? A Proposal for DSM-V". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 198 (6): 444–449. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e086b1. ISSN 0022-3018. PMC 4912003. PMID 20531124.

- ^ a b Oka, Tatsushi (2009-11-01). "Juvenile crime and punishment: evidence from Japan". Applied Economics. 41 (24): 3103–3115. doi:10.1080/00036840701365923. ISSN 0003-6846. S2CID 154423017.

- ^ Nolan, Tom. "Book Review: Confessions by Kanae Minato". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ Graphics, WSJ com News. "Best Books of 2014: A Compilation". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ Cha, Steph (2014-08-08). "Review: Kanae Minato's Confessions hits its mark with a vengeance". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ Funk, Jennifer (June 1, 2014). "Review of Confessions". Library Journal: 90 – via Gale.

- ^ "Confessions by Kanae Minato: Review". Toronto Star. 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Book awards: Japan Booksellers | LibraryThing". LibraryThing. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Staff, Strand (2015-03-26). "Strand Critics Award Nominees 2014". The Strand Magazine. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ "The Shirley Jackson Awards » 2014 Shirley Jackson Awards Winners". Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ "Confessions | Awards & Grants". American Library Association. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ a b "Confessions". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ "Japanese Box Office For 2010". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ "Blue Ribbon Awards Best Film". IMDb. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ "Table 2: IMDB results". doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.252/table-2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hendrix, Grady (2011-01-24). "Tetsuya Nakashima's Confessions: Japan's Oscar shortlist film showcases the darkest and most intense director working today". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-12.