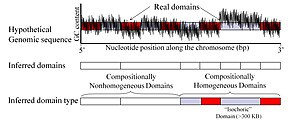

A compositional domain in genetics is a region of DNA with a distinct guanine (G) and cytosine (C) G-C and C-G content (collectively GC content).[1] The homogeneity of compositional domains is compared to that of the chromosome on which they reside. As such, compositional domains can be homogeneous or nonhomogeneous domains. Compositionally homogeneous domains that are sufficiently long (= 300 kb) are termed isochores or isochoric domains.

The compositional domain model was proposed as an alternative to the isochoric model. The isochore model was proposed by Bernardi and colleagues to explain the observed non-uniformity of genomic fragments in the genome.[2] However, recent sequencing of complete genomic data refuted the isochoric model. Its main predictions were:

- GC content of the third codon position (GC3) of protein coding genes is correlated with the GC content of the isochores embedding the corresponding genes.[3] This prediction was found to be incorrect. GC3 could not predict the GC content of nearby sequences.[4][5]

- The genome organization of warm-blooded vertebrates is a mosaic of isochores.[6] This prediction was rejected by many studies that used the complete human genome data.[1][7][8][9]

- The genome organization of cold-blooded vertebrates is characterized by low GC content levels and lower compositional heterogeneity.[10][11][12] This prediction was disproved by finding high and low GC content domains in fish genomes.[13]

The compositional domain model describes the genome as a mosaic of short and long homogeneous and nonhomogeneous domains. The composition and organization of the domains were shaped by different evolutionary processes that either fused or broke down the domains. This genomic organization model was confirmed in many new genomic studies of cow,[14] honeybee,[15] sea urchin,[16] body louse,[17] Nasonia,[18] beetle,[19] and ant genomes.[20][21][22] The human genome was described as consisting of a mixture of compositionally nonhomogeneous domains with numerous short compositionally homogeneous domains and relatively few long ones.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c Elhaik, Eran; Graur, Dan; Josić, Krešimir; Landan, Giddy (2010). "Identifying compositionally homogeneous and nonhomogeneous domains within the human genome using a novel segmentation algorithm". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (15): e158. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq532. PMC 2926622. PMID 20571085.

- ^ Bernardi, G; Olofsson, B; Filipski, J; Zerial, M; Salinas, J; Cuny, G; Meunier-Rotival, M; Rodier, F (1985). "The mosaic genome of warm-blooded vertebrates". Science. 228 (4702): 953–8. Bibcode:1985Sci...228..953B. doi:10.1126/science.4001930. PMID 4001930.

- ^ Bernardi, Giorgio (2001). "Misunderstandings about isochores. Part 1". Gene. 276 (1–2): 3–13. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00644-8. PMID 11591466.

- ^ Elhaik, E.; Landan, G.; Graur, D. (2009). "Can GC Content at Third-Codon Positions Be Used as a Proxy for Isochore Composition?". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (8): 1829–33. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp100. PMID 19443854.

- ^ Tatarinova, Tatiana V; Alexandrov, Nickolai N; Bouck, John B; Feldmann, Kenneth A (2010). "GC3 biology in corn, rice, sorghum and other grasses". BMC Genomics. 11: 308. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-308. PMC 2895627. PMID 20470436.

- ^ Bernardi, Giorgio (2000). "The compositional evolution of vertebrate genomes". Gene. 259 (1–2): 31–43. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00441-8. PMID 11163959.

- ^ Lander, Eric S.; Linton, Lauren M.; Birren, Bruce; Nusbaum, Chad; Zody, Michael C.; Baldwin, Jennifer; Devon, Keri; Dewar, Ken; et al. (2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..860L. doi:10.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011.

- ^ Belle, Elise M. S.; Duret, Laurent; Galtier, Nicolas; Eyre-Walker, Adam (2004). "The Decline of Isochores in Mammals: An Assessment of the GC ContentVariation Along the Mammalian Phylogeny". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 58 (6): 653–60. Bibcode:2004JMolE..58..653B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.333.2159. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-2587-x. PMID 15461422. S2CID 18281444.

- ^ Cohen, N.; Dagan, T; Stone, L; Graur, D (2005). "GC Composition of the Human Genome: In Search of Isochores". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (5): 1260–72. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi115. PMID 15728737.

- ^ Bernardi, Giorgio (2000). "Isochores and the evolutionary genomics of vertebrates". Gene. 241 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00485-0. PMID 10607893.

- ^ Hamada, Kazuo; Horiike, Tokumasa; Ota, Hidetoshi; Mizuno, Keiko; Shinozawa, Takao (2003). "Presence of isochore structures in reptile genomes suggested by the relationship between GC contents of intron regions and those of coding regions". Genes & Genetic Systems. 78 (2): 195–8. doi:10.1266/ggs.78.195. PMID 12773820.

- ^ Chojnowski, J. L.; Braun, E. L. (2008). "Turtle isochore structure is intermediate between amphibians and other amniotes". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 48 (4): 454–62. doi:10.1093/icb/icn062. PMID 21669806.

- ^ Costantini, Maria; Clay, Oliver; Federico, Concetta; Saccone, Salvatore; Auletta, Fabio; Bernardi, Giorgio (2006). "Human chromosomal bands: Nested structure, high-definition map and molecular basis". Chromosoma. 116 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1007/s00412-006-0078-0. PMID 17072634. S2CID 22571376.

- ^ Elsik, C. G.; Tellam, R. L.; Worley, K. C.; Gibbs, R. A.; Muzny, D. M.; Weinstock, G. M.; Adelson, D. L.; Eichler, E. E.; et al. (2009). "The Genome Sequence of Taurine Cattle: A Window to Ruminant Biology and Evolution". Science. 324 (5926): 522–8. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..522A. doi:10.1126/science.1169588. PMC 2943200. PMID 19390049.

- ^ Weinstock, George M.; Robinson, Gene E.; Gibbs, Richard A.; Weinstock, George M.; Weinstock, George M.; Robinson, Gene E.; Worley, Kim C.; Evans, Jay D.; et al. (2006). "Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera". Nature. 443 (7114): 931–49. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..931T. doi:10.1038/nature05260. PMC 2048586. PMID 17073008.

- ^ Sodergren, E.; Weinstock, G. M.; Davidson, E. H; Cameron, R. A.; Gibbs, R. A.; Angerer, R. C.; Angerer, L. M.; Arnone, M. I.; et al. (2006). "The Genome of the Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus". Science. 314 (5801): 941–52. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..941S. doi:10.1126/science.1133609. PMC 3159423. PMID 17095691.

- ^ Kirkness, Ewen F.; Haas, Brian J.; Sun, Weilin; Braig, Henk R.; Perotti, M. Alejandra; Clark, John M.; Lee, Si Hyeock; Robertson, Hugh M.; et al. (2010). "Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (27): 12168–73. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10712168K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003379107. PMC 2901460. PMID 20566863.

- ^ Werren, J. H.; Richards, S.; Desjardins, C. A.; Niehuis, O.; Gadau, J.; Colbourne, J. K.; Beukeboom, L. W.; Desplan, C.; et al. (2010). "Functional and Evolutionary Insights from the Genomes of Three Parasitoid Nasonia Species". Science. 327 (5963): 343–8. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..343.. doi:10.1126/science.1178028. PMC 2849982. PMID 20075255.

- ^ Richards, Stephen; Gibbs, Richard A.; Weinstock, George M.; Brown, Susan J.; Denell, Robin; Beeman, Richard W.; Gibbs, Richard; Beeman, Richard W.; et al. (2008). "The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum". Nature. 452 (7190): 949–55. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..949R. doi:10.1038/nature06784. PMID 18362917.

- ^ Smith, Christopher D.; Zimin, Aleksey; Holt, Carson; Abouheif, Ehab; Benton, Richard; Cash, Elizabeth; Croset, Vincent; Currie, Cameron R.; et al. (2011). "Draft genome of the globally widespread and invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (14): 5673–8. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5673S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008617108. PMC 3078359. PMID 21282631.

- ^ Smith, Chris R.; Smith, Christopher D.; Robertson, Hugh M.; Helmkampf, Martin; Zimin, Aleksey; Yandell, Mark; Holt, Carson; Hu, Hao; et al. (2011). "Draft genome of the red harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (14): 5667–72. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5667S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007901108. PMC 3078412. PMID 21282651.

- ^ Suen, Garret; Teiling, Clotilde; Li, Lewyn; Holt, Carson; Abouheif, Ehab; Bornberg-Bauer, Erich; Bouffard, Pascal; Caldera, Eric J.; et al. (2011). Copenhaver, Gregory (ed.). "The Genome Sequence of the Leaf-Cutter Ant Atta cephalotes Reveals Insights into Its Obligate Symbiotic Lifestyle". PLOS Genetics. 7 (2): e1002007. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002007. PMC 3037820. PMID 21347285.

External links

edit- IsoPlotter — a free, open source program to calculate and visualize isochores in a given genome