This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

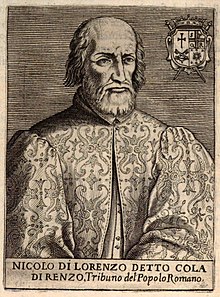

Nicola Gabrini[1] (1313 – 8 October 1354), commonly known as Cola di Rienzo (Italian pronunciation: [ˈkɔːla di ˈrjɛntso]) or Rienzi, was an Italian politician and leader, who styled himself as the "tribune of the Roman people".

Cola di Rienzo | |

|---|---|

Cola di Rienzo (1646) | |

| Senator of Rome (De facto ruler of Rome) | |

| In office 7 September 1354 – 8 October 1354 | |

| Appointed by | Pope Innocent VI |

| Rector of Rome (De facto ruler of Rome) | |

| In office 26 June 1347 – 15 December 1347 | |

| Appointed by | Pope Clement VI |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nicola Gabrini (son of Lorenzo) 1313 Rome, Papal States |

| Died | 8 October 1354 (aged c. 41) Rome, Papal States |

| Political party | Guelph (Pro-Papacy) |

| Profession | |

During his lifetime, he advocated for the unification of Italy. This led to Cola's re-emergence in the 19th century as an iconic figure among leaders of liberal nationalism, who adopted him as a precursor of the 19th-century Risorgimento.

Biography

editEarly life and career

editNicola was born in Rome of humble origins. He claimed to be the natural child of Henry VII, the Holy Roman Emperor, but he was, in fact, born to a washer-woman and a tavern-keeper named Lorenzo Gabrini. Nicola's father's forename was shortened to Rienzo, and his name was shortened to Cola; hence, Cola di Rienzo, or Rienzi, by which he is generally known.[2]

He spent his early years at Anagni, where he devoted much of his time to the study of Latin writers, historians, orators and poets. After having nourished his mind with stories of the glories and the power of ancient Rome, he turned his thoughts to restoring his native city. Knowing Rome was suffering from degradation and wretchedness, Cola sought to restore the city to not only good order but to pristine greatness. His zeal for this work was quickened by the desire to avenge his brother, who had been killed by a noble.[2]

He became a notary[3] and a person of some importance in the city, and was sent in 1343 on a public errand to Pope Clement VI at Avignon. He discharged his duties with ability and success. Although he boldly denounced the aristocratic rulers of Rome, he won the favour and esteem of the Pope, who gave him an official position at his court.[2]

Leader of revolt

editAfter returning to Rome in April 1344, Cola worked for three years at the great object of his life, the restoration of the city to its former position of power. He gathered a band of supporters, plans were drawn up, and at length, all was ready for the insurrection.[2]

On 19 May 1347, heralds invited the people to a parliament on the Capitol and on 20 May, Whit-Sunday, the meeting took place. Dressed in full armour and attended by the papal vicar, Cola headed a procession to the Capitol, where he addressed the assembled crowd, speaking "with fascinating eloquence of the servitude and redemption of Rome."[4] A new series of laws was published and accepted with acclaim, and unlimited authority and power was given to the author of the revolution.[2]

Without striking a blow the nobles left the city or went into hiding, and a few days later Rienzo took the title of tribune.[3] He called himself "Nicholaus, severus et clemens, libertatis, pacis justiciaeque tribunus, et sacræ Romanæ Reipublicæ liberator," or "Nicholas, severe and clement, tribune of liberty, peace and justice, and liberator of the Holy Roman Republic."[2]

Tribune of Rome

editCola governed the city with a stern justice, which was in marked contrast to the previous reign of license and disorder. As a result of his leadership, the tribune was received at St. Peter's with the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, while in a letter, the poet Petrarch urged him to continue his great and noble work, and congratulated him on his past achievements, calling him the new Camillus, Brutus and Romulus.[2] All the nobles submitted, though with great reluctance; the roads were cleared of robbers; some severe examples of justice intimidated offenders, and the tribune was regarded by many as the destined restorer of Rome and Italy.[citation needed]

Attempt to unify Italy

editIn July, in a decree, he proclaimed the sovereignty of the Roman people over the empire. But before this he had set to work on restoring the authority of Rome over the cities and provinces of Italy, of making the city again caput mundi. He wrote letters to the cities of Italy, asking them to send representatives to an assembly which would meet on 1 August, when the formation of a great federation under the headship of Rome would be considered. On the appointed day, a number of representatives appeared, and Cola issued an edict citing Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor and his rival Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, and also the imperial electors and all others concerned in the dispute, to appear before him in order that he might pronounce judgment.[2]The following day, the festival of the unity of Italy was celebrated, but neither this nor the previous meeting had any practical result. Cola's power, however, was recognized in the Kingdom of Naples, and both Joan I of Naples and Louis I of Hungary appealed to him for protection and aid, and on 15 August with great pomp he was crowned Tribune. Ferdinand Gregorovius says this ceremony "was the fantastic caricature in which ended the imperium of Charles the Great. A world where political action was represented in such guise was ripe for overthrow, or could only be saved by a great mental reformation."[2]

End of rule

editHe then seized, but soon released Stefano Colonna and some other barons who had spoken disparagingly of him, but his power was already beginning to wane.[2]

Cola di Rienzo's character has been described as a combination of knowledge, eloquence, and enthusiasm for ideal excellence, with vanity, inexperience of mankind, unsteadiness, and physical timidity. As these latter qualities became conspicuous, they eclipsed his virtues and caused his benefits to be forgotten.[citation needed] His extravagant pretensions only served to excite ridicule. His government was costly, and to meet its many expenses he was obliged to lay heavy taxes upon the people. He offended the Pope by his arrogance and pride, and both the Pope and Emperor by his proposal to set up a new Roman Empire, the sovereignty of which would rest directly upon the will of the people. In October, Clement gave power to a legate to depose him and bring him to trial, and the end was obviously in sight.[2]

Taking heart, the exiled barons gathered together some troops, and war began in the neighbourhood of Rome. Cola di Rienzo obtained aid from Louis of Hungary and others, and on 20 November his forces defeated the nobles in the Battle of Porta San Lorenzo, just outside the Porta Tiburtina, a battle in which the tribune himself took no part, but in which his most distinguished foe, Stefano Colonna, was killed.[2]

But this victory did not save him. He passed his time in feasts and pageants, while in a bull the Pope denounced him as a criminal, a pagan and a heretic, until, terrified by a slight disturbance on 15 December, he abdicated his government and fled from Rome. He sought refuge in Naples, but soon he left that city and spent over two years in an Italian mountain monastery.[2]

Life in captivity

editEmerging from his solitude, Cola journeyed to Prague in July 1350, throwing himself upon the protection of Emperor Charles IV. Denouncing the temporal power of the Pope, he implored the Emperor to deliver Italy, and especially Rome, from their oppressors; but, heedless of his invitations, Charles kept him in prison for more than a year in the fortress of Raudnitz, and then handed him over to Pope Clement.[2][3]

At Avignon, where he appeared in August 1352, Cola was tried by three cardinals and was sentenced to death, but this judgment was not carried out, and he remained in prison in spite of appeals from Petrarch for his release.[2]

In December 1352, Clement died, and his successor, Pope Innocent VI, anxious to strike a blow at the baronial rulers of Rome, and seeing in the former tribune an excellent tool for this purpose, pardoned and released Rienzi.[2]

Senator of Rome and death

editThe Pope then sent Cola to Italy with the legate, Cardinal Albornoz, and gave him the title of senator. Having collected a few mercenary troops on the way, Cola entered Rome in August 1354, where he was received with great rejoicing and quickly regained his former position of power.[2]

But this latter term of office was destined to be even shorter than his former one. Having vainly besieged the fortress of Palestrina, he returned to Rome, where he treacherously seized the soldier of fortune Giovanni Moriale, who was put to death, and where, by other cruel and arbitrary deeds, he soon lost the favour of the people. Their passions were quickly aroused and a tumult broke out on 8 October. Cola attempted to address them, but the building in which he stood was set on fire, and while trying to escape in disguise he was murdered by the mob.[2]

Legacy

editDuring the 14th century, Cola di Rienzo was the hero of one of the finest of Petrarch's odes, the Spirito gentil.[2]

Having advocated both the abolition of the Pope's temporal power and the Unification of Italy, Cola re-emerged in the 19th century, transformed into a romantic figure among politically liberal nationalists and adopted as a precursor of the 19th century Risorgimento, which struggled for and eventually achieved both aims. In this process he was reimagined as "the romantic stereotype of the inspired dreamer who foresees the national future" as Adrian Lyttleton expressed it, illustrating his point with Federico Faruffini's Cola di Rienzo Contemplating the Ruins of Rome (1855) of which he remarks, "The language of martyrdom could be freed from its religious context and used against the Church."[5]

Ironically one of Rienzo's descendants, Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci, went on to become Pope Leo XIII.[6]

Cola di Rienzo's life and fate have formed the subject of a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1835), tragic plays by Gustave Drouineau (1826), Mary Russell Mitford (1828),[7] Julius Mosen (1837), and Friedrich Engels (1841),[8] and also of some verses of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1818) by Lord Byron.

Richard Wagner's first successful opera, Rienzi (Dresden, 1842), based on Bulwer-Lytton's novel, took Cola for a central figure, and at the same time, unaware of the Dresden production, Giuseppe Verdi, an ardent and anti-clerical patriot of the Risorgimento, contemplated a Cola di Rienzo.[9]

In 1873 – only three years after the new Kingdom of Italy wrested the city of Rome from papal forces – the rione Prati was laid out, with the new quarter's main street being "Via Cola di Rienzo" and a conspicuous square, Piazza Cola di Rienzo. Pointedly, the name was bestowed precisely on the street connecting the Tiber with the Vatican – at the time, headquarters of a Catholic Church still far from reconciled to the loss of its temporal power. To further drive home the point, the Piazza del Risorgimento was located at the Via Cola di Rienzo's western end, directly touching upon the Church's headquarters.

In 1877 a statue of the tribune by Girolamo Masini, was erected at the foot of Rome's Capitoline Hill. In Rome, in rione Ripa, near the Bocca della Verità there still exists a brick-decorated house of the Middle Ages, distinguished by the appellation of "The House of Pilate", but also traditionally known as Cola di Rienzo's house (in fact it belonged to the patrician Crescenzi family).

Irish poet and playwright John Todhunter wrote a drama in 1881 entitled The True Tragedy Of Rienzi Tribune Of Rome. Shakespearean in style, it is largely historically accurate. Plays about Cola di Rienzo were also written by Polish late 19th century authors Adam Asnyk and Stefan Żeromski, who drew similarities between Rienzo's uprising and the Polish struggle for independence.[10][11]

His letters, edited by A. Gabrielli, were published in vol. vi. of the Fonti per la storia d’Italia (Rome, 1890).[2]

According to August Kubizek, a childhood friend of Adolf Hitler's, it was at a performance of Wagner's opera Rienzi that Hitler, as a teenager, had his first ecstatic vision of the reunification of the German people.[12]

For his demagogic rhetoric, popular appeal and anti-establishment (as nobility) sentiment, some sources consider him an earlier populist[13][14] and a proto-fascist figure.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rendina, Claudio (24 May 2009). la Repubblica (ed.). "Cola di Rienzo ascesa e caduta dell' eroe del popolo" (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Holland, Arthur William (1911). "Rienzi, Cola di". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 323.

- ^ a b c Musto, Ronald G., "Cola Di Rienzo", Oxford Biographies, 21 November 2012, DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0122

- ^ Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1898). History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages. Vol. 6, Part I. Translated by Hamilton, Annie. London: George Bell & Sons. p. 247.

- ^ The cultural context of this reconfiguration of Cola is examined by Adrian Lyttelton, "Creating a National Past: History, Myth and Image in the Risorgimento", in Making and Remaking Italy: the cultivation of national identity around the Risorgimento, 2001:27–76; Cola is examined in pp 61–63 (quote p 63).

- ^ Hayes, Carlton J.H (1941). A Generation of Materialism 1871-1900. p. 142.

- ^ Deathridge, John (1983). "Rienzi... A Few of the Facts". The Musical Times. 124 (1687 (Sep 1983)): 546–549. doi:10.2307/962386. JSTOR 962386.

- ^ König, Johann-Günther (2010). "Friedrich Engels' "Rienzi"". Ossietzky (March 2010). Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- ^ George Martin, Verdi, His Music, Life and Times, 1963:126, mentioning Bulwer-Lytton's "immensely popular historical novel" and remarking "As a leader sprung from the people, Rienzi was at the time a favourite symbol and hero of liberals and republicans throughout Europe."

- ^ Asnyk, Adam (1873). Cola Rienzi: dramat historyczny z XIV wieku w pięciu aktach prozą oryginalnie napisany przez (in Polish). Nowolecki.

- ^ Makowiecki, Andrzej (1978). ""Młodość Stefana Żeromskiego", Jerzy Kądziela, indeks zestawiła Krystyna Podgórecka, Warszawa 1976, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy [recenzja]" (PDF). Pamiętnik Literacki. 2 (69): 263 – via BazHum.

- ^ Kubizek, A. (1955). The Young Hitler I Knew: The Memoirs of Hitler's Childhood Friend ISBN 978-1848326071

- ^ Lee, Alexander (2018). Oxford University Press (ed.). Humanism and Empire: The Imperial Ideal in Fourteenth-Century Italy. Oxford University Press. pp. 206–209. ISBN 9780191662645.

- ^ Wojciehowski, Dolora A. (1995). Stanford University Press (ed.). Old Masters, New Subjects: Early Modern and Poststructuralist Theories of Will. Stanford University Press. p. 60–62. ISBN 9780804723862.

- ^ Musto, Ronald F. (2003). University of California Press (ed.). Apocalypse in Rome: Cola di Rienzo and the Politics of the New Age. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520928725.

Further reading

edit- Ferdinand Gregorovius, Geschichte der Stadt Rom im Mittelalter.

- T. di Carpegna Falconieri, Cola di Rienzo (Roma, Salerno Editrice, 2002).

- Ronald G. Musto, Apocalypse in Rome. Cola di Rienzo and the politics of the New Age (Berkeley & Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2003).

- Christopher Hibbert Rome: the Biography of a City, 1985, 97–105.

- Collins, Amanda L., Greater than emperor: Cola di Rienzo (ca. 1313–54) and the world of fourteenth century Rome (Ann Arbor, MI, 2002) (Stylus. Studies in medieval culture).

- Collins, Amanda L., "The Etruscans in the Renaissance: the sacred destiny of Rome and the Historia Viginti Saeculorum of Giles of Viterbo (c. 1469–1532)," Historical Reflections. Réflexions Historiques, 27 (2001), 107–137.

- Collins, Amanda L., "Cola di Rienzo, the Lateran Basilica, and the Lex de imperio of Vespasian," Mediaeval Studies, 60 (1998), 159–184.

- Beneš, C. Elizabeth, "Mapping a Roman Legend: The House of Cola di Rienzo from Piranesi to Baedeker," Italian Culture, 26 (2008), 53–83.

- Beneš, C. Elizabeth, "Cola di Rienzo and the Lex Regia," Viator 30 (1999), 231–252.

- Francesco Petrarch, The Revolution of Cola di Rienzo, translated from Latin and edited by Mario E. Cosenza; 3rd, revised, edition by Ronald G. Musto (New York; Italica Press, 1996).

- Wright, John (tr. with an intr.), Vita di Cola di Rienzo. The life of Cola di Rienzo (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1975).

- Origo, Iris Tribune of Rome (Hogarth 1938).

External links

edit- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.