Cleator Moor West railway station was opened as "Cleator Moor" by the Cleator and Workington Junction Railway (C&WJR) in 1879. It served the growing industrial town of Cleator Moor, Cumbria, England.[4][5]

Cleator Moor West | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Near site of Cleator Moor West station, 1986 | |||||

| General information | |||||

| Location | Cleator Moor, Copeland England | ||||

| Coordinates | 54°31′30″N 3°31′57″W / 54.5249°N 3.5326°W | ||||

| Grid reference | NY009154 | ||||

| Platforms | 2[1] | ||||

| Other information | |||||

| Status | Disused | ||||

| History | |||||

| Original company | Cleator and Workington Junction Railway | ||||

| Post-grouping | London, Midland and Scottish Railway | ||||

| Key dates | |||||

| 1 October 1879 | Opened as "Cleator Moor" | ||||

| 2 June 1924 | Renamed "Cleator Moor West" | ||||

| 13 April 1931 | Closed[2] | ||||

| 16 September 1963. | Line through the station closed[3] | ||||

| |||||

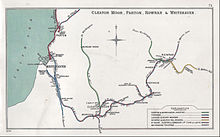

Cleator & Workington Junction Rly | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whitehaven, Cleator & Egremont Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

editThe line was one of the fruits of the rapid industrialisation of West Cumberland in the second half of the nineteenth century, being specifically borne as a reaction to oligopolistic behaviour by the London and North Western and Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railways.[6] The station was on the company's main line from Moor Row to Workington Central. Both line and station opened to passengers on 1 October 1879.

The station was renamed "Cleator Moor West" on 2 June 1924 to avoid confusion with its neighbour on the former Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway line to Rowrah, which was renamed "Cleator Moor East".

All lines in the area were primarily aimed at mineral traffic, notably iron ore, coal and limestone, none more so than the new line to Workington, which earned the local name "The Track of the Ironmasters". General goods and passenger services were provided, but were very small beer compared with mineral traffic.[7]

The founding Act of Parliament of June 1878 confirmed the company's agreement with the Furness Railway that the latter would operate the line for one third of the receipts.[8]

Services

editPassenger trains consisted of antiquated Furness stock hauled largely by elderly Furness engines[9][10] referred to as "...rolling ruins..." by one author after a footplate ride in 1949.[11]

No Sunday passenger service was ever provided on the line.

The initial passenger service in 1879 consisted of

- two Up (northbound) trains a day, leaving Moor Row at 09:20 and 13:45, calling at Cleator Moor, Moresby Parks, Distington, High Harrington and terminating at Workington, taking 30 minutes in all.

- they returned as Down trains, leaving Workington at 10:30 and 16:00

In 1880 the extension northwards to Siddick Junction was opened. The service was extended to run to and from Siddick and an extra train was added, with

- three up trains a day, leaving Moor Row at 07:40, 10:12 and 14:45, taking 30 minutes to Workington and an extra four to proceed to Siddick, where connections were made with the MCR.

- Down trains left Siddick at 08:45, 12:22 and 17:00[12]

By 1922 the service reached its high water mark, with:

- five up trains a day from Moor Row through to Siddick, leaving Moor Row at 07:20, 09:50, 13:15, 16:50 and 1820.

- one train Mondays to Fridays Only from Moor Row to Workington, leaving at 13:45 and also calling at Moresby Junction Halt, making that halt qualify as a publicly advertised passenger station

- one Saturdays Only train leaving Cleator Moor (NB not from Moor Row) at 12:50 for Workington

- one Saturdays Only train leaving Moor Row at 19:35 for Workington

There was one fewer Down train, as the 09:50 Up was provided to give a connection at Siddick with a fast MCR train to Carlisle with connections beyond.[13]

Although not serving Cleator Moor, two Saturdays Only trains left Oatlands at 16:05 and 21:35 for Workington, calling at Distington and High Harrington, with balancing workings leaving Workington at 15:30 and 21:00.

There were also trains using the Lowca Light Railway plying between Lowca and Workington, but they served no "pure" C&WJR stations other than Workington Central.[14]

As with advertised passenger trains, in 1920 workmen's trains ran on the company's three southern routes:

- between Workington Central and Lowca using the Lowca Light Railway

- between Arlecdon (Rowrah's "other station") and Oatlands on the single track "Baird's Line", and

- on the "main line" between Siddick Junction and Moor Row

- from Siddick Junction to Moor Row, calling at all passenger stations except Moresby Parks, calling at Moresby Junction Halt instead

- from Moor Row to Moresby Junction Halt, calling at Cleator Moor and Keekle Colliers' Platform[15]

The situation in 1922 was similar.[13]

The 1920 Working Time Table shows relatively few Goods trains, with just one a day in each direction booked to call at Cleator Moor West.

Mineral traffic was an altogether different matter, dwarfing all other traffic in volume, receipts and profits. The key source summarises it "...the 'Track of the Ironmasters' ran like a main traffic artery through an area honeycombed with mines, quarries and ironworks."[16] The associated drama was all the greater because all the company's lines abounded with steep inclines[17] and sharp curves,[18] frequently requiring banking. The saving grace was that south of Workington at least, most gradients favoured loaded trains. During the First World War especially, the company ran "Double Trains", akin to North American practice, with two mineral trains coupled together and a banking engine behind, i.e. locomotive-wagons-guards van-locomotive-wagons-guards van-banker. Such trains worked regularly between Distington and Cleator Moor,[19] though the practice was discontinued after dark from 1 April 1918.[20]

The workings at Cleator Moor exemplified the line's role. The station was next to a branch to Cleator Moor's dominant ironworks run by the Workington Haematite Iron Company. Iron ore arrived there from the east, via the rival Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway. Coke arrived via the C&WR branch, then Pig iron then went out the same way and headed north along the C&WR, typically bound for Scotland,[21] either via Carlisle or via the Solway Viaduct.

Like any business tied to one or few industries, the railway was at the mercy of trade fluctuations and technological change. The Cumberland iron industry led the charge in the nineteenth century, but became less and less competitive as time passed and local ore became worked out and harder to win, taking the fortunes of the railway with it. The peak year was 1909, when 1,644,514 tons of freight were handled.[22] Ominously for the line, that tonnage was down to just over 800,000 by 1922, bringing receipts of £83,349, compared with passenger fares totalling £6,570.[23]

Rundown and closure

editThe high water mark for tonnage was 1909, the high water mark for progress was 1913, with the opening of the Harrington and Lowca line for passenger traffic. A chronology of the line's affairs from 1876 to 1992 has almost no entries before 1914 which fail to include "opened" or "commenced". After 1918 the position was reversed, when the litany of step-by-step closures and withdrawals was relieved only by a control cabin and a signalbox being erected in 1919 and the Admiralty saving the northern extension in 1937 by establishing an armaments depot at Broughton.[24]

Cleator Moor West closed on 13 April 1931 when normal passenger traffic ended along the line. Diversions and specials, for example to football matches,[25] made use of the line, but it was not easy to use as a through north–south route because all such trains would have to reverse at Moor Row or Corkickle.[26]

An enthusiasts' special ran through on 6 September 1954, the only to do so using main line passenger stock. The next such train to traverse any C&WJR metals did so in 1966 at the north end of the line, three years after the line through Cleator Moor closed.[27]

Afterlife

editBy 1981 the station had been demolished and the cutting had largely been filled in.[28] By 2008 the trackbed had become a public cycleway.[29]

| Preceding station | Disused railways | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keekle Colliers' Platform Line and station closed |

Cleator and Workington Junction Railway | Moor Row Line and station closed |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Butt 1995, p. 63.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Smith & Turner 2012, Map 26.

- ^ Jowett 1989, Map 36.

- ^ Anderson 2002, p. 309.

- ^ Anderson 2002, p. 313.

- ^ Marshall 1981, p. 117.

- ^ Anderson 2002, p. 314.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, pp. 40 & 42.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 51.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 38.

- ^ a b McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Bradshaw 1985, p. 595.

- ^ Haynes 1920, pp. 8–13.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 41.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p.64, Gradient Diagrams.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 25.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, Front cover & pp.42-3.

- ^ Haynes 1920, p. 5.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 40.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Suggitt 2008, p. 65.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, pp. 58–59.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, p. 52.

- ^ Marshall 1981, p. 118.

- ^ McGowan Gradon 2004, pp. 60–1.

- ^ Marshall 1981, p. 165.

- ^ Suggitt 2008, p. 68.

Sources

edit- Anderson, Paul (April 2002). Hawkins, Chris (ed.). "Dog in the Manger? The Track of the Ironmasters". British Railways Illustrated. 11 (7). Clophill: Irwell Press Ltd.

- Bradshaw, George (1985) [July 1922]. Bradshaw's General Railway and Steam Navigation guide for Great Britain and Ireland: A reprint of the July 1922 issue. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8708-5. OCLC 12500436.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Jowett, Alan (March 1989). Jowett's Railway Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland: From Pre-Grouping to the Present Day (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-086-0. OCLC 22311137.

- Haynes, Jas. A. (April 1920). Cleator & Workington Junction Railway Working Time Table. Central Station, Workington: Cleator and Workington Junction Railway.

- McGowan Gradon, W. (2004) [1952]. The Track of the Ironmasters: A History of the Cleator and Workington Junction Railway. Grange-over-Sands: Cumbrian Railways Association. ISBN 0-9540232-2-6.

- Marshall, John (1981). Forgotten Railways: North West England. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8003-6.

- Smith, Paul; Turner, Keith (2012). Railway Atlas Then and Now. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3695-6.

- Suggitt, Gordon (2008). Lost Railways of Cumbria (Railway Series). Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-84674-107-4.

Further reading

edit- British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas And Gazetteer. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing. 1997 [1958]. ISBN 0-7110-0320-3.

- Atterbury, Paul (2009). Along Lost Lines. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2706-7.

- Bairstow, Martin (1995). Railways In The Lake District. Martin Bairstow. ISBN 1-871944-11-2.

- Bowtell, Harold D. (1989). Rails through Lakeland: An Illustrated Journey of the Workington-Cockermouth-Keswick-Penrith Railway 1847-1972. Wyre, Lancashire: Silverling Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-947971-26-2.

- Croughton, Godfrey; Kidner, Roger W.; Young, Alan (1982). Private and Untimetabled Railway Stations, Halts and Stopping Places X 43. Headington, Oxford: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-281-1.

- Joy, David (1983). Lake Counties (Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 094653702X.

- Western, Robert (2001). The Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway OL113. Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-564-0.

External links

edit- Map of the CWJR with photos, via RAILSCOT

- Map of the WC&ER with photos, via RAILSCOT

- The station, via Rail Map Online

- The station on overlain OS maps surveyed from 1898, via National Library of Scotland

- All three closed Cleator Moor stations on a 1948 OS Map, via npe maps

- The station and line, via railwaycodes

- The railways of Cumbria, via Cumbrian Railways Association

- Photos of Cumbrian railways, via Cumbrian Railways Association

- The railways of Cumbria, via Railways_of_Cumbria

- Cumbrian Industrial History, via Cumbria Industrial History Society

- Furness Railtour using many West Cumberland lines 5 September 1954, via sixbellsjunction

- A video tour-de-force of the region's closed lines, via cumbriafilmarchive

- 1882 RCH Diagram showing the station, see page 173 of the pdf, via google

- Haematite, via earthminerals

- Coal and iron ore mining in Cleator Moor, via Haig Pit