The Chickasaw Wars were fought in the first half of the 18th century between the Chickasaw allied with the British against the French and their allies the Choctaws, Quapaw, and Illinois Confederation. The Province of Louisiana extended from Illinois to New Orleans, and the French fought to secure their communications along the Mississippi River. The Chickasaw, dwelling in northern Mississippi and western Tennessee, lay across the French path. Much to the eventual advantage of the British and the later United States, the Chickasaw successfully held their ground. The wars came to an end only with the French cession of New France to the British in 1763 according to terms of the Treaty of Paris.

| Chickasaw Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

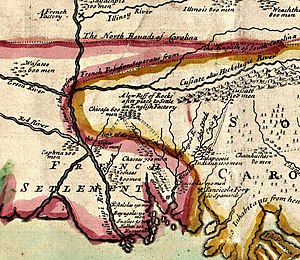

A 1711 map illustrating the position of British-aligned Chickasaw in Mississippi Delta | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Chickasaw |

Choctaw Quapaw Illinois Confederation | ||||||

Choctaw Attacks

editThe governor of Louisiana and founder of New Orleans, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville determined to stop Chickasaw trade with the British. In 1721 he was able to incite the Choctaw who began to raid Chickasaw villages, and to ambush pack trains along the Trader's Path leading to Charleston, South Carolina. In response, the Chickasaw regrouped their villages more tightly for defense, and cemented relations with their British source of guns by establishing a settlement at Savannah Town, South Carolina, in 1723. They blocked French traffic on the Mississippi River by occupying Chickasaw Bluff near present-day Memphis, and bargained for peace with the Choctaw. Bienville himself was recalled to France in 1724 (Gayarre 366–368).

On and off over the following years, the French successfully reignited the Indian conflict. The Choctaw pursued their familiar hit and run tactics: ambushing hunting parties, killing trader's horses, devastating croplands after using superior numbers to drive the Chickasaw into their forts, and killing peace emissaries. Illini and Iroquois occasionally pitched in from the north as well. This war of attrition effectively wore the Chickasaw down, reaching a crisis level in the late 1730s and especially the early 1740s. After a lapse due to strife within the Choctaw, the bloody harassment resumed in the 1750s. The Chickasaw remained obstinate, their situation forcing them to adhere even more closely to the British.

In 1734, Bienville returned to Louisiana, and waged grand campaigns against the Chickasaw in the European style.[1]

Campaign of 1736

editBienville assembled a force in Mobile which he led via Fort Tombecbé up the Tombigbee River (Rive de la Mobile), intending to link with a northern force sweeping down from Fort de Chartres under Pierre D'Artaguiette.

On March 25, 1736, the northern force, a mixture of French with their allies the Illini led by Chief Chicagou, met with disaster while attacking the village of Ogoula Tchetoka near present-day northwest Tupelo, Mississippi. The French were crushed, and d'Artaguiette was killed.

Bienville remained unaware of d'Artaguiette's disaster. On May 26, 1736, he and his army of 1200 French and Choctaw were repulsed in an attack on the fortified Chickasaw village of Ackia (Chickasaw: Aahíkki'ya') in present-day south Tupelo. Bienville returned to Mobile and New Orleans in disgrace.[citation needed]

Campaign of 1739

editBienville was instructed to try again. This time he obtained heavy siege equipment, and assembled his forces at Fort de l'Assumption on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff (present-day Memphis, Tennessee) 120 miles to the west of the Chickasaw villages. Canada contributed troops and Indian allies under Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil and Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville. The force was reduced by disease, and Bienville found himself unable to transport his artillery through the wilderness. After months of delay, Bienville came to terms without armed conflict.

Supposed Campaign of 1752

editThe disgraced Bienville was replaced by Marquis de Vaudreuil in 1742, who continued to encourage Choctaw harassment. He eventually came to the view that another grand effort was needed to end the Chickasaw threat once and for all, and he pleaded his case to his superiors. Many sources describe such an expedition taking place in 1752. None of these sources mention any further details, beyond saying it was an exact repetition of 1736. Dawson A. Phelps determined that the grand effort never took place (Atkinson p. 78), although there was a strong Choctaw attack (one of many over the years) instigated and supported by the French.

Aftermath

editArmed to the teeth in their remote and heavily fortified villages, the Chickasaw maintained themselves albeit with great loss to both population and way of life. The French never defeated the Chickasaw. Enmity between the Illini and the Chickasaw continued long after the war.

References

edit- ^ Taylor, A. (2001). "Chapter 11: French America, 1650—1750". American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-87282-4.

- Atkinson, James R. (2004). Splendid Land, Splendid People. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5033-0. pp. 25–87. Excellent modern history of the Chickasaw prior to their removal

- Gayarre, Charles (1851). Louisiana: Its Colonial History and Romance. Harper and Brothers. OCLC 13850788. Early history with frequent reference to original documents

- Wallace, Joseph (1895). The History of Illinois and Louisiana under the French Rule. R. Clarke. OCLC 17003743. Compilation of secondary sources with emphasis on attempted connection between northern and southern districts of Louisiana

- Hauser, Raymond E.; An Ethnohistory of the Illinois Indian Tribe 1673-1832: doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University, 1973.

- Schlarman, J.; From Quebec to New Orleans. Buechler Publishing, Bellville, IL.