The Chota Nagpur Plateau is a plateau in eastern India, which covers much of Jharkhand state as well as adjacent parts of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal and Bihar. The Indo-Gangetic plain lies to the north and east of the plateau, and the basin of the Mahanadi river lies to the south. The total area of the Chota Nagpur Plateau is approximately 65,000 square kilometres (25,000 sq mi).[1]

| Chota Nagpur Plateau | |

|---|---|

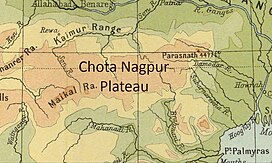

Orographical map of the Chota Nagpur Plateau in the 1909 Imperial Gazetteer of India. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,350 m (4,430 ft) |

| Coordinates | 23°21′N 85°20′E / 23.350°N 85.333°E |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Nagpuri |

| Geography | |

| |

| Location | Jharkhand, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Bihar |

Etymology

editThe name Nagpur is probably taken from Nagavanshis, who ruled in this part of the country. Chhota (small in Hindi) is the misunderstood name of "Chuita" village in the outskirts of Ranchi, which has the remains of an old fort belonging to the Nagavanshis.[2][3]

Geology

editFormation

editThe Chota Nagpur Plateau is a continental plateau—an extensive area of land thrust above the general land.The plateau is composed of Precambrian rocks (i.e., rocks more than about 540 million years old). The plateau has been formed during the Cenozoic by continental uplift due to tectonic forces.[4] The Gondwana substrates attest to the plateau's ancient origin. It is part of the Deccan Plate, which broke free from the southern continent during the Cretaceous to embark on a 50-million-year journey that was interrupted by the collision with the Eurasian continent. The northeastern part of the Deccan Plateau, where this ecoregion sits, was the first area of contact with Eurasia.[5] The history of metamorphism, granitic activities and igneous intrusions in the Chotanagpur area continued for a period from over 1000 Ma to 185 Ma.[6]

Fossil record

editThe Chota Nagpur region has a notable fossil presence. The fossil-rich sedimentary units host fossilized remains across a range of biota, such as angiosperm leaves, fruits, flowers, wood, and fish. This stratigraphy has been associated with the Neogene, specifically the Pliocene epoch, despite a lack of conclusive evidence. Earlier studies identified vertebrate fossils in these sediments, with reported fish fossils with affinities to modern families, linking these deposits to recent ichthyofauna adaptations.[7][8]

Divisions

editThe Chota Nagpur Plateau consists of three steps. The highest step is in the western part of the plateau, where pats as a plateau is locally called, are 910 to 1,070 metres (3,000 to 3,500 ft) above sea level. The highest point is 1,164 metres (3,819 ft). The next part contains larger portions of the old Ranchi and Hazaribagh districts and some parts of old Palamu district, before these were broken up into smaller administrative units. The general height is 610 metres (2,000 ft). The topography in undulating with prominent gneissic hills, often dome-like in outline. The lowest step of the plateau is at an average level of around 300 metres (1,000 ft). It covers the old Manbhum and Singhbhum districts. High hills are a striking part of this section – Parasnath Hills rise to a height of 1,370 metres (4,480 ft) and Dalma Hills to 1,038 metres (3,407 ft).[2] The large plateau is subdivided into several small plateaus or sub-plateaus.

Pat region

editThe western plateau with an average elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above mean sea level merges into the plateau of the Surguja district of Chhattisgarh. The flat topped plateau, locally known as pats are characterized by level surface and accordance of their summit levels shows they are part of one large plateau.[9] Examples include Netarhat Pat, Jamira Pat, Khamar Pat, Rudni Pat and others. The area is also referred to as Western Ranchi Plateau. It is believed to be composed of Deccan basalt lava.[10]

Ranchi Plateau

editThe Ranchi Plateau is the largest part of the Chota Nagpur Plateau. The elevation of the plateau surface in this part is about 700 m (2,300 ft) and gradually slopes down towards south-east into the hilly and undulating region of Singhbhum (earlier the Singhbhum district or what is now the Kolhan division).[11] The plateau is highly dissected. The Damodar River originates here and flows through a rift valley.[4] To the north it is separated from the Hazaribagh plateau by the Damodar trough.[10] To the west is a group of plateaus called pat.[4]

There are many waterfalls at the edges of the Ranchi plateau where rivers coming from over the plateau surface form waterfalls when they descend through the precipitous escarpments of the plateau and enter the area of significantly lower elevation. The North Karo River has formed the 17 m (56 ft) high Pheruaghaugh Falls at the southern margin of the Ranchi plateau. Such falls are called scarp falls. Hundru Falls (75 m) on the Subarnarekha River near Ranchi, Dassam Falls (39.62 m) on the Kanchi River, east of Ranchi, Sadni Falls (60 m) on the Sankh River (Ranchi plateau) are examples of scarp falls. Sometimes waterfalls of various dimensions are formed when tributary streams join the master stream from great heights forming hanging valleys. At Rajrappa (10 m), the Bhera River coming over from the Ranchi Plateau hangs above the Damodar River at its point of confluence with the latter. The Jonha Falls (25.9 m) is another example of this category of falls. The Ganga River hangs over its master stream, the Raru River (to the east of Ranchi city) and forms the said falls.[12]

Hazaribagh Plateau

editThe Hazaribagh plateau is often subdivided into two parts – the higher plateau and the lower plateau. Here the higher plateau is referred to as Hazaribagh plateau and the lower plateau as Koderma plateau. The Hazaribagh plateau on which Hazaribagh town is built is about 64 km (40 mi) east by west and 24 km (15 mi) north by south with an average elevation of 610 m (2,000 ft). The north-eastern and southern faces are mostly abrupt; but to the west it narrows and descends slowly in the neighbourhood of Simaria and Jabra where it curves to the south and connects with the Ranchi Plateau through Tori pargana.[13] It is generally separated from the Ranchi plateau by the Damodar trough.[10]

The western portion of Hazaribagh plateau constitutes a broad watershed between the Damodar drainage on the south and the Lilajan and Mohana rivers on the north. The highest hills in this area are called after the villages of Kasiatu, Hesatu and Hudu, and rise fronting the south 180 m (600 ft) above the general level of the plateau. Further east along the southern face a long spur projects right up to the Damodar river where it ends in Aswa Pahar, elevation 751 metres (2,465 ft). At the south-eastern corner of the plateau is Jilinga Hill at 932 metres (3,057 ft). Mahabar Jarimo at 666 m (2,185 ft) and Barsot at 660 m (2,180 ft) stand in isolation to the east, and on the north-west edge of the plateau Sendraili at 670 m (2,210 ft) and Mahuda at 734 m (2,409 ft) are the most prominent features. Isolated on the plateau, in the neighbourhood of Hazaribagh town are four hills of which the highest Chendwar rises to 860 m (2,810 ft). On all sides it has an exceedingly abrupt scarp, modified only on the south-east. In the south it falls almost sheer in a swoop of 670 m (2,200 ft) to the bed of Bokaro River, below Jilinga Hill. Seen from the north the edge of this plateau has the appearance of a range of hills,[13] at the foot of which (on the Koderma plateau) runs the Grand Trunk Road and NH 2 (new NH19).

Koderma Plateau

editThe Koderma plateau is also referred to as the Hazaribagh lower plateau[13][14] or as the Chauparan-Koderma-Girighi sub-plateau.[15]

The northern face of the Koderma plateau, elevated above the plains of Bihar, has the appearance of a range of hills, but in reality it is the edge of a plateau, 240 metres (800 ft) from the level of the Gaya plain. Eastward this northern edge forms a well-defined watershed between heads of the tributaries of Gaya and those of the Barakar River, which traverses the Koderma and Giridih districts in an easterly direction. The slope of this plateau to the east is uniform and gentle and is continued past the river, which bears to the south-east, into the Santhal Parganas and gradually disappears in the lower plains of Bengal. The western boundary of the plateau is formed by the deep bed of the Lilajan River.The southern boundary consists of the face of the higher plateau, as far as its eastern extremity, where for some distance a low and undistinguished watershed runs eastward to the western spurs of Parasnath Hills. The drainage to the south of this low line passes by the Jamunia River to the Damodar.[13]

Damodar trough

editThe Damodar basin forms a trough between the Ranchi and Hazaribagh plateaus resulting from enormous fractures at their present edges, which caused the land between to sink to a great depth and incidentally preserved from denudation by the Karanpura, Ramgarh and Bokaro coalfields. The northern boundary of the Damodar valley is steep as far as the southeastern corner of the Hazaribagh plateau. On the south of the trough the Damodar keeps close to the edge of the Ranchi plateau till it has passed Ramgarh, after which a turn to the north-east leaves on the right hand a wide and level valley on which the Subarnarekha begins to intrude, south of Gola till the Singhpur Hills divert it to the south. Further to the east the Damodar River passes tamely into the Manbhum sector of lowest step of the Chota Nagpur plateau.[13]

Palamu

editThe Palamu division generally lies at a lower height than the surrounding areas of Chota Nagpur Plateau. On the east the Ranchi plateau intrudes into the division and the southern part of the division merges with the Pat region. On the west are the Surguja highlands of Chhattishgarh and Sonbhadra district of Uttar Pradesh. The Son River touches the north-western corner of the division and then forms the state boundary for about 72 kilometres (45 mi). The general system of the area is a series of parallel ranges of hills running east and west through which the North Koel River passes. The hills in the south are the highest in the area, and the picturesque and isolated cup-like Chhechhari valley is surrounded by lofty hills on every side. Lodh Falls drops from a height of 150 metres (490 ft) from these hills, making it the highest waterfall on the Chota Nagpur Plateau. Netarhat and Pakripat plateaus are physiographically part of the Pat region.[16][17]

Manbhum-Singhbhum

editIn the lowest step of the Chota Nagpur Plateau, the Manbhum area covers the present Purulia district in West Bengal, and Dhanbad district and parts of Bokaro district in Jharkhand, and the Singhbhum area broadly covers Kolhan division of Jharkhand. The Manbhum area has a general elevation of about 300 metres (1,000 ft) and it consists of undulating land with scattered hills – Baghmundi and Ajodhya range, Panchakot and the hills around Jhalda are the prominent ones.[18] Adjacent Bankura district of West Bengal has been described as the "connecting link between the plains of Bengal on the east and Chota Nagpur plateau on the west."[19] The same could be said of the Birbhum district and the Asansol and Durgapur subdivisions of Bardhaman district.

The Singhbhum area contains much more hilly and broken country. The whole of the western part is a mass of hill ranges rising to 910 metres (3,000 ft) in the south-west. Jamshedpur sits on an open plateau, 120 to 240 metres (400 to 800 ft) above mean sea level, with a higher plateau to the south of it. The eastern part is mostly hilly, though near the borders of West Bengal it flattens out into an alluvial plain.[20] In the Singhbhum area, there are hills alternating with valleys, steep mountains, deep forests on the mountain slopes, and, in the river basins, some stretches of comparatively level or undulating country. The centre of the area consists of an upland plateau enclosed by hill ranges. This strip, extending from the Subarnarekha River on the east to the Angarbira range to the west of Chaibasa, is a very fertile area. Saranda forest is reputed to have the best Sal forests in Asia.[21]

Climate

editThe Chota Nagpur Plateau has an attractive climate. For five to six months of the year, from October onward the days are sunny and bracing. The mean temperature in December is 23 °C (73 °F). The nights are cool and temperatures in winter may drop below freezing point in many places. In April and May the day temperature may cross 38 °C (100 °F) but it is very dry and not sultry as in the adjacent plains. The rainy season (June to September) is pleasant.[22] The Chota Nagpur Plateau receives an annual average rainfall of around 1,400 millimetres (55 in), which is less than the rainforested areas of much of India and almost all of it in the monsoon months between June and August.[23]

Ecology

editThe Chota Nagpur dry deciduous forests, a tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests ecoregion, encompasses the plateau. The ecoregion has an area of 122,100 square kilometres (47,100 sq mi), covering most of the state of Jharkhand and adjacent portions of Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

The ecoregion is drier than surrounding ones, including the Eastern Highlands moist deciduous forests that covers the Eastern Ghats and Satpura Range to the south, and the Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests in the lowlands to the east and north.

The plateau is covered with a variety of various habitats of which Sal forest is predominant. The plateau is home to the Palamau Tiger Reserve and other large blocks of natural habitat which are among the few remaining refuges left in India for large populations of tiger and Asian elephants.[5]

Flora

editThe flora of the Chota Nagpur Plateau ranges from dry to wet forests, with trees reaching heights of up to 25 metres (82 ft). Some areas are swampy, while others feature bamboo grasslands and shrubs like Holarrhena and Dodonaea. Key species include sal (Shorea robusta), which provides valuable timber and supports diverse wildlife, and mahua (Madhuca longifolia), known for its fragrant flowers used to make a traditional alcoholic beverage and as a food source for animals. Other significant plants include bamboo (Bambusa), teak (Tectona grandis),and wild mango (Mangifera indica), flame of the forest (Butea monosperma).[24]

Fauna

editThe region is home to diverse wildlife, including apex predators like the tiger (Panthera tigris) and large herbivores such as the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). Ungulates such as the four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis), blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), and chinkara (Gazella bennettii) are also common, alongside predators like the dhole (Cuon alpinus) and the sloth bear (Melursus ursinus). Bird species include the threatened lesser florican (Sypheotides indicus), various hornbills including the Indian grey hornbill (Ocyceros birostris), and a variety of raptors and migratory birds.[25]

Conservation

editThe Chota Nagpur Plateau was once extensively forested, but today over half of its natural forest cover has been removed, largely for grazing land and increasingly intense mining activities. These disruptions pose significant ecological threats. Mining for minerals like coal, iron ore, and bauxite has led to large-scale deforestation, soil erosion, and habitat fragmentation, which critically affects the survival and movement of native wildlife, particularly larger species such as elephants, tigers, and leopards that require extensive, undisturbed areas.

Some conservation efforts are underway, including the establishment of protected areas and wildlife corridors[26]aimed at reconnecting fragmented habitats. However, challenges remain due to limited enforcement of conservation policies and the economic dependence of local communities on mining and agriculture, which places continual pressure on the plateau’s ecological resources.

Protected areas

editAbout 6 percent of the ecoregion's area is within protected areas, comprising 6,720 square kilometres (2,590 sq mi) in 1997. The largest are Palamau Tiger Reserve and Sanjay National Park.[27]

- Bhimbandh Wildlife Sanctuary, Bihar (680 km2)

- Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand (630 km2)

- Gautam Buddha Wildlife Sanctuary, Bihar (110 km2)

- Hazaribag Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand (450 km2)

- Koderma Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand (180 km2)

- Lawalong Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand (410 km2)

- Palamau Tiger Reserve, Jharkhand (1,330 km2)

- Ramnabagan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal (150 km2)

- Sanjay National Park, Madhya Pradesh (1,020 km2, a portion of which is in the Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests ecoregion)

- Semarsot Wildlife Sanctuary, Chhattisgarh (470 km2)

- Simlipal National Park, Odisha (420 km2)

- Saptasajya Wildlife Sanctuary, Odisha (20 km2)

- Tamor Pingla Wildlife Sanctuary, Chhattisgarh (600 km2)

- Topchanchi Wildlife Sanctuary, Jharkhand (40 km2)

Culture

editThe Chota Nagpur region is a culturally rich area with a diverse population comprising various indigenous tribes and ethnic communities. The region is home to tribes like the Santhal, Munda, Oraon, and Ho, alongside non-tribal groups. These groups have distinct traditions, languages, and spiritual practices, often tied closely to nature and ancestral worship. Festivals like Sarhul, Holi and Karam are central to their culture, celebrating harvests and nature with traditional music, dance, and rituals. Craftsmanship is a strong aspect, with communities creating intricate beadwork, pottery, and metalwork.

Human habitation in the region dates back to the Mesolithic-Chalcolithic period, as evidenced by various ancient cave paintings.[28][29][30] Stone tools from the Chota Nagpur Plateau indicate human activity dating back to the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.[28] Additionally, ancient cave paintings at Isko in Hazaribagh district date to the Meso-Chalcolithic period (9000–5000 BCE). The region has seen an dominance of non-tribal populations over time, owing to growth in mining and industrial activities. Large-scale extraction industries in coal and iron mining dominate the economy, alongside growing steel production, power generation, and related infrastructure developments. However, agriculture remains important, with rice, maize, and pulses as staple crops.

Mineral resources

editChota Nagpur plateau is a store house of mineral resources such as mica, bauxite, copper, limestone, iron ore and coal.[4] The Damodar valley is rich in coal, and it is considered as the prime centre of coking coal in the country. Massive coal deposits are found in the central basin spreading over 2,883 square kilometres (1,113 sq mi). The important coalfields in the basin are Jharia, Raniganj, West Bokaro, East Bokaro, Ramgarh, South Karanpura and North Karanpura.[31]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Chhota Nagpur Plateau". mapsofindia. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b Sir John Houlton, Bihar, the Heart of India, pp. 127–128, Orient Longmans, 1949.

- ^ "CHOTA NAGPUR: A NOMENCLATURE IN CONTRADICTION". researchgate.

- ^ a b c d Geography By Yash Pal Singh. FK Publications. ISBN 9788189611859. Retrieved 2 May 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Chhota-Nagpur dry deciduous forests". The Encyclopaedia of Earth. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Ghose, N. C.; Shmakin, B. M.; Smirnov, V. N. (September 1973). "Some geochronological observations on the Precambrians of Chotanagpur, Bihar, India". Geological Magazine. 110 (5): 477–482. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Puri, S. N; Mishra, V. P (1982). "On the find of Upper Tertiary plant, fish and bird fossils near Rajdanda, Palamau district, Bihar". Records of the Geological Survey of India. 112: 55-58. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Hazra, Manoshi; Hazra, Taposhi; Bera, Subir; Khan, Mahasin Ali (2020). "Occurrence of a cyprinid fish (Leuciscinae) from latest Neogene (?Pliocene) sediments of Chotanagpur plateau, eastern India". Current Science. 119 (8): 1367–1370. doi:10.2307/27139024. ISSN 0011-3891. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Sharma, Hari Shanker (1982). Perspectives in geomorphology By Hari Shanker Sharma. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b c "Jharkhand Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Effects of Urbanisation on ground water in Ranchi". Retrieved 2 May 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bharatdwaj, K. (2006). Physical Geography: Hydrosphere By K. Bharadwaj. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788183561679. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Lister, Edward (October 2009). Hazaribagh By Edward Lister. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781115792776. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Natural Resources Data Management System". Ministry of Science and Technology, Govt. of India. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Forest Resources Survey, Hazaribagh 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Sir John Houlton, p. 159

- ^ "Gazetteer of Palamu District". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Sir John Houlton, p. 170

- ^ O’Malley, L.S.S., ICS, Bankura, Bengal District Gazetteers, pp. 1-20, 1995 reprint, Government of West Bengal

- ^ Sir John Houlton, p. 165

- ^ "The West Singhbhum District" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Sir John Houlton, p. 126

- ^ "Damodar Valley". About the Region – Damodar Basin. Ministry of Environments and Forests. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ Agarwal, Vijayluxmi; Paul, S. R. (January 1992). "Floristic elements and distribution pattern in the flora of Chotanagpur (Bihar) India". Feddes Repertorium. 103 (5–6): 381–398. doi:10.1002/fedr.19921030518. ISSN 0014-8962.

- ^ Nath, Bhola (1951). "On a collection of mammals from Chota Nagpur, Bihar". Records of the Zoological Survey of India: 29–44. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Sharma, Lalit Kumar; Mukherjee, Tanoy; Saren, Phakir Chandra; Chandra, Kailash (10 April 2019). "Identifying suitable habitat and corridors for Indian Grey Wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) in Chotta Nagpur Plateau and Lower Gangetic Planes: A species with differential management needs". PLOS ONE. 14 (4): e0215019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215019. ISSN 1932-6203. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Wikramanayake, Eric; Eric Dinerstein; Colby J. Loucks; et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment. Island Press; Washington, DC. pp. 321-322

- ^ a b India – Pre-historic and Proto-historic periods. Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. 2016. p. 14. ISBN 9788123023458.

- ^ "Cave paintings lie in neglect". The Telegraph. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 220. ISBN 9788131711200. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019.

- ^ "Mineral Resources and Coal Mining". Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

Further reading

edit- Gupta, Satya Prakash. Tribes of Chotanagpur Plateau: An Ethno-Nutritional & Pharmacological Cross-Section. Land and people of tribal Bihar series, no. 3. [Patna]: Govt. of Bihar, Welfare Dept, 1974.

- Icke-Schwalbe, Lydia. Die Munda und Oraon in Chota Nagpur - Geschichte, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, Abhandlungen und Berichte des Staatlichen Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden, Band 40; Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1983

- Mukhopadhyay, Subhash Chandra. Geomorphology of the Subarnarekha Basin: The Chota Nagpur Plateau, Eastern India. [Burdwan]: University of Burdwan, 1980.

- Sinha, Birendra K. Light at the End of the Tunnel: A Journey Towards Fulfilment in the Chotanagpur Plateau : a Study in Dynamics of Social-Economic-Cultural-Administrative-Political Growth. [S.l: s.n, 1991.

- Sinha, V. N. P. Chota Nagpur Plateau: A Study in Settlement Geography. New Delhi: K.B. Publications, 1976.

- Chakrabarti D.K. (1994c). Archaeology of the Chhotanagpur plateau and the Bengal basin. In: J.M. Kenoyer (ed.), From Sumer to Meluhha: Contributions to the Archaeology of South and West Asia in Memory of George F. Dales Jr, Wisconsin Archaeological Report, Volume 3, pp. 253–259. Madison: Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin

- Goswami Prodipto (2020). Untold Story of Chota Nagpur: Its Journey with the Colonial Army 1767-1947. Chennai Notion: Press, 2020

External links

edit- Media related to Chota Nagpur Plateau at Wikimedia Commons

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 272.