The cherry-throated tanager (Nemosia rourei) is a critically endangered bird native to the Atlantic Forest in Brazil. Since its description in 1870, based on a shot specimen, there had been no confirmed sightings for more than 100 years, and by the end of the 20th century, it was feared that the species was already extinct. The cherry-throated tanager was rediscovered in 1998 on a private fazenda in the state of Espírito Santo, and soon after on two other sites in the same state, though it disappeared from the fazenda after 2006. By the end of 2023, 20 individuals were known and the total population was estimated to be less than 50 birds. The main threat to its survival is the large-scale destruction of the old-growth rainforest that it requires, and in 2018 it was estimated that the species was restricted to a total area of just 31 km2 (12 sq mi).

| Cherry-throated tanager | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in the Mata de Caetés (Caetés forest) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Genus: | Nemosia |

| Species: | N. rourei

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nemosia rourei Cabanis, 1870

| |

| |

| Distribution within southern Brazil | |

The cherry-throated tanager belongs to the tanager family Thraupidae. It is thought to be most closely related to the only other member of its genus, the hooded tanager, though this has yet to be confirmed by genetic analysis. It has a striking gray, black and white plumage, with a distinctive red throat patch that tapers towards the breast. The yellow or dark amber eyes contrast with a black face mask. Its call is clear and far-carrying. A social species, it lives in flocks that comprise up to eight birds and have large home ranges, in one case about 420 hectares (1,000 acres). Its diet consists of invertebrates such as ants and caterpillars, preferably picked from the horizontal, lichen-covered branches of large trees; the birds have also been observed feeding on fruit. The birds breed once a year, building a cup nest of beard lichen and spider web. Known nests have contained two or three eggs, and other members of the flock may help the breeding pair to feed the chicks.

Taxonomy

editThe cherry-throated tanager was described in 1870 by the German ornithologist Jean Cabanis of the Natural History Museum, Berlin, as Nemosia rourei. Cabanis based the description on a single specimen sent to him by the Swiss ornithologist Carl Euler, who lived on a fazenda in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Euler wrote that he had obtained the specimen from a friend, the ornithologist and veteran bird collector Jean de Roure, and that de Roure received the specimen after it was shot in "Muriahié" (Muriaé), Minas Gerais, at the northern bank of the Paraíba do Sul river.[2][3]: 574 [4] A life illustration of the new species was published two years after the description, in 1872. The specimen, which became the holotype of the species, is an adult male and still part of the collection in Berlin.[4] The bird essentially remained known only from this single specimen for more than 100 years, before the species was rediscovered in 1998.[5] There is, however, evidence that two additional specimens existed: In 1926, the ornithologist Emilie Snethlage, while reporting on her failed attempts to find an individual of the species in the wild, mentioned a mounted pair in the collection of the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. These specimens are also included in an 1876 collection catalog but are missing in a 1940 inventory, and therefore must have disappeared by that time.[4]

Cabanis named the new species Nemosia rourei, with the specific name honouring de Roure, as was requested by Euler.[3]: 36 The name Nemosia derives from the Greek nemos meaning 'glade' or 'dell'.[6] "Cherry-throated tanager" is the official English common name designated by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOU).[7] The Portuguese name of the bird is saíra-apunhalada, which means 'stabbed tanager' and refers to the blood-red throat patch.[5]

Classification

editThe tanagers (Thraupidae) are the second-largest family of birds, with 384 species as of 2020, and are restricted to the Americas.[8][9] In his 1870 description, Cabanis noted that the cherry-throated tanager is not obviously related to any other tanager species, but decided to place it in the genus Nemosia, which contains only one other species, the hooded tanager (Nemosia pileata).[2] This classification still stands; although the cherry-throated tanager was never included in a genetic analysis, a 2016 study considered its placement within Nemosia to be preliminary but reasonable because of similarities in iris color and plumage with the hooded tanager.[8][5] A 2024 review, however, cautioned that the nest, behavior, and vocalizations of the two Nemosia species differ considerably from each other.[5] The 2016 analysis found Nemosia to be part of the subfamily Nemosiinae, which consists of only five species – the two Nemosia species, the blue-backed tanager (Cyanicterus cyanicterus), the white-capped tanager (Sericossypha albocristata), and the scarlet-throated tanager (Compsothraupis loricata). The relationships of Nemosia with the other genera of the Nemosiinae remain unclear.[8]

Description

editThe cherry-throated tanager is a visually distinctive bird with an overall gray, black, and white plumage and a conspicuous bright red patch on the chest and throat.[5] The red patch varies in shape and extent, and a pointed extension typically reaches down to the upper breast.[4][5] The patch may also contain some white feathers.[5] The red patch contrasts with a broad black face mask that extends from the forehead across the eyes. This mask almost meets at the nape (back of the head), enclosing the crown (top of the head) almost entirely. The crown is gray and separated from the black band by a white line. The undersides are white, contrasting strongly with the red patch.[5][2]

The upper sides are gray, and the rump and the uppertail coverts (feathers at the base of the tail) are a lighter gray.[5] The uppertail coverts have white spots at their ends, which may serve a signaling function as the birds sometimes prominently display them.[4] The rectrices (primary feathers of the tail) are black with a square-shaped end. The undertail coverts are white and reach down a bit more than half the length of the tail.[5][4] The wings are mostly black, but the tertials (inner flight feathers) have a gray-white area that is broadest towards their tips, creating a striped wing patch.[4][5][2] The inner edge of the outer flight feathers (primaries) is partly white, but this can only be observed when the wing is extended.[5] The upperwing coverts are black with a blueish shine, and the gray scapulars (shoulder feathers) sometimes overlap the wing to form a gray shoulder patch. The legs and feet are pink; the claws are marginally darker. The iris is yellow to dark amber, and the beak is black.[5]

Males and females are similar in appearance. Juveniles resemble adults but have the throat patch dull brown rather than red, and a darker iris.[4][5] In chicks and fledgings, the gape flange (base of the beak) is pale whitish or yellowish.[5] Measurements have been obtained from only two individuals, the holotype specimen and a live bird that was banded in 1998.[5] The holotype specimen is 14 cm (5.5 in) in length, with a wing length of 83 cm (33 in), a tail length of 6 cm (2.4 in), a tarsus (the lowest, featherless part of the leg) length of 20.3 mm (0.80 in), and a bill length of 1.7 cm (0.67 in). The live bird was 12.5 cm (4.9 in) in length, and its bill was 0.9 cm (0.35 in) in length. Its body weight was 22 g (0.78 oz).[5][4]

The cherry-throated tanager is unlikely to be confused with any other species when observation conditions are good. The red-cowled cardinal has a superficially similar color pattern when seen from a distance but differs in habitat and does not co-occur with the cherry-throated tanager. The only other Nemosia species, the hooded tanager, has no red and also has never been confirmed to co-occur with the cherry-throated. The rufous-headed tanager shares the same habitat but lacks the black head band and has a chestnut rather than bright red throat.[5]

Vocalizations

editThe cherry-throated tanager has a clear, far-carrying call that has been described as "péuuu" or "peéyr". This note is given singly during foraging, or in a row of two or three in rapid succession. In the latter case, it is typically followed by two shorter and high-pitched notes that have been described as "see'ee" or "pit-pit", and additional "péuuu" calls may be added to the middle or end of the sequence. A call sequence lasts between 0.3 and 1 seconds.[4][5][10] Another vocalization consists of the same notes but is less regular and interspersed with rapid chittering; it is given especially when the birds reply to tape recordings and therefore might represent the song.[4][5] Another call is a high but weaker "ti".[5]

Habitat and distribution

editThe cherry-throated tanager is a local endemic of the Atlantic Forest, the second largest rainforest of the Americas, and one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Originally, this forest covered 1.6 million hectares (4 million acres), mostly in Brazil but extending south into parts of Paraguay and Argentina.[5][11] The cherry-throated tanager has been recorded from mountainous regions at elevations between 850 and 1250 m, where it prefers tall trees with abundant epiphytes.[12] The species requires structured, old-growth forest.[13]: 7 Given the paucity of historical records, it was probably a rare species even before the onset of widespread habitat destruction.[5][12] Its home ranges are probably large and, in the Mata de Caetés (Caetés forest), have been estimated at 420 ha (1,000 acres).[13]: 7 The birds have sometimes been observed in plantations of coffee, eucalyptus, and Pinus, which the birds probably only use as corridors to move between patches of prime habitat. There is no indication of altitudinal or other migrations.[5]

The cherry-throated tanager currently occurs at only two localities – the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve and the Mata de Caetés – and had been recorded from at least two others (Itarana and Conceição do Castelo) from which it has disappeared. All these localities are in the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo. There has been some debate about the provenance of the holotype specimen, which Euler claimed was from Muriaé in Minas Gerais. In 1999, the Brazilian ornithologist José Fernando Pacheco argued that the holotype might instead be from Macaé de Cima ("Macahé" in the late 19th century) near Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro state, where de Roure collected many of his other bird specimens. According to this hypothesis, "Muriahié" might have been a transcription error introduced when the locality information was passed on in hand-written letters. Pacheco further argued that neither altitude nor habitat at Muriaé seem to agree with what is now known about the ecology of the species.[4][14] However, a 2024 review considers it likely that the specimen is from the montane area north of Muriaé; this area is part of the same mountain complex as the other known localities, whereas Nova Friburgo is of a different mountain range.[5]

Behavior and ecology

editA social species, the cherry-throated tanager is often seen in flocks of two to eight individuals, although single birds are sometimes seen. It has often been observed that one of the flock members sat higher and was noisier than the others, for unclear reasons. The flock members have also been observed feeding each other, but these might have been adults feeding grown juveniles. If undisturbed, the birds may use regular "tracks" to visit feeding sites over the course of the day; these tracks vary according to season.[5][12][13]: 9 The home range of the flock in the Mata de Caetés has been estimated at 420 ha (1,000 acres); this flock travelled approximately 2.2 km (1.4 mi) per day, including flights of up to 50 m (160 ft).[13]: 7, 58 The species, like many tanagers, joins mixed-species feeding flocks. Those in which N. rourei was observed to participate were usually led by sibilant sirystes and contained chestnut-crowned becards and rufous-headed tanagers as "core" species. One study reported that cherry-throated tanagers have been part of a mixed-species flock in 35% of all sightings. Other observations of interactions with other bird species include an individual that had caught a large butterfly and was chased by a golden-chevroned tanager, and another individual that was apparently being attacked by a black-necked aracari.[12][5][13]: 9 In 2023, black-necked aracaris preyed upon a nest at the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve.[15]

The species primarily feeds on invertebrates including caterpillars, butterflies, and ants.[5] Feeding takes place in the forest canopy on tall trees, preferably on large and horizontal branches with abundant lichen. Here, the birds search for prey with quick hops, extending their necks to pick up food items from the side and undersides of branches, from leaves, and beneath lichen.[4][5] At times, the species makes short flights to capture insects such as termites from the air.[13]: 8 The birds do not hang down from branches.[4][5] Eucalyptus flowers are visited, though it is not clear whether to feed on nectar or on insects.[12] Bauer and colleagues, in 2000, observed that fruits are not consumed even when available in various sizes, but in 2021, a flock was observed feeding on fruit, which the birds also passed on to their chicks.[13]: 46 The parasites of the species are unknown, except for a female ixodid tick that one bird was observed to remove from its throat. Longevity data is only available for the single banded bird, which lived for at least 6 years.[5][12]

Reproduction

editA possible courtship behavior was observed in October, where the presumed male, being watched by the presumed female, was sitting high, tentatively flapping its half-open wings and calling faintly.[12] On November 25, 1998, the first nest was observed, being located in a shallow depression at the base of a horizontal branch, at mid-height of the tree. A group of three birds were found around the nest and called frequently, with one of the birds responding unusually aggressively to playback of recorded calls, immediately flying down towards the sound device. Two of the birds were constructing the nest, repeatedly bringing nest material, mostly lichen, and incorporating it into the nest by sitting on it and shaping it with movements of their bodies and their bills. The third bird observed was nearby but less active and did not participate in nest building.[16]

Three additional nests have been found by 2020, with nesting taking place from October to December. The nests were mostly composed of beard lichen (Usnea) and refined with spider webs. In one case, three birds of the flock assisted in feeding the chicks, and in another, five birds assisted. In yet another case, however, only two birds (probably the breeding pair) cared for the chicks. One nest contained three eggs, of which two hatched. Two more nests were found in 2021, one of which produced three chicks. It is likely that the species nests only once a year and chooses a different nesting site each year. Only one breeding pair per flock has been observed, although it cannot be excluded that the flocks have multiple pairs. It is likely that only one individual incubates the eggs, as it has never been observed that one bird relieved the other, although it is unknown whether it is the male or the female that incubates.[13]: 8–9, 46

Status

editHistorical sightings

editIn 1941, the German-Brazilian ornithologist Helmut Sick observed a group of eight tanagers at Jatibocas in Itarana, Espírito Santo. He was not able to identify the species, but recorded the appearance of the birds in his field book. It was not until he examined the holotype specimen in Berlin in 1976 that he realized he had seen a flock of cherry-throated tanagers.[4][17]: 119

In 1994, the bird artist Eduardo P. Brettas observed a bird with a red throat patch at a fazenda near Pirapetinga, Minas Gerais. The bird was part of a mixed species feeding flock that also included the hooded tanager. Brettas declared that he first thought that he saw a cardinal-tanager (Paroaria), but identified the bird as a cherry-throated tanager after comparing his field sketch with an illustration published in Sick's 1993 book Birds in Brazil: a natural history during a library visit. In the following two years, three groups of ornithologists visited the fazenda for multiple days in an attempt to confirm Brettas observation, but did not encounter the species. In 2000, Claudia Bauer and colleagues pointed out that the extent of the black face mask as seen in the 1993 book illustration is incorrect, and that Brettas's sketch showed the same mistake, adding to the doubts about the observation's validity.[4]

Another possible sighting was made in October 1995 in the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve in Espírito Santo. The British ornithologist Derek A. Scott, while leading a group of birdwatchers, briefly saw a bird with a striking red throat patch in the canopy overhead while observing a mixed-species feeding flock; the bird immediately took off and flew about 50 m (160 ft) to perch on a tree at the roadside, and then flew out of sight shortly after. No other members of the birding group except for the tour director saw the bird, and an observation with the telescope was not possible. In a 1997 publication discussing his observation, Scott noted that the bird he saw clearly matched the cherry-throated tanager, but that the red throat patch was not pointed and extending over the breast as in the holotype specimen, but square-shaped. This mismatch could be explained by variation between individuals, or – if the bird had been a female – by possible differences between the sexes. As an alternative hypothesis, Scott suggested that the bird could have been a hybrid between the hooded tanager and the rufous-headed tanager, in which case the holotype specimen could also represent a hybrid rather than a distinct species. According to Scott, this hypothesis may explain how a highly distinctive bird could exist in a nature reserve that is relatively well known and has been frequented by birdwatchers since the 1970s.[18] The idea that the holotype specimen might be a hybrid had already been mentioned by the American ornithologist Charles Sibley in 1996, although without further elaboration.[4]

In the final two decades of the 20th century, several authors feared that the species could already be extinct or close to extinction, given the lack of confirmed observations and the extensive deforestation in south-eastern Brazil.[4] For example, Scott and Brooke remarked in 1985 that "there seems little hope that this distinctive, presumably forest, species could still be extant".[4] Some ornithologists even thought that the holotype specimen was an artifact composed of skins of other species.[4]

Rediscovery

editThe species was rediscovered by a group of six ornithologists on February 22, 1998, in a forest fragment that is part of the Fazenda Pindobas IV, in Conceição do Castelo. The group was undertaking the last of seven visits to different forest fragments in southern Espírito Santo, a poorly known part of the Atlantic Forest, to better understand the distribution of resident bird species. The first bird was spotted by the master's student Claudia Bauer, who immediately identified it as a cherry-throated tanager. The group then observed at least two more individuals, all part of the same mixed-species foraging flock, for about 20 minutes. Two days later, the researchers returned to the site to document their observation; they encountered the same flock, this time containing four cherry-throated tanagers and 18 other bird species. The tanagers were observed for approximately 1.5 hours and attracted with tape recordings of their calls to get better views of their plumage; photographs were also taken.[4][19]

The rediscovery of the species prompted a number of surveys in search for additional populations, and the newly gained knowledge about the bird's distinctive calls facilitated observations. In 2002, the British ornithologist Guy M. Kirwan heard the calls in the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve, where Scott had made his possible observation in 1995. The birds were part of a very large mixed-species flock of possibly more than 100 birds, and Kirwan was unable to see one of the cherry-throated tanagers. Early in the next year, Kirwan again heard the calls and spotted one or two individuals. In 2003, the presence of the species was also confirmed in the Mata de Caetés in Vargem Alta, Espírito Santo by a birdwatching party. The Brazilian ornithologist Pedro Rogerio de Paz, who led the group, heard calls of several birds which he then attracted by playing recorded calls. A total of eight individuals showed up, the largest group of cherry-throated tanagers observed since 1941, when Sick also observed a group of eight. The species was repeatedly observed at Caetés in the following months. All confirmed sightings of the cherry-throated tanager have been in the state of Espírito Santo, and the species was not found in suitable habitat outside this state despite several searches.[12] Modeling of the potential distribution of the species suggested that Caparaó National Park might be suitable for the species, but 2021 surveys in the area failed to detect it.[13]: 6

As of 2024, the cherry-throated tanager is thought to survive at only two localities – the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve and the Mata de Caetés – and has probably disappeared from at least two areas where it was previously recorded.[5] Around Itarana, where Sick observed a flock in 1941, there were three possible sightings in the late 1990s, but the area has since been mostly deforested and no further observations have been made.[5] At the Fazenda Pindobas IV in Conceição do Castelo, where Bauer rediscovered the species in 1998, the birds were regularly observed in subsequent years in two connected forest fragments. In 2000, forest was cleared on a property bordering these forests to make room for coffee plantations. In 2002, a company explored another property bordering one of the forest fragments for marble and granite using explosives; the detonations led to a decrease in activity of the cherry-throated tanagers and of other bird species. The explorations were halted by the authorities. The tanagers temporarily disappeared from one of the two forest fragments after more than 90 vehicles participating in the Enduro da Polenta, a local off-road race, crossed the forest patch illegally and without the approval of the landowners. Such races are popular in Espírito Santo and have affected nature reserves elsewhere in the state.[12] Since 2006, no further sightings of the cherry-throated tanager were reported from the fazenda, despite targeted surveys.[5]

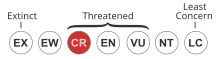

Population status and threats

editThe cherry-throated tanager has been classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) since 1994.[1] It is also listed as Critically Endangered in the Regional Red Lists of Brazil, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais,[20] and the population is thought to be in decline.[1][13]: 6 In 2000, the IUCN estimated the total population at 50 to 249 individuals, though a 2005 study deemed this relatively optimistic estimate to be premature. The known population in 2005 consisted of 14 individuals.[1][12] In 2008, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) estimated the total population at no more than 20 individuals.[20] In 2018, the IUCN gave an estimate of 30 to 200 individuals, while the ICMBio stated that the total population does not exceed 50 adult birds.[1][20] The number of known individuals increased from 10 in 2020 to 20 by the end of 2023, probably thanks to increased conservation efforts at Mata de Caetés. In 2023, the Mata da Caetés probably had 15 individuals, while the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve had five individuals.[12][5][5] A 2024 review concludes that the total population is probably much smaller than 50 birds as little suitable habitat remains, although it is possible that the relatively large Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve houses yet undetected birds.[5] The area occupied by the species has been estimated at just 31 km2 (12 sq mi) by the IUCN in 2018,[1] and the two known localities are separated by approximately 84 km (52 mi) of mostly deforested landscape.[13]: 6

The major threat to its survival is forest degradation, fragmentation, and deforestation. Remaining forest fragments are often insufficiently protected and become the target of real estate speculation, are cleared to gain space for crops such as coffee and Eucalyptus, and are affected by the construction of new infrastructure and urbanization. Forests become degraded by cutting trees for timber, often at small scales but also at larger scales, for example to produce charcoal. The extraction of heart of palm (Euterpe edulis) leads to additional forest degradation. The cherry-throated tanager is particularly susceptible to forest fragmentation and degradation as it requires old-growth forests and avoids areas close to forest edges. The very small population size makes the species highly susceptible to unforeseen events such as natural disasters or variations in natural processes such as predation, and may potentially lead to inbreeding.[5][13]: 21–23

Additional threats include the mining of granite, marble, and limestone that produces dust and leads to heavy traffic and noise pollution due to frequent blasting. The excessive use of pesticides in the region is a potential threat as it may reduce prey abundance. Poaching is feared to become a concern once the species becomes more widely known. Tourism targeting the species can be problematic if sound recordings are used excessively to attract the birds. The effects of climate change on the region remain poorly understood but will probably include higher temperatures, less rain, and more frequent storms.[13]: 21–23 [5] Another risk is the lack of support for conservation actions and negative attitudes towards the remaining forests in the local populace. A 2020 survey conducted in the Mata de Caetés area showed that most locals did not know about the species, with some believing that the species was introduced to the area to enforce conservation of forests.[13]: 11, 22

Conservation

editThe cherry-throated tanager occurs in the Augusto Ruschi Biological Reserve, a protected area of 35.6 km2 (13.7 sq mi), as well as in the Mata de Caetés, a forested area of over 30 km2 (12 sq mi) that, when the species was discovered there in 2003, was unprotected and split in several properties.[12][5] From 2011, the nonprofit organization SAVE Brasil pushed for a large public nature reserve in the Mata de Caetés. The state government approved the project in 2015 but later abandoned it due to local opposition.[13]: 9 [21] Instead of a public reserve, a smaller private nature reserve, the Águia Branca Private Reserve, was established in 2017 to protect 16.88 km2 (6.52 sq mi) of the Mata de Caetés, including parts of the area in which the tanagers occur.[22] In 2021, the Marcos Daniel Institute, supported by several nonprofits, acquired another 6.67 km2 (2.58 sq mi) to create a second private reserve, the Reserva Kaetés.[23] The entire Mata de Caetés was included in the Pedra Azul–Forno Grande ecological corridor, a priority area for conservation recognized by the state.[5]

Since 2020, the Cherry-throated Tanager Conservation Program of the Marcos Daniel Institute has implemented various conservation measures such as monitoring, research, and public engagement.[5] In 2020, the team erected an observation platform about 30 m (98 ft) away from a nest in the Mata de Caetés and used a drone to monitor eggs and chicks. To increase breeding success, potential predators such as black capuchins and channel-billed toucans were chased away, and supplemental feeding of mealworms has been tried.[13]: 9–10 Several other nests have been successfully protected since, and the team published an action plan for the conservation of the species in 2021.[5][13] There are proposals to develop ecotourism around the tanager, which could potentially benefit local communities.[13]: 40 It furthermore serves as a flagship species to educate and involve local communities, contributing to the protection of the remaining forests.[13]: 44 [21][24] Such public engagement may directly benefit lesser-known Atlantic Forest endemics; for example, farmers have discovered additional localities of the critically endangered catfish Trichogenes claviger after learning about this species during campaigns focused on the cherry-throated tanager.[24]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2018). "Nemosia rourei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22722293A130617765. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22722293A130617765.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Cabanis, Jean (1870). "Ueber eine neue brasilische Nemosie oder Wald-Tangare, Nemosia Rourei nov. spec" [About a new Brazilian Nemosia or Forest Tanager, Nemosia Rourei nov. spec.]. Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 18 (6): 459–460. Bibcode:1870JOrni..18..459.. doi:10.1007/BF02259505.

- ^ a b Sick, Helmut (1993). Birds in Brazil: a natural history. Better World Books. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08569-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bauer, Claudia; Pacheco, José Fernando; Venturini, Ana Cristina; Whitney, Bret M. (June 2000). "Rediscovery of the Cherry-throated Tanager Nemosia rourei in southern Espírito Santo, Brazil" (PDF). Bird Conservation International. 10 (2): 97–108. doi:10.1017/S0959270900000095.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Phalan, B. T.; Magnago, G. R.; Hilty, S. (2024). Kirwan, G. M.; Keeney, B. K.; Sly, N. D. (eds.). "Cherry-throated Tanager (Nemosia rourei), version 2.0". Birds of the World Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. doi:10.2173/bow.chttan1.02.

- ^ Jobling, J.A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. OCLC 1040808348.

- ^ Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P. (July 2021). "IOC World Bird List (v 14.1)". Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Burns, Kevin J.; Shultz, Allison J.; Title, Pascal O.; Mason, Nicholas A.; Barker, F. Keith; Klicka, John; Lanyon, Scott M.; Lovette, Irby J. (2014). "Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 75: 41–77. Bibcode:2014MolPE..75...41B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.006. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 24583021.

- ^ Winkler, D. W.; Billerman, S. M.; Lovette, I. J. (2020). Billerman, S. M.; Keeney, B. K.; Rodewald, P. G.; Schulenberg, T. S. (eds.). "Tanagers and Allies (Thraupidae), version 1.0". Birds of the World Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. doi:10.2173/bow.thraup2.01.

- ^ Ridgely, R.S.; Gwynne, J.A.; Guy, T.; Argel, M. (2016). Wildlife Conservation Society Birds of Brazil: The Atlantic Forest of Southeast Brazil, Including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro: Volume 2. Ithaca: Comstock Publishing. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-5017-0453-6.

- ^ Marques, Marcia C. M.; Trindade, Weverton; Bohn, Amabily; Grelle, Carlos E. V. (2021). "The Atlantic Forest: An Introduction to the Megadiverse Forest of South America". In Marcia C. M. Marques, Carlos E. V. Grelle (ed.). The Atlantic Forest: History, Biodiversity, Threats and Opportunities of the Mega-diverse Forest. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-030-55322-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Venturini, Ana Cristina; de Paz, Pedro Rogerio; Kirwan, Guy M. (2005). "A new locality and records of Cherry-throated Tanager Nemosia rourei in Espírito Santo, south-east Brazil, with fresh natural history data for the species" (PDF). Cotinga. 24: 60–70.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Santos, Marcelo Renan de Deus; Barbosa, Antonio Eduardo Araujo; Caetano, Valdivia Rocha Ferreira; Cordero-Schmidt, Eugenia; Fernandes, Katlin Camila; Magnago, Gustavo; Phalan, Benjamin Timothy; Rocha, Fabiana Lopes; Somenzari, Marina; Alves, Maria Alice; Amaral, Fabio; Bichinski, Tony; Bosso, Paloma; Chaves, Flávia; Cometti, Sayonara; Develey, Pedro; Hennessey, Bennett; Bruslund, Simon; Hoffmann, Diego; Jones, Carl; Lobato, Aline; Massaioli, Marcos; Mathias, Leonardo Brioschi; Nunes, Savana de Freitas; Owen, Andrew; Passamani, Jacques; Reillo, Paul; Reisfeld, Alice; Ribon, Rômulo; Rosa, Gustavo; Sampaio, Claudia; Silveira, Luis Fábio; Son, Luiz; Whitney, Bret; Phalan, Benjamin T. (2021). Workshop for the Preparation of the Action Plan and Integrated Management Strategies for the Conservation of the Cherry Throated Tanager (Nemosia rourei): Final report (PDF). Vitória, ES: Instituto Marcos Daniel. ISBN 978-65-89669-07-4.

- ^ Pacheco, José Fernando (1999). "É de Minas Gerais o exemplar único e original de Nemosia rourei?" [Is the unique and original specimen of Nemosia rourei from Minas Gerais?] (PDF). Atualidades Ornitológicas (in Portuguese). 89 (7).

- ^ Instituto Marcos Daniel (2023). "Prêmio biguá 2023!" (PDF). Saíra News (in Portuguese). 002.

- ^ Venturini, Ana Cristina; de Paz, Pedro Rogerio; Kirwan, Guy M. (2002). "First breeding data for Cherry-throated Tanager Nemosia rourei" (PDF). Cotinga. 17: 42–45.

- ^ Sick, Helmut (1979). "Notes on some Brazilian birds". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 99 (4): 115–120.

- ^ Scott, Derek A. (1997). "A possible re-sighting of the Cherry-throated Tanager Nemosia rourei in Espírito Santo, Brazil" (PDF). Cotinga. 7: 61–63.

- ^ Bauer, Claudia; Pacheco, José Fernando; Venturini, Ana Cristina; de Paz, Pedro Rogerio; Rehen, Mariana Pacheco; do Carmo, Luciano Petronetto (1998). "O primeiro registro documentado do séc. XX da saíra-apunhalada, Nemosia rourei Cabanis, 1870, uma espécie enigmática do sudeste do Brasil" [The first documented record from the 20th century of the cherry-throated tanager, Nemosia rourei Cabanis, 1870, an enigmatic species from southeastern Brazil]. Atualidades Ornitológicas (in Portuguese). 82 (6). Archived from the original on 2015-12-10.

- ^ a b c ICMBio (2018). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume III – Aves [Red Book of Endangered Brazilian Fauna: Volume III – Birds] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brasília, DF, Brazil: Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade and Ministério do Meio Ambiente.

- ^ a b "Cherry-throated tanager conservation case study". The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Fauna & Flora International (2017). "Briefly". Oryx. 51 (4): 571–580. doi:10.1017/S0030605317001302. ISSN 0030-6053.

- ^ Instituto Marcos Daniel (2024). "Reserva Kaetés" (PDF). Saíra News (in Portuguese). 003.

- ^ a b Silva, Juliana Paulo; Sarmento-Soares, Luisa Maria; Tonini, Lorena; Freitas, Joelcio (2023). "The contribution of local people to species conservation: the case of the catfish Trichogenes claviger in south-east Brazil". Oryx. 57 (6): 693. doi:10.1017/S0030605323000893. ISSN 0030-6053.