Crawford Goldsby (February 8, 1876 – March 17, 1896), also known by the alias Cherokee Bill, was an American outlaw. Responsible for the murders of eight men (including his brother-in-law), he and his gang terrorized the Indian Territory for over two years.

Crawford Goldsby | |

|---|---|

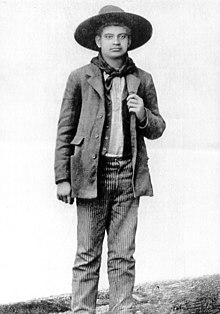

Goldsby c. 1896 | |

| Born | February 8, 1876 San Angelo, Texas, United States |

| Died | March 17, 1896 (aged 20) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | Cherokee Bill |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death by hanging |

Family

editCrawford's father, George Goldsby, was from Perry County, Alabama, a sergeant of the Tenth United States Cavalry, and a Buffalo Soldier. His mother Ellen Beck Goldsby Lynch was a Cherokee freedwoman of mixed African, Native, and white ancestry. She was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation born in the Delaware District, is listed on the Dawes Rolls, and had Cherokee heritage through her father's side.[1][2][3] His mother and her parents, Tempe and Luge Beck, were once enslaved people owned by Cherokee Nation citizen Jeffery Beck; they continued to reside in Indian Territory after becoming free. Crawford Goldsby had one sister, Georgia, and two brothers, Luther and Clarence. His siblings are listed on the Dawes Rolls.[4] In a signed deposition on January 29, 1912, George Goldsby stated that he was born in Perry County, Alabama, on February 22, 1843. His father was Thornton Goldsby of Selma, Alabama, and his mother Hester King, who resided on her own place west of Summerfield Road between Selma and Marion, Alabama. George also stated that he had four brothers and two sisters by the same father and mother: Crawford, Abner, Joseph, Blevens, Mary, and Susie.[5]

George served as a hired servant with a Confederate infantry regiment during the American Civil War. While serving during the Battle of Gettysburg, he fled and went to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he worked as a teamster in a Union Army quartermaster unit and subsequently enlisted as a white man in the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment under the name of George Goosby. (The spelling sometimes varied between Goosbey and Goosley).[5] After the Civil War ended, he returned to the Selma area. During his last visit, rumor spread that he would be captured and lynched for fighting with the Union Army, after which he departed the area for the Indian Territory.[5] In 1867, Goldsby enlisted in the 10th Cavalry Regiment (Buffalo Soldier) under his proper name, and by 1872 was promoted to sergeant major. After the expiration of his five-year term, he re-enlisted and became first sergeant of Company D, 10th Cavalry.[5]

Early life

editGoldsby was born to Sgt. George and Ellen (née Beck) Goldsby on February 8, 1876, at Fort Concho in San Angelo, Texas. During 1878 (when Crawford Goldsby was two years old), serious trouble began to occur in San Angela (San Angelo), Texas, between the black soldiers and cowboys and hunters. The incident that led to the largest confrontation took place in Morris' saloon. A group of cowboys and hunters ripped the chevrons from the sleeves of a Company D sergeant and the stripes from his pants. The soldier returned to the post and enlisted the aid of fellow soldiers, who armed themselves with carbines and returned to the saloon. A blazing gunfight commenced, resulting in one hunter being killed and two others wounded. One private was killed and another wounded.[5]

Texas Ranger Captain G. W. Arrington, along with a party of rangers, went on-post (at Fort Concho) in an attempt to arrest George Goldsby, charging that he was responsible for arming the soldiers. Colonel Benjamin Grierson, post commander, challenged the authority of the rangers in a federal fort.[5] Goldsby apparently knew that the Army could not, or would not, protect him away from the post, so he went AWOL. He escaped from Texas into the Indian Territory.[5] Sometime after being abandoned at Fort Concho, Ellen Beck Goldsby moved with her family to Fort Gibson, Indian Territory. She left her son, Crawford Goldsby, in the care of an elderly black lady known as "Aunty" Amanda Foster. Foster cared for him until he was seven years old, then Crawford was sent to the Indian school at Cherokee, Kansas. At the age of 12, he returned home to Fort Gibson.[5]

Upon returning home, Crawford Goldsby learned that his mother had remarried. After departing Fort Apache, on June 27, 1889, Ellen married William Lynch in Kansas City, Missouri, before proceeding to Fort Gibson. Lynch, born in Waynesville, Ohio, was a private in K Troop, 9th Cavalry. He had served during an earlier enlistment with H Troop, 10th Cavalry.[5] She was the "authenticated" laundress of the 10th Cavalry, D Troop, and stayed with the unit which gave her rations, transportation, and quarters. She transferred to Fort Davis, Texas, and to Fort Grant, Arizona. She was also with the unit at Fort Apache, Arizona.[5] Goldsby and William Lynch, his stepfather, did not get along. Crawford began to associate with unsavory characters, drink liquor, and rebel against authority.[5] By the time he was 15, Goldsby had moved in with his sister and her husband, Mose Brown, near Nowata, Oklahoma. However, Mose and his brother-in-law did not get along well, and Crawford did not stay for long. He went back to Fort Gibson, moved in with a man named Bud Buffington, and began working odd jobs.[5]

Life as an outlaw

editGoldsby's life as an outlaw began when he was 18. At a dance in Fort Gibson, Jake Lewis and he had a confrontation over a dispute that Lewis had with one of Goldsby's brothers. A few days later, Goldsby took a six-shooter and shot Lewis. Thinking Lewis was dead, Goldsby went on the run, leaving Fort Gibson and heading for the Creek and Seminole Nations, where he met up with outlaws Jim and Bill Cook, who were mixed-blood Cherokees.[5]

During the summer of 1894, the United States government purchased rights to a strip of Cherokee land and agreed to pay out $265.70 (~$9,357 in 2023) to each person who had a legal claim. Since Goldsby and the Cook brothers were Cherokee Nation citizens, they headed out to Tahlequah, Oklahoma, capitol of the Cherokee Nation, to get their money.[5]

At this time, Goldsby was wanted for shooting Lewis, while Jim Cook was wanted on larceny charges. The men did not want to be seen by the authorities, so they stopped at a hotel and restaurant run by an acquaintance, Effie Crittenden. They coaxed her go to Tahlequah to get their money. On her way back, she was followed by Sheriff Ellis Rattling Gourd, who hoped to capture Goldsby and the Cooks.[5] On June 17, 1894, Sheriff Rattling Gourd and his posse got into a gunfight with Goldsby and the Cook brothers. One of Gourd's men, Deputy Sequoyah Houston,[6] was killed, and Jim Cook was injured. The authorities fled, but later on, when Effie Crittenden was asked if Goldsby had been involved, she stated that it was not Goldsby, but it was Cherokee Bill. After her statement, Crawford Goldsby got the nickname "Cherokee Bill"[5] and became known as one of the most dangerous men of the Indian Territory.[2]

After this, the Cooks and Goldsby formed the Cook Gang and began to terrorize Oklahoma. Between August and October, Goldsby and the Cooks went on a crime spree, robbing banks, stagecoaches, and stores, and mercilessly killing those who stood in their way. During this time, Goldsby's hair started to fall out due to a disease inherited from his grandfather. The disease left him with so little hair on his head, he decided to shave the remainder off.

Crimes involving Cherokee Bill

edit- On May 26, 1894, robbery of T.H. Scales Store, Wetumka, Oklahoma.[7] 35 cents was stolen.[8]

- On June 17, 1894, killing of Deputy Houston.[9]

- On July 4, 1894, Kansas and Arkansas Railroad brakeman Samuel Collins was shot through the bowels after ejecting a drunkard for trying to steal a ride at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; a tramp who was on the same car tried to run, was shot and died later;[10] the assailant was Crawford Goldsby; according to an 1896 account Collins apparently died as well.[11]

- On July 6, 1894, Mississippi Railway Station Agent A. L. "Dick" Richards of Nowata, Oklahoma,[12] was reportedly killed by Cherokee Bill of which he later boasted[13] but which he later denied.[14]

- On July 18, 1894, Goldsby and his gang robbed Wells-Fargo Express Company and the St Louis and San Francisco railroad[15] train at Red Fork.[16]

- On July 30, 1894, they robbed the Lincoln County Bank in Chandler, Oklahoma, and made off with $500, killing J. B. Mitchell in the process.[2][17]

- In September 1894,[18] Goldsby shot and killed his brother-in-law, Joseph "Mose" Brown, either over an argument about some hogs, or because he thought that Brown "..got more of the parental estate than was due him..."[19]

- On September 14, 1894, robbery of Parkinson's Store at Okmulgee, Oklahoma.[20]

- On October 9, 1894, robbery of Express Office and Depot at Chouteau, Oklahoma.[20]

- On October 20, 1894, train robbery at Correatta, Oklahoma.[20]

- On October 22, 1894, Goldsby and three others robbed the post office and Donaldson's Store at Watova, Oklahoma.[21]

- On November 8, 1894, when the men robbed the Shufeldt and Son General Store, Goldsby shot and killed Ernest Melton, who happened to enter the store during the robbery.[2]

- On December 23, 1894, Goldsby and an accomplice Jim French held up and robbed Nowata, Oklahoma, Station Agent Bristow of $190.00.[22]

Jail break

editBecause of the Melton murder incident, the authorities stepped up their pursuit for Goldsby and the Cook Gang. With the pressure on, the gang split up. Most of the men were captured or killed, but Goldsby managed to escape. When the authorities offered a $1300 reward for the capture of Goldsby, some of his acquaintances came forward and agreed to help.[2]

On January 31, 1895, Goldsby was captured by Ike Rogers and Clint Scales in Nowata, Oklahoma; $1300 (~$47,611 in 2023)[24][25] and taken to Fort Smith, Arkansas, to wait for his trial.

On April 13, 1895, he was sentenced to death after being tried and convicted for the murder of Ernest Melton. However, his lawyer managed to postpone the execution date.

In June 1895 a pistol was discovered in a bucket at the Fort Smith jail; Goldsby claimed that a prison trustee named Ben Howell had brought the gun in and then had run away a few days later.[26]

In the meantime, Goldsby had made a friend, Sherman Vann, who was a trusty at the jail. Sherman managed to sneak a six-gun into Goldsby's cell, a Colt revolver.[27]

On July 26, 1895, Goldsby attempted a jail break with it. He jumped the night guards as they came to lock him into his cell. A guard, Lawrence Keating,[28] was shot in the stomach. As Keating staggered back down the corridor, Goldsby shot him again in the back. Other guards arrived and prevented Goldsby from escaping, but were not able to enter the jail either. Then another prisoner, Henry Starr, convinced the guards to let him go in and get Goldsby out. Moments later he came back with Goldsby, who was unarmed.

Hanging

editThe second trial lasted three days, resulting in a guilty verdict and U.S. District Judge Isaac C. Parker sentenced Goldsby to be hanged on September 10, 1895. A stay was granted, pending an appeal to the Supreme Court. On December 2, the Supreme Court affirmed the decision of the Fort Smith court and Judge Parker again set the execution date as March 17, 1896.[5]

On the morning of March 17, Goldsby awoke at six to have a smoke break. He ate a light breakfast sent from the hotel by his mother. At 9:20, his mother and "Aunty" Amanda Foster were admitted to his cell and shortly afterwards came Father Pius, a Catholic priest with whom he had been voluntarily meeting for the previous five days.[5]

The hanging was scheduled for 11 am, but was delayed until 2 pm so his sister Georgia could see him before the hanging. She was scheduled to arrive at 1 pm on the eastbound train.[5]

Shortly after 2 pm while on the gallows, it was reported Goldsby was asked if he had anything to say and he replied, "I came here to die, not make a speech." About 12 minutes later, Crawford "Cherokee Bill" Goldsby, the most notorious outlaw in the Territory, was dead.[5]

The body was placed in a coffin, which was placed in a box and taken to the Missouri Pacific depot. Placed aboard the train, Ellen and Georgia escorted the body to Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, for interment at the Cherokee National Cemetery.[5]

On April 20, 1897, Ike "Robinson" Rogers, who was reported to have been involved in the capture of Cherokee Bill, was shot and killed by Clarence Goldsby at Ft Gibson Oklahoma.[29][30]

In popular culture

editIn the 2021 film The Harder They Fall directed by Jeymes Samuel, the character of Cherokee Bill is played by actor Lakeith Stanfield.[31][32]

The role of Cherokee Bill was played by the actor Pat Hogan in a 1955 episode of the syndicated television series, Stories of the Century, starring and narrated by Jim Davis.[33]

References

edit- ^ "Lynch, Ellen Beck Goldsby (1859–1932)". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Weiser, Kathy. "Cherokee Bill - Terror of Indian Territory." September 2007. Legends of America. Accessed January 31, 2009.

- ^ "Search the Dawes Rolls, 1898–1914". Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Crawford (Cherokee Bill) Goldsby." Frontier Times.com. Accessed January 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u McRae, Bennie J. "Crawford "Cherokee Bill" Goldsby." Archived 2008-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Lest We Forget.com Accessed January 31, 2009.

- ^ ODMP Sequoyah Houston

- ^ ["The Coffeyville Daily Journal" Feb 19, 1913 .p.8 {Subecription website}]

- ^ ["Muskogee Phoenix" May 31, 1894 .p.5 {Subscription website}]

- ^ ODMP memorial Sequoyah Houston

- ^ [The Kokomo Tribune .p.1 July 4, 1894 {Subscription website}]

- ^ Indian Chieftain March 19, 1896 .p.2

- ^ ["Independence Daily Reporter" July 7, 1894 .p.1 {Subscription website}]

- ^ The Ohio Democrat February 9, 1895[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Sacramento Daily Union" March 18, 1896

- ^ Francisco Call, Volume 77, Number 59, 7 February 1895

- ^ Indian Chieftain November 15, 1894 .p.2 columon 4

- ^ The Guthrie Daily Leader August 1, 1894 p.1 column 1

- ^ LDs family Record

- ^ "Indian Chieftain" March 19, 1896 .p.2

- ^ a b c [The Coffeyville Daily Journal Feb 19, 1913 .p.8]

- ^ San Francisco Call, Volume 77, Number 74, 22 February 1895

- ^ The morning call., December 24, 1894, Page 2, Image 2 Library of Congress

- ^ Hell on the Border: He Hanged Eighty-eight Men. A History of the Great ...By S. W. Harman p.397

- ^ The Dallas daily Chronicle February 1, 1895

- ^ Credit for Cherokee Bills capture has also been credited to Constables James McBride and Henry Connelly. In December 1894 both officers had to stand trial on a compliant of assault by Cherokee Bill-they were obliged during the arrest to hit him over the head several times when he refused to release his teeth from McBride's thumb. A Jury acquitted both officers. See Indian Chieftain December 13, 1894 .p.4 column 2 Also repeated in "The Weekly Chieftain" Dec 13, 1894.p.4

- ^ ["The Coffeyville Daily Journal" July 30, 1895 .p.1 quoting "The Fort Smith Times"]

- ^ ["The Coffeyville Daily Journal" July 30, 1895 .p.1 quoting "The Fort Smith Times" reports Goldsby claimed the trusty in question was Ben Howell and that the pistol was .44. "The Wichita Daily Eagle" July 27, 1895 .p.1 reports that the pistol was a new pearl handled .41]

- ^ ODMP Lawrence Keating

- ^ The Daily Ardmoreite., April 21, 1897, Image 1

- ^ Indian chieftain., September 22, 1898, Image 2

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 12, 2021). "Netflix Unveils A 2021 Film Slate With Bigger Volume & Star Wattage; Scott Stuber On The Escalating Film Ambition". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10696784/ [user-generated source]

- ^ "Stories of the Century: "Cherokee Bill"". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

Further reading

edit- Kilpatrick, Jack F., and Anna G. Kilpatrick. Friends of Thunder: Folktales of the Oklahoma Cherokees. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8061-2722-8

- Burton, Arthur T. Black, Red, and deadly: Black and Indian gunfighters of the Indian territory. Eakin Press: Austin, TX, 1991. ISBN 0-89015-798-7