This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2022) |

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, pronounced Tsalagihi Ayeli[1]) was a legal, autonomous, tribal government in North America recognized from 1794 to 1907. It was often referred to simply as "The Nation" by its inhabitants. The government was effectively disbanded in 1907, after its land rights had been extinguished, prior to the admission of Oklahoma as a state.[2] During the late 20th century, the Cherokee people reorganized, instituting a government with sovereign jurisdiction known as the Cherokee Nation. On July 9, 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation (and by extension the Cherokee Nation) had never been disestablished in the years before allotment and Oklahoma Statehood.

Cherokee Nation ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ Tsalagihi Ayeli[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1794–1907 | |||||||||||||||||||||

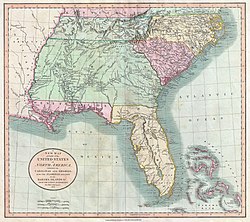

Southeastern U.S. and Indian territories, including Cherokee, Creek, and Chickasaw; 1806 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Sovereign state (1794-1865) United States region (1865-1907) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Cherokee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Autonomous tribal government | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Principal Chief | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1794–1907 | Principal Chief | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1794–1905 | Tribal Council | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-colonial to early 20th century | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Created with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse | 7 November 1794 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• New Echota officially designated capital city | 12 November 1825 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 December 1835 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Cherokee Trail of Tears | 1838–1839 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Tahlequah becomes new official capital | 6 September 1839 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Disbanded by U.S. Federal Government | 16 November 1907 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | US dollar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States -Oklahoma | ||||||||||||||||||||

The Cherokee Nation consisted of the Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ —pronounced Tsalagi or Cha-la-gee) people of the Qualla Boundary and the southeastern United States;[3] those who relocated voluntarily from the southeastern United States to the Indian Territory (circa 1820 —known as the "Old Settlers"); those who were forced by the Federal government of the United States to relocate (through the Indian Removal Act) by way of the Trail of Tears (1830s); and descendants of the Natchez, the Lenape and the Shawnee peoples, and, after the Civil War and emancipation of slaves, Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants. The nation was recognized as a sovereign government; because the majority of its leaders allied with the Confederacy, the United States required a new peace treaty after the American Civil War, which also provided for emancipation of Cherokee slaves. The territory was partially occupied by United States.

In the late 19th century, Congress passed the Dawes Act, intended to promote assimilation and extinguish Indian governments, but it exempted the Five Civilized Tribes. The Curtis Act of 1898 extended the provisions of the Dawes Act to the Five Tribes, in preparation for the admission of Oklahoma as a state in 1907. It provided for the distribution of tribal lands to individuals and also gave the federal government the authority to determine who were members of each tribe. The Curtis Act provided that residents of Indian Territory had voting rights in local elections.[4] Cherokee people, who were living in Indian Territory in 1901, were granted United States citizenship by virtue of a federal act (31 Stat. 1447) of March 3, 1901.[5]: 220 [6]: 12

History

editThe Cherokee called themselves the Ani-Yun' wiya. In their language; this meant "leading" or "principal" people. Before 1794, the Cherokee had no standing national government. Its people were highly decentralized and lived in bands and clans according to a matrilineal kinship system. The people lived in towns located in scattered autonomous tribal areas related by kinship throughout the southern Appalachia region. Various leaders were periodically appointed (by mutual consent of the towns) to represent the towns or bands to French, British and, later, United States authorities as was needed. The Cherokee knew this leader as "First Beloved Man"[7] —or Uku. The English had translated this as "chief".

The chief's function was to serve as focal point for negotiations with the encroaching Europeans. Hanging Maw was recognized as a chief by the United States government, but not by the majority of Cherokee peoples.[8]

At the end of the Cherokee–American wars (1794), Little Turkey was recognized as "Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation" by all the towns. At that time, Cherokee communities were on lands claimed by the states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and the Overhill area, located in present-day eastern Tennessee.

The break-away Chickamauga band (or Lower Cherokee), under War Chief Dragging Canoe (Tsiyugunsini, 1738–1792), had retreated to and inhabited a mountainous area in what later became the northeastern part of the future state of Alabama.[9]

U.S. president George Washington sought to "civilize" the southeastern American Indians, through programs overseen by US Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. Facilitated by the destruction of many Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War, U.S. land agents encouraged Native Americans to abandon their historic communal-land tenure and settle on isolated subsistence farmsteads. Over-harvesting by the deerskin trade had brought white-tailed deer in the region to the brink of extinction. Americans introduced pig and cattle raising, and these animals replaced deer as the principal sources of meat. The Americans supplied the tribes with spinning wheels and cotton-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land. (In the Cherokee traditional division of labor, most cultivation for farming was done by women.) Women were instructed in weaving. Eventually, blacksmiths, gristmills and cotton plantations (along with slave labor) were established.[10]

Succeeding Little Turkey as Principal Chief were Black Fox (1801–1811) and Pathkiller (1811–1827), both former warriors of Dragging Canoe. "The separation", a phrase which the Cherokee used to describe the period after 1776, when the Chickamauga had left other bands that were in close proximity to Anglo-American settlements, officially ended at the Cherokee reunification council of 1809.

Three important veterans of the Cherokee–American wars, James Vann (a successful businessman) and his two protégés, The Ridge (also called Ganundalegi or "Major" Ridge) and Charles R. Hicks, made up the younger 'Cherokee Triumvirate.' These leaders advocated acculturation of the people, formal education of the young, and introduction of European-American farming methods. In 1801 they invited Moravian missionaries to their territory from North Carolina to teach Christianity and the 'arts of civilized life.' The Moravian, and later Congregationalist, missionaries also ran boarding schools. A select few students were chosen to be educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions school in Connecticut.

These men continued to be leaders in the tribe. Hicks participated in the Red Stick War, a civil war between traditional and progressive Creek factions. This coincided with part of US involvement in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. He was the de facto principal chief from 1813–1827.

Constitutional governments

editThe Cherokee Nation—East had first created electoral districts in 1817. By 1822, the Cherokee Supreme Court was founded. Lastly, the Cherokee Nation adopted a written constitution in 1827 that created a government with three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Principal Chief was elected by the National Council, which was the legislature of the Nation. A similar constitution was adopted by the Cherokee Nation—West in 1833.

The Constitution of the reunited Cherokee Nation was ratified at Tahlequah, Oklahoma on September 6, 1839, at the conclusion of "The Removal". The signing is commemorated every Labor Day weekend with the celebration of the Cherokee National Holiday.

Removal

editIn 1802, the U.S. federal government promised representatives of the state of Georgia to extinguish Native American titles to internal Georgia lands in return for the state's formal cession of its unincorporated western claim (which was made part of the Mississippi Territory). Negotiating with states to give up western claims was part of the unfinished business from the American Revolution and establishing of the United States. European Americans were seeking more land in what became known as the Deep South because of the expansion of cotton plantations. Invention of the cotton gin had made short-staple cotton profitable, and it could be cultivated in the uplands of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in the Arkansaw district of the Missouri Territory and tried to convince the Cherokee to move there voluntarily. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. The Cherokee who moved to this reservation became known as the "Old Settlers" or Western Cherokee.[11]

By additional treaties signed with the U.S., in 1817 (Treaty of the Cherokee Agency, 8 July 1817) and 1819 (Treaty of Washington, 27 February 1819), the Cherokee exchanged remaining communal lands in Georgia (north of the Hiwassee River), Tennessee, and North Carolina for lands in the Arkansaw Territory west of the Mississippi River. A majority of the remaining Cherokee resisted these treaties and refused to leave their lands east of the Mississippi. Finally, in 1830, the United States Congress enacted the Indian Removal Act to bolster the treaties and forcibly free up title to the lands desired by the states. At this time, one-third of the remaining Native Americans left voluntarily, especially because the act was being enforced by use of government troops and the Georgia militia. Although The Treaty of New Echota was not approved by the Cherokee National Council nor signed by Principal Chief John Ross, it was amended and ratified in March 1836, and became the legal basis for the forcible removal known as the Trail of Tears.

Most of the settlements were established in the area around the western capital of Tahlontiskee (near present-day Gore, Oklahoma).

American Civil War and Reconstruction

editWithin the Cherokee Nation, there were advocates for neutrality, a Union alliance, and a Confederate alliance. Two prominent Cherokee, John Ross and Stand Watie were slaveholders and shared some values with Southern plantation owners. Watie thought it best for the Cherokee to side with the Confederacy, while Ross thought it better to remain neutral. This split was due to the Union's and Southern state's involvement of the Trail of Tears, which complicated the nation's political outlook. Within the first year of the war, general consensus in the nation moved towards siding with the Confederacy.[12]

Numerous skirmishes took place in the Trans-Mississippi area, which included the Cherokee Nation–West. There were seven officially recognized battles involving Native American units, who were either allied with the Confederate States of America or loyal to the United States government. 3,000 out of 21,000 members served as a soldier in the Confederacy.[13] Several prominent members of the Cherokee Nation made contributions during the war:

- William Penn Adair (1830–1880), a Cherokee senator and diplomat, served as a Confederate Colonel

- Nimrod Jarrett Smith, Tsaladihi (1837–1893), a future Principal Chief of the Eastern Band, also served during the war

- Confederate Brig. General Stand Watie (also known as Degataga, (1806–1871), a signer of the Treaty of New Echota) raided Union positions in the Indian Territory with his 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles Regiment of the Army of Trans-Mississippi well after the Confederacy had abandoned the area. He became the last Confederate general to surrender—on June 25, 1865.[14]

After the war, the United States negotiated new treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes. All Five Tribes acknowledged "in writing that, because of the agreements they had made with the Confederate States during the Civil War, previous treaties made with the United States would no longer be upheld, thus prompting the need for a new treaty and an opportunity for the United States to fulfill its goal of wrenching more land" from their grasp.[15] The new treaty established peace and requiring them to emancipate their slaves and to offer them citizenship and territory within the reservation if the freedmen chose to stay with the tribe, as the US had done for enslaved African Americans. The area was made part of the reconstruction of the former Confederate States overseen by military officers and governors appointed by the federal government.

A 2020 study contrasted the successful distribution of free land to former slaves in the Cherokee Nation with the failure to give former slaves in the Confederacy free land. The study found that even though levels of inequality in 1860 were similar in the Cherokee Nation and the Confederacy, former black slaves prospered in the Cherokee Nation over the next decades. The Cherokee Nation had lower levels of racial inequality where blacks saw higher incomes, higher literacy rates, and greater school attendance.[16]

Nation's demise

editIn 1898, the US Congress passed the Curtis Act which extended the Dawes Act of 1887 over the Five Civilized Tribes, forcing dissolution of tribally held lands in favor of individual allotments of private property.[17]: 161–162 It terminated the tribal courts, made tribal members subject to federal legislation, and gave the federal government the authority to determine tribal membership. The Curtis Act provided that residents of Indian Territory had voting rights in local elections and gave the federal government the right to incorporate towns and establish public educational facilities.[4] Under its terms tribal governments of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations would be abolished on March 6, 1906 in preparation for uniting Indian and Oklahoma Territories into the State of Oklahoma.[18] President Benjamin Harrison September 19, 1890, stopped the leasing of land in the Cherokee Outlet to cattlemen. The lease income had supported the Cherokee Nation in its efforts to prevent further encroachments on tribal lands.[19]

All Native people residing in Indian Territory were granted US citizenship under an act (31 Stat. 1447) of March 3, 1901.[5]: 220 [6]: 12 The Cherokee Nation entered an allotment agreement in 1902, which provided that each tribal citizen would receive forty acres as a homestead, which was untaxable and inalienable (ineligible to be sold) for twenty-one years, and seventy acres of surplus land which was inalienable for five years.[17]: 162 In response to these actions, the leaders of the Five Civilized Tribes sought to gain approval for a new State of Sequoyah in 1905 that would have a Native American constitution and government. The proposal received a cool reception in Congress and failed. The tribal government of the Cherokee Nation was dissolved in 1906. After this, the structure and function of the tribal government were not formally defined. The federal government occasionally designated chiefs of a provisional "Cherokee Nation", but usually just long enough to sign treaties.[20]

As the shortcomings of the arrangement became increasingly evident to the Cherokee, a demand arose for the formation of a more permanent and accountable tribal government. New administrations at the federal level also recognized this issue, and the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration gained passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, encouraging tribes to re-establish governments and supporting more self-determination. The Cherokee convened a general convention on 8 August 1938 in Fairfield, Oklahoma, to elect a new Chief and reconstitute the Cherokee Nation.[citation needed]

Indian Territory

editThe Cherokee Nation was divided into nine districts [1] named Canadian, Cooweescoowee, Delaware, Flint, Goingsnake, Illinois, Saline, Sequoyah, and Tahlequah (capital).

Cherokee capital

editFounded in 1838, Tahlequah was developed as the new capital of a united Cherokee Nation. It was named after the historic Great Tellico, an important Cherokee town and cultural center in present-day Tennessee that was one of the largest Cherokee towns ever established. The mostly European-American settlement of Tellico Plains later developed at the site. Indications of Cherokee influence found in and about Tahlequah. For example, street signs appear in both the Cherokee language—in the syllabary alphabet created by Sequoyah (ca. 1767–1843)[22]—and in English.

Cherokee National Capitol

editDesigned by architect C. W. Goodlander in the 'late Italianate' style, the Cherokee National Capitol was constructed between 1867 and 1869.[23] Originally, it housed the nation's court as well as other offices. In 1961, the US Department of Interior designated it a National Historic Landmark.[23][24][25]

People

editThe Nation was made up of scattered peoples mostly living in the Cherokee Nation–West and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (both residing in the Indian Territory by the 1840s), and the Cherokee Nation–East (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians); these became the three federally recognized tribes of Cherokee in the 20th century.

The Delaware

editIn 1866, some Delaware (Lenape) were relocated to the Cherokee Nation from Kansas, where they had been sent in the 1830s. Assigned to the northeast area of the Indian Territory, they united with the Cherokee Nation in 1867. The Delaware Tribes operated autonomously within the lands of the Cherokee Nation.[26]

Natchez people

editThe Natchez are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area. The present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi developed in their former territory. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Natchez people were defeated by French colonists and dispersed from there. Many survivors had been sold (by the French) into slavery in the West Indies. Others took refuge with allied tribes, one of which was the Cherokee.

The Shawnee

editKnown as the Loyal Shawnee or Cherokee Shawnee, one band of Shawnee people relocated to Indian Territory with the Seneca people (Iroquois) in July 1831. The term "Loyal" came from their serving in the Union army during the American Civil War. European Americans encroached and settled on their lands after the war.

In 1869, the Cherokee Nation and Loyal Shawnee agreed that 722 of the Shawnee would be granted Cherokee citizenship. They settled in Craig and Rogers counties.[27]

Swan Creek and Black River Chippewa

editThe Anishinaabe-speaking Swan Creek and Black River Chippewa bands were removed from southeast Michigan to Kansas in 1839. After Kansas became a state and the Civil War ended, European-American settlers pushed out the Native Americans. Like the Delaware, the two Chippewa bands were relocated to the Cherokee Nation in 1866. They were so few in number that they eventually merged with the Cherokee.

Cherokee Freedmen

editThe Cherokee Freedmen were former African American slaves who had been owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period. In 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation which granted citizenship to all freedmen in the Confederate States, including those held by the Cherokee. In reaching peace with the Cherokee, the U.S. government required the freedom of their slaves and full Cherokee citizenship for those who wanted to stay with the nation. This was later guaranteed in 1866 under a treaty with the United States.[28]

Notable Cherokee Nation citizens

editThis list of historic people includes only documented Cherokee living in, or born into, the original Cherokee Nation who are not mentioned in the main article:

- Elias Boudinot, Galagina (1802–1839), statesman, orator, and editor; founded the first Cherokee newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Assassinated by opponents for signing the New Echota Treaty to cede lands in the East.

- Ned Christie (1852–1892), statesman, Cherokee Nation senator, infamous outlaw[29]

- Rear Admiral Joseph J. Clark (1893–1971), United States Navy, highest-ranking Native American in US military history.

- Doublehead, Taltsuska (d. 1807), a war leader during the Cherokee–American wars, led the Lower Cherokee, and signed land deals with the U.S.

- Junaluska (ca. 1775–1868), a veteran of the Creek War, who saved President Andrew Jackson's life.

- John Ridge, Skatlelohski (1792–1839), son of Major Ridge, statesman and signer of New Echota Treaty signer, assassinated by opponents.

- John Rollin Ridge, Cheesquatalawny, or "Yellow Bird" (1827–1867), grandson of Major Ridge, first Native American novelist.

- Clement V. Rogers (1839–1911), Cherokee senator, judge, cattleman, member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

- Will Rogers, (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) Cherokee entertainer, roper, journalist, and author.[30]

- John Ross, Guwisguwi (1790–1866), a veteran of the Red Stick War, Principal Chief in the east during Removal, and in the west.

- Redbird Smith (1850–1918), traditionalist, political activist, and chief of the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society.

- William Holland Thomas, Wil' Usdi (1805–1893), non-Native who was adopted into the tribe, founding Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, commanding officer of the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders.

- Nancy Ward, Nanye-hi (ca. 1736–1822/4), Beloved Woman, diplomat.

In popular culture

edit- Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian) (or the Cherokee Nation song) by Paul Revere & the Raiders tells of the plight of the Cherokee Nation.[31]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b The James Scrolls

- ^ "Cherokee People". www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Indians, Eastern Band of Cherokees of North Carolina;" Donaldson, Thomas; 1892; 11th Census of the United States; Robert P. Porter, Superintendent, U.S. Printing Office, Washington, D.C.; published online at Eastern Band of Cherokees of North Carolina; retrieved October 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Lawson, Benjamin A. (2019). "Curtis Act". In Lawson, Russell M.; Lawson, Benjamin A. (eds.). Race and Ethnicity in America: From Pre-Contact to the Present. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1-4408-5097-4.

- ^ a b Ballinger, Webster (1915). "Statement of Mr. Webster Ballinger, Washington, D.C.". In McLaughlin, James (ed.). Enrollment in the Five Civilized Tribes: Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, House of Representatives. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 202–284. OCLC 682114627.

- ^ a b Wright, J. George (30 June 1904). "Previous Conditions and Recent Legislation". Annual Report of the United States Indian Inspector for the Indian Territory. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office: 9–12. OCLC 6733649.

- ^ Stanley W. Hoig, The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire, University of Arkansas Press, 1999, pp. 36, 37, 80

- ^ A Small Lexicon of Tsalagi words at Web Citations; A Few Words in Cherokee/Tsalagi; Tsalagi resources; access date January 18, 2010.

- ^ Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Dragging Canoe"; Journal of Cherokee Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 170–190; (Cherokee: Museum of the Cherokee Indian); 1977.

- ^ Perdue, Theda. Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1999. ISBN 978-0-8032-8760-0.

- ^ Lowery, Charles D. "The Great Migration to the Mississippi Territory, 1798–1819," Journal of Mississippi History, 1968 30(3): 173–192

- ^ "How the Cherokee Fought the Civil War". Ict News. Mar 27, 2012. Retrieved Sep 10, 2020.

- ^ Hauptman, Laurence M. (1995). "The General, The Western Cherokee and the Lost Cause". Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War. The Free Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780029141809.

- ^ Confer, Clarissa; The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War; University of Oklahoma Press; 2007; pg. 4.

- ^ Roberts, Alaina E. (2021). I've been here all the while : Black freedom on Native land. Philadelphia. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-8122-9798-0. OCLC 1240582535.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Miller, Melinda C. (2019-06-26). ""The Righteous and Reasonable Ambition to Become a Landholder": Land and Racial Inequality in the Postbellum South". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 102 (2): 381–394. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00842. ISSN 0034-6535.

- ^ a b Denson, Andrew (2017). Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-3083-0.

- ^ Wilson, Linda D. (2002). Everett, Dianna (ed.). "Statehood Movement". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Stillwater, Oklahoma: Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma State University Library Electronic Publishing Center. OCLC 181340478. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Rennard Strickland, "Cherokee (tribe)," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed April 18, 2015.

- ^ Cherokee Archived October 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine; article; Oklahoma Historical Society; "Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture."

- ^ Moser, George W. A Brief History of Cherokee Lodge #10., Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ Sequoyah Archived 2007-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, "New Georgia Encyclopedia"; retrieved 8 Aug 2010.

- ^ a b Francine Weiss (1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Cherokee National Capitol" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (pdf) on May 25, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Cherokee National Capitol". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service, added = October 15, 1966. Archived from the original on 2009-12-14. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ McCollum, Timothy James. Delaware, Western. Archived 2008-12-24 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture.. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^ Smith, Pamela A. "Shawnee Tribe (Loyal Shawnee)." Archived 2009-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Halliburton, R., Jr.: Red over Black – Black Slavery among the Cherokee Indians, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 1977 ISBN 978-0-8371-9034-1

- ^ "The Case of Ned Christie", Fort Smith Historic Site, National Park Service. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ Carter JH. "Father and Cherokee Tradition Molded Will Rogers". Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Jancik, Wayne The Billboard Book of One-Hit Wonders 1998. ISBN 0-8230-7622-9 page 247

Further reading

edit- Gen. Stand Watie, Confederate Indians (Univ. of Oklahoma, 1998)

External links

edit- Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the official site

- United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the official site

- Cherokee Heritage Center, Park Hill, OK

- Compiled laws of the Cherokee Nation, published by authority of the National Council = ᏗᎦᏟᏌᏅᎯ ᏗᎧᎿᏩᏛᏍᏗ ᏣᎳᎩ ᎠᏰᎵ ᏕᎤᎲᎢ, ᎠᏰᎵ ᏗᏂᎳᏫᎩᏱ ᎤᎵᏁᏨᎯ ᏗᎦᏃᏣᎶᏗᏱ. 1881