Rome is the largest city in and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses all of Floyd County. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 37,713. It is the largest city in Northwest Georgia and the 26th-largest city in the state.

Rome, Georgia | |

|---|---|

City | |

View of Rome from Myrtle Hill Cemetery | |

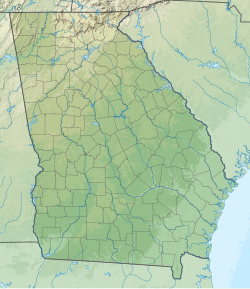

Location in Floyd County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 34°15′36″N 85°11′6″W / 34.26000°N 85.18500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Floyd |

| Incorporated | December 20, 1834 |

| Named for | Rome, Italy |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission–manager |

| • Commission | Members

|

| • Manager | Sammy Rich |

| Area | |

• City | 32.45 sq mi (84.05 km2) |

| • Land | 31.68 sq mi (82.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.77 sq mi (1.99 km2) |

| Elevation | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 38,255 |

| • Density | 1,190.40/sq mi (459.61/km2) |

| • Metro | 101,789 |

| • Demonym | Roman |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 30149, 30161, 30165 |

| Area code(s) | 706 and 762 |

| FIPS code | 13-66668[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0356504[5] |

| Major airport | CHA |

| Website | romega |

Rome was founded in 1834, after Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, and the federal government committed to removing the Cherokee and other Native Americans from the Southeast. It developed on former indigenous territory at the confluence of the Etowah and the Oostanaula rivers, which together form the Coosa River. Because of its strategic advantages, this area was long occupied by the historic Creek. Later the Cherokee people expanded into this area from their traditional homelands to the east and northeast. National leaders such as Major Ridge and John Ross resided here before Indian Removal in 1838.

The city has developed on seven hills with the rivers running between them, a feature that inspired the early European-American settlers to name it for Rome, that was also built on seven hills. The American Rome developed in the antebellum period as a market and trading city due to its advantageous location on the rivers. It shipped the rich regional cotton commodity crop downriver to markets on the Gulf Coast and export overseas.

In the late 1920s, a United States company built a rayon plant in a joint project with an Italian company. This project and the American city of Rome were honored by Italy in 1929, when Benito Mussolini sent a replica of the statue of Romulus and Remus nursing from a mother wolf, a symbol of the founding myth of the original Rome.[6]

It is the largest city near the center of the triangular area defined by the Interstate highways between Atlanta, Birmingham, and Chattanooga. It has developed as a regional center for the fields of medical care and education. In addition to its public-school system, it has several private schools. Higher-level institutions include private Berry College and Shorter University, and the public Georgia Northwestern Technical College and Georgia Highlands College.

History

editIndigenous history

editThe Abihka tribe of Creek in the area of Rome later became part of the Upper Creek people (who occupied the Northern Creek territory, called themselves the Muscogee). They merged with other Creek tribes to become the Ulibahali, who later migrated westward into Alabama in the general region of Gadsden.[7][8] By the mid-18th century, the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee had moved into this area and occupied it. They had moved down from areas of Tennessee, under pressure from settlement by Americans migrating across the Appalachians from eastern territories.

A Cherokee village named Etowah (Cherokee: ᎡᏙᏩ, romanized: Etowa), which means "Head of Coosa",[9][10] was settled in this area during the late 18th century, in the period of the Cherokee–American wars (1776–94) during and after the American Revolutionary War. Several Cherokee national leaders settled here and developed their own cotton plantations, including chiefs Major Ridge and John Ross. Some of the Cherokee planters and others among the Southeast tribes bought enslaved African Americans to use as laborers on such plantations.[11]

In the 20th century, Ridge's home here was preserved as Chieftain's House. It has been adapted by the state for use as the Chieftains Museum. It is used to interpret the history of the Cherokee in this area, especially Major Ridge.

In the 18th century, a high demand in Europe for American deerskins had led to a brisk trade between Indian hunters and White traders. A few White traders and some settlers (primarily from the Southern Colonies of Georgia and Carolina) were accepted by the Head of Coosa Cherokee. These were later joined by Christian missionaries, and more settlers. After the American War of Independence, most new settlers came from the area of Georgia east of the Proclamation Line of 1763.

In 1793, in response to a Cherokee raid into Tennessee, John Sevier, the Governor of Tennessee, led a retaliatory raid against the Cherokee in the vicinity of Myrtle Hill, in what was known as the Battle of Hightower.

In 1802, the United States and Georgia executed the Compact of 1802, in which Georgia sold its claimed western lands (a claim dating to its colonial charter) to the United States. In return, the federal government agreed to ignore Cherokee land titles and remove all Cherokee from Georgia. The commitment to evict the Cherokee was not immediately enforced, and Chiefs John Ross and Major Ridge led efforts to stop their removal, including several federal lawsuits.

During the 1813 Creek Civil War, most Cherokee took the side of the Lower Creek Indians, who were more assimilated and willing to deal with European Americans, against the Red Sticks or Upper Creek. As they had lived more isolated from the Whites, they had maintained strong, conservative cultural traditions. Before the Cherokee moved to Head of Coosa, Chief Ridge commanded a company of warriors as a unit of the Tennessee militia, with Chief Ross as adjutant. This Cherokee unit was under the overall command of United States Major Andrew Jackson, and supported the Upper Creek. They were the part of the Creek who had adopted more European-American customs and were more aligned with American settlers. The Creek War played out within the American Revolutionary War of the War of 1812.

In 1829, European Americans discovered gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, starting the first gold rush in the United States. Congressional passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which fulfilled the Compact of 1802, was related to that gold discovery and the desire of Whites to settle the land, as well as President Andrew Jackson's commitment to removal of Native Americans to enable development by the whites.

Even before removal began, in 1831, Georgia's General Assembly passed legislation that claimed all Cherokee land in Northwest Georgia. This entire territory was called Cherokee County; the following year, the Assembly organized the territory as the nine counties that still exist in the 21st century.[12][13]

City founding period

editRome was founded in 1834 as European Americans increasingly settled in Georgia. Founders were Col. Daniel R. Mitchell, Col. Zacharia Hargrove, Maj. Philip Hemphill, Col. William Smith, and John Lumpkin (nephew of Governor Lumpkin); most were veterans of the War of 1812. They held a drawing at Alhambra to determine the name of the new city, with Col. Mitchell submitting the name of Rome because of the area's hills and rivers.[14] Mitchell's submission was drawn, and the Georgia Legislature chartered Rome as an official city in 1835. The county seat was subsequently moved east from the village of Livingston to Rome.[15]

With the entire area still occupied primarily by Cherokee, the city developed to serve the agrarian needs of the new cotton-based economy. Invention of the cotton gin in the late 18th century made processing of short-staple cotton profitable. This was the type of cotton that best thrived in the upland areas, in contrast to that grown on the Sea Islands and in the Low Country.

Much of upland Georgia was developed as what became known as the Black Belt, named for the fertile soil. Planters brought or purchased many enslaved African Americans as workers for the labor-intensive crop. The leading Cherokee participated in the cultivation of cotton as a commodity crop, which soon replaced deerskin trading as a source of wealth in the region. The first steamboat navigated the Coosa River to Rome in 1836, reducing the time-to-market for the cotton trade and speeding travel between Rome and New Orleans on the Gulf Coast, the major port for export of cotton.

By 1838, the Cherokee had run out of legal options in resisting removal. They were the last of the major Southeast tribes to be forcibly moved to the Indian Territory (in modern-day Oklahoma) on the Trail of Tears. After the removal of the Cherokee, their homes and businesses were taken over by Whites, with much of the property distributed through a land lottery.

The Rome economy continued to grow. In 1849, an 18-mile (29 km) rail spur to the Western and Atlantic Railroad in Kingston was completed, significantly improving transportation to the east. This route was later followed in the 20th-century construction of Georgia Highway 293.[16] By 1860 the population had reached 4,010 in the city, and 15,195 in the county.

Civil war period

editRome's iron works were an important manufacturing center during the Civil War, supplying many cannons and other armaments to the Confederate effort. In April 1863, the city was defended by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest against Union Colonel Abel Streight's "lightning mule" raid from the area east of modern-day Cedar Bluff, Alabama.[17] General Forrest tricked Colonel Streight into surrendering just a few miles shy of Rome. Realizing their vulnerability, Rome's city council had allocated $3,000 to build three fortifications. Although these became operational by October 1863, efforts to strengthen the forts continued as the war progressed. These forts were named after Romans who had been killed in action: Fort Attaway was on the western bank of the Oostanaula River, Fort Norton was on the eastern bank of the Oostanaula, and Fort Stovall was on the southern bank of the Etowah River. The Confederates later built at least one other fort on the northern side of the Coosa River.[18][19]

In May 1864, Union General Jefferson C. Davis, under the command of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, attacked and captured Rome when the outflanked Confederate defenders retreated under command of Major General Samuel Gibbs French.[20] Union General William Vandever was stationed in Rome and is shown with his staff in a photograph taken there.[21] Due to Rome's forts and iron works, which included the manufacture of cannons, Rome was a significant target during Sherman's march through Georgia to take and destroy Confederate resources.[22] Davis' forces occupied Rome for several months,[23] making repairs to use the damaged forts and briefly quartering General Sherman. On November 11, 1864, in accordance with Sherman's Special Field Orders, No. 120, Union forces destroyed Rome's forts, iron works, the rail line to Kingston, and any other materiel that could be useful to the South's war effort as they withdrew from Rome to participate in Sherman's March to the Sea.[24]

Reconstruction era and 19th century

editIn 1871, Rome constructed a water tank on Neely Hill, which overlooks the downtown district. This later was adapted as a clock tower visible from many points in the city. It has served as the town's iconic landmark ever since, and is featured in the city's crest and local business logos. As a result, Neely Hill is also referred to as Tower or Clock Tower Hill.

During Reconstruction, the state legislature authorized public schools in 1868 for the first time, and designated some funding to support them. The city established its first public schools. Schools were racially segregated and tended to have short sessions, because of limited funding. In addition, many families depended on their children to work in agriculture and other basic survival work. Freedmen had been granted the franchise and tended to join the Republican Party of President Abraham Lincoln, who had freed them. The abolition of slavery required new labor arrangements to arrange for paid labor.

Due to its riverside location, Rome has occasionally suffered serious flooding. The flood of 1886 inundated the city to such depth that a steamboat traveled down Broad Street.[16] In 1891, upon recommendation of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Georgia State Legislature amended Rome's charter to create a commission to oversee the construction of river levees to protect the town against future floods.[25] In the late 1890s, additional flood control measures were instituted, including raising the height of Broad Street by about 15 feet (4.6 m). As a result, the original entrances and ground-level floors of many of Rome's historic buildings became covered over and had to serve as basements.[26]

Twentieth century

editIn the early 20th century, the Georgia Assembly approved a charter for the city to establish a commission-manager form of government, a reform idea to add a management professional to the team.

In 1928, the American Chatillon Company began construction of a rayon plant in Rome; it was a joint business effort with the Italian Chatillon Corporation. Italian premier Benito Mussolini sent a block of marble from the ancient Roman Forum, inscribed "From Old Rome to New Rome", to be used as the cornerstone of the new rayon plant. After the rayon plant was completed in 1929, Mussolini honored the American Rome with a bronze replica of the sculpture of Romulus and Remus nursing from the Capitoline Wolf. The statue was placed in front of City Hall on a base of white marble from Tate, Georgia, with a brass plaque inscribed:

This statue of the Capitoline Wolf, as a forecast of prosperity and glory, has been sent from Ancient Rome to New Rome during the consulship of Benito Mussolini in the year 1929.

In 1940, anti-Italian sentiment due to World War II became so strong that the Rome city commission moved the statue into storage to prevent vandalism.[6] They replaced it with an American flag. In 1952, the city restored the statue to its former location in front of City Hall.[27]

Great Depression

editIn Rome, the effect of the Great Depression was significantly less severe than in other, larger cities across the United States. Since Rome was an agricultural town, food could be grown in surrounding areas. Rome's textile mill continued operating, providing steady jobs for whites as a buffer against the economic hardships of the Great Depression.[28]

The Great Depression was preceded by the "Cotton Bust" across the South. This reached Rome in the mid-1920s, and caused many farmers to move away, sell their land, or convert to other agricultural crops, such as corn. Farm workers were displaced, and many African Americans left the area in the Great Migration, seeking work in cities, including those in the North and Midwest. Cotton crops were being destroyed by the boll weevil, a tiny insect that reached Georgia in 1915 (invading from Louisiana).[29] The boll weevil destroyed many fields of cotton and suppressed Rome's economy.

Many families struggled through hard financial times. Jobs were scarce, and prices of food and basic commodities went up. The federal "postal employees took a fifteen per cent cut in pay, and volunteered a further ten per cent reduction in work time to save the jobs of substitute employees who otherwise would have been thrown out of work."[30] Among fundraising activities for the poor, wealthier residents bought tickets to a show put on by local performers; the fares were paid to grocers, who made boxes of food to sell at a discount price to needy families.[31]

In a private "works project" to provide employment to men out of work, S.H. Smith Sr. decided to replace the Armstrong Hotel. After demolishing it, he employed many people to help build the towering Greystone Hotel at the corner of Broad and East Second streets. The Rome News-Tribune reported on November 30, 1933, an increase in local building permits for a total of $95,800; of this amount, $85,000 were invested by S.H. Smith Sr. in the construction of the Greystone Hotel. He added the Greystone Apartments in 1936.[32]

Geography

editRome is located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.[33] It is located at the confluence of the Etowah and the Oostanaula rivers, which form the Coosa River. This gave the city access to the waterways, the major transportation routes of the era. Because of this water feature, Rome developed as a regional trade center, based originally on King Cotton. As cotton plantations were developed in the area, Rome was an increasingly important market town, shipping the commodity downriver to other markets.[34] It was designated as the county seat of Floyd County.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 31.6 square miles (81.9 km2), of which 30.9 square miles (80.1 km2) are land and 0.73 square miles (1.9 km2), or 2.29%, are covered by water.[35]

The seven hills that inspired the name of Rome are known as Blossom, Jackson, Lumpkin, Mount Aventine, Myrtle, Old Shorter, and Neely Hills (the latter is also known as Tower or Clock Tower Hill). Some of the hills have been partially graded since Rome was founded.[36][37]

Climate

editThe climate in this area is characterized by relatively high temperatures and evenly distributed precipitation throughout the year. According to the Köppen climate classification, Rome has a humid subtropical climate, Cfa on climate maps.[38]

| Climate data for Rome, Georgia (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

85 (29) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

109 (43) |

105 (41) |

107 (42) |

99 (37) |

87 (31) |

80 (27) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 52.0 (11.1) |

56.1 (13.4) |

64.8 (18.2) |

73.7 (23.2) |

80.6 (27.0) |

86.5 (30.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

88.9 (31.6) |

83.8 (28.8) |

73.8 (23.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 41.1 (5.1) |

44.4 (6.9) |

51.9 (11.1) |

60.0 (15.6) |

68.0 (20.0) |

75.3 (24.1) |

78.8 (26.0) |

77.9 (25.5) |

72.2 (22.3) |

61.1 (16.2) |

50.3 (10.2) |

43.7 (6.5) |

60.4 (15.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 30.2 (−1.0) |

32.8 (0.4) |

39.0 (3.9) |

46.4 (8.0) |

55.3 (12.9) |

64.1 (17.8) |

67.9 (19.9) |

67.0 (19.4) |

60.5 (15.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

37.7 (3.2) |

33.1 (0.6) |

48.5 (9.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −9 (−23) |

−5 (−21) |

8 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

51 (11) |

51 (11) |

32 (0) |

23 (−5) |

4 (−16) |

−2 (−19) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.98 (126) |

4.81 (122) |

5.42 (138) |

4.88 (124) |

4.11 (104) |

4.79 (122) |

4.89 (124) |

4.20 (107) |

3.66 (93) |

3.78 (96) |

4.27 (108) |

5.30 (135) |

55.09 (1,399) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.4 (1.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.3 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 10.7 | 112.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Source: NOAA[39][40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 4,010 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,748 | −31.5% | |

| 1880 | 3,877 | 41.1% | |

| 1890 | 6,957 | 79.4% | |

| 1900 | 7,291 | 4.8% | |

| 1910 | 12,099 | 65.9% | |

| 1920 | 13,252 | 9.5% | |

| 1930 | 21,843 | 64.8% | |

| 1940 | 26,282 | 20.3% | |

| 1950 | 29,615 | 12.7% | |

| 1960 | 32,336 | 9.2% | |

| 1970 | 30,759 | −4.9% | |

| 1980 | 29,654 | −3.6% | |

| 1990 | 30,326 | 2.3% | |

| 2000 | 34,980 | 15.3% | |

| 2010 | 36,303 | 3.8% | |

| 2020 | 37,713 | 3.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[41] 1850-1870[42] 1870-1880[43] 1890-1910[44] 1920-1930[45] 1940[46] 1950[47] 1960[48] 1970[49] 1980[50] 1990[51] 2000[52] 2010[53] 2020[54] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop. 2000[55] | Pop. 2010[53] | Pop. 2020[54] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 20,704 | 18,974 | 17,971 | 59.19% | 52.27% | 47.65% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 9,638 | 9,991 | 10,020 | 27.55% | 27.52% | 26.57% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 78 | 88 | 77 | 0.22% | 0.24% | 0.20% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 494 | 690 | 742 | 1.41% | 1.90% | 1.97% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 25 | 17 | 10 | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.03% |

| Some other race alone (NH) | 43 | 73 | 134 | 0.12% | 0.20% | 0.36% |

| Mixed race or multi-racial (NH) | 378 | 578 | 1,340 | 1.08% | 1.59% | 3.55% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,620 | 5,892 | 7,419 | 10.35% | 16.23% | 19.67% |

| Total | 34,980 | 36,303 | 37,713 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 37,713 people, 14,169 households, and 8,870 families residing in the city.

2000 census

editAt the 2000 census,[56] 34,980 people, 13,320 households and 8,431 families were residing in the city. The population density was 1,190.5 inhabitants per square mile (459.7/km2). The 14,508 housing units averaged 493.7 per square mile (190.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 63.12% White, 27.66% African American, 1.42% Asian, 0.39% Native American, 0.16% Pacific Islander, 5.61% from other races, and 1.64% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 10.35% of the population.

Of the 13,320 households, 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living in them, 41.2% were married couples living together, 17.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.7% were not families. About 30.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47, and the average family size was 3.07.

The age distribution was 24.2% under the age of 18, 12.1% from 18 to 24, 27.7% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.2 males.

The median household income was $30,930, and the median family income was $37,775. Males had a median income of $30,179 versus $22,421 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,327. About 15.3% of families and 20.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.1% of those under the age of 18 and 16.3% of those 65 and older.

Economy

editRome has long had the strength of economic diversity, with an economy founded in manufacturing, education, healthcare, technology, tourism, and other industries.[57] In 1954, General Electric established a factory to build medium transformers. In the 1960s, Rome contributed to the American effort in the Vietnam War when the Rome Plow Company produced Rome plows, large armored vehicles used by the U.S. military to clear jungles. In the latter part of the 20th century, many carpet mills prospered in the areas surrounding Rome.

Rome is also well known in the region for its medical facilities, particularly Floyd Medical Center, Redmond Regional Medical Center, and Harbin Clinic. Partnering with these facilities for physician development and medical education is the Northwest Georgia Clinical Campus of the Medical College of Georgia, which is part of Georgia Health Sciences University.

National companies that are part of Rome's technology industry include Brugg Cable and Telecom,[58] Suzuki Manufacturing of America,[59] automobile parts makers Neaton Rome[60] and F&P Georgia, Peach State Labs,[61] and the North American headquarters of Pirelli Tire.[62] Other major companies in Rome include State Mutual Insurance Company.

In March 2020, Kerry Group announced plans to build a food-manufacturing facility in Rome at a cost of $125 million, the company's largest ever capital investment.[63]

Arts and culture

editSites include:

- Martha Berry Museum, a museum honoring Martha Berry, the founder of Berry College

- Rome Area History Museum

- Chieftains Museum (Major Ridge Home), a museum of Cherokee history, honoring chief Major Ridge and other leaders

- Clock Tower, a clock tower museum

- Rome Symphony Orchestra, oldest symphony orchestra in the Southern United States[64]

Sites on the National Register of Historic Places listings in Floyd County, Georgia:

- Dr. Robert Battey House

- Berry Schools

- Between the Rivers Historic District

- Chieftains

- Double-Cola Bottling Company

- East Rome Historic District

- Etowah Indian Mounds

- Floyd County Courthouse

- Jackson Hill Historic District

- Joseph Ford House

- Lower Avenue A Historic District

- Main High School

- Mayo's Bar Lock and Dam

- On the Coosa River, 8 miles SW of Rome

- Mt. Aventine Historic District

- Myrtle Hill Cemetery

- Oakdene Place

- Rome Clock Tower

- South Broad Street Historic District

- Sullivan—Hillyer House

- Thankful Baptist Church

- U.S. Post Office and Courthouse

- Upper Avenue A Historic District

Sports

editSince 2003, Rome has been the home of the Rome Emperors, the High-A affiliate of the Atlanta Braves. The Rome Emperors compete in the South Atlantic League. According to numbers released in 2010, sports tourism is a major industry in Rome and Floyd County.[65] In 2010, sport events netted over $10 million to the local economy, as reported by the Greater Rome Convention and Visitors Bureau.[66][65] Of these, tennis tournaments accounted for over $6 million to the Rome economy in 2010.[65]

Rome hosted the NAIA Football National Championship from 2008 until 2013.[67]

Rome has hosted stages of the Tour de Georgia in 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007.

The Georgia Fire was an indoor football team that played in Rome as a member of the Professional Indoor Football League.[68]

In June 2021, Rome hosted the USATF outdoor track and field championships, which were held at Barron Stadium.

Government

editThe city of Rome commission-manager form of government was adopted in 1918. The city's charter as approved by the legislature authorized a nine-member City Commission and a five-member Board of Education, to be elected concurrently, on an at-large basis by a plurality of the vote. The city was divided into nine wards, with one city commissioner from each ward to be chosen in the citywide election. There was no residency requirement for Board of Education candidates.

In 1966, after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was passed, the city amended its charter with approval by the state legislature, reducing the number of wards from nine to three, with commission members to be elected by at-large voting to numbered positions, three for each ward, with three wards in total. Candidates were required to win by majority vote, with run-off elections between the top two candidates for each seat if no majority emerged after the first round of voting.

From 1964 to 1975, the legislature approved the city's 60 acts for annexations, which appropriated mostly areas with white-majority populations.[citation needed][clarification needed]

At the same time, the board of education was increased to six members elected from three wards, with two numbered positions to be elected at-large from the city for each ward, A majority vote was required to win, with runoff procedures to apply to the top two candidates if no majority was achieved. A residency requirement was added for the board members.

This entire proposal was subject to review under the VRA. The city challenged the attorney general's authority to reject the annexation and electoral systems for each, as plaintiffs believed the reduction in seats and requirement for majority ranking to win would dilute the voting power of the African-American minority. In 1970, the city had a population of 30,759, with an ethnic composition of 76.6% White and 23.4% Black. Under the state constitution and previous practices making voter registration difficult, African Americans had been essentially disenfranchised since the turn of the 20th century.

In City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980), the US Supreme Court ruled on the city's argument that the attorney general had acted incorrectly in failing to approve the city's changes to its election system and its annexations. (The city did not seek pre-clearance of its charter changes to its election system in 1966, nor did it get approval of its 60 annexations from November 1, 1964, to February 10, 1975, which were both required under the law.)

The court upheld the constitutionality of the act, including the prohibition of unintentional discrimination to mitigate the potential that a jurisdiction may engage in intentional discrimination. Because of these findings, the court affirmed the lower court ruling.

In the 2000 census, White Americans made up 63.12% of the population, African Americans made up 27.66% of the city's population, and other minorities comprised the remainder. A total of 10.36% of residents identified as Hispanics of any race. The nine-member commission elects a mayor and vice mayor from among its members for specific terms. In addition, the commission hires a city manager for daily operations.

Commission members are elected at-large from three wards of the city; each ward has three seats on the commission. All voters vote for candidates for each position; and candidates may be elected by plurality voting. Members are elected for four-year staggered terms, with commissioners from wards 1 and 3 elected at the same time, and commissioners from ward 2 two years later.[69]

Education

editPublic schools

editThe Rome City School District, which serves the whole city limits,[70] holds grades preschool to grade 12, operating seven elementary schools, North Heights having shut down in 2019/2020.[citation needed] It has two secondary schools, Rome Middle School, and Rome High School.[71] The district has 323 full-time teachers and more than 5,395 students.[72]

The Floyd County School District is for families outside the city limits.[70] Two of its high schools are not in the city limits but have Rome postal addresses: Armuchee High School and Coosa High School.

Private schools

editRome has several private schools:

- Darlington School is a coeducational, college-preparatory day and boarding school established in 1905. It offers classes ranging from Pre-K to grade 12, divided into lower, middle, and upper schools.

- Unity Christian School is a private, Christian school established in 1998. It offers classes ranging from Pre-K to grade 12 with two classes per grade level.

- Berry College Elementary and Middle School offers the resources and expertise of a liberal-arts college faculty.[73]

- Montessori School of Rome is a coeducational school that follows the Montessori curriculum for all grades. It opened in 1980. It offers classes for Pre-K to 12th.

- Providence Preparatory Academy offers kindergarten through the grade 11, as of 2015, and plans to complete adding grades to the 12th year.

- St. Mary's Catholic School, established in 1945, offers Pre-K through eighth grade, with two classes per grade level.

Higher education

editRome is home to four colleges:

| College | Public/ private |

Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berry College | Private | Liberal arts | Founded in 1902 by Martha Berry |

| Georgia Northwestern Technical College | Public | Technical college | Formerly "Coosa Valley Technical College," founded in 1962 |

| Georgia Highlands College | Public | State college | Formerly Floyd Junior College |

| Shorter University | Private | Liberal arts | Formerly Shorter College, founded in 1873 |

Media

editFilm production

editFeature films

edit| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | King Cotton | Silent documentary[74][75] |

| 1979 | The Double McGuffin | Filming took place at Berry College and Darlington School.[75] |

| 1986 | The Mosquito Coast | The film features scenes from Rome and Cartersville, Georgia, representing a fictional city in Massachusetts. Visible from Rome are the historic Floyd County Courthouse and Oostanaula River.[75] |

| 1991 | Dutch | The comedy features several scenes shot at Berry College and elsewhere in Rome.[75] |

| 2000 | Remember the Titans | The film was shot partly on the Berry College campus.[75] |

| 2001 | The Substitute 4: Failure Is Not an Option | The direct-to-video film was shot in different locations around Georgia, including Rome.[75][76] |

| 2002 | Sweet Home Alabama | The romantic comedy was filmed partially on the Berry College campus, prominently featuring the former Martha Berry residence, the Oak Hill Berry Museum. Scenes were also shot at the Coosa Country Club.[75] |

| 2004-05 | Sugar Creek Gang (series) | All five films based on the children's book series of the same name were filmed in Rome.[75] |

| 2005 | The Derby Stallion | [75] |

| 2006 | Dark Remains | The horror movie was filmed almost entirely at the Floyd County Prison.[75] |

| Big Red: The Ghost of Floyd County Prison | This documentary was filmed alongside the production of Dark Remains. It chronicles a ghost story from the Floyd County Prison.[75][77] | |

| 2007 | Freelance | [75] |

| 2008 | Dance of the Dead | An independent zombie comedy filmed at various locations in Rome and North Georgia, including the old Coosa Middle School, Myrtle Hill Cemetery, Shorter College, and the Claremont House[75][78][79] |

| Dangerous Calling | [75] | |

| Golgotha | Scenes for the film were shot at Berry College.[75][80] | |

| 2009 | Lonely Love | [75][81] |

| Theater of the Mind | A documentary about the history of the Golden Age of Radio, it shot scenes in Rome.[82] | |

| Lynch Mob | [75][83] | |

| Di passaggio | Documentary film which shot scenes on the Berry College Campus[84] | |

| 2012 | Revenge of the Sandman | Low-budget horror film that was shot partly in Rome[85] |

| All Hallows Evil: Lord of the Harvest | Low-budget horror film that was shot partly in Rome[75][86] | |

| 2013 | Identity Thief | Select "street scenes" were filmed in Rome.[87] |

| Butch Walker: Out of Focus | Documentary film about the life of Butch Walker[75] | |

| 2014 | Need for Speed | Scenes for the film were shot at Myrtle Hill Cemetery and in rural Floyd County near Cave Spring, Georgia.[75][88] |

| The System | [75] | |

| Blind Tiger: The Legend of Bell Tree Smith | [75][89] | |

| 2015 | Ivide | Scenes for the film were shot at Rome Cinemas on March 6, 2015.[90] |

| 2021 | Black Widow | Scenes of the film were shot in 2019 at South Broad Street, Chuck's Corner,[91] and Barron Stadium.[92] |

| 2022 | Spirit Halloween: The Movie | Scenes of the film were shot at the DeSoto Theater, Celanese Mill, and a former Toys R Us store.[93] |

| 2023 | You're Killing Me | 80% of filming was conducted at a home near Horseleg Creek Road.[94] |

Short films

edit- The Bread Squeezer (2006)[75][95]

- Capitalism Rocks! (2006)[75][96]

- Apparition Point (2007)[75][97]

- Death Waits (2009)[75][98]

- The Other Half (2009)[75][99]

- Der Gries (2010)[75][100]

- Storage (2011), filmed at Berry College[101]

- Next of Kin (2012)[102]

- The Design (2014)[103]

Television production

edit| Year | Title | Episode(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | The Baron and the Kid | — | Starring Johnny Cash, the television film was shot in both Rome and Cedartown, Georgia.[75][104] |

| 1991 | Perfect Harmony | A television film, it features several scenes shot at Berry College.[75] | |

| 1993 | Class of '61 | A television film[75] | |

| 2000 | Ford commercial | [75] | |

| 2005 | Rezoned | 1.05 "Louisville Bookstore, Georgia Pants Factory, Key West Hotel, Idaho High School" | Episode features the former Rome Manufacturing Company & Coosa Pants Factory in downtown Rome, now a family home.[105] |

| 2009 | 16 and Pregnant | 1.05: "Whitney" | The subject lives in Rome and attends Rome High School. |

| 2012 | Finding Your Roots | 1.07: "Samuel L. Jackson, Condoleezza Rice, and Ruth Simmons" | Stock footage of Rome's historic downtown is used in the opening scenes of the episode.[106] |

| 2012 | You Live in What? | — | Episode features the same factory, and now home, featured in the 2005 episode of Rezoned.[107] |

| 2013 | The Following | 1.01: "Pilot" | [75][108] |

| Beyond Scared Straight | 3.13: "Floyd County Jail, GA" | [109] | |

| 4.02: "Floyd County, GA: Deputy Lyle Returns" | [110] | ||

| 5.02: "Floyd County, GA: Snitches Get Stitches" | [111] | ||

| House Hunters | 78.08: "Nurse Makes Fresh Start on a Tiny Budget in Small Town Georgia" | [75][112][113][114] | |

| The Haves and the Have Nots | — | Filming for the production has taken place in Rome throughout the series.[75] | |

| 2014 | If Loving You Is Wrong | ||

| 2015 | Kingmakers | A television film and possible ABC series pilot, the film was produced by Loucas George and directed by James Strong. Filming started in March at Berry College and around Rome's historic downtown.[115] | |

| 2022 | Kindred | Filmed on Broad Street in Downtown Rome[116] | |

| 2022–2025 | Stranger Things | Several episodes of Season 4 and 5 were shot at the Claremont House.[117][118][119] |

Web-series

edit- My Mother/Agent (2010)[120]

Newspapers

editRadio stations

edit| Call letters | Frequency | Nickname | Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| WGPB | 97.7 FM | NPR | Public Radio |

| WLAQ | 1410 AM | n/a | Talk |

| WQTU | 102.3 FM | Q102 | Hot AC |

| WRGA | 1470 AM | n/a | News/Talk |

| WSRM | 93.5 FM | South 93.5 | Country |

| WROM | 103.1 FM | Radio M | Top 40 |

| WUKV | 95.7 FM | K-Love | Contemporary Christian |

| WRBF | 104.9 FM | 104.9 The Rebel | "Classic Rock, Southern style" |

| WGJK | 99.5 FM | K Country | Country |

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editHighways

editPedestrians and cycling

edit- Downtown River Trail

- Heritage Trail System

- Kingfisher Trail

- Oostanaula Levee Trail

- Silver Creek Trail

- Thornwood Trail

Rail transport

editUntil 1970, the Southern Railway operated the Royal Palm for passenger train service through Rome's Southern Railway Depot. Into the early 1960s the Royal Palm and the Ponce de Leon traveled a Cincinnati - Atlanta - Jacksonville route.[121][122]

Healthcare

editHospitals in Rome include Atrium Health Floyd, and AdventHealth Redmond.[123][124][125]

Notable people

edit- Adam Anderson (born 2001), former college football player

- Arn Anderson (birth name Martin Lunde) (born 1958), professional wrestler

- Bill Arp (birth name Charles H. Smith) (1826–1903), Rome mayor and 19th-century writer[126]

- Jamie Barton (born 1981), opera singer

- Charlie Culberson (born 1989), Major League Baseball player

- Ashley Diamond (born 1978), prison and LGBTQ rights activist

- Kris Durham (born 1988), American football player[127]

- Charles Fahy (1892–1979), U.S. Solicitor General and Navy Cross[128]

- Betty Fountain, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player[129]

- Benn Fraker (born 1989), canoeist[130][131]

- Mike Glenn (born 1955), NBA[132]

- Henley Gray (born 1933), racing driver

- Steve Gray (born 1956), racing driver

- Marjorie Taylor Greene (born 1974), conservative politician, businesswoman

- Ethel Hillyer Harris (1859–1931), author

- Betty Hester (1923–1998), literary correspondent[133]

- Ken Irvin (born 1972), professional football player[134]

- Albert E. Jarrell (born 1901), vice admiral, U.S. Navy

- Randy Johnson (born 1953), football player

- Chris Jones (born 1989), punter, National Football League, (Dallas Cowboys, 2011–present)

- Larry Kinnebrew (born 1960), professional football player[135]

- John H. Lumpkin (1812–1860), co-founder of Rome, Superior Court judge, and member of the U.S. House of Representatives[136]

- Homer V. M. Miller (1814–1896), U.S. senator, senior Confederate medical officer[137]

- George Stephen Morrison (1919–2008), admiral; father of singer Jim Morrison[138]

- Will Muschamp (born 1971), college football coach

- Willard Nixon (1928–2000), Major League Baseball player

- Robert Ernest Noble (1870–1956), U.S. Army major general[139]

- John Pemberton (1831–1888), inventor of Coca-Cola

- Ralph Presley (1930–2022), aviator and politician

- Ma Rainey (1886–1939), blues singer[140]

- Tate Ratledge (c. 2004), American football player

- Dan Reeves (1944–2022), American football player and head coach

- Major Ridge (c. 1771 – 1839), Cherokee chief and co-signer of the Treaty of New Echota

- John Ross (1790–1866), principal chief of the United Cherokee Nation

- Victaria Saxton (born 1999), WNBA

- Melanie Sumner (born 1963), novelist and writer

- John H. Towers (1885–1955), U.S. Navy admiral and pioneer Navy aviator

- Butch Walker (born 1969), rock and roll musician

- Nina B. Ward (1885–1944), artist who helped found the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts

- Stand Watie (1806–1871), Cherokee leader and Confederate general

- Ernest West (1867–1914), Georgia Tech's first football coach

- Calder Willingham (1922–1995), screenwriter and novelist

- Ellen L. A. Wilson (1860–1914), First Lady of the United States (1913–14) and first wife of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson[141]

Gallery

edit-

Aerial view of downtown Rome, circa 1989

-

Downtown Rome

-

Historic Floyd County Courthouse

-

Historic Clock Tower on Neely Hill

-

The Rome Area History Museum

-

Rome City Hall and Auditorium. The statue of Romulus and Remus nursing from the Capitoline Wolf stands in front of the building.

-

This house, built in 1892, at 315 East Fourth Street, was destroyed by a falling tree in April 2011.

-

The waterwheel of Berry College's Old Mill

-

Rome Town Green

-

Chief John Ross pedestrian bridge

-

Stained glass at St. Peter's Episcopal Church

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "City Manager's Office". RomeFloyd.com. Governments of Floyd County and City of Rome, GA. 2017. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "Rome City Commission". RomeFloyd.com. Governments of Floyd County and City of Rome, GA. 2017. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Rome, Georgia". www.census.gov. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Rome, Ga., Levels Statue Presented by Mussolini". The New York Times. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Waselkov, Gregory A., and Marvin T. Smith. "Upper Creek Archaeology", in McEwan, Bonnie G., ed. Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2000) p. 244-245

- ^ Ethridge, Robbie Franklyn, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: UNC Press) p. 27

- ^ "Rome". roadsidegeorgia.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Britannica, Encyclopedia. "Rome, Georgia, United States". www.britannica.com. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Rome City Commission Archives" (PDF). March 3, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008.

- ^ "Cherokee County Historical Maps". Georgia Info. Digital Library of Georgia. 2001. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Original Cherokee County Divided". Georgia Info. Digital Library of Georgia. May 28, 2001. Archived from the original on January 18, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Floyd County". Calhoun Times. September 1, 2004. p. 75. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Hart, Brett (July 1999). "Founders of Rome - Guide to Rome Georgia | RomeGeorgia.com". RomeGeorgia.com. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b McElwee, Bobby. "Rome, Georgia". Roadside Georgia. Golden Ink. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Willett, Robert L. (2011). "The Lightning Mule Brigade – Attack on Rome, Georgia". About North Georgia. Golden Ink. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ RomeGeorgia.com: Article on the history of Rome's forts. Archived November 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Fort Norton, Rome, Georgia". Roadside Georgia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Charles A. Dana and J. H. Wilson, The Life of Ulysses S. Grant, Gurdon Bill & Company, 1868, p. 275

- ^ Eicher & Eicher, Civil War High Commands, p. 542.

- ^ "Noble Brothers Foundry". Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 469. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Slay, David (2006). "Playing a Sinking Piano: The Struggle for Position in Occupied Rome, Georgia". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 90 (4): 483–504. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Welcome". Fort Attaway Preservation Society. Fort Attaway Preservation Society, Inc. 2009. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Acts Passed by the General Assembly of Georgia, Volume II. Atlanta, Georgia: Geo. W. Harrison, State Printer (Franklin Publishing House) 1892: Creating Levee Commission for Rome, Etc. No. 625 (pp. 585–590).

- ^ "Between the Rivers Historic District". Guide to Rome Georgia. RomeGeorgia.com. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Romulus and Remus Statue". Georgia Info. Digital Library of Georgia. 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Great Depression". New Georgia Encyclopedia. November 8, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ "Boll Weevil". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ Battey, George Magruder, 1887–1965 – A History of Rome and Floyd County, State of Georgia .. (Volume 1) Page 412

- ^ Battey, Page 409

- ^ Battey, pp. 412 and 415

- ^ Saslow, Eli (December 15, 2024). "The Alienation of Jaime Cachua". The New York Times.

- ^ Pullen, George (July 1, 2009). "Rome". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Rome city, Georgia". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ Boyd, Chris (July 1999). "The Seven Hills of Rome". RomeGeorgia.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2002. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Denmon, Shirley. The Enchanted Land Eighth Hill. (2012). pp. 5. ISBN 9781452089553

- ^ "Rome, Georgia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Rome, GA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Georgia - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1870.

- ^ "1880 Census of Population - Georgia - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1880.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1930.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1930. pp. 251–256.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1940.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1980.

- ^ "1960 Census of Population - Population of County Subdivisions - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1960.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Population of County Subdivisions - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1970.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1980.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Summary Social, Economic, and Housing Characteristics - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1990.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - General Population Characteristics - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2000.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Rome city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Rome city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Rome city, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Georgia - 2000 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). April 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ "Rome, Georgia" Archived October 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, New Georgia Encyclopedia

- ^ "Brugg Cable & Telecom". bruggcables.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "Suzuki Motor of America, Inc". Suzuki Motor of America, Inc. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "Home – Neaton Auto Products Manufacturing, Inc". neaton.com. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ "Peach State Labs, LLC". peachstatelabs.com. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "Pirelli Tire Manufacturing". Archived from the original on May 17, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ Taylor, Charlie. "Kerry Group to build $125m facility in US as FDI from Ireland jumps". The Irish Times. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "History RSO". History. romesymphony.org. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Rome tourism officials say visitors brought $9 million to area in 2010" Archived July 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Rome News-Tribune

- ^ "Georgia's Rome – Office of Tourism". Georgia's Rome Office of Tourism. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ "Visitor Info: Football National Championship". naia.org. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ PIFL welcomes Georgia Fire Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "City of Rome Organization" Archived April 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Rome/Floyd County website

- ^ a b "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Floyd County, GA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Schools in Rome city". Georgia Department of Education. Retrieved March 8, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Free District Report for Rome City". School-Stats.com. 2005. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Freygan, Andrea (June 18, 2007). "Berry Elementary to celebrate 30 year | Local New". Rome-News Tribune. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ "King Cotton". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai "Filming in Georgia's Rome". romegeorgia.org. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Substitute: Failure Is Not an Option". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Drak Remains – The Prison". darkremains.com. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Movie wants to film in Rome if school board grants use of the old Coosa Middle School". Rome News-Tribune. OME, ga. March 3, 2007.

- ^ "Dance of the Dead movie filmed in Rome to be released on DVD". Rome News-Tribune. Rome, GA. August 21, 2008.

- ^ "Golgotha (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Lonely Love (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Theater of the Mind (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Lynch Mob (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Di passaggio (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Revenge of the Sandman (2012) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "All Hallows Evil: Lord of the Harvest (2012) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Identity Thief (2013) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Need for Speed (2014) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Blind Tiger: The Legend of Bell Tree Smith (2014)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Stewart, Jeremy (March 7, 2015). "Cast, crew of 'Ivide' shoot scenes at movie theater: Film moves to Rome for a day". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Singh, Prerna (July 8, 2021). "Where Was Black Widow Filmed? All Black Widow Filming Locations". The Cinemaholic. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ DeLetter, Emily (July 9, 2021). "No spoilers, but 'Black Widow' is probably from Cincinnati like the rest of us". The Enquirer. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Druckenmiller, John (August 2, 2022). "The DeSoto, Celanese and former Toys R Us all have cameos in the just-released teaser trailer for 'Spirit Halloween: The Movie'". Northwest Georgia News. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ Druckenmiller, John (April 21, 2022). "That's a wrap: Filming with Anne Heche and Dermot Mulroney ends at Rome home". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Bread Squeezer (2006) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Capitalism Rocks! (2006) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Apparition Point (2007)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Death Waits (2009)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Other Half (2009) – Filming Locations". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Der Gries (2010)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Storage (2011)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Next of Kin (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Design (2014)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Baron and the Kid (1984)". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Episode Detail: Louisville Bookstore, Georgia Pants Factory, Key West Hotel, Idaho High School – Rezoned". TV Guide. November 6, 2005. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Full Episode: Samuel L. Jackson, Condoleezza Rice and Ruth Simmons". PBS. April 29, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Former Pants Factory". HGTV. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Following": Season 1, Episode 1 "Pilot". IMDb. January 21, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Beyond Scared Straight Episode Guide: Season 3". A&E. August 20, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Beyond Scared Straight Episode Guide: Season 4". A&E. May 30, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Beyond Scared Straight: Season 5, Episode 2". A&E. October 9, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Nurse Makes Fresh Start on a Tiny Budget in Small Town Georgia (includes correct episode number)". HGTV. September 23, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "House Hunters Episode Guide (includes airdate)". TV Guide. September 23, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Nurse Makes Fresh Start on a Tiny Budget in Small Town Georgia (includes full episode description)". HGTV (Canadian TV channel). September 23, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Walker, Doug (February 28, 2015). "TV movie "Kingmakers" to be filmed in Rome next month". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Downtown Rome Transforms to 1800s Era for Filming of FX Series Show". Coosa Valley News. June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia film industry bounces back from pandemic with record year". Northwest Georgia News. July 21, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, John (July 27, 2021). "Portion of Second Avenue closed until Thursday as 'Stranger Things' films". Northwest Georgia News. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Portions of Second Avenue closed all week as 'Stranger Things' films". Northwest Georgia News. June 3, 2024. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "My Mother/Agent (2010– )". IMDb. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Southern Railway, June 1952, Tables 4 and 10 http://streamlinermemories.info/South/SOU52TT.pdf

- ^ "Southern Railway, Table 5". Official Guide of the Railways. 96 (1). National Railway Publication Company. June 1963.

- ^ Walker, Doug; Bailey, John (July 14, 2021). "Merger between Floyd Health System and North Carolina-based Atrium Healthcare finalize". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, John (May 13, 2021). "AdventHealth signs $635 million agreement to buy Redmond Regional Medical Center". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Bailey, John (October 1, 2021). "Redmond sale to AdventHealth finalized". Rome News-Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Arp, Bill (1884). Bill Arp's Scrap Book: Humor and Philosophy. J.P. Harrison & Company.

- ^ "Kris Durham". National Football League.

- ^ Fahy, Charles (1937). Goal of National Labor Relations Act.

- ^ Betty Fountain Profile. All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Official Website.

- ^ "Benn FRAKER – Olympic Canoe Slalom | United States of America". International Olympic Committee. June 21, 2016.

- ^ "Racing to a Different Drummer". Canoe & Kayak Magazine. May 7, 2013.

- ^ "Mike Glenn Stats | Basketball-Reference.com". Basketball-Reference.com.

- ^ "O'CONNOR, FLANNERY. Letters to Betty Hester,1955–1964". Emory University Library.

- ^ "Ken Irvin Stats | Pro-Football-Reference.com". Pro-Football-Reference.com.

- ^ "Larry Kinnebrew Stats | Pro-Football-Reference.com". Pro-Football-Reference.com.

- ^ Hicks, Paul DeForest (February 2012). Joseph Henry Lumpkin: Georgia's First Chief Justice. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820340999.

- ^ "MILLER, Homer Virgil Milton – Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Archived from the original on September 1, 1999. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Grimes, William (December 8, 2008). "George S. Morrison, 89; Navy Commander and Father of Rock Singer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Hobson, Sarah, ed. (December 1918). "Biographical Summary, Robert E. Noble". Journal of the American Institute of Homœopathy. Chicago, IL: American Institute of Homeopathy. p. 591 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ma Rainey | American singer". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ "Ellen Wilson Biography :: National First Ladies' Library". firstladies.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

Further reading

edit- Roger Aycock, All Roads to Rome, Georgia: W. H. Wolfe Associates, 1981. Amazon.com

- George Magruder Battey Jr., A History of Rome and Floyd County, Georgia 1540–1922, Georgia: Cherokee Publishing Company, 2000. Amazon.com

- Morrell Johnson Darko, The Rivers Meet: A History of African-Americans in Rome, Georgia, Darko, 2003. Amazon.com

- Jerry R. Desmond, Georgia's Rome: A Brief History, Charleston: The History Press, 2008. Amazon.com

- Sesquicentennial Committee of the City of Rome, Rome and Floyd County: An Illustrated History, The Delmar Co 1986.Amazon.com

- Strong, Robert Hale (1961). Halsey, Ashley (ed.). A Yankee Private's Civil War. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. pp. 45–46. LCCN 61-10744. OCLC 1058411.

- Orlena M. Warner, When in Rome ... , Georgia: Steven Warner, 1972. A collection of poems. Amazon.com