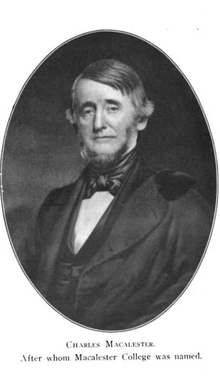

Charles Macalester (February 17, 1798 – December 9, 1873) was an American businessman, banker and philanthropist from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He served as a government director for the Second Bank of the United States and an advisor and friend to several U.S. presidents. His brokerage and financing activities made him one of the wealthiest people in the United States at the time. He bequested a former hotel property to a failing Presbyterian secondary school in Minneapolis, Minnesota that became Macalester College and was named in his honor. His Glengarry estate in the Torresdale neighborhood of Philadelphia was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Charles Macalester | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 17, 1798 |

| Died | December 9, 1873 |

| Burial place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, banker, real estate investor, philanthropist |

Early life and education

editMacalester was born in Philadelphia on February 17, 1798, to immigrant parents from Scotland. His father was a ship-master who sailed often to the East Indies and Europe.[1] Macalester was educated at Grey & Wylie's school and the University of Pennsylvania. While at university, he led a company of forty students to assist in the construction of a fort on the west bank of the Schuylkill River during the War of 1812.[2]

Career

editFrom 1821 to 1827, he worked as a merchant in Cincinnati, Ohio,[3] before returning to Philadelphia. On August 24, 1832, his father died and Macalester inherited a large estate. Macalester retired as a merchant in 1849,[4] but continued buying and selling securities and real estate.

He worked for the stock brokerage firm Gaw, Macalester & Co., was an agent for the American-British financier George Peabody, a director of the Fidelity Insurance, Trust & Safe Deposit Co.,[3] a director of the Girard National Bank[5] and a director of the Camden & Amboy Railroad Company. He made real estate investments, especially in Chicago,[3] and was one of the wealthiest people in the United States.[4]

In the 1830s, he was appointed as government director for the Second Bank of the United States[6] by Andrew Jackson and served in that capacity when the bank charter expired.[5] He was an advisor and friend to several U.S. Presidents including James Buchanan, Millard Fillmore, Ulysses S. Grant, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Pierce, James K. Polk and Martin Van Buren.[7] He was offered a cabinet post several times but never accepted.[8]

In 1850, Macalester purchased 84 acres of land in the Torresdale neighborhood of Philadelphia and built a grand country estate that he named Glengarry.[4]

Philanthropy

editIn the 1870s, Rev. Dr. Edward Duffield Neill asked Macalester for sponsorship for the failing Baldwin College in Minnesota.[9] J. Macalester bequested the Winslow House, a summer hotel in Minneapolis which overlooked Saint Anthonys Falls.[10] Neill agreed to rename the school Macalester College in honor of the gift and the college was chartered in 1874.[11] In 1885, the college sold the Winslow House property for $40,000[12] and moved to its present location, on Snelling Avenue at Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota.[13]

He was a trustee of the Presbyterian Hospital of Philadelphia, the Jefferson Medical College and the Peabody Southern Education Fund. He served as president of the St. Andrew's Society.[14]

Personal life

editHe was first married in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1824 to Eliza A. Lyttle and together they had two children. He was married again in 1841 to Susan Wallace.[2]

Death and legacy

editHe died at his Glengarry estate in the Torresdale neighborhood of Philadelphia on December 9, 1873.[1] He was interred in a mausoleum at Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, in Section 10, Lot 45.[15]

In his will, he bequeathed $5,000 for Presbyterian missions, $5,000 for the Presbyterian Board of Education, and $5,000 for the Fund for Disabled Ministers of the Presbyterian church. The name of Baldwin College was changed to Macalester College in honor of his donation of the Winslow Hotel which founded the school.[14] He also left other charitable bequests.[16][17]

The Charles Macalester Society at Macalester College was named in his honor and set up to recognize individuals whose lifetime donations to the school have exceeded $1 million.[7]

His Glengarry estate in the Torresdale neighborhood of Philadelphia was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[18]

References

editCitations

- ^ a b Hotchkin, S.F. (1893). The Bristol Pike. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co. pp. 228–230. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b Blanchard, Charles (1900). The Progressive Men of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Logansport, Indiana: A.W. Bowen & Co. pp. 874–879. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Funk 1910, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Walton, Meg Sharp. "Cultural Landscape Survey Glen Foerd on the Delaware" (PDF). www.static1.squarespace.com. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ a b Leach, Josiah Granville (1902). The History of the Girard National Bank of Philadelphia 1832-1902. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company. p. 83. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Kilde 2010, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b "Charles Macalester Society". www.macalester.edu. Macalester College. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Stern, Milton (2005). Harriet Lane, America's First Lady. lulu.com. ISBN 9781411626089. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Kiehl, David (1905). History of education in Minnesota. The Historical Society. p. 4. LCCN 18010428. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Funk 1910, p. 37.

- ^ "Macalester's History". www.macalester.edu. Macalester College. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Funk 1910, p. 82.

- ^ Kilde 2010, p. 62.

- ^ a b Funk 1910, p. 47.

- ^ "Charles Macalester, Jr". www.remembermyjourney.com. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Kilde 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Hall, Henry (1896). America's Successful Men of Affairs: An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography. New York: The New York Tribune. p. 538. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Glen Foerd on the Delaware". www.loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

Sources

- Funk, Henry Daniel (1910). A History of Macalester College - Its Origin, Struggle and Growth. Macalester College Board of Trustees.

- Kilde, Jeanne Halgren (2010). Nature and Revelation: A History of Macalester College. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5626-4.