Charles Frederick Beyer (an anglicised form of his original German name Carl Friedrich Beyer) (14 May 1813 – 2 June 1876) was a celebrated German-British locomotive designer and builder, and co-founder of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. He was the co-founder and head engineer of Beyer, Peacock and Company in Gorton, Manchester.[1] A philanthropist and deeply religious, he founded three parish churches (and associated schools) in Gorton, was a governor of The Manchester Grammar School, and remains the single biggest donor to what is today the University of Manchester.[2] He is buried in the graveyard of Llantysilio Church, Llantysilio, Llangollen, Denbighshire North Wales. Llantysilio Church is within the grounds of his former 700 acre Llantysilio Hall estate. His mansion house, built 1872–1874, is nearby.

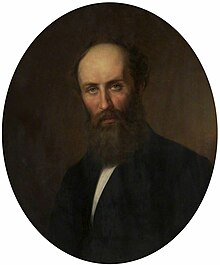

Charles Frederick Beyer (orig. Carl Friedrich Beyer) | |

|---|---|

by Carl Friedrich Schmid | |

| Born | 14 May 1813 |

| Died | 2 June 1876 (aged 63) Llantysilio, near Llangollen, Wales |

| Education | Dresden Polytechnic |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Institutions | Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Institution of Civil Engineers |

Early life and career

editGermany

editBeyer was from humble beginnings, the son of a weaver. Born in Plauen, Saxony, he was expected to follow in his father's footsteps and become a hand weaver's apprentice. He was taught to draw by a student architect convalescing in the district. His mother dreamt of him being an architect and she paid him to teach mathematics and drawing.[3] Some of his pinned-up drawings were noticed by an "eminent medical gentleman", a "Mr Von Sechendorf" (who was visiting another family member),[3] and a place was procured for him at Dresden Polytechnic, an institute of technical education (it was said that his parents were poor and had no money to send their son to college, but were afraid of giving offence to the civil servant). Beyer supplemented a meagre state scholarship by doing odd jobs (a philanthropic lady was in the habit of giving Sunday dinner to the student with the highest marks that week. Beyer relied on the meal, and consequently made sure that he out-performed everyone else).

Upon completing his studies at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, Beyer took a job in a machine works at Chemnitz, and he obtained a state grant from the Saxon Government to visit the United Kingdom to report on weaving machine technology. He visited Manchester, the world's first industrial city. It was the cotton mills that drove the local economy. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the world's first steam hauled purpose built passenger railway, had just opened and people were now able to travel faster than horses for the first time. He returned to Dresden to file his report on the latest developments in cotton mill technology, and was rewarded by the Saxon government.

England

editDespite two offers to manage Saxony cotton mills, Beyer was determined to return to Manchester. In 1834, aged 21 and speaking little English, he returned to Manchester, accompanied by his teacher, Professor Schubert, who introduced him to S. Behrens and Co, a well-known merchant in the city. While they could not help him, they obtained an interview for him with Sharp, Roberts & Co, (Atlas Works), where he impressed Thomas Sharp. However, Sharp risked alienating his workers by employing a German immigrant with a poor command of English; Sharp explained the situation to Beyer and offered him a sovereign to cover his travelling costs. Beyer refused the money exclaiming: "It is work I want", and insisting he was prepared to work for very little money. Impressed by Beyer's attitude, Sharp took the risk and employed him as a low-paid draughtsman, working under the guidance of head engineer Richard Roberts.

In 1852, when admitted to the Institution of Civil Engineers, his address was stated as 60, Cecil Street, Manchester. His proposer was Richard Roberts, and he was seconded by Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The 1861 census states that Beyer lived at 9, Hyde Road, Manchester age 47, engineer employing of 800 men birth Saxony, Eliza Seddon, 55, widow, born Wales, housekeeper, born Manchester, Catherine Ellis, 50, widow, cook, Mary Jones, 23, house servant, born Wales, Ann Hughes, 23, house servant, born Wales. His neighbour at 11, Hyde Road was Charles Sacré, 29, civil engineer,

In 1868, the UK Poll Book states that in the Parish of Llantysilio, he stated his address as Stanley Grove, Oxford Street, Manchester, (now the site of Manchester Royal Infirmary, teaching hospital). He voted for Sir Watkin Wynn

The 1871 census states that Beyer lived at 1, Stanley Grove, Oxford Street, (now Oxford Road), Manchester. He was 57 years old at the time and he stated that his occupation was "Mechanical engineer, employer of the firm Beyer, Peacock and Co., Locomotive builders, about 1,500 men and owner of about 700 acres of land in the parish of Llantysilio, (Llantysilio Hall), N. Wales". Suzannah Williams, 54, housekeeper born Gwyddelwyn, N. Wales (near Llantysilio), Elizabeth Hughes, 44, housemaid, born Chorlton on Medlock, Catherine Evans, 25, waitress, born Llangollen, Winifred Roberts, 22, kitchen maid, born Llanfor.

His neighbour at 5, Stanley Grove then 19 years old, and from Frankfurt, Germany: Arthur Schuster, destined to become the first Beyer Professor of Applied Mathematics. He was Professor of Physics (1888–1907) when Owens College became the Victoria University of Manchester (Est 1904). In the First World War Schuster was accused of spying when he had possession of a radio that could receive signals from Paris and Berlin (he sued his accusers and gave the money to charity).

Another neighbour, at 4, Stanley Grove, was Salomon L Behrens, aged 83, the founder of S. Behrens & Co., who 37 years previously, introduced Beyer to Richard Roberts in 1834 (see below).

Friedrich Engels also lived in the neighbourhood 1840–1870; 25 and 58 Dover Street and 6 Thorncliffe Grove (now Thorncliffe House, a University of Manchester hall of residence; (Karl Marx was a frequent visitor to Engels in Manchester). Engels wrote The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 following his study into the conditions faced by Victorian workers in the cotton mills of Manchester.[4] Beyer had just become the head engineer at Atlas Works at the time.[1]

Sharp, Roberts and Co

editThe company manufactured cotton mill machinery and had just started building locomotives for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Roberts was a prolific inventor despite being self-taught, with no university education or training. His genius was constrained by his inability to clearly state his ideas on paper; he said of his draughtsman:

- "There is a man who can tell every word I say, but cannot put my ideas upon paper; and here is another (Mr. Beyer) who scarcely knows English, but who can not only understand but also put into shape all that I mean."

Beyer's technical training in Dresden, coupled with his natural aptitude for drawing and design, made him a perfect partner for Roberts.

The latter's skills in designing cotton mill machinery did not translate into success in locomotive design, but he put his faith in Beyer and let him take over design and production of the company's new locomotives. Beyer designed the locomotives that made Sharp, Roberts & Co famous as locomotive builders. Roberts retired from the firm in 1843, and Beyer became chief engineer.

In 1842 Beyer designed a tender which became the standard for British railways. featuring outside frames. On 3 October 1846, one of his 0-6-0 "luggage" engines hauled a train of 101 wagons weighing 597 tons from Longsight in Manchester to Crewe, 29 miles at an average speed of 13.7 mph. This was a world record at the time. In 1847, a similar locomotive, ran 3,004 miles on the London and Birmingham railway with a coke consumption of only 0.214 lb per ton per mile.The next best locomotive burned 0.38 lb per mile, another record.[1] By 1849, Beyer had helped produce over 600 locomotives.

In 1844 the King of Saxony visited the Atlas; Beyer showed him the works, and soon the Saxony government was ordering locomotives from the company. Beyer's main design features were placing the boiler line at a higher level which made for smoother running. He was the first to give the boiler freedom to expand. The shape and appearance of British railway locomotives owed more to Beyer, than any other designer.[1]

On 5 November 1852 Beyer was naturalised in England.[5] The following year (1853), despite being at the height of his chosen profession, vice-President of the IMechE and a friend of George Stephenson, Robert Stephenson, Sir Daniel Gooch, John Ramsbottom and others,[3] he left the company. This move may have resulted after he was overlooked for a partnership (Mr C P Stewart was appointed a partner),[5] or possibly because of his unrequited love for one of the Sharp nieces; nonetheless he spent six months touring Europe and contemplating study at Oxford or Cambridge.[3]

Institution of Mechanical Engineers

editBeyer was a co-founder of this institution. Grace's Guide states:

- "At the opening of the present headquarters in Birdcage Walk in 1899 a commemorative pamphlet was issued to members stating that the meeting took place in a house in Cecil Street, Manchester at the house of a Charles Beyer, the manager of Sharp Brothers locomotive works. Although Beyer was very much involved in the formation of the IMechE, it is more likely that the meeting was no more than a conversation among friends."[6]

Alternatively, the idea was discussed informally at Bromsgrove at the house of James McConnell, after viewing locomotive trials at the Lickey Incline. Charles Beyer, Richard Peacock, George Selby, Archibald Slate and Edward Humphreys were present. Bromsgrove may be the more likely candidate for the initial discussion, not least because of McConnell was also a driving force in the early years.[7] A meeting took place at the Queens Hotel in Birmingham to consider the idea further on 7 October and a committee appointed with McDonnell at its head to see the idea to its inauguration.[8]

Whether the informal gathering with George Stephenson and friends at Beyer's house on Cecil Street, or the meeting at Bromsgrove, was the first point at which the idea was raised, by the autumn 1846 these discussions did lead to the formal founding at the Queen Hotel at Curzon Street, Birmingham on 27 January 1847. Beyer proposed Stephenson as president; Beyer was elected vice-president.[6]

Beyer was also a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and, from 24 January 1854, a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.[9] John Dalton, James Prescott Joule, William Fairbairn, Henry Roscoe and Joseph Whitworth were contemporary members.

Beyer, Peacock and Company

editRichard Peacock resigned from his position as chief engineer of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway's locomotive works in Gorton in 1854. Confident in his ability to secure orders to build locomotives, Beyer's resignation presented Peacock with a partnership opportunity. However, this was not a limited company and all partners were liable for debts should the business fail; in a mid-Victorian economic climate of boom and bust, it was a risky venture. Beyer could raise £9,524 (nearly £900,000 in 2015) and Peacock £5,500 but still required a loan from Charles Geach (founder of the Midland Bank, and first treasurer of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers). Unfortunately, Geach died in November 1854, the loan was recalled and the whole project nearly died. To the rescue came Thomas Brassey who persuaded Henry Robertson to provide a £4,000 loan in return for being the third (sleeping) partner.[1]

Beyer and the Great Western Railway

editRobertson's investment would be the start of a long friendship between Beyer and Robertson (Beyer became the godfather of Robertson's daughter Annie born in 1854). The civil engineer was responsible for the lines of the Northern division of the Great Western Railway (Brunel was the South) and a friend of Sir Daniel Gooch, its chief locomotive superintendent. He could therefore procure orders for the GWR. The first order was for ten Beyer, Peacock express 2-2-2 tender express engines of standard (rather than broad) gauge – the first standard gauge locomotives ordered by the GWR (Swindon were still building broad gauge engines). The locomotives were to be built to Gooch's own design which saved time in the drawing room. Joseph Armstrong was Gooch's successor as chief mechanical engineer at Swindon locomotive works and knew Beyer's engines. He was chief locomotive superintendent when Shrewsbury and Chester Railway ordered Beyer-designed Sharp, Stewart locomotives. Ten years later, when the GWR needed a new 0-6-0 goods engine, he allowed Beyer to design the locomotives himself. The GWR "Beyer Goods" locomotive proved to be an outstanding performer and some were still running 80 years later. Beyer's godson Sir Henry Beyer Robertson, born in 1864 would (many years after Beyer's death) become a director of the Great Western Railway, continuing the "family's" connection with the GWR.[1]

Gorton Foundry

editA 12-acre site was chosen in Gorton village, two miles from the centre of Manchester, on the opposite side of the Manchester Lincoln and Sheffield Railway line to Peacock's previous works. Beyer designed the works, planning them so well for possible expansion that, during its 112-year history, no buildings needed to be demolished to make way for new or extended buildings – in stark contrast to Beyer's previous Atlas works in central Manchester where land was expensive with no room to expand. Beyer also established a foundry, designed and manufactured the machine tools needed to build the locomotives, and stayed at Gorton Foundry and supervised the design and production of the locomotives. Peacock meanwhile dealt with the business side, often travelling the continent to secure orders.[1]

Beyer and elegant design

editCharles Beyer took great pride in the look of his locomotives, often spending hours with his pencil drawing a dainty curve and taking pride in the aesthetic appearance of his work. One particular 2-2-2 locomotive "D. Luiz" was exhibited at the 1862 International Exhibition. This locomotive was built for the South Eastern Railway of Portugal.[10] It was similar to the locomotives then being delivered to the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway. It was awarded a medal, noted for its beauty of form, and did much to promote the company.[1]

Beyer chose German-trained engineers rather than British because there were no engineering schools in UK at that time that were comparable to those in Germany. There were several German immigrants on the staff. The company became one of the most famous locomotive builders in the world noted for its precision engineering, quality of workmanship, beauty and longevity. It made all three partners very rich men.[1]

London's underground railway

editBeyer appointed and worked closely with Hermann Ludwig Lange (1837–92), in 1861. A native of his home town, Plauen, Saxony (now Germany), Lange trained as an engineer in Germany, became chief draughtsman in 1865, and chief engineer after Beyer's death. Lange was heavily involved in the development of the world's first successful condensing locomotives for the Metropolitan Railway. The Metropolitan initially ordered 18 tank locomotives, of which a key feature was condensing equipment which prevented most of the steam from escaping while trains were in tunnels, and have been described as "beautiful little engines, painted green and distinguished particularly by their enormous external cylinders."[11] The design proved so successful that eventually 120 were built to provide traction on the Metropolitan, the District Railway (in 1871) and all other 'cut and cover' underground lines.[11] This 4-4-0 tank engine can therefore be considered as the pioneer motive power on London's first underground railway;[12] ultimately, 148 were built between 1864 and 1886 for various railways, and most kept running until electrification in 1905. Metropolitan Railway No 23 which entered service in 1866 was not withdrawn until 1948 after 82 years.[1] It is now an exhibit in the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden.

Philanthropy

editAged 50, on 13 June 1863 Beyer wrote in his diary;

- Have Mercy Upon Me, O Lord, and grant that the Goods Thou hast entrusted to my keeping may bear fruit to thy Honour and Glory, through Jesus Christ.[1]

Beyer was a bachelor and had no children. A rich man, he began to spend his wealth on building schools and churches. Education was his main priority. He supported the Ragged School as well as church day and Sunday schools, scholarships for The Manchester Grammar School (where he was governor) and at university level with Owens College (effectively creating a pathway by which a child from a poor background – such as Beyer's – could graduate with a university degree in engineering, previously mainly restricted to those who could afford such an education).[13]

Church of England

editHe was also a major donor to the Church of England.[1] In 1865 Beyer provided most of the cost for the construction of St Mark's Parish Church, West Gorton, as well as bearing the full cost of building the associated day school[14] (in 1880 this church formed a football team which became Gorton AFC, then Ardwick AFC[15] and finally Manchester City Football Club).[14] In 1871 he bore the whole cost of rebuilding the old parish church of St Thomas in Gorton, subsequently renamed St James’ Parish Church.[1] He was an original member of Gorton Conservative Association, now St James Conservative Club, Gorton Lane.[14]

Less than two weeks before his death, Beyer added a codicil to his will to provide money to build a third parish church and its associated rectory and he specified that it should be called All Saints'.[13]

All Saints' was destroyed by fire in 1964 and subsequently demolished; a new church was built on the old site in 1975 and renamed Emmanuel Church. In 1968, St Mark's and All Saints' churches were united into one parish; St Mark's was demolished in 1974, leaving the two churches today represented by Emmanuel Church and All Saints' Primary School.

Beyer also did major improvements to Llantysilio parish church, and left money in his will to augment the stipend of the vicar.[13]

Beyer and the Owens Extension College Movement

editOwens College had been founded in 1851, funded from the will of a rich local textile merchant, John Owens. It was founded in response to the non-admission of non-conformists to Cambridge and Oxford but had several problems in the 1860s. First, it was not a university, but a college affiliated to the University of London. Students had to satisfy London examiners and London controlled the syllabus. Manchester wanted its own university, where northerners could study and receive degrees locally. Second, to become an independent university, the college had to expand. While the Quay Street premises (rented at a nominal amount) were becoming overcrowded, Owens had expressly stated that none of his money should go to the construction of buildings. His will made it difficult to raise public funds; only local people could attend, women were forbidden entry, and the lower age limit competed with grammar schools and would affect the quality of teaching.

Beyer suggested a public appeal to create a new college on a different site that would allow the Owens College to expand. The Owens Extension College Movement began in 1867 with appeals directed particularly at rich mill-owners and the textile trade. The wealthy and charismatic mill-owner, Thomas Ashton, a fine public speaker, was chosen to lead the campaign, with support from chemist and Owens College Professor Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe. Both Ashton and Roscoe had trained at Heidelberg University (Roscoe had been taught by Professor Robert Bunsen). Manchester wanted to follow the German university model, with an emphasis on research rather than the dogmatic teachings of ancient universities (e.g.: Oxford and Cambridge). Study tours were organised to mainly German Universities including Heidelberg and Berlin, and also to new polytechnics like the Dresden Academy, where Beyer had trained.

Beyer served on the Canvassing and Financial committee, and on the Buildings Committee, where he discussed proposals with architect Alfred Waterhouse. A site on Oxford Road in central Manchester was selected and work on the Owens Extension College started in 1870. Then by amalgamating the two colleges by Act of parliament (John Owens' will conditions were over-ruled; women could, in theory, be admitted, and the lower age limit was increased to 16), the new Owens College was born on 1 September 1871.

The new college building opened in 1873. The move to Oxford Road also allowed the Manchester Royal School of Medicine and Surgery to move to the site in 1874; amalgamating this with Owens College raised its profile in its quest to become an independent university. However, the college encountered a financial crisis in 1876. Many benefactors had died and income had fallen dramatically. When Beyer died in 1876, his will (written in 1872) bequeathed £114,000 (equivalent to £10 million in 2013) to the college and secured its future. Beyer had been the largest single donor when alive and the largest single benefactor in the history of the University of Manchester.[2] The funds were eventually appropriated to build the Beyer Building in 1888, and fund professorships in Engineering and Mathematics. The college was now destined to become the Victoria University of Manchester, a university with a strong German heritage, connections with Heidelberg and following its methods of teaching through experiment. It would become one of the world's leading science research Universities.[2][3][13][16][17]

Today's University of Manchester was formed by the amalgamation of the Victoria University of Manchester and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) in 2004.[18] UMIST's history dated from 1824 when John Dalton (father of atomic theory) and others formed the Manchester Mechanics' Institute. Beyer had been a member since 1847 and a life member from 1850; while focused mainly on Owens College, he had therefore been a supporter of both institutions.[16]

Beyer and Owens College department of engineering

editBeyer's first contact with Owens college was in 1860 when he was introduction to Professor Greenwood.[3] In parallel with the campaign to turn Owens College into a university, Beyer was keen to establish a suitable engineering school such as those in Germany; he had attended such an institution, and knew there was no similar facility to train new engineers in Britain. Moreover, he wanted to establish an engineering department within the college rather than as a separate entity outside the university, as in Germany.

When a chair was advertised at a salary of £250 per annum the selection committee was unsatisfied with the quality of the applicants. It was recorded that Beyer decided to double the salary: "Mr Beyer…. most generously offered to supplement the salary by the sum of £250 for 5yrs…." When the post was re-advertised, they were able to appoint Professor Osborne Reynolds (not to be confused with Professor John Henry Reynolds of the Manchester Technical School) on 26 March 1868. The first professor of engineering in the north of England, Reynolds did much to engage local engineering firms in applied science with mutual benefit, giving the college a worldwide reputation before retiring in 1905.[16][19]

Charles Beyer was also a donor to the Sir Henry Roscoe's chemistry department.[19]

Personal life

editBeyer became a British Subject in 1852 and was based in Manchester ever since emigrating there in 1834 at the age of 21.[1] Of his personal life, Ernest F. Lang wrote:[20]

- "Mr Beyer remained all his life a bachelor. Whilst with his old firm he had fallen in love with Miss Sharp, a daughter of one of the partners, but she, although strongly attracted towards Mr Beyer, gave preference to another suitor. This was his first and only romance. Gorton Foundry was destined to become and remain his chief preoccupation in life."[20]

He shared, however, a mutual homosexual affection with Swedish engineer Gustav Theodor Stieler.[21]

The Last Will and Testament of Charles Frederick Beyer

edit(Extracts)

" I bequeath to my Nephew Franz Hermann Beyer, son of my late Brother Ernst Beyer the Legacy or sum of £15,000 " (£1,500,000)*

" To my Nephew Carl Frederick Beyer another son of my said late Brother Ernst the legacy or sum of £5,000." (£500,000)*

" I bequeath to my Sister Johanna Christiana Weber Widow the Legacy or sum of £10,000 (£1,000,000)* for her own use and benefit ... bequeath to my housekeeper Susan Williams the legacy of £500 (£50,000)*in addition to any wages owing to her and also a suit of mourning"

" And to my gardener Edward Hart the legacy of £500 (£50,000)* in addition to any wages owing to him and also a suit of mourning"

" To each of my other domestic servants who shall have been in my service for two years prior to and shall be in my service at the time of my decease and to Rees Jones of Llantysilio in the County of Denbigh if he shall be in my employ at the time of my decease the legacy of £100 a piece (£10,000)* in addition to any wages owing to them and also a suit of mourning."

" I bequeath to each of the following persons, assistants at the Gorton Foundry. that is to say Thomas Molyneaux the legacy of £1,000 (£100,000) and to each of them Hermon Jaeger and Charles Holt the legacy or sum of £500 (£50,000)* a piece."

" I bequeath the sum of £3,000 (£300.000)* to my said Trustees upon trust either to pay over the same to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England or at their discretion to lay out and invest the same in their own names in or upon such securities or investments as they are by law authorised to lay out and invest the same and to stand possessed of the securities or investments for the time being in or upon which the same shall be laid out or invested with power from time to time to alter vary or transpose such securities or investments upon trust to pay the interest dividends or annual income to arise therefore unto the Vicar or incumbent for the time being of the Parish Church of Llantysilio in the County of Denbigh in augmentation of income of such a vicar or incumbent for ever."'

" I devise all that my messuage or mansion house known as Llantysilio Hall in the County of Denbigh with the lands.... .. to the use of my Godson Henry Beyer Robertson"" To the use of my god daughter Annie Robertson, daughter of the said Henry Robertson for her life without impeachment of waste for her sole and separate use independently of any husband with whom she shall intermarry and of his debts control and engagements and from and after the decease of the said Annie Robertson"

" Upon trust for and i bequeath the same accordingly to and for the purposes and benefit of Owens College in Manchester to be applied in such manner as the governing body for the time being shall think expedient in or towards the foundation and endowment of professorships in science, one at least shall be a professorship in Engineering in the said college." (£10,000,000)*

" pay and apply the ultimate residue of the same moneys to and for the purposes and benefits of Owens college in Manchester aforesaid in or towards the foundation or endowment of professorships therein as they my said trustees and the governing body for the time being of the said college shall think expedient."

" In witness thereof, I the said testator Charles Frederick Beyer have to this, my last will and testament contained on 10 sheets of paper subscribed by my hand this 19th day March 1872."

C F Beyer.

Codicil

Dated 13 May (the eve of his 63rd birthday, and less than three weeks before he died).

" Whereas since the date of my said Will, I have built the mansion house in which i am now residing at Llantysilio and made many additions to and improvements in and upon my estate and have furnished and fitted up my said mansion house."

" Now it is my will that the person or persons for the time being entitled to my said estate shall have and take the full benefit and enjoyment of my said mansion house and all additions and improvements to my estate in the County of Denbigh and the use of all the household furniture, effects of domestic use and all the plated articles, pictures and works of ornament which shall be in my said mansion house at the time of my death as heir looms according to the limitations of my said will relating to my said estate."

" And I bequeath the same to the trustees named in my said will accordingly to be held by them upon for and subject to the uses, trusts and provisions expressed and declared in and by my said Will."

" And whereas i have conveyed to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England a certain piece of land at Gorton as and for the site of a church to be called All Saints Church and a parsonage house to the said church and it is my intention to build such church and house upon the said land."

"Now in case I shall not carry such my intention into effect in my lifetime I bequeath to my trustees named in my said Will the sum of £10,000 (£1,000,000)* in case I shall not have commenced to build and in case i shall commenced but not completed building such a sum as with the money expended in my lifetime on the said object shall make up the sum of £10,000 to be by them applied in building or competing the erection of the said church and house in such manner as my said trustees shall think fit and if the whole of the said sum of £10,000 (£1,000,000)* shall not be required for the purpose of building the said church and house then to pay the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England the balance of the said sum £10,000 to be applied in or towards providing an endowment for the said church and I direct that the said legacy shall be paid out of my personal estate as can legally applied to charitable purposes in the same manner and the like priority of payment as is directed by my said Will with respect to the charitable legacies and bequests thereby given or bequeathed in all other respects."

" I confirm my said Will in witness which I have hereinto set my hand, this 13th day May 1876."

C F Beyer

(Courtesy Denbighshire Archives)

*denotes approximate value today measured by wage inflation.

Llantysilio Hall

editBeyer purchased the 700-acre Llantysilio Hall estate, at the head of the Vale of Llangollen, Denbighshire,North Wales, in 1867, and built a new 25-bedroom mansion house on the property (1872–1874), then demolishing the old house of the Thomas Jones family. The architect was Samuel Pountney Smith of Shrewsbury (architect of Palé Hall, station buildings on Henry Robertson's railways and the nearby Chainbridge hotel).

The hall, situated near the Horseshoe falls on the River Dee at the head of the Llangollen Canal, was lavishly decorated.[22] For example, the larger, south-facing, drawing room has a Carrara marble chimneypiece with giallo antico columns and three cameos in the frieze, of

- Queen Victoria,

- Elizabeth Dean Robertson, Henry Robertson's wife, and

- Helena Faucit, celebrated Shakespearean actress (Beyer's nearest neighbour, at Bryntysilio Hall, wife of Sir Theodore Martin, author of the official biography of Prince Albert, Life of the Prince Consort).

The smaller drawing room, with interconnecting door has a similar chimneypiece depicting

- Kaiser Wilhelm, first German emperor,

- Otto von Bismarck, chancellor of German empire, and

- Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, victorious general of Franco-Prussion war, which led to the formation of the German Empire.

These pieces were probably made c. 1874, some three years after the foundation of the German Empire.

Charles Beyer died at Llantysilio Hall on 2 June 1876.[23] He was buried at Llantysilio church, in the grounds of his Llantysilio Hall estate.

References and sources

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hills, R. L. and Patrick, D. (1982). Beyer, Peacock: Locomotive Builders to the World. Glossop: Transport Publishing Co. ISBN 0-903839-41-5.

- ^ a b c "Bravo Beyer! Celebrating historic benefactor's 200th birthday (14 May 2013)". University of Manchester. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Charles Beyer: Obituary (1877)". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Coates, Su (2013). "Manchester's German Gentlemen;Immigrant Institutions in a provincial City 1840–1920" (PDF). University of Manchester. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b Hills, Richard L. (1967). "Some Contributions to Locomotive Development by Beyer, Peacock & Co.." Transactions of the Newcomen Society 1967; 40(1), 75–123. DOI: 10.1179/tns.1967.006. See also online extract

- ^ a b "Institution of Mechanical Engineers". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Pullin 1997, p. 2

- ^ Watson 1988, pp. 33–34

- ^ "Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester". 20 April 1858. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Portuguese Locomotive Types, The Restoration & Archiving Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ a b Wolmar, Christian (2004). The Subterranean Railway. London: Atlantic Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-1843540236.

- ^ Bruce, J Greame (1971). Steam to Silver;. London: London Transport. ISBN 978-0853290124.

- ^ a b c d Last Will and Testament of Charles Frederick Beyer; Denbighshire Archives

- ^ a b c "Orange and Blue – St Mark's (West Gorton), Rev Arthur Connell and Manchester City Football Club". Manchester Orange. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ James, Gary (2012). Manchester – The City Years. James Ward. ISBN 978-0-9558127-7-4. p48

- ^ a b c Portrait of The University of Manchester (2005). Third Millennium publishing.

- ^ Charlton, H.B. (1951). Portrait of a University 1851–1951. manchester: Manchester University Press.

- ^ "Our History". University of Manchester. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ a b Thompson, Joseph (1888). "Reviewed Work: The Owens College, Its Foundation and Growth, in Connection with the Victoria University, Manchester". The English Historical Review. 3 (12). Oxford University Press: 811. JSTOR 546976.

- ^ a b Lang, Ernest F (1927). "The Early History of our Firm" (PDF). Beyer-Peacock Quarterly Review. 1 (2): 13–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007.

- ^ Dawson, Anthony (5 June 2023). "Hidden Stories of Engineering: The queer German immigrant who became one of Britain's leading engineers". Railway Museum. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Llantysilio Hall, Llantysilio". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ England and Wales, FreeBMD Death Index, 1837–1915

Sources

edit- Marshall, John (2003). Biographical dictionary of Railway Engineers. Oxford: Railway & Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-22-3.

- Pullin, John (1997). Progress through Mechanical Engineering. Quiller Press. ISBN 978-1-899163-28-1.

- Cragg, Roger (1997). Civil Engineering Heritage: Wales and West Central England: Wales and West Central England, 2nd Edition. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2576-9.

- Watson, Garth (1988). The civils: the story of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Thomas Telford Limited. ISBN 978-0727703927.