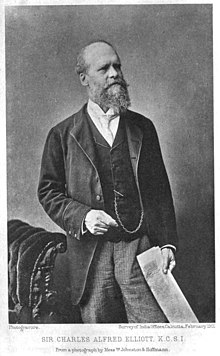

Sir Charles Alfred Elliott KCSI (8 December 1835 – 28 May 1911) was a Lieutenant Governor of Bengal.

Life

editHe was born on 8 December 1835 at Brighton, was son of Henry Venn Elliott, vicar of St. Mary's, Brighton, by his wife Julia, daughter of John Marshall of Hallsteads, Ulleswater, who was elected MP for Leeds with Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1832. After some education at Brighton College, Charles was sent to Harrow, and in 1854 won a scholarship at Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1856 the civil service of India was thrown open to public competition. Elliott, abandoning his Cambridge career, was appointed by the directors, under the provisions of the Government of India Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict c 95), one of fifteen members of the civil service of the East India Company (Despatch, 1 October 1856). He was learning his work unattached to any district, when the mutiny broke out at Meerut, and he was then posted on 12 June 1857 as assistant magistrate to Mirzapur in the Benares division of the North Western Provinces. That large district of 5238 square miles was the scene of fierce conflicts with the rebels. Elliott led several small expeditions from headquarters to quell disturbances, was favourably mentioned in despatches, and received the mutiny medal.[1]

In the following year he became an assistant-commissioner in Oudh, where he served in Unao, Cawnpore, and other districts until 1863. In Unao he gave early proof of his industry by collecting information about its history, its folklore, and its families. He published in 1862 at Allahabad for private circulation Chronicles of Oonao, believing "that a knowledge of the popular traditions and ballads gives to its possessor both influence over the people and the key to their hearts." When this treatise was printed he was serving in the North Western Provinces, and in the following year (Sir) Richard Temple, wishing to strengthen the administrative staff of the Central Provinces, then under his control, secured Elliott's transfer, entrusting to him the settlement of the Narmadapuram district. This task, which greatly raised his reputation, was completed in 1865, being regarded as a most successful operation, which has stood the test of time. Taking furlough, Elliott returned to duty in the North Western Provinces, and was entrusted with the settlement of the Farukhabad district. He had assessed the whole district except the Tahwatahsil, when in 1870 he was chosen by Sir William Muir to be secretary to government. The final report, drawn up by H. F. Evans, 22 July 1875, included the rent rate reports written by Elliott "in that elaborate and careful manner which," according to Sir Charles Crosthwaite, "has become the model for similar reports." The cost of the settlement exceeded five lakhs, and although the rates charged were moderate, government received additional revenue of 22 per cent, on the expenditure, while the records were a permanent gain to the people. Settlement work, to which Elliott had thus devoted his best years, was in those days the most important and most coveted employment in the civil service, and it gave Elliott a thorough acquaintance with the needs of the people and the administrative machinery. From 1872 to 1875 he held the post of secretary to the government of the North Western Provinces, being concerned chiefly with settlement and revenue questions, with measures for suppressing infanticide in certain Rajput communities, and municipal administrations. Knowing every detail, he was inclined to interfere too much with subordinate authorities. After Sir John Strachey had succeeded to the government of Sir William Muir, he went to Meerut as commissioner. Thence he was summoned by Lord Lytton to visit Madras, and subsequently to apply to Mysore the famine policy of the paramount power. As Lord Lytton wrote in November 1878, when reviewing his famine report on Mysore, "he organised and directed relief operations with a patience and good sense which overcame all difficulties, and with the fullest tenderness to the people in dire calamity." Elliott did not minimise the human suffering and the administrative shortcomings which he witnessed, and his experience and report indicated him as the best secretary possible to the royal commission on Indian famines (16 May 1878). Other commissions in 1898 and 1901 have built on the foundation laid by the famous report of 7 July 1878, but it will always remain a landmark in Indian history; for from that date the British government determined to fight with all its resources recurring and inevitable droughts, which had previously entailed heavy loss of life. For the planning of requisite organisation no knowledge detail was superfluous, and no better secretary could have been found for guiding and assisting the commissioners.[1]

This work completed, Elliott became for a few months census commissioner for the first decennial census for 1881 which followed the imperfect enumeration of 1872. In March 1881 he became chief commissioner of Assam, and in Feb. 1886 was entrusted with the unpopular task of presiding over a committee appointed to inquire into public expenditure throughout India, and report on economies. A falling exchange and a heavy bill for war operations compelled Lord Dufferin to apply the shears to provincial expenditure, and while the committee inevitably withdrew funds needed by the local governments, it was generally recognised that immense pains were taken by Elliott and his colleagues. Elliott, who had been made C.S.I. in 1878, was promoted K.C.S.I. in 1887, and from 6 January 1888 to 17 December 1890 he was a member successively of Lord Dufferin's and then of Lord Lansdowne's executive councils. On the retirement of Sir Steuart Bayley, Elliott, although he had never served in Bengal, became lieutenant-governor of that province, holding the post, save for a short leave in 1893, until 18 Dec. 1895. The greatest service which Elliott rendered to Bengal was the prosecution of the survey and the compilation of the record of rights in Bihar, carried out in spite of much opposition from the zemindars, opposition that received some support from Lord Randolph Churchill. Sir Antony MacDonnell's views as to the maintenance of the record were not in harmony with those of Elliott, but Lord Lansdowne intervened to reduce the controversy to its proper dimensions. Public opinion has finally endorsed the opinion expressed by Mr. C. E. Buckland in Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors (1901), that "there was not another man in India who could have done the settlement work he did in Bihar and Bengal, so much of it and so well." In his zeal for the public service Elliott courageously faced unpopularity. Economy as well as efficiency were his principles of government. Towards the native press he took a firm attitude, prosecuting the editor and manager of the Bangobasi for sedition in the teeth of hostile criticism. He was inclined to establish a press bureau, but Lord Lansdowne's government did not sanction his proposals. With the distressed Eurasian community he showed generous sympathy, and, always on the watch for the well-being of the masses he pushed on sanitary and medical measures, being largely instrumental in the widespread distribution of quinine as a remedy against fever. In foreign affairs he was impatient of Chinese delays in the delimitation of the frontiers of Tibet and Sikkim, and urged Lord Elgin to occupy the Chambi Valley (19 November 1895), and even to annex it.[1]

After a strenuous service of forty years he retired in December 1895, and was soon afterwards co-opted a member of the London School Board as a member of the moderate party, being elected for the Tower Hamlets division in 1897 and 1900. In 1904 he was co-opted a member of the education committee of the London County Council, serving till 1906. From 1897 to 1904 he was chairman of the finance committee of the school board, and his annual estimates were remarkable for their exceptional agreement with the actual expenditure. A strong churchman, he took active part in the work of missionary and charitable societies; he was a member of the House of Laymen as well as of the Representative Church Council. He was also chairman of Toynbee Hall.

He died at Wimbledon on 28 May 1911. He married twice: firstly on 20 June 1866 Louisa Jane (d. 1877), daughter of G. W. Dumbbell of Belmont, Isle of Man, by whom he had three sons and one daughter; and secondly on 22 September 1887 Alice Louisa, daughter of Thomas Gaussen of Hauteville, Guernsey, and widow of T. J. Murray of the I.C.S., by whom he had one son, Claude, who was fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. His eldest son by his first marriage, Henry Venn Elliott, was vicar of St. Mark's, Brighton. In his possession was a portrait of his father by Hugh Riviere. As a memorial to Elliott it was proposed to add a wing to St. Mary's Hall, Brighton, a church school in which he was especially interested.[1]

Elliott's contributions to Indian literature were mainly official. They included, besides the Chronicles of Oonao mentioned above, Report on the Narmadapuram Settlement (1866); Report on the Mysore Famine (1878); Report on the Famine Commission (1879); and Report on the Finance Commission (1887).[1]

Notes

editReferences

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee-Warner, William (1912). "Elliott, Charles Alfred". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Washbrook, David. "Elliott, Sir Charles Alfred (1835–1911)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33004. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)