In ancient Egyptian society chariotry stood as an independent unit in the King’s military force. Chariots are thought to have been first used as a weapon in Egypt by the Hyksos[1] in the 16th century BC. The Egyptians then developed their own chariot design.

Design

editArchaeologist Joost Crouwel writes that "chariots were not sudden inventions, but developed out of earlier vehicles that were mounted on disk or cross-bar wheels. This development can best be traced in the Near East, where spoke-wheeled and horse-drawn ‘true’ chariots are first attested in the earlier part of the second millennium BC...".[2] The early usage of chariots was mainly for transportation purposes. With technological improvements to their structure (such as a "cross-bar" form of wheel construction to reduce the vehicle's weight), the use of chariots for military purposes began. The Egyptians invented the yoke saddle for their chariot horses around 1500 BC. Chariots were effective for their high speed, mobility and strength which could not be matched by infantry at the time. They quickly became a powerful new weapon across the ancient Near East. The best-preserved examples of Egyptian chariots are the six specimens from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Chariots in warfare

editChariots were very expensive, heavy and prone to breakdowns, yet in contrast with early cavalry, chariots offered a more stable platform for archers.[citation needed] Chariots were also effective for archery because of the relatively long bows used, and even after the invention of the composite bow the length of the bow was not significantly reduced. Such a bow was difficult to handle while on horseback. A chariot could also carry more ammunition than a single rider. The chariot had a driver and one man with a bow.

However, the chariot also had several disadvantages, notably its size and its dependence on the right terrain. Their use has been compared to that of tanks in modern day warfare but this is disputed[3][4] by scholars who point out that chariots were vulnerable, fragile and required a level terrain while tanks are heavily armored all-terrain vehicles. Chariots were thus not suitable for use in the way modern tanks have been used as a physical shock force.[5][6]

Chariots would eventually form an elite force in the ancient Egyptian military. Infield action, chariots usually delivered the first strike and were closely followed by infantry advancing to exploit the resulting breakthrough, somewhat similar to how infantry might operate behind a group of armed vehicles in modern warfare. These tactics would work best against lines of less-disciplined light infantry militia. Chariots, much faster than foot-soldiers, pursued and dispersed broken enemies to seal the victory. Egyptian light chariots contained one driver and one warrior; both might be armed with bow and spear.

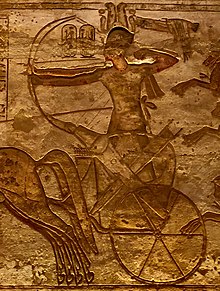

In ancient Egypt, members of the chariot corps formed their own aristocratic class known as the maryannu (young heroes).[citation needed] The heroic symbolism can be seen in contemporary paintings in which the King is shown riding with the elites, shooting arrows at the enemies. This image became typical of royal power iconography in the New Kingdom.[citation needed] As chariots become increasingly integrated into military training especially during the regime of Amenhotep II, the chariot warrior was identified as seneny and was paired with the called keijen or kedjen, who also act as his defender.[7] The seneny was trained to use the bow with accuracy even when the horse is at full gallop, a feat that Amenhotep II could reportedly do.[8]

The best known and preserved textual evidence about Egyptian chariots in action was from the Battle of Kadesh during the reign of Ramses II, which was probably the largest single chariot battle in history.[9] Kamose (1555–1550) has the distinction of being the first Egyptian ruler to use the chariot and cavalry units in battle, giving him victory. Accounts reveal that the Hyksos, who were lording over the northern territories in his reign, were startled when Egyptian chariots started to roll in the battlefield at Nefrusy, north of Cusae (near modern Asyut).[10] The chariots were improved versions of what they used to terrorize the enemy.[11][10]

References

edit- ^ Hyskos introduced chariots to ancient Egypt Archived 2010-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joost Crouwel (2013). "Studying the Six Chariots from the Tomb of Tutankhamun - An Update". In Veldmeijer, Andre J.; Ikram, Salima (eds.). Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference (Cairo 2012). Sidestone Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-9088902093.

- ^ Lloyd, Alan B. (2010). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley Blackwell. p. 438. ISBN 978-1-4051-5598-4.

- ^ Drews, Robert (1995). The end of the Bronze Age: changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. (new ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-691-02591-9.

- ^ Littauer, M.A.; J. H. Crouwel (1979). Wheeled vehicles and ridden animals in the ancient Near East. Brill. p. 98. ISBN 978-90-04-05953-5.

- ^ Gaebel, Robert E. Cavalry operations in the ancient Greek world. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8061-3444-4.

- ^ Morkot, Robert (2003). The A to Z of Ancient Egyptian Warfare. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780810876255.

- ^ Elliott, Paul (2017). Warfare in New Kingdom Egypt. Stroud, UK: Fonthill Media.

- ^ Dr. Aaron Ralby (2013). "Battle of Kadesh, c. 1274 BCE: Clash of Empires". Atlas of Military History. Parragon. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-4723-0963-1.

- ^ a b Bunson, Margaret (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. pp. 82. ISBN 978-0816045631.

- ^ Amstutz, L.J. (2015). Ancient Egypt. Minneapolis: ABDO Publishing. p. 86. ISBN 9781624035371.