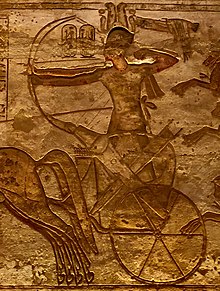

The first evidence of humans using vehicle in warfare are Sumerian depictions of four-wheeled wagons pulled by semi-domesticated onagers. These war wagons were slow and cumbersome, but provided a protected elevated platform for javelineers and slingers. Chariots with spoke-wheels pulled by horses were lightweight and fast which made it feasible to outrun light infantry and wagons. Although horses have been ridden as from at least the 4th millennium BC they were most likely largely relegated to transporting warriors, who fought on foot. Until the invention and widespread adoption of the saddle chariots remained the primary form of cavalry, as they offered a controllable and reliable platform from which fighters could rapidly manoeuvre around the battlefield and engage with projectile and melee weapons, dismount and fight on foot or climb on to make a swift retreat.[1][2]

Chariots on the battlefield

editChariots typically carried up to three armed warriors pulled by 2-4 horses. Usually there would be at least one driver responsible for holding the reins and the others engaged in fighting and commandeering. The speed of charioteers allowed them to effectively engage in hit-and-run tactics, skirmishing from afar with bows, javelins and slings before wheeling away from danger. In need or by sturdier design chariots could also effectively engage in melee. The charge of horses could easily break and trample loose infantry formations, while the riders could strike from their elevated platforms with spears, swords, axe and mace and protect themselves with shields and armour.[3][page needed] In antiquity heavy chariots with four mounted warriors with four barded horses would be developed. This chariot was a heavy construction and would sometimes be equipped with scythes on wheels.[4] The momentum of this heavy chariot was sufficient to break through enemy formations acting as heavy shock-troops. However engaging in melee was likely very dangerous as manoeuvring through densely packed infantry formations was unfeasible and any serious damage to the wheels or the horses could quickly render the charioteers stranded.[1][page needed][3][page needed] Chariots were most suited to flat and even terrain, but some chariots could be dismantled and carried across unfavourable terrain to be later assembled at need.[1]

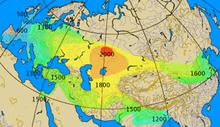

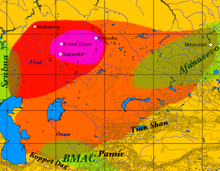

The bronze age was the heyday of the chariot. It was one of the main technological advances that allowed for the Indo-european migration throughout Eurasia[page needed] and the chariot remained a key status symbol and weapon of war of Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Hittites and Mycenaeans until the bronze age collapse.[1] After the victory of Alexander the Great against the Achaemenid empire, that still fielded armies with large chariot contingents, and the developments in horse riding, chariots fell out of favour throughout the Mediterranean.[3][page needed] While in India the adoption of the war elephant largely supplanted the use of chariots in battles.[5][page needed] The Celtic chariots called essedum were some of the last chariots used in warfare.[6][page needed] They had a light and agile structure. A heavily armoured warrior stood on a small platform with two independent-running spoked wheels. His driver sat on a thick rope net connecting the platform to the horses. It could quickly carry the nobleman into battle and evacuate him in case of danger, essentially acting as a mobile troop transport.[7] It was used in Europe until 100 BC and in Britain and Ireland until the year 200 AD.[3][page needed]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Anthony, David W. (2010). The horse, the wheel and language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton, N.J. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14818-2.

- ^ Bronze Age War Chariots By Nic Fields, Brian Delf

- ^ a b c d Cotterell, Arthur (2005). Chariot: from chariot to tank, the astounding rise and fall of the world's first war machine. Woodstock: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-667-5.

- ^ Rivet, A. L. F. (1979). "A note on scythed chariots". Antiquity. 53 (208): 130–132. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00042344. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Singh, Sarva Daman (1997). Ancient Indian warfare: with special reference to the vedic period (Repr. d. Ausg. Leiden : Brill ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0486-9.

- ^ Polybe; Waterfield, Robin Anthony Herschel; McGing, Brian C. (2010). The histories. Oxford world's classics. Oxford New York: Oxford university press. ISBN 978-0-19-953470-8.

- ^ Caesar], Caesar [Gaius Julius (1900-01-01), "De Bello Gallico", Oxford Classical Texts: C. Ivli Caesaris Commentariorvm, Vol. 1: Libri VII de Bello Gallico, Oxford University Press, pp. 1–1, retrieved 2023-10-24