This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

The chandelle is an aircraft control maneuver where the pilot combines a 180° turn with a climb.[1][2]

It is now required for attaining a commercial flight certificate in many countries. The Federal Aviation Administration in the United States requires such training.

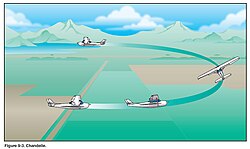

The chandelle (which is the French word for candle) is a precision aircraft control maneuver, and not strictly speaking an aerobatic, dogfighting, or aerial combat maneuver, however it was used with success by Japanese Zero pilots of the Tainan Air Group in 1942 over New Guinea. It is rather a maneuver designed to show the pilot's proficiency in controlling the aircraft while performing a minimum radius climbing turn at a constant rate of turn (expressed usually in degrees per second) through a 180° change of heading, arriving at the new reciprocal heading at an airspeed in the "slow-flight" regime, very near the aerodynamic stall. The aircraft can be flown in "slow-flight" after establishing the new heading, or normal cruise flight may be resumed, depending upon the purposes of the exercise or examination. See the diagram for a visual depiction of how the maneuver must be flown for the purpose of certification.

The pilot enters a chandelle at a predetermined airspeed in the normal cruising range for the aircraft. To begin the maneuver the pilot first rolls the aircraft in the desired direction with the controls (the ailerons), and quickly but smoothly establishes a medium-banked turn. In most small aircraft (cruising speeds of 100–175 KIAS) this bank will be about 30° to 40°. This will begin a turn of the aircraft in the direction of bank. Simultaneously, full power is applied and a smooth pitch up is started with the controls (the elevators on the empennage). The angle of bank stays constant during the first 90° of the change of heading, while the pitch angle increases steadily. At the 90° point in the change of heading, the aircraft has the maximum pitch angle (which should be close to the critical angle of attack at the level stall speed of the aircraft). During the second 90° of the change of heading, the pitch angle is held constant, while the bank angle is smoothly decreased to reach 0° of bank, the end of the turn and return to straight-and-level flight at exactly the reciprocal heading (180° away from the heading at the start of the maneuver), and with the airspeed close to the stall speed. The aircraft should not lose altitude during the last part of the maneuver, nor during the recovery, when engine power may be used to re-establish normal cruising speed on the new heading. The decreasing bank angle together with the decreasing airspeed during the second half of the chandelle will maintain a constant turn rate. The turn needs to be kept coordinated by applying the correct amount of rudder throughout the maneuver.

From a practical point of view, the chandelle may be used to turn an aircraft within a minimal turn radius. As such it is a useful maneuver for pilots of small aircraft who find themselves in a blind valley or canyon. It was also, therefore, a useful maneuver to early fighter pilots in their low-powered aircraft to quickly turn toward a pursuing attacker (which would tend to make a tracking gunshot more difficult because of the turn and climb involved) while climbing but not stalling the aircraft, or to position themselves quickly to make an attack on a turning enemy or an enemy flying on another heading.

French aviators during World War I described it as monter en chandelle, or "to climb vertically". However, it has since come to have a rather more strict definition for pilot flight testing purposes. In early fighter combat, a pilot would aim to achieve the maximum practical speed at full throttle, then roll the aircraft to the required angle of bank for the change of heading that was required in the combat situation. As the turn began, the nose is increasingly pitched up, as required for the amount or change of heading desired. As described above, the turn progresses with the desired pitch angle and requisite rudder to control yaw, airspeed decreases, and then the wings are leveled so as to roll out straight and level on the new desired heading, all the while avoiding an aerodynamic stall. At this point, if the pilot has any more power, it may be added to regain airspeed, or the nose of the aircraft can be allowed to drop somewhat to achieve the same effect (dropping the nose of the aircraft is not permitted for the purposes of the maneuver in commercial flight testing). In aerial combat, the chandelle maneuver was used both aggressively to position the aircraft for attack, and defensively to evade an enemy.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Crane, Dale: Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition, page 102. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ISBN 1-56027-287-2

- ^ "Chandelles In 60 Minutes"[permanent dead link] Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. Retrieved 2016-02-11.