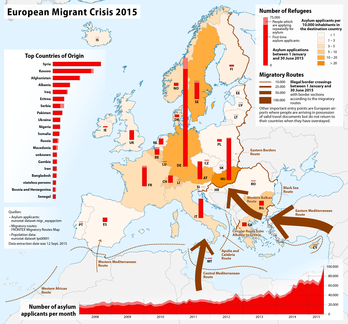

The 2015 European migrant crisis was a period of significantly increased movement of refugees and migrants into Europe, namely from the Middle East. An estimated 1.3 million people came to the continent to request asylum,[2] the most in a single year since World War II.[3] They were mostly Syrians,[4] but also included a significant number of people from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Eritrea,[5] and the Balkans.[6] The increase in asylum seekers has been attributed to factors such as the escalation of various wars in the Middle East and ISIL's territorial and military dominance in the region due to the Arab Winter, as well as Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt ceasing to accept Syrian asylum seekers.[7]

From top, left to right: Map of crisis,[a] Operation Triton, Refugees at Skala Sykamias Lesvos, Protesters at "Volem acollir" ("We want to welcome"), Protesters after New Year's Eve sexual assaults in Germany | |

| Date | 2014–2016 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

The EU attempted to enact some measures to address the problem,[8] including distributing refugees among member countries, tackling root causes of emigration in the home countries of migrants, and simplifying deportation processes.[9] However, due to a lack of political coordination at the European level, the distribution of countries was unequal, with some countries taking in many more refugees than others.

The initial responses of national governments varied greatly.[9] Many European Union (EU) governments reacted by closing their borders, and most countries refused to take in the arriving refugees. Germany would ultimately accept most of the refugees after the government decided to temporarily suspend its enforcement of the Dublin Regulation. Germany would receive over 440,000 asylum applications (0.5% of the population). Other countries that took in a significant number of refugees include Hungary (174,000; 1.8%), Sweden (156,000; 1.6%) and Austria (88,000; 1.0%).

The crisis had significant political consequences in Europe. The influx of migrants caused significant demographic and cultural changes in these countries. As a consequence, the public showed anxiety towards the sudden influx of immigrants, often expressing concerns over a perceived danger to European values.[10] Political polarization increased,[11] confidence in the European Union fell,[12] and many countries tightened their asylum laws. Right-wing populist parties capitalized on public anxiety and became significantly more popular in many countries. There was an increase in protests regarding immigration and the circulation of the white nationalist conspiracy theory of the Great Replacement.[13] Nonetheless, despite the political consequences, a 2023 study leveraging quantified economic metrics (such as chained GDP and the inflation rate) concluded that the events ultimately resulted in a “low but positive impact” to the German economy.[14]

Terminology

editNews organisations and academic sources use both migrant crisis and refugee crisis to refer to the 2015 events, sometimes interchangeably. Some argued that the word migrant was pejorative or inaccurate in the context of people fleeing war and persecution because it implies most are emigrating voluntarily rather than being forced to leave their homes.[15][16] The BBC[17] and The Washington Post[18] argued against the stigmatization of the word, contending that it simply refers to anyone moving from one country to another. The Guardian said while it would not advise against using the word outright, "'refugees', 'displaced people' and 'asylum seekers' ... are more useful and accurate terms than a catch-all label like 'migrants', and we should use them wherever possible."[19] Al Jazeera, on the other hand, expressly avoided the term migrant, arguing it was inaccurate and risked "giving weight to those who want only to see economic migrants".[16] Some have taken issue with the framing of the phenomenon as a "crisis." Political scientist Cas Mudde has argued that the term reflects "more a matter of personal judgment than objective condition," writing that "[t]he EU had the financial resources to deal with even these record numbers of asylum seekers, although for years it had neglected to build an infrastructure to properly take care of them."[20]

Causes of increased number of asylum seekers

editThe most significant root causes of the wave of refugees entering Europe in 2015 were several interrelated wars, most notably the Libyan civil war, Syrian civil war and the 2014–2017 War in Iraq.

Background

editIn 2014, the EU member states counted around 252,000 irregular arrivals and 626,065 asylum applications,[21][22] the highest number since the 672,000 applications received in the wake of the Yugoslav Wars in 1992. Four countries – Germany, Sweden, Italy and France – received around two-thirds of the EU's asylum applications. Sweden, Hungary and Austria were among the top recipients of EU asylum applications per capita, when adjusted for their own populations, with 8.4 asylum seekers per 1,000 inhabitants in Sweden, 4.3 in Hungary, and 3.2 in Austria.[23][24] The EU countries that hosted the largest numbers of refugees at the end of 2014 were France (252,000), Germany (217,000), Sweden (142,000) and the United Kingdom (117,000).[25]

In 2014, the main countries of origin of asylum seekers, accounting for almost half of the total, were Syria (20%), Afghanistan (7%), Eritrea (6%).[26] Most crossed the Mediterranean Sea from Libya.[27] The overall rate of recognition of asylum applicants was 45 per cent at the first instance and 18 per cent on appeal[28] although there were huge differences between EU states,[29] ranging from Hungary (accepted 9% of applicants) to Sweden (accepted 74%).[28]

Escaping from conflicts or persecution

editAccording to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, most of the people who arrived in Europe in 2015 were refugees fleeing war and persecution[30] in countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Eritrea: 84 per cent of Mediterranean Sea arrivals in 2015 came from the world's top ten refugee-producing countries.[31] Wars fueling the migrant crisis are the Syrian Civil War, the Iraq War, the War in Afghanistan, the War in Somalia and the War in Darfur. Refugees from Eritrea, one of the most repressive states in the world, fled from indefinite military conscription and forced labour.[32][33]

Below are the major regions of conflict that have resulted in the increase of asylum seekers in the European region.

| Sort | Region of origin | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syrian | Western Asia | 29% | 28% |

| Other | 26% | 28% | |

| Afghanistan | Central Asia | 14% | 15% |

| Iraq | Western Asia | 10% | 11% |

| Albanian | Southeast Europe | 5% | 2% |

| Eritrea | East Africa | 3% | 3% |

| Iran | Western Asia | 2% | 3% |

| Kosovo | Southeast Europe | 5% | – |

| Nigeria | West Africa | 2% | 4% |

| Pakistan | South Asia | 4% | 4% |

Kosovo

editMigration from Kosovo occurred in phases beginning from the second half of the 20th century. The Kosovo War (February 1998 – June 1999) created a wave. On 19 May 2011, Kosovo established the Ministry of Diaspora. Kosovo also established the Kosovo Diaspora Agency (KDA) to support migrants.

The unemployment rate in Kosovo in 2014 was estimated at 30%, a majority of the unemployed being in the age range 15–24.[35] This was reflected in the age range of the emigrants, roughly 50% of whom were youth between the age of 15–24.[36] Detected illegal border crossings to the EU from Kosovo numbered 22,069 in 2014 and 23,793 in 2015.[37] The anti-government protests of 2015 coincided with a surge in migrant numbers.[38]

Syrian civil war

editThe Syrian civil war began in response to the Arab Spring protests of March 2011, which quickly escalated into a civil uprising. By May 2011, thousands of people had fled the country and the first refugee camps opened in Turkey. In March 2012, the UNHCR appointed a Regional Coordinator for Syrian Refugees, recognising the growing concerns surrounding the crisis. As the conflict descended into full civil war, outside powers, notably Iran, Turkey, the United States and Russia funded and armed different sides of the conflict and sometimes intervened directly.[39] By March 2013, the total number of Syrian refugees reached 1,000,000,[40] the vast majority of whom were internally displaced within Syria or had fled to Turkey or Lebanon; smaller numbers had sought refuge in Iraq and Egypt.[41]

War in Afghanistan

editAfghan refugees constitute the second-largest refugee population in the world.[42] According to the UNHCR, there are almost 2.5 million registered refugees from Afghanistan. Most of these refugees fled the region due to war and persecution. The majority have resettled in Pakistan and Iran, though it became increasingly common to migrate further west to the European Union. Afghanistan faced over 40 years of conflict dating back to the Soviet invasion in 1979. Since then, the nation faced fluctuating levels of civil war amidst unending unrest. The increase in refugee numbers was primarily attributed to the Taliban presence within Afghanistan. Their retreat in 2001 led to nearly 6 million Afghan refugees returning to their homeland. However, after the Taliban insurgency against NATO-led forces and subsequent Fall of Kabul, nearly 2.5 million refugees fled Afghanistan.[43]

Boko Haram insurgency

editThe Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria has resulted in the deaths of 20,000 people and displaced at least 2 million since 2009.[44] Around 75,000 Nigerians requested asylum in the EU in 2015 and 2016, around 3 per cent of the total.[34]

Means of entry into Europe

editIn all, over 1 million refugees and migrants crossed the Mediterranean (mostly the Aegean Sea) in 2015, three to four times more than the previous year.[46] 80% were fleeing from wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.[47] About 85% of sea arrivals were in Greece (via Turkey) and 15% in Italy (via northern Africa). The European Union's external land borders (e.g., in Greece, Bulgaria or Finland) played only a minor role.[48]

Some also crossed via the Central Mediterranean Sea. This path is a much longer and considerably more dangerous journey than the relatively short trip across the Aegean. As a result, this route was responsible for a large majority of migrant deaths in 2015, even though it was far less used. An estimated 2,889 died in the Central Mediterranean; 731 died in the Aegean sea.[48]

The EU Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) uses the terms "illegal" and "irregular" border crossings for crossings of an EU external border but not at an official border-crossing point.[49] These include people rescued at sea.[50] Because many migrants cross more than one external EU border (for instance when traveling through the Balkans from Greece to Hungary), the total number of irregular EU external border crossings is often higher than the number of irregular migrants arriving in the EU in a year. News media sometimes misrepresent these figures as given by Frontex.[27]

Turkey to Greece

editBecause the refugees entering Europe in 2015 were predominantly from the Middle East, the vast majority first entered the EU by crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece by boat; Turkey's land border has been inaccessible to migrants since a border fence was constructed there in 2012.[51] A number of Greek islands are less than 6 km (4 mi) from the Turkish coast, such as Chios, Kos, Lesbos, Leros, Kastellorizo, Agathonisi, Farmakonisi, Rhodes, Samos and Symi. At one point, incoming refugees on some of these islands outnumbered locals.[52]

A small number of people (34,000 or 3% of the total) used Turkey's land borders with Greece or Bulgaria.[48] From Greece, most tried to make their way toward through the Balkans to Central and Northern Europe.[53] This represented a stark change to the previous year, when most refugees and migrants landed in Italy from northern Africa. In fact, in the first half of 2015, Italy was, as in previous years, the most common landing point for refugees entering the EU, especially the southern Sicilian island of Lampedusa. By June, however, Greece overtook Italy in the number of arrivals and became the starting point of a flow of refugees and migrants moving through Balkan countries to Northern European countries, particularly Germany and Sweden. By the end of 2015, about 80% of migrants had landed in Greece, compared to only 15% in Italy.[31]

Greece appealed to the European Union for assistance; the UNCHR European Director Vincent Cochetel said facilities for migrants on the Greek islands were "totally inadequate" and the islands were in "total chaos".[54] Frontex's Operation Poseidon, aimed at patrolling the Aegean Sea, was underfunded and undermanned, with only 11 coastal patrol vessels, one ship, two helicopters, two aircraft, and a budget of €18 million.[55]

A section of northeastern Croatia is believed to contain up to 60,000 unexploded land mines from the Croatian War of Independence in the 1990s. Refugees were feared to be at risk of unknowingly detonating some of these minefields as they crossed the area. However, there were no reported cases of this happening in 2015 or 2016.[56]

Northern Africa to Italy

editThe number of people making the considerably more dangerous sea journey from northern Africa to Italy was comparatively low at around 150,000.[48] Most of the refugees and migrants taking this route came from African countries, especially Eritrea, Nigeria, and Somalia.[57] At least 2,889 people died during the journey.[48]

Other routes

editA few other routes were also used by some refugees, although they were comparatively low in number. One such route was entering Finland or Norway via Russia; on a few days Arctic border stations in these countries saw several hundred "irregular" border crossings per day.[58] Norway recorded around 6,000 refugees crossing its northern border in 2015.[59] Because it is illegal to drive from Russia to Norway without a permit, and crossing on foot is prohibited, some used a legal loophole and made the crossing by bicycle.[60][61] A year later in 2016, Norway built a short 200 m fence at the Storskog border crossing,[62] although it was viewed as a mostly symbolic measure.[63]

Some observers argued that the Russian government facilitated the influx in an attempt to warn European leaders against maintaining sanctions imposed after Russia's annexation of Crimea.[58][64] In January 2016, a Russian border guard admitted that the Russian Federal Security Service was enabling migrants to enter Finland.[65]

Role of smugglers

editBecause asylum seekers are usually required to be physically present in the EU country where they wish to request asylum, and there are few formal ways to allow them to reach Europe to do so,[66] many paid smugglers for advice, logistical help and transportation through Europe, especially for sea crossings.[67] Human traffickers charged $1,000 to $1,500 (€901 – €1352) for the 25-minute boat ride from Bodrum, Turkey to Kos.[68] An onward journey, not necessarily relying on smugglers, to Germany was estimated to cost €3,000 – €4,000 and €10,000 – €12,000 to Britain.[68] Airplane tickets directly from Turkey to Germany or Britain would have been far cheaper and safer, but the EU requires airlines flying into the Schengen Area to check that passengers have a visa or are exempted from carrying one ("carriers' responsibility").[69] This prevented would-be migrants without a visa from being allowed on aircraft, boats, or trains entering the Schengen Area, and caused them to resort to smugglers.[70] Humanitarian visas are generally not given to refugees who want to apply for asylum.[71]

In September 2015, Europol estimated there were 30,000 suspected migrant smugglers operating in and around Europe. By the end of 2016, this number had increased to 55,000. 63 per cent of the smugglers were from Europe, 14 per cent from the Middle East, 13 per cent from Africa, nine per cent from Asia (excluding the Middle East) and one per cent from the Americas.[72]

On several occasions, unscrupulous smugglers caused the deaths of the people they were transporting, particularly by using poorly-maintained and overfilled boats and refusing to provide life jackets.[68][73] At least 3771 refugees and migrants drowned in the Mediterranean Sea in 2015. A single shipwreck near Lampedusa in April accounted for around 800 deaths.[74] Apart from drownings, the deadliest incident occurred on 27 August 2015, when 71 people were found dead in an unventilated food truck near Vienna.[75][76] Eleven of the smugglers responsible were later arrested and charged with murder and homicide in Hungary. The charges and trial took place in Hungary as authorities determined that the deaths had occurred there.[76]

The Mafia Capitale investigation revealed that the Italian Mafia profited from the migrant crisis and exploited refugees.[77][78]

Peak of the crisis

editGraphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Gradual surge in early 2015

editThe first half of 2015 saw around 230,000 people enter the EU. The most common points of entry were Italy and Greece.[81] From there, arrivals either applied for asylum directly or attempted to travel to Northern and Western European countries, mostly by traveling through the Balkans and re-entering the EU through Hungary or Croatia.

Hungary was required by EU law to register them as asylum seekers and attempted to prevent them from traveling on to other EU countries.[citation needed] At the same time, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán began using fear of immigration as a domestic political campaign issue[82][83] and stated his opposition to accepting long-term refugees.[84] By August 2015, Hungary housed about 150,000 refugees[85] in makeshift camps.[86] Many had little desire to stay in Hungary; due to the government's unwelcoming stance, squalid conditions in the camps, and their poor prospects of being allowed to stay.[87] Over the course of 2015 and 2016, almost everyone who had lodged an asylum claim in Hungary left the country.[88][89]

On 21 August 2015, the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees was overwhelmed. This was attributed to the sheer mass of incoming asylum applications, the inherent complexity of determining whether applicants had previously claimed asylum in another EU country, and that almost all asylum applications by Syrians were being granted anyway[citation needed]

Due to their lack of capacity to process applications the German office suspended the Dublin Regulation for Syrians.[90][91] Interpreting this to mean that Germany would begin accepting larger numbers of refugees many immigrants attempted to reach Germany from Hungary and southeastern Europe.[92] They were met with a warm reception from the German crowds.[93]

September–November 2015: peak of the crisis

editGermany accepts refugees stranded in Hungary

editOn 1 September, Hungarian government closed outbound rail traffic from Budapest's Keleti station, which many refugees were using to travel to Austria and Germany.[94] Within days, a massive buildup of people had formed at the station. On 4 September, several thousand set off to make the 150 km journey towards Austria on foot, at which point the Hungarian government relented and no longer tried to stop them. In an effort to force the Austrian and German governments' hands, Hungary chartered buses to the Austrian border for both those walking and those who had stayed behind at the station.[95] Unwilling to resort to violence to keep them out, and faced with a potential humanitarian crisis if the huge numbers languished in Hungary indefinitely,[92][96] Germany and Austria jointly announced on 4 September that they would allow the migrants to cross their borders and apply for asylum.[97][98] Across Germany, crowds formed at train stations to applaud and welcome the arrivals.[99]

In the following three months, an estimated 550,000 people entered Germany to apply for asylum, around half the total for the entire year.[100] Though under pressure from conservative politicians, the German government refused to set an upper limit to the number of asylum applications it would accept, with Angela Merkel arguing that the "fundamental right to seek refuge...from the hell of war knows no limit."[101] She famously declared her confidence that Germany could cope with the situation with "wir schaffen das" (roughly, "we can manage this"). This phrase quickly became a symbol of her government's refugee policy.[102]

Chaotic border closures in central Europe

editWithin ten days of Germany's decision to accept the refugees in Hungary, the sudden influx had overwhelmed many of the major refugee processing and accommodation centres in Germany and the country began enacting border controls[103] and allowing people to file asylum applications directly at the Austrian border.[104] Although Austria also accepted some asylum seekers, for a time the country effectively became a distribution centre to Germany, slowing and regulating their transit into Germany and providing temporary housing, food and health care.[105] On some days, Austria took in up to 10,000 Germany-bound migrants arriving from Slovenia and Hungary.[106]

Germany's imposition of border controls had a domino effect on countries to Germany's southeast, as Austria and Slovakia successively enacted their own border controls.[107][108] Hungary closed its border with Serbia entirely with a fence that had been under construction for several months, forcing migrants to pass through Croatia and Slovenia instead.[109] Croatia tried to force them back into Hungary, which responded with military force.[110] Croatian and Hungarian leaders each blamed each other for the situation and engaged in a bitter back-and-forth about what to do about the tens of thousands of stranded people.[110] Three days later, Croatia likewise closed its border with Serbia to avoid becoming a transit country.[111] Slovenia kept its borders open, although it did limit the flow of people, resulting in occasionally violent clashes with police.[112]

In October, Hungary also closed its border with Croatia, making Slovenia the only remaining way to reach Austria and Germany. Croatia reopened its own border to Serbia[113] and together with Slovenia began permitting migrants to pass through, providing buses and temporary accommodation en route.[114] Slovenia did impose a limit of 2,500 people per day, which initially stranded thousands of migrants in Croatia, Serbia and North Macedonia.[115][116] In November, Slovenia began erecting temporary fences along the border to direct the flow of people to formal border crossings.[117] Several countries, such as Hungary,[118] Slovenia[119] and Austria,[120] authorized their armies to secure their borders or repel migrants; some passed legislation specifically to give armed forces more powers.[121]

EU officials generally reacted with dismay at the border closures, warning that they undermined the mutual trust and freedom of movement that the bloc was founded on and risked returning to a pre-1990s arrangement of costly border controls and mistrust. The European Commission warned EU members against steps that contravene EU treaties and urged members like Hungary to find other ways to cope with an influx of refugees and migrants.[122]

As winter set in, refugee numbers decreased, although they were still many times higher than in the previous year. In January and February 2016, over 123,000 migrants landed in Greece, compared to about 4,600 in the same period of 2015.[123]

Refugees in Sweden

editSweden took in over 160,000 refugees in 2015, more per capita than any other country in Europe (other than Turkey). Well over half of these came to Sweden in October and November.[124] Most entered Sweden by traveling through Germany and then Denmark; few wanted to apply for asylum in Denmark because of its comparatively harsh conditions for asylum seekers.[125] There were occasionally scuffles as Danish police tried to register some of the arrivals, as they were technically required to do according to EU rules.[126][127] In early September, Denmark temporarily closed rail and road border crossings with Germany.[128] After initial uncertainty surrounding the rules, Denmark allowed most of the people wishing to travel on to Sweden to do so.[129] In the five weeks following 6 September, approximately 28,800 refugees and migrants crossed the Danish borders, 3,500 of whom applied for asylum in Denmark; the rest continued to other Nordic countries.[130]

In November 2015, Sweden reintroduced border controls at the Danish border, although this did not reduce the number of arrivals as they still had the right to apply for asylum.[131] Within hours of Swedish border control becoming effective, Denmark instituted border controls at the German border.[132] Some bypassed the border controls by taking a ferry to Trelleborg instead of the train to Hyllie,[133][132] The border controls were never fully lifted before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, which saw renewed border closures throughout Europe.

Diplomatic incidents

editIn October 2015, the Slovenian government accused Croatian police of helping migrants bypass Slovene border controls and released a night time thermovision video allegedly documenting the event.[134][135]

Housing conditions

editAfter inspecting a refugee camp in Traiskirchen, Austria, in August 2015, Amnesty International noted inhabitants were receiving insufficient medical care and claimed Austria was "violating human rights".[136]

In late November, Finnish reception centers were running out of space, which forced authorities to resort to refurbished shipping containers and tents to house new asylum seekers.[137] Deputy prime minister Petteri Orpo announced that special repatriation centers would be established to house denied asylum seekers. While he stressed that these camps would not be prisons, he described the inhabitants would be under strict surveillance.[138]

Many migrants tried to enter the United Kingdom, resulting in camps of migrants around Calais where one of the Eurotunnel entrances is located. In the summer of 2015, at least nine people died in attempts to reach Britain, including falling from trains, being hit by trains, or drowning in a canal at the Eurotunnel entrance.[139] In response, a UK-financed fence was built along the A-216 highway in Calais.[140][141] At the camp near Calais, known as the Jungle, riots broke out when authorities began demolishing the illegally constructed campsite on 29 January 2015.[142] Amid the protests, which included hunger strikes, thousands of refugees living in the camp were relocated to France's "first international-standard refugee camp" at the La Liniere refugee camp in Grande-Synthe which replaced the previous Basroch refugee camp.[143]

Germany has a quota system to distribute asylum seekers among all German states, but in September 2015 the federal states, responsible for accommodation, criticised the government in Berlin for not providing enough help to them.

In Germany, which took in by far the highest number of refugees, the federal government distributes refugees among the 16 states proportionally to their tax revenue and population;[144] the states themselves are required to come up with housing solutions. In 2015, this arrangement came under strain as many states ran out of dedicated accommodation for incoming refugees.[145] Many resorted to temporarily housing refugees in tents or repurposed empty buildings. The small village of Sumte (population 102), which contained a large unused warehouse, famously took in 750 refugees.[146] Although media and some locals feared racial strife and a far-right political surge, the town remained peaceful and locals largely accepting. By 2020, most of the arrivals had moved on to bigger German cities for work or study; a small number settled in Sumte permanently.[147] In Berlin, authorities housed refugees in temporary accommodations at the site of the decommissioned Tempelhof Airport, then developed a program of container housing known as Tempohomes, followed by Modular Accommodations for Refugees (Modulare Unterkünfte für Flüchtlinge); many of the Tempohomes and MUF are still in use as of 2022, and some have begun housing Ukrainian refugees as well.[148]

EU-Turkey refugee return agreement

editBecause the vast majority of refugees arriving in Europe in 2015 passed through Turkey, the country's cooperation was seen as central to efforts to stem the flow of people and prevent refugees from attempting to make dangerous sea crossings. There was also a recognition that it would be unfair to expect Turkey to shoulder the financial and logistical burden of hosting and integrating millions of refugees on its own. In 2015, the European Commission began negotiating an agreement with Turkey to close its borders to Greece in exchange for money and diplomatic favours. In March 2016, after months of tense negotiations[149] during which Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan repeatedly threatened to open Turkey's borders and "flood" Europe with migrants to extract concessions,[150] a deal was announced. Turkey agreed to significantly increase border security at its shores and take back all future irregular entrants into Greece (and thereby the EU) from Turkey. In return, the EU would pay Turkey 6 billion euros (around US$7 billion).[151] In addition, for every Syrian sent back from Greece, the EU would accept one registered Syrian refugee living in Turkey who had never tried to enter the EU illegally, up to a total of 72,000. If the process succeeded in dramatically reducing irregular immigration to a maximum of 6,000 people per month, the EU would set up a resettlement scheme by which it would regularly resettle Syrian refugees registered in Turkey and upon vetting and recommendation by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The EU also promised to institute visa-free travel to the Schengen area and to breathe new life into Turkey's EU accession talks.[152]

The deal came into force on 20 March 2016.[153] On 4 April, the first group of 200 people had been deported from Greece to Turkey under the provisions of the deal. Turkey planned to deport most of them to their home countries.[154] The agreement resulted in a steep decline of migrant arrivals in Greece; in April, Greece recorded only 2,700 irregular border crossings, a 90 per cent decrease compared to the previous month.[155] This was also the first time since June 2015 that more migrants arrived in Italy than in Greece.[155]

The plan to send migrants back to Turkey was criticized by human right organisations and the United Nations, which warned that it could be illegal to send the migrants back to Turkey in exchange for financial and political rewards.[156] The UNHCR said it was not a party to the EU-Turkey deal and would not be involved in returns or detentions.[157] Like the UNHCR, four aid agencies (Médecins Sans Frontières, the International Rescue Committee, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children) said they would not help to implement the EU-Turkey deal because blanket expulsion of refugees contravened international law.[158] Amnesty International called the agreement "madness", and said 18 March 2016 was "a dark day for Refugee Convention, Europe and humanity". Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu said that Turkey and EU had the same challenges, the same future, and the same destiny. President of the European Council Donald Tusk said that the migrants in Greece would not be sent back to dangerous areas.[159]

Turkey's EU accession talks began in July 2016 and the first $3.3 billion was transferred to Turkey.[153] The talks were suspended in November 2016 after the Turkey's antidemocratic response to the 2016 Turkish coup attempt.[160] Erdoğan again threatened to flood Europe with migrants after the European Parliament voted to suspend EU membership talks in November 2016: "if you go any further, these border gates will be opened. Neither me nor my people will be affected by these dry threats."[161][162] Over the next few years, Turkish officials continued to threaten the EU with reneging on the deal and engineering a repeat of the 2015 refugee crisis in response to criticism of the Erdoğan government.[163][164] In one notable incident in March 2020, the Turkish government bused large numbers of Syrians living in Turkey to the Greek border and encouraged them to cross. Greece repelled the arrivals with border guards.[165][166]

One effect of the closure of the "Balkan route" was to drive refugees to other routes, especially across the central and eastern Mediterranean. As a result, migrant deaths due to shipwrecks began increasing again. On 16 April, a large boat sank between Libya and Italy, with as many as 500 deaths.[167] In addition, countries that had seen comparatively few refugee arrivals began recording significant numbers. In 2017, for instance, there was a 60% significant jump in the number of migrants reaching Spain.[168] Similarly, Cyprus recorded an approximately 8-fold increase in the number of arrivals between 2016 and 2017.[169][170]

In response to the increased numbers of people reaching Italian shores, Italy signed an agreement in early 2017 with the UN-recognized government of Libya, from where most migrants started their boat journeys to Italy. In return for Libya making more efforts to prevent migrants from reaching Europe, Italy provided money and training for the Libyan coast guard and for migrant detention centres in northern Libya. In August of that year, the Libyan Coast Guard began requiring NGO rescue vessels to stay at least 360 km (225 mi) from the Libyan coast unless they were given express permission to enter.[171] As a result, NGOs MSF, Save the Children and Sea Eye suspended their operations after clashes with the Libyan Coast Guard after the latter asserted its sovereignty of its waters by firing warning shots.[67] Soon afterwards, refugee arrivals in Italy dropped significantly. At the same time, the lack of rescue vessels made the crossing much more dangerous; by September 2018, one in five migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Libya either drowned or disappeared.[172] In 2019, the deal was renewed for a further three years.[173]

| Country | Total processed asylum applications in 2015–17[b] |

|---|---|

| Germany | |

| France | |

| Italy | |

| Sweden | |

| Austria | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Belgium | |

| Netherlands | |

| Switzerland | |

| Greece | |

| Norway | |

| Finland | |

| Denmark | |

| Spain | |

| Bulgaria | |

| Hungary | |

| Poland | |

| Cyprus | |

| Romania | |

| Malta | |

| Ireland | |

| Czech Republic | |

| Luxembourg | |

| Portugal | |

| Croatia | |

| Lithuania | |

| Latvia | |

| Slovenia | |

| Estonia |

EU response

editThe response at the EU level was relatively uncoordinated, as some member states unilaterally closed their borders and others, like Germany and Sweden, maintained a relatively welcoming stance. The sudden border closures often resulted in chaos, trapping large numbers of people in countries where they had no desire to stay.

The European Commission made some attempts to harmonize the different policies, such as the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). In addition, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency focused on strengthening European border integrity in the Mediterranean Sea. Several policies, such as an "Emergency Trust Fund," were also developed to address problems in the home countries of asylum seekers.

Role of non-governmental organizations

editNon-governmental organizations often filled the vacuum official operations were insufficient.[176] Following the end of Italy's Mare Nostrum operation in 2014, NGOs began performing search and rescue operations.[177] Some Italian authorities feared that they encouraged people to use the dangerous passage facilitated by human traffickers.[178][179] In July 2017, Italy drew up a code of conduct for NGO rescue vessels delivering migrants to Italian ports.[180] These rules prohibited coordinating with human traffickers via flares or radio and required vessels to permit police presence on board. More controversially, they also forbade entering the territorial waters of Libya and transferring rescued people onto other vessels, which severely limited the number of people NGOs could save.[181] The Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International criticised the code of conduct and some NGOs, including Doctors Without Borders, eventually suspended rescue operations.[178] In the years following its implementation, Mediterranean Sea crossings dropped considerably, although the degree to which this was caused by the NGO code is disputed. A study conducted from 2014 to 2019 concluded that external factors like weather and the political stability of Libya contributed more to the ebbs and flows of migrants crossing the Mediterranean.[182] Non-governmental search and rescue operations cannot entirely stop the loss of life at sea in the wake of large-scale migratory flows.[179]

In September 2016, Greek volunteers of the "Hellenic Rescue Team" and human rights activist Efi Latsoudi were awarded the Nansen Refugee Award by the UNHCR "for their tireless volunteer work" in helping refugees arrive in Greece during the 2015 refugee crisis.[183]

Public opinion

editA 2016 study by Pew Research Center suggested widespread anxiety over the refugee crisis and immigration in general, particularly about effects on the labour market, crime, and difficulty integrating the newcomers. The study also revealed insecurities about weakening national identities when taking in people from other cultures.[184]

Many Europeans also harbored more specific anxieties around Muslim immigration with a fear that Islam is incompatible with European values.[10] Some national leaders, notably in Slovakia and Hungary, exploited and at times encouraged this fear for electoral gain.[185] A study of ten European countries by Royal Institute of International Affairs found that an average of 55% would support stopping further immigration from Muslims, with support ranging from 40% (Spain) to 70% (Poland).[186] A study by the European Social Survey using more nuanced wording found that 25% were opposed to all Muslim immigration; a further 30% supported permitting only "some" Muslim immigration.[187]

The public perception of the migrant crisis from the Hungarian point of view characterized as anti-immigration since 2015. Muslim immigrants are perceived as a symbolic threat to the dominant—mostly Christian—Western culture and [specifically in the Hungarian context] asylum seekers with a Christian background are more welcomed than those with a Muslim background.[188]

A study released by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights found out that almost 40% of first and second-generation Muslims in Europe surveyed reported discrimination in their daily life.[189]

British Somali poet Warsan Shire's poem 'Home' became a prominent depiction of the refugee experience. A video of Benedict Cumberbatch reciting the poem after a stage performance as part of an impassioned plea to help refugees went viral in September 2015.[190]

Death of Alan Kurdi

editA photo of the body of a 3-year-old Syrian boy named Alan Kurdi (after he drowned on 2 September 2015) became a symbol of the suffering of refugees trying to reach Europe.[191] Unlike many pictures of refugees often published in European media, in which "asylum-seekers are generally shown in groups of people, often on boats, rather than as single individuals", the picture was of a single, identifiable child victim and engendered a wave of compassion throughout Europe.[192] Multiple EU leaders addressed the photo and called for EU action to address the crisis.[193][194] Kurdi and his family were Syrian refugees, and 3-year-old Alan died alongside his brother and mother – only his father survived the journey, telling CNN "everything I was dreaming of is gone. I want to bury my children and sit beside them until I die."[194] Kurdi's body was photographed by Turkish journalist Nilüfer Demir.

Pro and anti-immigration protests

editPegida, a pan-European far-right political movement founded in 2014 on opposition to immigration from Muslim countries, experienced a resurgence during the refugee crisis, especially in eastern Germany. The movement said that "Western civilisation could soon come to an end through Islam conquering Europe".[195] In the United Kingdom, members of the far-right anti-immigration group Britain First organised protest marches.[196] An analysis by Hope not Hate, an anti-racist advocacy group, identified 24 different British groups attempting to whip up mistrust of Muslims and provoke a "cultural civil war", including the UK chapter of Pegida and the political party Liberty GB.[197]

White-nationalist conspiracy theories predicting a Muslim takeover of Europe gained wider prominence during and after the refugee crisis.[198] A theory known as Eurabia, which claims that globalist entities led by French and Arab powers are plotting to "islamise" and "arabise" Europe, was propagated widely in far-right circles.[199] Many groups also circulated a similar conspiracy theory called the "Great Replacement".[13]

Other notable anti-immigration protests in the aftermath of 2015, some of which escalated to riots, included:

- 16 December 2015: riot in Geldermalsen, The Netherlands, at a town hall meeting to discuss a new housing complex for 1,500 asylum seekers.[200]

- 25 December 2015: protests by Corsican nationalists, officially in support of Corsican autonomy, but which saw a mob ransack a Muslim prayer hall in Ajaccio and people burn Qurans. The rioters had assumed that a recent crime in the town had been carried out by immigrants.[201]

- 26 August 2018: Protests and subsequent violence in Chemnitz, Germany[202]

Notable pro-refugee or pro-immigration protests in response to the refugee crisis included:

- 15 June 2015: Birlikte, a series of semi-annual rallies and corresponding cultural festivals against right-wing extremist violence in Germany[203][204]

- 12 September 2015: "day of action" in several European cities in support of refugees and migrants, several 10,000 participants.[205] On the same day, anti-immigration rallies took place in some eastern European countries.[205]

- 18 February 2017: Volem acollir ("we want to welcome") protest in Barcelona, 160,000–500,000 participants[206]

Statistics

editMore than 3,700 migrants died trying, usually by drowning.[207]

Asylum applications

edit| Origin | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Syria | ||

| Afghanistan | ||

| Iraq | ||

| Pakistan | ||

| Nigeria | ||

| Iran | ||

| Eritrea | ||

| Russia | ||

| Unknown | ||

| Rest of the world |

Over 75% of asylum seekers arriving in Europe in 2015 were fleeing from Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq.[211] Other significant countries of origin were Pakistan and Eritrea.[212]

Around half of asylum applications were made by young adults between 18 and 34 years of age; 96,000 refugees were unaccompanied minors. Around three-quarters of applications were by men.[213] The gender imbalance among refugees reaching Europe has multiple related causes, most significantly the dangerous and expensive nature of the journey. Men with families often travel to Europe alone with the intent of applying for family reunification once their asylum request is granted.[214] In addition, in many countries, such as Syria, men are at greater risk than women of being forcibly conscripted or killed.[215]

Developing countries hosted the largest share of refugees (86 per cent by the end of 2014, the highest figure in more than two decades); the least developed countries alone provided asylum to 25 per cent of refugees worldwide.[25] Even though most Syrian refugees were hosted by neighbouring countries such as Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, the number of asylum applications lodged by Syrian refugees in Europe steadily increased between 2011 and 2015, totaling 813,599 in 37 European countries (including both EU members and non-members) as of November 2015; 57 per cent of them applied for asylum in Germany or Serbia.[216]

Acceptance rate of asylum requests

edit52 per cent of asylum applications in the EU were granted in 2015; another 14 per cent were granted on appeal. The citizenships with the highest recognition rates at first instance were Syria (97.2 per cent), Eritrea (89.8 per cent), Iraq (85.7 per cent), Afghanistan (67 per cent), Iran (64.7 per cent), Somalia (63.1 per cent) and Sudan (56 per cent).[218] Asylum applications by citizens of some countries with high levels of violence, like Nigeria and Pakistan, nevertheless had low success rates.

Economic migrants

editSome people applying for asylum were perceived to be economic migrants using the asylum process to move to Europe to find work, rather than fleeing war or persecution. Economic migrants are not eligible for asylum, although the distinction between economic migrants and refugees is not always clear since some people fleeing war are also fleeing poverty.[219] It is difficult to say what proportion of the 2015 arrivals to Europe were "economic migrants." Some analysts use refugee recognition rates as a metric,[220] although this is also difficult since these vary widely between EU countries.[221]

People from the Western Balkans — most of whom were Romanis, a marginalized ethnic group[222] — were often perceived to be economic migrants.[223] Parts of West Africa and Pakistan also had low recognition rates.[224][225] However, these nationalities made up a relatively small percentage of 2015 arrivals. In 2015, 14% of all first-time asylum requests filed in the EU were by people from the Western Balkans; in 2016 the figure was 5%.[217] Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis, whose asylum recognition rates ranged between 60% and 100% in Germany (which accepted by far the largest number of refugees in 2015) together filed around half of all asylum requests in both years.[221]

Some argue that migrants have been seeking to settle preferentially in national destinations that offer more generous social welfare benefits and host more established Middle Eastern and African immigrant communities. Others argue that migrants are attracted to more tolerant societies with stronger economies, and that the chief motivation for leaving Turkey is that they are not permitted to leave camps or work.[226] A large number of refugees in Turkey have been faced with difficult living circumstances;[227] thus, many refugees arriving in southern Europe continue their journey in attempts to reach northern European countries such as Germany, which are observed as having more prominent outcomes of security.[228] In contrast to Germany, France's popularity eroded in 2015 among migrants seeking asylum after being historically considered a popular final destination for the EU migrants.[229][230]

International reactions

editIn September 2015, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg noted that NATO could play a long-term role stabilizing war-torn countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and in Afghanistan, but that "immediate measures, border, migrant, the discussion about quotas, so on – [are] civilian issues, addressed by the European Union."[231]

The Russian Federation released an official statement on 2 September 2015 reporting that the United Nations Security Council was working on a draft resolution to address the European migrant crisis, likely by permitting the inspection of suspected migrant ships.[232]

The International Organization for Migration claimed that deaths at sea increased ninefold after the end of Operation Mare Nostrum.[233] Amnesty International condemned European governments for "negligence towards the humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean" which they say led to an increase in deaths at sea.

In April 2015, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch criticised the funding of search and rescue operations. Amnesty International said that the EU was "turning its back on its responsibilities and clearly threatening thousands of lives".[234][235]

Australian prime minister Tony Abbott said the tragedies were "worsened by Europe's refusal to learn from its own mistakes and from the efforts of others who have handled similar problems. Destroying the criminal people-smugglers was the centre of gravity of our border control policies, and judicious boat turnbacks was the key."[236]

Then-U.S. President Barack Obama praised Germany for taking a leading role in accepting refugees.[237] During his April 2016 visit to Germany, he praised German Chancellor Angela Merkel for being on "the right side of history" with her open-border immigration policy.[238]

In a report released in January 2016, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) denounced the EU response to the refugee crisis in 2015 and said that policies of deterrence and chaotic response to the humanitarian needs of those who fled actively worsened the conditions of refugees and migrants and created a "policy-made humanitarian crisis". According to MSF, obstacles placed by EU governments included "not providing any alternative to a deadly sea crossing, erecting razor wire fences, continuously changing administrative and registration procedures, committing acts of violence at sea and at land borders and providing completely inadequate reception conditions in Italy and Greece".[239]

In March 2016, NATO General Philip Breedlove stated, "Together, Russia and the Assad regime are deliberately weaponizing migration in an attempt to overwhelm European structures and break European resolve. .. These indiscriminate weapons used by both Bashar al-Assad, and the non-precision use of weapons by the Russian forces – I can't find any other reason for them other than to cause refugees to be on the move and make them someone else's problem."[240] He also expressed concern that criminals, extremists and ISIS fighters might be among the flow of migrants.[241]

On 18 June 2016, United Nations chief Ban Ki-moon also called for international support and praised Greece for showing "remarkable solidarity and compassion" towards refugees.[242][243] The lack of action by UNESCO in this area was the subject of controversy. Some scholars, like António Silva,[244] blamed UNESCO for not denouncing racism against war refugees in Europe with the same vigor as the vandalism against ancient monuments perpetrated by fundamentalists in the Middle East.[citation needed]

Aftermath

editFollowing the European Union's measures to prevent asylum seekers from reaching its borders, monthly arrivals dropped to around 10,000–20,000 in spring 2016. Arrival numbers fell in each of the following years, dropping to 95,000 by 2020.[245] Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan continued to occasionally threaten to renege on Turkey's agreement to prevent migrants and refugees from reaching Europe, often demanding more cash[246] or retaliating for European criticism of Turkey's human rights record.[247]

Effects on politics

editThe refugee crisis polarized European society. In Western Europe, large majorities supported accepting refugees fleeing violence and war, while Eastern Europeans were generally more ambivalent. At the same time, however, large majorities also disapproved of the EU's handling of the refugee wave.[11]

As southeastern European countries began seeing large numbers of refugees and migrants began moving through them, political leaders began to capitalize on the uncertainty felt by locals. The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, in particular began to campaign on fear of immigration, calling refugees "Muslim invaders",[248] conflating migrants with terrorism,[249] and stating that they were part of a "left-wing conspiracy" to gain new voters.[250] In October, Czech President Miloš Zeman used similar rhetoric to campaign on opposition to refugees.[251]

The refugee crisis was also a major issue in Poland's 2015 parliamentary elections, with then-opposition leader Jarosław Kaczyński in particular stoking fear of immigrants and claiming the EU was planning to flood Poland with Muslims. Under incumbent prime minister Ewa Kopacz, Poland had agreed to accept 2,000 refugees as part of the European Union's plan to distribute a fraction of that year's arrivals, while at the same time opposing the settlement of "economic migrants".[252] After Kaczyński's Law and Justice party won the elections, Poland rescinded its willingness to cooperate with the European Commission.[253]

Nigel Farage, leader of the British United Kingdom Independence Party, said that Islamists could exploit the situation and enter Europe in large numbers.[254][255] In western European countries, although support for refugees was generally high,[11] far-right leaders fiercely opposed allowing the newly arrived refugees to stay. Matteo Salvini, leader of Italy's League, described the migration as a "planned invasion" which must be stopped.[256] Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom, called the influx of people an "Islamic invasion" and spoke of "masses of young men in their twenties with beards singing Allahu Akbar across Europe".[257] Marine Le Pen, leader of the French far-right National Front, was criticized by German media[258][259] for implying that Germany was looking to undercut minimum wage laws and hire "slaves".[260]

Germany's acceptance of over 1 million asylum seekers was controversial both within Angela Merkel's centre-right Christian Democratic Union party and among the general public.[261] Pegida, an anti-immigration protest movement, flourished briefly in late 2014, followed by a new wave of anti-immigration protests in the late summer of 2015. Many members of parliament for the CDU voiced dissatisfaction with Merkel. Horst Seehofer, then premier of Bavaria, became a prominent critic within the CDU of Merkel's refugee policy[262] and alleged that as many as 30 per cent of Germany's asylum seekers claiming to be from Syria were in fact from other countries.[263] Yasmin Fahimi, secretary-general of the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), the junior partner of the ruling coalition, praised Merkel's policy allowing migrants in Hungary to enter Germany as "a strong signal of humanity to show that Europe's values are valid also in difficult times".[264]

In the 2017 German federal election, the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) gained 12% of the vote, which was attributed in part to anxieties around immigration.[265] A 2022 study by the Bertelsmann Foundation showed that positive and negative assessments have begun to "roughly balance each other out", with those surveyed for the study expressing concerns about additional burden on the welfare state and social conflict, while also hoping that the migrants "could solve Germany's demographic and economic problems.[266][267]

The Hungarian government under Fidesz held a referendum in 2016, where the overwhelming majority (98.4%) rejected the EU's mandatory migrant quotas, although the result was not considered valid because turnout fell short of the required 50% threshold, due to the opposition boycotting the referendum.

Effects on 2016 Brexit vote

editThe 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum took place on 23 June 2016, around nine months after peak of the refugee crisis. The UK was never a member of the Schengen Area and so experienced very few direct effects of the influx of migrants.[268] Nevertheless, Leave.EU, one of the two main groups campaigning in favour of Brexit, made the refugee crisis its defining issue (the other main pro-Leave group, Vote Leave, primarily focused on economic arguments). The campaign portrayed the European Union as inept and unable to control its borders, and conflated the refugee crisis with unease over Turkey's application to join the EU (although very few of the 2015 refugees were from Turkey).[12]

Theresa May, then Home Secretary (and later prime minister), though critical of the European Union's immigration policy, opposed Brexit and argued that the UK was already well-isolated from immigration crises occurring in the wider EU:

"Now I know some people say the EU does not make us more secure because it does not allow us to control our border. But that is not true. Free movement rules mean it is harder to control the volume of European immigration – and as I said yesterday that is clearly no good thing – but they do not mean we cannot control the border. The fact that we are not part of Schengen – the group of countries without border checks – means we have avoided the worst of the migration crisis that has hit continental Europe over the last year."

— Home Secretary, Theresa May[269]

The Brexit vote resulted in a narrow decision to leave the EU (51.9% to 48.1%). According to exit polls, one third of Leave voters believed leaving the EU would allow Britain to better control immigration and its own borders.[270]

Integration of refugees

editWhile figures specifically for refugees are often not available, they tend to be disproportionately unemployed compared to the local population, especially in the years immediately following their resettlement. OECD data comparing employment rates of local-born compared to foreign-born residents demonstrated large differences between countries. According to a 2016 article, it took foreign-born an average of 20 years to fully "catch up" with locals. In all countries except Italy and Portugal, immigrants had lower rates of employment compared to the local population, but considerable differences exist with respect to both host countries and countries of origin. In the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Germany, for instance, the gap was larger than in the UK, Italy and Portugal.[271]

Rejected asylum seekers

editPeople whose asylum applications are rejected are generally required to return to their home countries. Some do so voluntarily; others are deported. However, deportation is often difficult in practice; a common reason is lacking travel documents or the person's country of origin refusing to accept returnees.[272] The annual rate of return has generally averaged around one-third.[273] In some countries that took in large numbers of asylum seekers, this has resulted in tens of thousands of people not having legal residency rights, raising worries of institutionalised poverty and the creation of parallel societies.[274] The years following the 2015 refugee crisis saw some European countries enact legislation to speed up deportations.[275] The EU began threatening to withhold development aid from or impose visa restrictions on countries refusing to take in their own citizens.

For a variety of reasons, some rejected asylum seekers also ended up being permitted to stay. Some countries, such as Germany and Sweden, allow rejected asylum seekers to apply for certain other visas (e.g., to pursue vocational training if they have secured an apprenticeship).[276]

Tightening of asylum laws

editAround November 2015, some European countries restricted family reunions for refugees, and started campaigns to dissuade people worldwide to migrate to Europe. EU leaders also quietly encouraged Balkan governments to only allow nationals from the most war-torn countries (Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq) to pass into the EU.[277]

In 2016 Sweden began issuing three-year residence permits to recognized refugees. Refugees had previously received permanent residency automatically.[278]

In January 2016, Denmark passed a law permitting police to confiscate valuables like jewelry and cash from refugees. As of early 2019, the police had only enforced the cash-seizing provision.[279]

Post-traumatic stress

editRefugees, who have often fled violence their home countries and experienced further violence during their journey, have high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[280] In 2016 in Sweden, 30% of Syrian refugees were estimated to suffer from PTSD, depression, and anxiety.[281] In 2020, a study of physically healthy young refugees in Germany identified 40% as having risk factors for PTSD.[282] Long asylum claim processing times, during which refugees cannot work or travel and contemplate being sent back to their home country, often compound poor mental health.[283] Although asylum applications are in principle supposed to be processed within six months on average, many countries that took in significantly more refugees than in previous years took considerably longer – in many cases over year and sometimes up to two.[284]

In Germany, refugees do not have access to non-acute medical care, including therapy mental health treatments, until they have lived in the country for at least 15 months. Language barriers also often make therapy particularly difficult.[285]

Press coverage

editThe Cardiff School of Journalism, in a report on behalf of UNHCR, analysed several thousand media reports on the refugee crisis in Spain, Italy, United Kingdom, Germany and Sweden. In all countries, conservative tabloids and newspapers, such as the British Daily Mail, the Spanish ABC and the German Welt, were found to be more likely to emphasize perceived risks of extremists among arriving refugees, while centre-left publications were more likely to mention humanitarian aspects. A similar split was apparent in the reasons for people fleeing their home countries: right-wing newspapers were more likely to mention economic reasons than left-of-centre ones.[286]

The study also found significant differences between countries, noting that right-wing media in the United Kingdom had conducted a "uniquely aggressive campaign" against refugees and migrants in 2015. Threats to welfare systems and cultural threats were most prevalent in Italy, Spain, and Britain while humanitarian themes were more frequent in Italian coverage. More subtle differences in were found in the terminology used: German and Swedish media overwhelmingly used the terms refugee or asylum seeker while Italy and UK were more likely to use the term migrant. In Spain, the dominant term was immigrant. Overall the Swedish press was most positive towards the arrivals.[286]

Press coverage of German migration policies

editJournalist Will Hutton for the British newspaper The Guardian praised Angela Merkel's leadership during the refugee crisis: "Angela Merkel's humane stance on migration is a lesson to us all... The German leader has stood up to be counted. Europe should rally to her side... She wants to keep Germany and Europe open, to welcome legitimate asylum seekers in common humanity, while doing her very best to stop abuse and keep the movement to manageable proportions. Which demands a European-wide response (...)".[287]

Analyst Naina Bajekal for the United States' magazine Time in September 2015 suggested that the German decision to allow Syrian refugees to apply for asylum in Germany even if they had reached Germany through other EU member states in August 2015, led to increased numbers of refugees from Syria and other regions – Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Ukraine, Congo, South Sudan etc. – endeavouring to reach (Western) Europe.[288]

In March 2016, the UK's Daily Telegraph said that Merkel's 2015 decisions concerning migration represented an "open door policy", which it said was "encouraging migration into Europe that her own country is unwilling to absorb" and as damaging the EU, "perhaps terminally".[289]

See also

edit- African immigration to Europe

- Demographics of Europe

- Emigration from Africa

- EU Malta Declaration

- Free movement protocol

- Illegal immigration

- Immigration to Greece

- List of migrant vessel incidents on the Mediterranean Sea

- Migrants' African routes

- Petra László tripping incident

- Turkish migrant crisis

- Ukrainian refugee crisis

- Willkommenskultur

- With Open Gates

- Wir schaffen das

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Asylum quarterly report – Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Barlai, Melani; Fähnrich, Birte; Griessler, Christina; Rhomberg, Markus, eds. (2017). The migrant crisis: European perspectives and national discourses. Peter Filzmaier (preface). LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90802-5. OCLC 953843642. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Dumont, Jean-Christophe; Scarpet, Stefano (September 2015). "Is this humanitarian migration crisis different?" (PDF). Migration Policy Debates. OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Ayaz, Ameer; Wadood, Abdul (Summer 2020). "An Analysis of European Union Policy towards Syrian Refugees" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. 27 (2): 1–19. eISSN 2308-8338. ProQuest 2568033477. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "FACTBOX-How big is Europe's refugee and migrant crisis?". Thomson Reuters Foundation News. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: Explaining the exodus from the Balkans". BBC News. 8 September 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Zaragoza-Cristiani, Jonathan (2015). "Analysing the Causes of the Refugee Crisis and the Key Role of Turkey: Why Now and Why So Many?" (PDF). EUI Working Papers. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Hatton, Tim (2020). European asylum policy before and after the migration crisis (PDF). IZA World of Labor. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ a b Nugent, Neil (2017). "Setting the Scene: The 'Crises', the Challenges, and Their Implications for the Nature and Operation of the EU". The government and politics of the European Union (8th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-137-45409-6.

- ^ a b Bowen, John (2014). European states and their Muslim citizens : the impact of institutions on perceptions and boundaries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03864-6.

- ^ a b c Connor, Phillip (19 September 2018). "Europeans support taking in refugees – but not EU's handling of issue". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b Outhwaite, William (28 February 2019). Menjívar, Cecilia; Ruiz, Marie; Ness, Immanuel (eds.). "Migration Crisis and "Brexit"". The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises. Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190856908.001.0001. ISBN 9780190856908. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b Williams, Thomas Chatterton. "The French Origins of "You Will Not Replace Us"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Solinsky, Irish (3 February 2023). "The 2015 Migrant Crisis: An Impact to Germany?". Doctoral Dissertations and Projects.

- ^ Rachman, Gideon (3 September 2015). "Refugees or migrants – what's in a word?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ a b Malone, Barry (20 August 2015). "Why Al Jazeera will not say Mediterranean 'migrants'". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Ruz, Camila (28 August 2015). "The battle over the words used to describe migrants". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (22 August 2015). "Is it time to ditch the word 'migrant'?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Marsh, David (28 August 2015). "We deride them as 'migrants'. Why not call them people?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Mudde, Cas (11 November 2019). The Far Right Today (1st ed.). Polity. p. 13. ISBN 978-1509536849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Asylum Statistics in the European Union: A Need for Numbers" (PDF). AIDA Legal Briefing. 2: 4. August 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Bitoulas, Alexander (2015), Asylum applicants and first instance decisions on asylum applications, Data in Focus, vol. 3/2015, Eurostat, archived from the original on 28 April 2023, retrieved 28 April 2023

- ^ "euronews – Data raises questions over EU's attitude towards asylum seekers". euronews.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Asylum in the EU" (PDF). European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b "UNHCR Global Trends –Forced Displacement in 2014". UNHCR. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ "The number of asylum applicants in the EU jumped to more than 625 000 in 2014". EUROSTAT. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Migrant boat capsizes off Libya, 400 feared dead". Fox News Channel. 15 April 2015. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ a b "EU Member States granted protection to more than 185 000 asylum seekers in 2014". EUROSTAT. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Silburn MPH FAWM, Alan; Tanvir, F.; Ton, J.; Lathigara, N.; Ashraf, R.; Arndell, J. (30 January 2024). "Ungoverned, Unfair, Unacceptable: A UN Solution to Refugee Distribution". International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis. 07 (1). doi:10.47191/ijmra/v7-i01-36. ISSN 2643-9840.

- ^ "Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Over one million sea arrivals reach Europe in 2015". UNHCR. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Refugee crisis: apart from Syrians, who is travelling to Europe?". The Guardian. 10 September 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "It's not at war, but up to 3% of its people have fled. What is going on in Eritrea?". The Guardian. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015. Archived 13 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine (44/2016) 4. March 2016; 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2016 (46/2017) 16. March 2017

- ^ "Burimi: Rezultatet e Anketë së Fuqisë Punëtore në Kosovë 2013". Kosovo Agency of Statistics, KAS/AKS. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "Sa është kosto e emigrantëve që po lëshojnë Kosovën dhe cila është mundësia parandalimit të emigrimit". Zëri. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ Frontex (2018). "Risk Analysis for 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Kosovo helpless to stem exodus of illegal migrants". Reuters. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Tan, Kim Hua; Perudin, Alirupendi (April 2019). "The "Geopolitical" Factor in the Syrian Civil War: A Corpus-Based Thematic Analysis". SAGE Open. 9 (2): 215824401985672. doi:10.1177/2158244019856729. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 197715781.

- ^ "Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response". data2.unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Mona, Chalabi (25 July 2013). "Syrian refugees: how many are there and where are they?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "Afghanistan: What you need to know about one of the world's longest refugee crises". International Rescue Committee (IRC). 8 September 2016. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Nigeria's Boko Haram attacks in numbers – as lethal as ever". BBC News. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Arrivals to Greece, Italy and Spain. January–December 2015" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Miles, Tom (22 December 2015). "EU gets one million migrants in 2015, smugglers seen making $1 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Why is EU struggling with migrants and asylum?". BBC News. 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Irregular Migrant, Refugee Arrivals in Europe Top One Million in 2015: IOM". IOM. 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Risk Analysis for 2016" (PDF). Frontex. March 2016. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Risk Analysis for 2016" (PDF). Frontex. March 2016. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Ledwith, Sara; Baczynska, Gabriela (4 April 2016). "How Europe built fences to keep people out". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Refugees and migrants outnumber Kastelorizo's residents". Protothema. 20 February 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (27 September 2015). "The Syrian refugee crisis, explained in one map". Vox. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "Migrant 'chaos' on Greek islands – UN refugee agency". BBC News. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (7 August 2015). "Greek Government Holds Emergency Meeting Over Soaring Migrant Arrivals". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: Croatia mines warning after border crossing". BBC News. 16 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Statistiche immigrazione". Italian Ministry of the Interior. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b Szymański, Piotr; Żochowski, Piotr; Rodkiewicz, Witold (6 April 2016). "Enforced cooperation: the Finnish-Russian migration crisis". Centre for Eastern Studies. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Pancevsky, Bojan (4 September 2016). "Norway builds Arctic border fence as it gives migrants the cold shoulder". The Times of London. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Osborne, Samuel (25 August 2016). "Norway to build border fence with Russia to keep out refugees". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022.

- ^ Hovland, Kjetil Malkenes (3 September 2015). "Syrian Refugees Take Arctic Route to Europe More than 150 refugees have entered Norway from Arctic Russia this year". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Norway Will Build a Fence at Its Arctic Border With Russia". The New York Times. Reuters. 24 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Roos, Dave (25 January 2019). "Norway's Ridiculously Short Border Fence". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ de Carbonnel, Alissa (20 November 2015). "A (Very) Cold War on the Russia-Norway Border". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Russian border guard to STT: Russian security service behind northeast asylum traffic". YLE. 24 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Burris, Scott (12 September 2015). "Why Do Refugees Risk the Deadly Boat Crossing to Europe? It's the Law". Bill of Health. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ a b Jones, Gavin (17 August 2017). "More NGOs follow MSF in suspending Mediterranean migrant rescues". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Yeginsu, Ceylan (16 August 2015). "Amid Perilous Mediterranean Crossings, Migrants Find a Relatively Easy Path to Greece". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Purtill, Corinne (25 September 2015). "This airline wants to safely fly refugees into Europe. Here's why it needs to exist". Quartz. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Refugee crisis: Smugglers offer 'bad weather discount' to migrants willing to make winter Mediterranean crossing". International Business Times UK. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "Europe's Refugee Crisis". Human Rights Watch. 16 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Carmichael, Lachlan. "EU tracking 65,000 migrant smugglers: Europol". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "40 migrants 'killed by fumes' in hold of boat off Libya". Irish Independent. 15 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "The Mediterranean's deadly migrant routes". BBC News. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.