This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

Rotation in mathematics is a concept originating in geometry. Any rotation is a motion of a certain space that preserves at least one point. It can describe, for example, the motion of a rigid body around a fixed point. Rotation can have a sign (as in the sign of an angle): a clockwise rotation is a negative magnitude so a counterclockwise turn has a positive magnitude. A rotation is different from other types of motions: translations, which have no fixed points, and (hyperplane) reflections, each of them having an entire (n − 1)-dimensional flat of fixed points in a n-dimensional space.

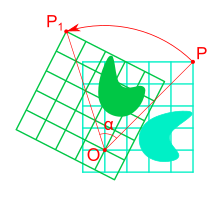

Mathematically, a rotation is a map. All rotations about a fixed point form a group under composition called the rotation group (of a particular space). But in mechanics and, more generally, in physics, this concept is frequently understood as a coordinate transformation (importantly, a transformation of an orthonormal basis), because for any motion of a body there is an inverse transformation which if applied to the frame of reference results in the body being at the same coordinates. For example, in two dimensions rotating a body clockwise about a point keeping the axes fixed is equivalent to rotating the axes counterclockwise about the same point while the body is kept fixed. These two types of rotation are called active and passive transformations.[1][2]

Related definitions and terminology

editThe rotation group is a Lie group of rotations about a fixed point. This (common) fixed point or center is called the center of rotation and is usually identified with the origin. The rotation group is a point stabilizer in a broader group of (orientation-preserving) motions.

For a particular rotation:

- The axis of rotation is a line of its fixed points. They exist only in n = 3.

- The plane of rotation is a plane that is invariant under the rotation. Unlike the axis, its points are not fixed themselves. The axis (where present) and the plane of a rotation are orthogonal.

A representation of rotations is a particular formalism, either algebraic or geometric, used to parametrize a rotation map. This meaning is somehow inverse to the meaning in the group theory.

Rotations of (affine) spaces of points and of respective vector spaces are not always clearly distinguished. The former are sometimes referred to as affine rotations (although the term is misleading), whereas the latter are vector rotations. See the article below for details.

Definitions and representations

editIn Euclidean geometry

editA motion of a Euclidean space is the same as its isometry: it leaves the distance between any two points unchanged after the transformation. But a (proper) rotation also has to preserve the orientation structure. The "improper rotation" term refers to isometries that reverse (flip) the orientation. In the language of group theory the distinction is expressed as direct vs indirect isometries in the Euclidean group, where the former comprise the identity component. Any direct Euclidean motion can be represented as a composition of a rotation about the fixed point and a translation.

In one-dimensional space, there are only trivial rotations. In two dimensions, only a single angle is needed to specify a rotation about the origin – the angle of rotation that specifies an element of the circle group (also known as U(1)). The rotation is acting to rotate an object counterclockwise through an angle θ about the origin; see below for details. Composition of rotations sums their angles modulo 1 turn, which implies that all two-dimensional rotations about the same point commute. Rotations about different points, in general, do not commute. Any two-dimensional direct motion is either a translation or a rotation; see Euclidean plane isometry for details.

Rotations in three-dimensional space differ from those in two dimensions in a number of important ways. Rotations in three dimensions are generally not commutative, so the order in which rotations are applied is important even about the same point. Also, unlike the two-dimensional case, a three-dimensional direct motion, in general position, is not a rotation but a screw operation. Rotations about the origin have three degrees of freedom (see rotation formalisms in three dimensions for details), the same as the number of dimensions. A three-dimensional rotation can be specified in a number of ways. The most usual methods are:

- Euler angles (pictured at the left). Any rotation about the origin can be represented as the composition of three rotations defined as the motion obtained by changing one of the Euler angles while leaving the other two constant. They constitute a mixed axes of rotation system because angles are measured with respect to a mix of different reference frames, rather than a single frame that is purely external or purely intrinsic. Specifically, the first angle moves the line of nodes around the external axis z, the second rotates around the line of nodes and the third is an intrinsic rotation (a spin) around an axis fixed in the body that moves. Euler angles are typically denoted as α, β, γ, or φ, θ, ψ. This presentation is convenient only for rotations about a fixed point.

- Axis–angle representation (pictured at the right) specifies an angle with the axis about which the rotation takes place. It can be easily visualised. There are two variants to represent it:

- as a pair consisting of the angle and a unit vector for the axis, or

- as a Euclidean vector obtained by multiplying the angle with this unit vector, called the rotation vector (although, strictly speaking, it is a pseudovector).

- Matrices, versors (quaternions), and other algebraic things: see the section Linear and Multilinear Algebra Formalism for details.

A general rotation in four dimensions has only one fixed point, the centre of rotation, and no axis of rotation; see rotations in 4-dimensional Euclidean space for details. Instead the rotation has two mutually orthogonal planes of rotation, each of which is fixed in the sense that points in each plane stay within the planes. The rotation has two angles of rotation, one for each plane of rotation, through which points in the planes rotate. If these are ω1 and ω2 then all points not in the planes rotate through an angle between ω1 and ω2. Rotations in four dimensions about a fixed point have six degrees of freedom. A four-dimensional direct motion in general position is a rotation about certain point (as in all even Euclidean dimensions), but screw operations exist also.

Linear and multilinear algebra formalism

editWhen one considers motions of the Euclidean space that preserve the origin, the distinction between points and vectors, important in pure mathematics, can be erased because there is a canonical one-to-one correspondence between points and position vectors. The same is true for geometries other than Euclidean, but whose space is an affine space with a supplementary structure; see an example below. Alternatively, the vector description of rotations can be understood as a parametrization of geometric rotations up to their composition with translations. In other words, one vector rotation presents many equivalent rotations about all points in the space.

A motion that preserves the origin is the same as a linear operator on vectors that preserves the same geometric structure but expressed in terms of vectors. For Euclidean vectors, this expression is their magnitude (Euclidean norm). In components, such operator is expressed with n × n orthogonal matrix that is multiplied to column vectors.

As it was already stated, a (proper) rotation is different from an arbitrary fixed-point motion in its preservation of the orientation of the vector space. Thus, the determinant of a rotation orthogonal matrix must be 1. The only other possibility for the determinant of an orthogonal matrix is −1, and this result means the transformation is a hyperplane reflection, a point reflection (for odd n), or another kind of improper rotation. Matrices of all proper rotations form the special orthogonal group.

Two dimensions

editIn two dimensions, to carry out a rotation using a matrix, the point (x, y) to be rotated counterclockwise is written as a column vector, then multiplied by a rotation matrix calculated from the angle θ:

- .

The coordinates of the point after rotation are x′, y′, and the formulae for x′ and y′ are

The vectors and have the same magnitude and are separated by an angle θ as expected.

Points on the R2 plane can be also presented as complex numbers: the point (x, y) in the plane is represented by the complex number

This can be rotated through an angle θ by multiplying it by eiθ, then expanding the product using Euler's formula as follows:

and equating real and imaginary parts gives the same result as a two-dimensional matrix:

Since complex numbers form a commutative ring, vector rotations in two dimensions are commutative, unlike in higher dimensions. They have only one degree of freedom, as such rotations are entirely determined by the angle of rotation.[3]

Three dimensions

editAs in two dimensions, a matrix can be used to rotate a point (x, y, z) to a point (x′, y′, z′). The matrix used is a 3×3 matrix,

This is multiplied by a vector representing the point to give the result

The set of all appropriate matrices together with the operation of matrix multiplication is the rotation group SO(3). The matrix A is a member of the three-dimensional special orthogonal group, SO(3), that is it is an orthogonal matrix with determinant 1. That it is an orthogonal matrix means that its rows are a set of orthogonal unit vectors (so they are an orthonormal basis) as are its columns, making it simple to spot and check if a matrix is a valid rotation matrix.

Above-mentioned Euler angles and axis–angle representations can be easily converted to a rotation matrix.

Another possibility to represent a rotation of three-dimensional Euclidean vectors are quaternions described below.

Quaternions

editUnit quaternions, or versors, are in some ways the least intuitive representation of three-dimensional rotations. They are not the three-dimensional instance of a general approach. They are more compact than matrices and easier to work with than all other methods, so are often preferred in real-world applications.[citation needed]

A versor (also called a rotation quaternion) consists of four real numbers, constrained so the norm of the quaternion is 1. This constraint limits the degrees of freedom of the quaternion to three, as required. Unlike matrices and complex numbers two multiplications are needed:

where q is the versor, q−1 is its inverse, and x is the vector treated as a quaternion with zero scalar part. The quaternion can be related to the rotation vector form of the axis angle rotation by the exponential map over the quaternions,

where v is the rotation vector treated as a quaternion.

A single multiplication by a versor, either left or right, is itself a rotation, but in four dimensions. Any four-dimensional rotation about the origin can be represented with two quaternion multiplications: one left and one right, by two different unit quaternions.

Further notes

editMore generally, coordinate rotations in any dimension are represented by orthogonal matrices. The set of all orthogonal matrices in n dimensions which describe proper rotations (determinant = +1), together with the operation of matrix multiplication, forms the special orthogonal group SO(n).

Matrices are often used for doing transformations, especially when a large number of points are being transformed, as they are a direct representation of the linear operator. Rotations represented in other ways are often converted to matrices before being used. They can be extended to represent rotations and transformations at the same time using homogeneous coordinates. Projective transformations are represented by 4×4 matrices. They are not rotation matrices, but a transformation that represents a Euclidean rotation has a 3×3 rotation matrix in the upper left corner.

The main disadvantage of matrices is that they are more expensive to calculate and do calculations with. Also in calculations where numerical instability is a concern matrices can be more prone to it, so calculations to restore orthonormality, which are expensive to do for matrices, need to be done more often.

More alternatives to the matrix formalism

editAs was demonstrated above, there exist three multilinear algebra rotation formalisms: one with U(1), or complex numbers, for two dimensions, and two others with versors, or quaternions, for three and four dimensions.

In general (even for vectors equipped with a non-Euclidean Minkowski quadratic form) the rotation of a vector space can be expressed as a bivector. This formalism is used in geometric algebra and, more generally, in the Clifford algebra representation of Lie groups.

In the case of a positive-definite Euclidean quadratic form, the double covering group of the isometry group is known as the Spin group, . It can be conveniently described in terms of a Clifford algebra. Unit quaternions give the group .

In non-Euclidean geometries

editIn spherical geometry, a direct motion[clarification needed] of the n-sphere (an example of the elliptic geometry) is the same as a rotation of (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space about the origin (SO(n + 1)). For odd n, most of these motions do not have fixed points on the n-sphere and, strictly speaking, are not rotations of the sphere; such motions are sometimes referred to as Clifford translations.[citation needed] Rotations about a fixed point in elliptic and hyperbolic geometries are not different from Euclidean ones.[clarification needed]

Affine geometry and projective geometry have not a distinct notion of rotation.

In relativity

editA generalization of a rotation applies in special relativity, where it can be considered to operate on a four-dimensional space, spacetime, spanned by three space dimensions and one of time. In special relativity, this space is called Minkowski space, and the four-dimensional rotations, called Lorentz transformations, have a physical interpretation. These transformations preserve a quadratic form called the spacetime interval.

If a rotation of Minkowski space is in a space-like plane, then this rotation is the same as a spatial rotation in Euclidean space. By contrast, a rotation in a plane spanned by a space-like dimension and a time-like dimension is a hyperbolic rotation, and if this plane contains the time axis of the reference frame, is called a "Lorentz boost". These transformations demonstrate the pseudo-Euclidean nature of the Minkowski space. Hyperbolic rotations are sometimes described as "squeeze mappings" and frequently appear on Minkowski diagrams that visualize (1 + 1)-dimensional pseudo-Euclidean geometry on planar drawings. The study of relativity deals with the Lorentz group generated by the space rotations and hyperbolic rotations.[4]

Whereas SO(3) rotations, in physics and astronomy, correspond to rotations of celestial sphere as a 2-sphere in the Euclidean 3-space, Lorentz transformations from SO(3;1)+ induce conformal transformations of the celestial sphere. It is a broader class of the sphere transformations known as Möbius transformations.

Discrete rotations

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2014) |

Importance

editRotations define important classes of symmetry: rotational symmetry is an invariance with respect to a particular rotation. The circular symmetry is an invariance with respect to all rotation about the fixed axis.

As was stated above, Euclidean rotations are applied to rigid body dynamics. Moreover, most of mathematical formalism in physics (such as the vector calculus) is rotation-invariant; see rotation for more physical aspects. Euclidean rotations and, more generally, Lorentz symmetry described above are thought to be symmetry laws of nature. In contrast, the reflectional symmetry is not a precise symmetry law of nature.

Generalizations

editThe complex-valued matrices analogous to real orthogonal matrices are the unitary matrices , which represent rotations in complex space. The set of all unitary matrices in a given dimension n forms a unitary group of degree n; and its subgroup representing proper rotations (those that preserve the orientation of space) is the special unitary group of degree n. These complex rotations are important in the context of spinors. The elements of are used to parametrize three-dimensional Euclidean rotations (see above), as well as respective transformations of the spin (see representation theory of SU(2)).

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2014) |

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Alibi Transformation." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Alias Transformation." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Lounesto 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Hestenes 1999, pp. 580–588.

References

edit- Hestenes, David (1999). New Foundations for Classical Mechanics. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-5514-8.

- Lounesto, Pertti (2001). Clifford algebras and spinors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00551-7.

- Brannon, Rebecca M. (2002). "A review of useful theorems involving proper orthogonal matrices referenced to three-dimensional physical space" (PDF). Albuquerque: Sandia National Laboratories.