Streetcars in Washington, D.C. transported people across the city and region from 1862 until 1962.

| Streetcars in Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|

A Washington, D.C., street car, c. 1890 | |

| Overview | |

| Transit type | Streetcar |

| Number of lines | in 1946: 17 in 1958: 15 |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | July 29, 1862 (horsecars) October 17, 1888 (electric) |

| Ended operation | ? (horsecars) January 28, 1962 (electric) |

| Operator(s) | Capital Transit Company |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrification | 600 volt DC conduit/overhead current collection |

The first streetcars in Washington, D.C., were horse-drawn and carried people short distances on flat terrain. After brief experiments with cable cars, the late-19th-century introduction of electric streetcars opened development of the hilly terrain north of the old city and in Anacostia into streetcar suburbs. The extension of several of the lines into Maryland and of two Virginia lines across the Potomac River into the District helped expand the city's dense downtown core into today's Washington metropolitan area.

By 1901, a series of mergers dubbed the "Great Streetcar Consolidation" had gathered most local transit firms into two major companies: Capital Traction Company and Washington Railway and Electric Company. In 1933, a second consolidation brought all streetcars under one company, Capital Transit.

Over the next decades, the streetcar system shrank amid the growing usage of the automobile and pressure to switch to buses. After a strike in 1955, the company changed ownership and became D.C. Transit, with explicit instructions to switch to buses. The system was dismantled in the early 1960s; the last streetcar ran on January 28, 1962.

Today, some streetcars, car barns, trackage, stations, and rights-of-way exist in various states of usage. In the Georgetown neighborhood, remnants of tracks and conduit remain visible in the middle of O and P Streets NW between 33rd and 35th Streets NW, and near an M Street door of the Georgetown Car Barn.

History

editEarly transit in Washington

editPublic transportation began in Washington, D.C., almost as soon as the city was founded. In May 1800, two-horse stage coaches began running twice daily from Bridge and High Streets NW (now Wisconsin Avenue and M Street NW) in Georgetown by way of M Street NW and Pennsylvania Avenue NW/SE to William Tunnicliff's Tavern at the site now occupied by the Supreme Court Building. Service ended soon after it began.[1]

The next attempt at public transit arrived in the spring of 1830, when Gilbert Vanderwerken's Omnibuses, horse-drawn wagons, began running from Georgetown to the Navy Yard. The company maintained stables on M Street, NW. These lines were later extended down 11th Street SE to the waterfront and up 7th Street NW to L Street NW. Vanderwerken's success attracted competitors, who added new lines, but by 1854, all omnibuses had come under the control of two companies, "The Union Line" and "The Citizen's Line." In 1860, these two merged under the control of Vanderwerken and continued to operate until they were run out of business by the next new technology: streetcars.[1][2]

Horse-drawn streetcars

editWashington and Georgetown Railroad

editStreetcars began operation in New York City along the Bowery in 1832,[3] but the technology did not really become popular until 1852, when Alphonse Loubat invented a side-bearing rail that could be laid flush with the street surface, allowing the first horse-drawn streetcar lines.[4] The technology began to spread and on May 17, 1862, the first Washington, D.C., streetcar company, the Washington and Georgetown Railroad was incorporated.[5] The company ran the first streetcar in Washington, D.C., from the Capitol to the State Department (then housed at the current Treasury Building) starting on July 29, 1862. It expanded to full operations from the Navy Yard to Georgetown on October 2, 1862.[1][6] Another line opened on November 15, 1862. It was built along 7th Street NW from N Street NW to the Potomac River and expanded to the Arsenal (now Fort McNair) in 1875.[7] A third line ran down 14th Street NW from Boundary Street NW (now Florida Avenue) to the Treasury Building. In 1863 the 7th Street line was extended north to Boundary Street NW.[2]

Metropolitan Railroad

editThe Washington and Georgetown's monopoly didn't last long. On July 1, 1864, a second streetcar company, the Metropolitan Railroad, was incorporated. It opened lines from the Capitol to the War Department along H Street NW.

In 1872, the railroad built a line on 9th Street NW and purchased the Union Railroad (chartered on January 19, 1872).[1] It used the Union's charter to expand into Georgetown. In 1873, it purchased the Boundary and Silver Spring Railway (chartered on January 19, 1872) and used its charter to build north on what is now Georgia Avenue.[8] In June 1874, it absorbed the Connecticut Avenue and Park Railway (chartered on July 13, 1868; operations started in April 1873) and its line on Connecticut Avenue from the White House to Boundary Avenue.[9] By 1888, it had built additional lines down 4th Street NW/SW to P Street SW, and on East Capitol Street to 9th Street.[1]

Columbia Railway

editChartered by Congress on May 24, 1870[10] and beginning operations the same year,[2] the Columbia Railway was the city's third horse car operator. It ran from the Treasury Building along H Street NW/NE to the city boundary at 15th Street NE. The company built a car barn and stable on the east side of 15th Street just south of H Street at the eastern end of the line.[11]

Anacostia and Potomac River Railroad

editThe Anacostia and Potomac River Railroad was chartered on May 5, 1870. It wasn't given approval by Congress until February 18, 1875, but it was constructed that year.[12] The streetcars traveled from the Arsenal and crossed the Navy Yard Bridge to Uniontown (now Historic Anacostia) to Nichols Avenue SE (now Martin Luther King Avenue) and V Street SE where a car barn and stables were maintained by the company.[13] In 1888 the Anacostia and Potomac River expanded from the Navy Yard to Congressional Cemetery, and past Garfield Park to the Center Market (now the National Archives) in downtown. It also expanded up Nichols Avenue past the Government Hospital for the Insane (now St. Elizabeths Hospital).[10]

Capitol, North O Street and South Washington Railway

editThe last streetcar company to begin operation during the horsecar era was the Capitol, North O Street and South Washington Railway. It was incorporated on March 3, 1875, and began operation later that year. It ran on a circular route around downtown D.C. A track on P Street NW was added in 1876. In 1881, the route was extended north and south on 11th Street West and tracks were rerouted across the Mall. It changed its name to the Belt Railway on February 18, 1893.[1][2][10]

Horse-drawn chariots and the Herdic Phaeton Company

editDuring this time, streetcars competed with numerous horse-drawn chariot companies. Starting on March 5, 1877, the date of President Hayes' inauguration, single-horse carriages began running on a route roughly parallel to the Washington and Georgetown's Pennsylvania Avenue route. After three years, streetcars forced the chariots out of business.

This was followed almost immediately by the Herdic Phaeton Company. The electric streetcar, however, was too much for the company to compete with and when its principal stockholder died in 1896, it ceased operations.[1]

After the Herdic Company went under, the Metropolitan Coach Company began running horse-drawn coaches in conjunction with the Metropolitan Railroad, carrying passengers from 16th and T Streets NW to 22nd and G Streets NW. It began operations on May 1, 1897, with a car barn at 1914 E Street NW. In 1904, it became its own corporation.[1]

The switch to electric power

editHorsecars, though an improvement over horse-drawn wagons, were slow, dirty and inefficient. Horses needed to be housed and fed, created large amounts of waste, had difficulty climbing hills and were difficult to dispose of. Early horsecar companies soon began looking for alternative means of motive power. For example, the Washington and Georgetown experimented with a steam motor car in the 1870s and 1880s which was run on Pennsylvania Avenue NW near the Capitol several times, but was never placed in permanent use.[1]

On February 2, 1888, the first successful electric streetcar system in the United States began to operate in Richmond, Virginia. The Richmond Union Passenger Railway was the result of five years of work by Frank Sprague, an 1878 Naval Academy graduate who had resigned his commission to work for Thomas Edison.[14] Richmond's example drew intense interest from many cities, including Washington.[3]

On March 2, 1889, the District's government authorized every streetcar company in Washington to switch from horse power to underground cable or to electricity provided by battery or underground wire. At least two D.C. streetcar companies would install cable mechanisms at great expense only to switch to electric power.

Others moved straight to electrically powered trolleys. But the editor of the Washington Star newspaper led a successful crusade against the use of overhead wires strung along streets to transmit electricity from steam-driven power stations to the streetcars themselves. Instead of this method, common in other cities but which the editor found aesthetically displeasing, D.C. would adopt a far more expensive and finicky system involving an electrical conduit laid between rails in the street.[15]

In 1890, the District authorized companies to sell stock to pay for the upgrades. In 1892, one-horse cars were banned within the city, and by 1894 Congress began requiring companies to switch to something other than horse power.[citation needed]

New electric streetcar companies

editBy 1888, Washington was expanding north of Boundary Street NW into the hills of Washington Heights and Petworth. Boundary Street was becoming such a misnomer that in 1890 it was renamed Florida Avenue.[citation needed] Climbing the hills to the new parts of the city was difficult for horses, but electric streetcars could do it easily. In the year following the successful demonstration of the Richmond streetcar, four electric streetcar companies were incorporated in Washington, D.C.[citation needed]

Eckington and Soldiers' Home

editThe Eckington and Soldiers' Home Railway was the first to charter, on June 19, 1888, and started operation on October 17. Its tracks started at 7th Street and New York Avenue NW, east of Mount Vernon Square, and traveled 2.5 miles to the Eckington Car Barn at 4th and T Streets NE via Boundary Street NE, Eckington Place NE, R Street NE, 3rd Street NE and T Street NE.[16]

Another line ran up 4th Street NE to Michigan Avenue NE. A one-week pass cost $1.25.[6] In 1889, the line was extended along T Street NE, 2nd Street NE and V Street NE to Glenwood Cemetery, but the extension proved unprofitable and was closed in 1894.[17]

At the same time, an extension was built along Michigan Avenue NE to the B&O railroad tracks. In 1895, the company removed its overhead trolley lines in accordance with its charter and attempted to replace them with batteries. These proved too costly and the company replaced them with horses in the central city.[1]

In 1896, Congress directed the Eckington and Soldier's Home to try compressed air motors and to substitute underground electric power for all its horse and overhead trolley lines in the city.[10] The compressed-air motors were a failure; three years later, the company would switch to standard underground electric power conduit.[1]

Rock Creek Railway

editThe Rock Creek Railway, the second electric streetcar company incorporated in D.C., was incorporated in 1888 and started operations in 1890 on two blocks of Florida Avenue east of Connecticut Avenue.[10] After completing a bridge over Rock Creek at Calvert Street on July 21, 1891, the line was extended through Adams Morgan and north on Connecticut Avenue to Chevy Chase Lake in Maryland.[1] In 1893, a line was added through Cardozo/Shaw to 7th Street NW.[9]

Georgetown and Tenleytown

editA trio of streetcar companies provided service from Georgetown north and ultimately to Rockville, Maryland. The first one was the Georgetown and Tennallytown Railway, chartered on August 22, 1888, and just the third D.C. streetcar company to incorporate.[10] It began operations in 1890 on a route that ran up from M Street NW up 32nd Street NW[18] and then onto the Georgetown and Rockville Road (now Wisconsin Avenue NW) to the extant village of Tenleytown. That same year,[19] the Tennallytown and Rockville Railway received its charter and began building tracks from the G&T's northern terminus to today's D.C. neighborhood of Friendship Heights and the Maryland state line.[20] Finally, the Washington and Rockville Electric Railway was incorporated in 1897[19] to extend the tracks into Maryland line and onward to Bethesda and Rockville.[21] Controlling interest in the companies was obtained first by the Washington Traction and Electric Company, then in 1902 by the Washington Railway and Electric Company. Streetcar service was replaced with buses in 1935.

Washington and Great Falls - Maryland and Washington

editTwo more Washington, D.C., streetcar companies operating in Maryland were incorporated by acts of Congress in the summer of 1892. Congress approved the Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway Company's charter on July 28, 1892, permitting the company to build an electric streetcar line from Georgetown to Cabin John, Maryland. Its tracks reached the District–Maryland line on September 28, 1895 and Cabin John in 1897.[22]

Congress approved the Maryland and Washington Railway's charter on August 1, 1892. That railroad's tracks ran on Rhode Island Avenue NE from 4th Street NE reaching what is now Mount Rainier on the Maryland line in 1897.[23] At its southern terminus it connected to the Eckington and Soldier's Home.[1]

Capital Railway

editThe first electric streetcar to operate in Anacostia was the Capital Railway. It was incorporated by Colonel Arthur Emmett Randle on March 2, 1895, to serve Congress Heights. It was to run from Shepherds Ferry along the Potomac and across the Navy Yard Bridge to M Street SE.

A second line would run along Good Hope Road SE to the District boundary.[10] The line was built during the Panic of 1896 despite 18 months of opposition from the Anacostia and Potomac River.[24] In 1897 it experimented with the "Brown System", which used magnets in boxes to relay power instead of overhead or underground lines, and with double trolley lines over the Navy Yard Bridge. Both were failures.[1]

By 1898, the streetcar line ran along Nichols Avenue SE to Congress Heights, ending at Upsal Street SE.[13] At the same time the Capital Railway was incorporated, the Washington and Marlboro Electric Railway was chartered to run trains across the Anacostia River through southeast Anacostia to the District boundary at Suitland Road and from there to Upper Marlboro, but it never laid any track.[10]

Baltimore and Washington

editThe Baltimore and Washington Transit Company was incorporated before 1894, with authorization to run from the District of Columbia across Maryland to the Pennsylvania border.[25] On June 8, 1896, it was given permission to enter the District of Columbia and connect to the spur of the Brightwood line that ran on Butternut St NW.[1][10] In 1897, the railroad began construction on a line, known locally as the Dinky Line, that began at the end of the Brightwood spur at 4th and Butternut Streets NW, traveled south on 4th Street NW to Aspen Street NW and then east on Aspen Street NW and Laurel Street NW into Maryland.[26]

Between 1903 and 1917, a line was added running south on 3rd St NW and west on Kennedy St NW to Colorado Avenue where it connected to Capital Traction's 14th Street line. On March 14, 1914, it changed its name to the Washington and Maryland Railway.[1]

East Washington Heights

editThe East Washington Heights Traction Railroad was incorporated on June 18, 1898.[1] By 1903 it ran from the Capitol along Pennsylvania Avenue SE to Barney Circle, and by 1908, it went across the bridge to Randle Highlands (now known as Twining) as far as 27th St SE.[27][28][29] By 1917 it had been extended out Pennsylvania Avenue past 33rd Street SE.,[30] but the company ceased operations by 1923.[31]

Washington, Spa Spring, and Gretta

editOn July 5, 1892, the District of Columbia Suburban Railway was incorporated to run streetcars on Bladensburg Road NE from the Columbia Railroad tracks on H Street NE to the Maryland line and from Brookland to Florida Avenue NE.[32] It was never built.

But the route was reused by the final streetcar company to form in D.C.: the Washington, Spa Spring and Gretta Railroad. It was chartered by the state of Maryland on February 13, 1905, and authorized to enter the District on February 18, 1907.[1] Construction began by March 22, 1908.[33]

In 1910, the company began running cars along a single track from a modest waiting station and car barn near 15th Street NE and H Street NE along Bladensburg Road NE to Bladensburg.

Although initially planned to go as far as Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the line never ran further than an extension to Berwyn Heights, Maryland. The route was planned to promote development of company-owned land adjacent to the tracks, but it never successfully competed with established rail lines in the same area.[11] Noting its diminished ambitions, it became the Washington Interurban Railway on October 12, 1912,[1] and changed the Railway to Railroad in 1919.

Washington and Georgetown Railroad

editAfter the March 2, 1889, D.C. law passed, the Washington and Georgetown began installing an underground cable system. Their 7th Street line switched to cable car on April 12, 1890. The rest of the system switched to cable by August 18, 1892.[1][2] In 1892, they extended their track along 14th to Park Road NW.

Brightwood Railway Company

editOn October 18, 1888,[34] the day after the Eckington and Soldier's Home began operation, Congress authorized the Brightwood Railway Company to electrify the Metropolitan's streetcar line on Seventh Street Extended NW or Brightwood Avenue NW (now known as Georgia Avenue NW) and to extend it to the District boundary at Silver Spring. In 1890, they bought the former Boundary and Silver Spring line from the Metropolitan, but continued to operate it as a horse line. In 1892 it was ordered by Congress to switch to overhead electrical power and complete the line.[10][8] The next year, the streetcar tracks reached Takoma Park via a spur along Butternut Street NW to 4th Street NW.[35] In 1898, the Brightwood was ordered to switch to underground electric power on pain of having its charter revoked.[36]

Metropolitan

editThe Metropolitan experimented with batteries in 1890 but found them unsatisfactory. On August 2, 1894, Congress ordered the Metropolitan to switch to underground electrical power. It complied, installing the underground sliding shoe on the north–south line in January 1895.[1] The Metropolitan switched the rest of the system to electric power on July 7, 1896.[1] In 1895, the Metropolitan built a streetcar barn near the Arsenal and a loop in Georgetown to connect it to the Georgetown Car Barn.[1] In 1896, it extended service along East Capitol Street and built the East Capitol Street Car Barn.[37] It also extended its service from Connecticut Avenue to Mount Pleasant, running up Columbia Avenue and Mount Pleasant Road to Park Road.[9]

Columbia

editThe Columbia decided to try a cable system, the last cable car system built in the United States. They built a new cable car barn and began operating the system on March 9, 1895. It became clear that the underground electrical system was superior, so it quickly abandoned cable cars and switched to electrical power on July 22, 1899. The last cable car in the city ran the next day.[1]

Using electricity from the power plant built to power its cable operation, the Columbia won permission in 1898 to build a line east along Benning Road NE, splitting on the east side of the Anacostia. One branch ran to Kenilworth, and the other, built in 1900, connected at Seat Pleasant with the terminus of the steam-powered Chesapeake Beach Railway.[11]

Belt

editIn 1896, the Belt Railway tried out compressed air motors.[10] The compressed air motors were a failure, and in 1899 the cars were equipped with the standard underground power system.[1]

Anacostia and Potomac River

editThe Anacostia and Potomac River switched from horses to electricity in April 1900.[1][38] This was the last horse-drawn streetcar to run in the District.[1]

Virginia trolleys operating in Washington, D.C.

editTwo electric trolley companies serving Northern Virginia also operated in the District; a third received permission to do so, but never did.

The Washington & Arlington Railway was the first Virginia company given permission to operate in Washington. It was incorporated on February 28, 1892, with the right to run a streetcar from the train station at 6th Street NW and B Street NW to Virginia across a planned new Three Sisters Bridge.[10] It was also allotted space in the Georgetown Car Barn.[39] The company was never able to build the new bridge, and so never operated in Washington.

The Washington, Alexandria, and Mount Vernon Electric Railway began operating between Alexandria and Mount Vernon in 1892. On August 23, 1894, it was given permission to enter the District of Columbia using a boat or barge. However, the railroad never actually used any such watercraft.[40]

The railroad completed its tracks in 1896 and began serving a waiting station at 14th Street NW and B Street NW. From the waiting station it used the Belt Line Street Railway Company's tracks on 14th Street NW to reach the Long Bridge, a combined road and rail crossing of the Potomac River.[40] In 1906, the Long Bridge's road and streetcar tracks were relocated to a new truss bridge (the Highway Bridge), immediately west of the older bridge.[40][41] This span was removed in 1967.[42]

In 1902, the railroad moved its station, as the Belt Line's tracks were circling the block containing the site of a planned new District Building (now the John A. Wilson Building). The new station at 1204 N. Pennsylvania Avenue extended along 12th Street NW from Pennsylvania Avenue NW to D Street NW, near the site of the present Federal Triangle Metro station and on the opposite side of 12th Street from the Post Office building.[40][43]

On October 17, 1910, the Washington and Arlington, by then the Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railroad, and the Washington, Alexandria and Mount Vernon merged to form the Washington–Virginia Railway.[1] The company had difficulty competing and in 1924 declared bankruptcy. In 1927 the two companies were split and sold at auction.[44] The former Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railroad reemerged as the Arlington and Fairfax Railway[44] and continued to serve the city on the Washington-Virginia route until January 17, 1932, when the Mt. Vernon Memorial Highway (now the George Washington Memorial Parkway) opened.[42]

The Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad was chartered on January 24, 1900, and authorized to enter the District on January 29, 1903. It crossed over the Aqueduct Bridge and terminated at a station immediately west of the Georgetown Car Barn.[1] In 1912, it was incorporated into the new Washington and Old Dominion Railway and became the Great Falls Division of that company.

The Great Streetcar Consolidation

editBy the mid-1890s, there were numerous streetcar companies operating in the city. Congress attempted to deal with this fractured transit system by requiring them to accept transfers, set standard pricing and by allowing them to use one another's track. But eventually, lawmakers settled on consolidation as the best solution.

On March 1, 1895, Congress authorized the Rock Creek to purchase the Washington and Georgetown on September 21, producing the Capital Traction Company.[45] The consolidated company would replace its cable cars with an electric system after its powerhouse at 14th and E NW burned down in 1897. The various branches switched to electric power by the end of 1898.[1]

In 1898, the Eckington and Soldier's Home purchased the Maryland and Washington Railway and the Mount Rainier-to-Laurel Columbia and Maryland Railway; it changed its name to the City and Suburban Railway of Washington.[1]

Also that year, the Anacostia and Potomac River began expanding by purchasing the Belt Railway; the next year, it bought the Capital Railway.

Between 1896 and 1899, a consortium of three businessmen purchased controlling interests in several regional streetcar companies: the Metropolitan; the Columbia; the Anacostia and Potomac River; the Georgetown and Tennallytown; the Washington, Woodside and Forest Glen; the Washington and Great Falls; and the Washington and Rockville railway companies. This consortium also gained control of the Potomac Electric Power Company and the United States Electric Lighting Company. They incorporated the Washington Traction and Electric Company on June 5, 1899, as a holding company for these interests. But the holding company had borrowed too heavily and paid too much for the subsidiaries and quickly landed in financial trouble.

To prevent transit disruption, in 1900 Congress authorized the Washington and Great Falls to acquire the stock of any and all of the railways and power companies owned by Washington Traction, which defaulted on its loans a year later. Washington and Great Falls moved in to take its place in 1902 and changed its name to the Washington Railway and Electric Company (WR&E), reincorporated as a holding company and exchanged stock in Washington Traction and Electric one for one for stock in the new company (at a discounted rate).[36]

Not every company became a part of the WR&E immediately. The City and Suburban Railway[46] and the Georgetown and Tennallytown operated as subsidiaries of the WR&E until 1926, when it purchased the remainder of their stock.[36]

During this time, the streetcar companies continued to expand both trackage and service. The American Sight-Seeing Car and Coach Company started running tourist cars along the WR&E streetcar tracks in 1902 and continued until it switched to large automobiles in 1904.[1] In 1908, the WR&E's U Street line was extended east down Florida Avenue NW/NE to 8th Street NE, and from there south down 8th Street NE/SE to the Navy Yard.[11] Streetcars began serving to Union Station along Delaware Avenue NE in mid-1908, and cars of both Capital Traction and the WR&E were serving the building along Massachusetts Avenue NE by year's end.[47]

In 1908, the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway began service from Washington to Baltimore and Annapolis. Though technically an interurban, this railway used streetcar tracks from its terminal at 15th and H Streets NE and across the Benning Road Bridge where it switched to its own tracks in Deanwood. It was the main source of transportation to Suburban Gardens, known as "the black Glen Echo", the first and only major amusement park within Washington.[11]

The next major consolidation occurred in 1912, when the WR&E purchased the controlling stock of the Anacostia and Potomac River. This left six companies operating in Washington, four of which had less than 3 miles of track.[1] It also led to Congress passing the "Anti-Merger Act", prohibiting mergers without Congress' approval and establishing the Public Utilities Commission. In 1914 a failed attempt was made to have the federal government purchase all of the streetcar lines and companies.[1] Streetcars were unionized in 1916 when local 689 of the Amalgamated Association of Street, Electric Railway and Motor Coach Employees of America won recognition after a three-day strike.[48]

In 1916, Capital Traction took ownership of the Washington and Maryland and its 2.591 miles of track.[36]

Further consolidation came in the form of the North American Company, a transit and public utility holding company. North American began to acquire WR&E stock in 1922, gaining a controlling interest by 1928. By December 31, 1933, it owned 50.016% of the voting stock. North American tried to purchase Capital Traction, but never owned more than 2.5% of Capital Traction stock.[36]

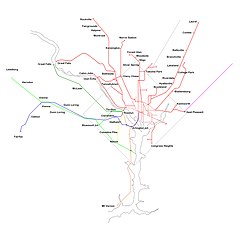

Bustitution and competition

editBy 1916, streetcar use was reaching its peak in Washington, D.C. The combined systems had over 200 miles of track,[6] with almost 100 in the city.[1] Passengers could travel to Great Falls, Glen Echo, Rockville, Kensington and Laurel in Maryland; and to Mount Vernon, Alexandria, Vienna, Fairfax, Leesburg, Great Falls and Bluemont in Virginia. World War I saw further increases in passenger traffic.[49] But the streetcars were also under increasing threat from competition.

The first threat to the streetcars was gasoline-powered taxicabs. The taximeter, invented in 1891, combined with the combustion engine, created a new form of public transportation. The first taxicabs hit Washington streets in 1908, and their numbers grew thereafter.[1][50]

Buses were the next competitors. In 1909, the Metropolitan Coach Company began to switch from horse-drawn coaches to gasoline-powered coaches. It had completed the transition by 1913, becoming a precursor to the bus companies. But it failed financially and on August 13, 1915, the company ceased operations.[1] The first formal bus company in the nation's capital, the Washington Rapid Transit Company, was incorporated in 1921. By 1932, it was carrying 4.5% of transit customers.[36] Two years later, the last streetcar line was built.[51]

In 1923, three streetcar companies switched to buses. The first was the East Washington Heights,[52] which replaced its two streetcars and one mile of track with a bus line.[28] The Washington Interurban switched next; its tracks were removed when Bladensburg Road was repaved.[11]

The same year, operations across the Potomac River between Rosslyn and Georgetown were handed over by the Washington and Old Dominion Railway, which had run on the decaying Aqueduct Bridge, to Capital Traction Company, running down the center of the new Key Bridge. The W&OD agreed not to vie for rights on the new bridge, and Capital Traction, which had been seeking cross-river operations, built a new terminal for the Virginia railroad next to its own new loop in Rosslyn.[53][54]

In 1931, Capital Traction abandoned the decades-old service of delivering freight aboard its streetcars.[49]

Nearly a decade after the W&OD left Washington, the Arlington and Fairfax lost the right to use the Highway Bridge.[55] The last Arlington and Fairfax streetcar departed from 12th Street NW and D Street NW, on January 17, 1932. The Arlington and Fairfax Motor Transportation Company was established to replace the streetcar service.[6]

In the summer of 1935, after the consolidation, Capital Transit converted several major lines from streetcars to buses: the line from Friendship Heights to Rockville (formerly the Washington and Rockville), the P Street line (Metropolitan), the Anacostia-Congress Heights line (Capital Railway) and the Connecticut Avenue line in Chevy Chase (Rock Creek). At the same time, the Chesapeake Beach Railway and the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis interurban ceased operations.[6]

The Columbia Railway Company Car Barn was converted to a bus barn in 1942.[56][57]

Monopoly

editThe WR&E, Capital Traction, and Washington Rapid Transit merged to form the Capital Transit Company in 1933. The WR&E continued as a holding company, owning 50% of Capital Transit and 100% of Potomac Electric Power Company (PEPCO), but Capital Traction was dissolved.[36] For the first time, street railways in Washington were under the management of one company.

Capital Transit made several changes. As part of the merger, the Capital Traction generating plant in Georgetown was closed (and, in 1943, decommissioned) and Capital Transit used only conventionally supplied electric power.[58] In 1935, it closed several lines and replaced them with bus service.

Because the Rockville line in Maryland was one of the lines that was closed, the Capital Transit Community Terminal was opened at Wisconsin Avenue NW and Western Avenue NW on August 4, 1935. At the same time, the car barn on the west side of Wisconsin at Ingomar was razed and replaced with the Western Bus Garage.[59]

In 1936, the system introduced route numbers.[2] On August 28, 1937, the first PCC streetcars began running on 14th Street NW. By early 1946, the company would place in service 489 of the streamlined, modern PCC model and, in the early 1950s, become the first in the nation to have an all-PCC fleet.[49][60]

During the 1930s, city newspapers began pushing for streetcar tunneling. The Capitol Subway was built in 1906 and three years later, the Washington Post called for a citywide subway to be built. Nothing happened until Capital Transit took over. The full $35 million plan to depress streets as trenches for exclusive streetcar use never materialized, but in 1942 an underground loop terminal was built at 14th and C Streets SW under the Bureau of Engraving and [61] on December 14, 1949, the Connecticut Avenue subway tunnel under Dupont Circle, running from N Street to R Street, was opened.[48]

At first, business was good for the new company. During World War II, gasoline rationing limited automobile use, but transit companies were exempt from the rationing. Meanwhile, wage freezes held labor costs in check. With increased revenue and steady costs, Capital Transit conservatively built up a $7 million cash reserve.[48] In 1945, Capital Transit had America's third-largest streetcar fleet.[51]

In 1946 in a decision by the United States Supreme Court in North American Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission,[62] the Supreme Court upheld the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 and forced North American, because it also owned the Potomac Electric Power Co., to sell its shares of Capital Transit. Buyers were hard to come by, but on September 12, 1949, Louis Wolfson and his three brothers purchased from North American 46.5% of the company's stock for $20 per share and the WR&E was dissolved.[63] For $2.2 million they bought a company with $7 million in cash.

The Wolfsons began paying themselves huge dividends until, in 1955, the war chest was down to $2.7 million. During the same period, transit trips dropped by 40,000 trips per day and automobile ownership doubled.[48]

Capital Transit lost one of its last freight customers in 1954 when the East Washington Railway took over the delivery of coal from the B&O to the PEPCO power plant at Benning. Previously this had been done using Capital Transit's steeple-cab electric locomotives operating over a remnant of the Benning car line.[6]

D.C. Transit

editIn January 1955 the Capital Transit Company, then consisting of 750 buses and 450 streetcars,[48] sought permission for a fare increase, but was denied. So that spring, when employees asked for a raise, there was no money available and the company refused to increase pay.

Frustrated, employees went on strike on July 1, 1955. The strike, only the third in D.C. history and the first since a three-day strike in 1945, lasted for seven weeks. Commuters were forced to hitch rides and walk in the brutal summer heat.[48]

On July 18, 1956, after Wolfson dared the Senate to revoke his franchise, claiming no other entrepreneur would take the company on, the 84th United States Congress did just that. On July 24, 1956, Public Law 84-757 (An Act to grant a franchise to D. C. Transit System, Inc., and for other purposes) was approved.[64] Soon afterwards, O. Roy Chalk, a New York financier, bought the franchise for $13.5 million (equivalent to $151 million in 2023)[48] and renamed it D.C. Transit.[65] Chalk controlled D.C. Transit through his controlling interest in Trans Caribbean Airways. According to 1959 Congressional Hearing testimony, Trans Caribbean owned 85% of the stock of D.C. Transit.[66] At that time, Trans Caribbean was a small scheduled carrier flying from New York to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

During the summer of 1970, D.C. Transit "came under fire from a group of its African American drivers for discrimination in promotions and assignments". There were specific complaints about a lack of black leadership.[67]

On January 3, 1971, Chalk appointed Robert W. Dickerson, Jr. as Superintendent of Operating Personnel.[67] The first black person to lead D.C. Transit, Dickerson had joined the company as a bus operator after completing college and serving in the U.S. Army. He then rose through the ranks from Depot Clerk to Acting Coordinator of Operating Personnel before being appointed to the leadership position.[67]

Abandonment

editAs part of the sale of Capital Transit to Chalk, Congress required him to replace all streetcars with buses by 1963.[48] Chalk fought the retirement of the streetcars[48] but was unsuccessful, and the final abandonment of the streetcar system began in 1958, with the end of the North Capitol Street (Route 80) and Maryland (Route 82) lines.[6] The Glen Echo (Route 20), Friendship Heights (Route 30) & Georgia Avenue (Routes 70, 72, 74) streetcar lines were abandoned at the start of 1960 and the Southern Division (Maine Avenue) Car Barn was closed.[2] This technically ended "trolley" cars in D.C. as only conduit operations remained.[6] The streetcar lines to Mount Pleasant (Routes 40, 42) and 11th Street (Route 60) were abandoned at the end of 1961.[68]

The remaining system, including lines to the Navy Yard, the Colorado Avenue terminal, and the Bureau of Engraving (Routes 50, 54) and to the Calvert Street Loop, Barney Circle, and Union Station (Routes 90, 92) was shut down in January 1962. Early on the morning of Sunday, January 28, 1962, preceded by cars 1101 and 1053, car 766 entered the Navy Yard Car Barn for the last time, and Washington's streetcars became history.[69] The last scheduled run, filled with enthusiasts and drunken college students, left 14th and Colorado at 2:17 am and arrived at Navy Yard ten minutes late at 3:05 am. One last special trip, carrying organized groups of trolley enthusiasts, set out after that and returned at 4:45 am. By the afternoon of the 28th, workers began tearing out the streetcar tracks and platforms along 14th Street.[70]

Remnants

editStreet cars

editAfter the system was abandoned, several hundred cars were cut in half at the center door and scrapped.[71] Others were sold: Barcelona's system bought 101 cars, some of which continued in service until 1971;[72] Sarajevo's ran 71 cars until 1983, including 9 that were converted to the only articulated PCC streetcars;[73] and Fort Worth, Texas, bought 15 to run on the Tandy Center Subway until it shut down in 2002.[74]

About 20 streetcars remain in existence, none in active daily operation. One Capital Transit PCC car has been restored and operates occasional special service in Sarajevo.[75] One of the trams sold to Fort Worth, Capital Transit 1551, was repainted and transferred to the McKinney heritage streetcar in Dallas in 2002, but has been out of service since 2006 with mechanical and electrical problems.

Others serve as museum pieces. The only Washington streetcar still in the District is Capital Traction 303, on display in the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.[76] The Smithsonian Institution also preserved Washington and Georgetown 212. The car is in storage at the Smithsonian's facility in Suitland, Maryland.[77]

Others are preserved, in various conditions, at the National Capital Trolley Museum in Colesville, Maryland, including D.C. Transit/Capital Transit 1101, 1430, and 1540; Capital Traction 522, 27 (ex-DC Transit 766) and 09; and WR&E 650.[78] Three more were destroyed in a fire on September 28, 2003.[79] In July 2020, the museum acquired DC Transit 1470 from the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke, Virginia.[80]

Farther from D.C., Capital Transit 010 (a snow sweeper) is in the collection of the Connecticut Trolley Museum.[81] D.C. Transit 1304 is at the Seashore Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport, Maine.[82]

Three of the Ft. Worth cars are held in storage by North Texas Historic Transportation with plans to place them in a yet-to-be-built museum.[83] One of the Tandy Center cars is preserved by Leonard's Museum.[84] Two of the Barcelona cars are privately owned and stored in Madrid, Spain and Ejea de los Caballeros, Spain.[85] Another two are in the Museu del Transport in Castellar de n'Hug, Spain.[86]

Tracks

editMuch of the track in Washington, D.C. was removed and sold for scrap. The complex trackwork on Capitol Plaza in front of Washington Union Station was removed in the mid-1960s. The Pennsylvania Avenue NW trackwork between the Capitol and the Treasury Building was removed during the street's mid-1980s redevelopment. Elsewhere, the track was buried under pavement.

The loop tracks of the former Capital Transit connection, behind the closed restaurant on Calvert Street NW, immediately east of the Duke Ellington Bridge, are extant under asphalt. The tracks on Florida Avenue also exist under pavement (as shown by the eternal seam above the conduit). Tracks also exist under Ellington Place NE, 3rd Street NE, 8th Street SE, and elsewhere. In 1977, the tracks on M Street and Pennsylvania Avenue in and near Georgetown were paved over.[87]

Visible remnants of the Metropolitan Railroad's Georgetown tracks and conduit remain intact in the centers of the cobblestoned blocks of O and P Streets NW between 33rd and 35th Streets NW.[88][89] Remnants of tracks and conduit also remain visible near an M Street door of the Georgetown Car Barn.[89][90]

Car barns and shops

editSome car barns, or car houses as they were later known, survived in part or in whole.

- The Washington and Georgetown Car Barn (later known as the M Street Shops) at 3222 M Street NW, which had served as stables for Gilbert Vanderwerken's omnibus line, a streetcar garage and maintenance shop and as a tobacco warehouse, was turned into a mall known as The Shops at Georgetown Park in 1981.[91] Only the facade of the original car barn remains.[28]

- The Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company Car Barn at 1346 Florida Avenue NW, originally built in 1877 and sold in 1892, is known today as the west building of the Manhattan Laundry. It served as the home to the Booker T. Washington Public Charter School from 1999 to 2014.[92] It's now home to the Franklin Hall bar, Maydan restaurant and La Colombe coffee.

- The original Eckington Car Barn at 400 T Street NE burned down before 1920 and a new one was built to replace it.[93] That building is now a postal vehicle maintenance facility.

- The Navy Yard Car Barn (officially the Washington and Georgetown Railroad Car House and colloquially "The Blue Castle") at 770 M Street SE is the sole surviving artifact of the cable car era. Its building has served as a bus garage and in 2021 was home to the Richard Wright Public Charter School.[94][95]

- In 2005, Preferred Real Estate Investments, Inc., bought the building and made plans to use it for retail space.[95] In January 2008, Madison Marquette Real Estate Services purchased the building, held it as an investment and used its space for offices.[96] In 2014, Madison Marquette sold the building to the National Community Church, which renovated it, renamed it to "The Capital Turnaround" and made plans to use its space for an indoor marketplace, a child development center and a 1000-seat event space where the church would conduct services.[96][97]

- The Georgetown Car Barn at 3600 M Street NW, with "Capital Traction Company" still written above the main door, now serves as classroom and administrative space for Georgetown University.[98] It includes the famous "Exorcist steps" that connect Prospect Street NW to M Street NW. O. Roy Chalk owned the building until 1992 when the Minneapolis-based Lutheran Brotherhood took possession of the property in a foreclosure. Developer Douglas Jemal bought it in May 1997.[99]

- The East Capitol Street Car Barn, at 1400 East Capitol Street NE, was used as a bus barn from 1962 to 1973 and then sat vacant until it was turned into condominiums.[37]

- The Decatur Street Car Barn (a.k.a. the Capital Traction Company Car Barn or Northern Carhouse), at 4615 14th Street NW, was built in 1906 and is now used as a Metrobus barn. One of three designed by Waddy Wood, it is the only car barn still used for transit.[100]

- Benning Car House, the red brick building at the northeast corner of Benning Road & Kenilworth Avenue on the grounds of PEPCO's Benning Road Power Plant, was built in 1941 and went out of service with the conversion of this carline to buses in 1949.[28] The building has been structurally modified and still stands.

- Grace Street Power House, at 3221 Grace Street. Built in 1917 by the D.C. Paper Manufacturing Company, the three-bay brick-and-steel structure was built to serve as the power house for the paper company. By 1919, the paper company was using a different power house and this one was purchased by the Capitol Traction Company, to use as a store room.

Other car barns were demolished.

- The Anacostia and Potomac River Car Barn at Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue SE and V Street SE is gone.

- The Columbia Railway Car Barn in Trinidad served as a bus barn until it was demolished in 1971 and replaced with apartments.[56]

- The Metropolitan Street Railway Car Barn (a.k.a. the Seventh Street-Wharves Barn) and the adjacent shops on 4th Street SW were torn down in 1962 to make room for the Riverside Condominiums.[101]

- The Tenleytown Car Barn (a.k.a. Western Carhouse or Tennally Town Car Barn), the first car barn and powerhouse for the Tennallytown line, was built around 1897 at what is now the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue NW and Calvert Street NW.[102] It was removed sometime before 1920[93] and replaced around 1935. This second structure was removed before 1958.[103]

- The Capital Traction Company Powerhouse in Georgetown was torn down in 1968; the land it sat on is now part of the Georgetown Waterfront Park.[104]

- Falls Barn, near Georgetown University, was demolished between 1948 and 1958.[103][105]

- A car barn was built in Mount Pleasant around 1892,[106] but it was gone by 1948.[105]

- A barn was built at 2411 P Street NW by the Metropolitan around 1870 and served as stables, a power house, car barn and repair shops. Much of the property was destroyed when Q Street was extended, but the remainder lasted until at least 1920.[93]

- The Brightwood Car House, at 5929 Georgia Avenue NW, was built in 1909 as a car barn and electric generation substation to replace a 'car stable' that burned down on January 16, 1898. It was designed by the engineer W.B. Upton who also designed the Eckington car barn. In 1955 PEPCO sold the car barn, and it ceased operation as a streetcar facility.

- The car barn became the showroom and service center for Hicks Chevrolet which modified the facade. In 1976 the dealership was sold and became Curtis Chevrolet.[107] Curtis Chevrolet closed on November 30, 2007, and was sold to Foulger-Pratt for redevelopment.[108] Though the D.C. Historical Preservation Society asked Foulger-Pratt to reuse, not destroy, the car house,[109] in 2010, Walmart announced that they planned to raze the car barn and build a store on the site, to open in 2012.[110]

- Plans by Walmart to bring the entire structure down were approved and demolition began on September 6, 2011.[111] Demolition was shortly thereafter halted for a historical preservation review, but historic designation was denied and the entire structure came down in March 2012.[112] The Walmart opened on December 2, 2013. The new structure included bricks and trusses from the original car barn, which is all that remains of it.[113]

Stations and loops

editA few stations and terminals have survived.

Sometime after conversion of the Mt. Pleasant Line in December 1961, the Dupont Circle streetcar stations were used as a civil defense storage area for a few years and then left empty again. The space was once considered for a columbarium.[114] In 1993, one of the stations was opened as a food court called DuPont Down Under; it closed after 18 months.[115] In 2007, D.C. Council member Jim Graham considered allowing adult-themed clubs to move into the property.[114] Since 2016, it has been an arts space managed by a nonprofit called Dupont Underground.[116]

The Colorado Avenue Terminal on 14th Street NW is in use as a Metrobus stop.

The Calvert Street loop just east of the Duke Ellington Bridge is used as a Metrobus turnaround loop.

A streetcar station in the center of Barney Circle was removed in the 1970s.[117]

The streetcar turnaround at 11th and Monroe NW is now the 11th and Monroe Streets Park.

Tunnels

editThis may contain excessive or inappropriate references to self-published sources. (March 2020) |

The Dupont Circle streetcar station tunnel entrances, located where the medians of Connecticut Avenue NW now stand, north of N Street NW, and between R Street NW and S Street NW, were filled in and paved over in August 1964, leaving only the traffic tunnel.[115]

The C Street NW/NE tunnel beneath the Upper Senate Park remained in use as a one-way service road adjacent to the Capitol, but since 9/11 it has been closed to the public.[118]

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing underground loop is now part of a parking structure and storage area that is located directly underneath 14th Street SW. Tracks can still be seen in the floors in some locations of the Bureau.[118]

Right-of-way

editThe right-of-way of the Glen Echo line is mostly extant from the Georgetown Car Barn all the way to the Dalecarlia Reservoir filtration plant in DC and from the District line to Cabin John in Maryland. The DC section includes an abutment near an entrance to Georgetown University, a trestle over Foundry Branch in Glover Archbold Park, the median of Sherier Place NW from Cathedral Avenue NW to Manning Place NW and a strip of land along most of the right-or-way.

Part of the right-of-way on the Georgetown campus was removed in the spring of 2007 to create a turning lane off of Canal Road NW. Bridge #1 at Georgetown University was removed in 1976.[119] The section from the aqueduct to Foxhall Road was purchased by the District of Columbia in the early 1980s to construct a crosstown watermain.[120]

In 1980 and 1981, the three other bridges along the right-of-way - Bridge #3 at Clark Place, Bridge #4 next to Reservoir Road, and Bridge #5 over Maddox Branch in Battery Kemble Park - were removed during the construction of the water main.[121] Bridge #6 over the Little Falls Branch Valley was removed sometime prior to 2000. The wide median of Pennsylvania Avenue SE from the Capitol to Barney Circle was built in 1903 to serve as a streetcar right-of-way.[92] It now serves as urban greenspace.

Other remnants

editPerhaps the most visible remnant of the streetcar system is the Metrobus system, run by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA). On January 14, 1973, WMATA purchased DC Transit and the Washington, Virginia and Maryland Coach Company (followed on February 4 by the purchase of AB&W Transit Company and WMA Transit Company) unifying all the bus companies in D.C.[122]

Many of today's WMATA's bus routes are only marginally changed from the streetcar lines they followed. For example, the #30 streetcar route that ran from Barney Circle to Friendship Heights is now the 30 bus line that runs from Anacostia through Barney Circle to Friendship Heights, and the #70 streetcar route to Brightwood is now the 70 bus that continues to run to Brightwood.[123]

Other remnants include the Potomac Electric Power Company, the electric portion of Washington Traction and Electric Company, which remains the D.C. area's primary electrical power company; some streetcar-related manhole covers that remain in use around town; and four tall lampposts for Capital Traction's overhead wires on the Connecticut Avenue bridge over Klingle Valley in Cleveland Park.[124] The poles likely date back to the bridge's construction in 1931.

The National Capital Trolley Museum holds in its archives an extensive collection of various artifacts from Washington's streetcar systems.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Tindall, Dr. William (1918). "Beginning of Street Railways in the National Capital". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 21. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society: 24–118. Retrieved February 19, 2010 – via Google Books..

- ^ a b c d e f g Lee, Virginia C.; Silverman, Cary (Winter 2005–2006). "Shaw on the Move Part II: Milestones in Shaw Transportation" (PDF). Shaw Main Street News. Shaw Main Streets. pp. 10–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ^ a b Bellis, Mary. "History of Streetcars and Cable Cars". Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2007.

- ^ McShane, Clay; Joel Tarr (September 2003). "The decline of the urban horse in American cities". The Journal of Transport History. 24 (2). Manchester University Press: 177–198. doi:10.7227/tjth.24.2.4. ISSN 0022-5266. S2CID 110374092.

- ^ Tindall, Dr. William (1918). "Beginning of Street Railways in the National Capital: The Washington and Georgetown Railroad Company". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 21. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society: 27. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2021 – via Google Books..

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cohen, Bob. "Washington, D.C. Railroad History". Washington, D.C. Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- Williams, Paul Kelsey (2001–2002). "Historic Survey of Shaw East Washington, D.C." (PDF). Washington History. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- Office of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia (1896). "Anacostia and Potomac River Railroad Company". Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Kraft, Brian (November 2003). "Petworth". DCNorth. Archived from the original on April 18, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c Trieschmann, Laura V.; Kuhn, Patti; Rispoli, Megan; Jenkins, Ellen; Breiseth, Elizabeth, Architectural Historians, EHT Traceries, Inc. (July 2006). "Washington Heights National Register of Historical Places Registration Form" (PDF). DC.gov: Office of Planning. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Office of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia (1896). Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Layman, Richard (February 2003). "H Street: A Neighborhood's Story Part II" (PDF). The Voice of the Hill. pp. 12–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2006. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ^ Office of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia (1896). "Anacostia and Potomac River Railroad Company". Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Eckmann, Alan; et al. (April 2004). "Anacostia Corridor Demonstration Project - Environmental Assessment" (PDF). District of Columbia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Ward, Mike (October 24, 2001). "Timeless Machines:Trolleys could make a homecoming to Richmond as the city eyes mass transit options". Richmond.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ Kulkulski, Ryan; Gallagher, Bill (March 7, 2000). "Washington's Trolley System" (PDF). WAMU. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Eckington and Soldiers Home Railway Company". Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. United States 54 Cong. 1. Sess. H. Doc.423. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896. pp. 81–95. OCLC 569582480. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^ Fuller, Melville (January 21, 1903). "Eckington & Soldiers' Home R CO v. McDevitt, 191 U.S. 103 (1903)". 9. The United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Commission, United States Interstate Commerce (1912). Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Reports and Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. L.K. Strouse. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b E.H.T. Traceries, Inc (June 2005). "Streetcar and Bus Resources of Washington, D.C., 1862-1962 / NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior / National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "Washington Neighborhoods". The United States National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Kimberly Protho Williams (2001). "Cleveland Park Historic District" (PDF). The Cleveland Park Historic District. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2007.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- "Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway Company". Laws Relating to Street-railway Franchises in the District of Columbia. United States 54 Cong. 1. Sess. H. Doc.423. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896. pp. 165–175. OCLC 569582480. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- EHT Traceries, Inc. (December 2019). "History Of The Washington & Great Falls Electric Railway" (PDF). Palisades Trolley Trail: Historic Resource Report for the Built Environment. Washington, D.C.: District Department of Transportation. pp. 3–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- King, LeRoy O. (1972). 100 Years Of Capital Traction: The Story of Streetcars In The Nation's Capital. College Park, Maryland: Taylor Publishing Company. pp. 47–52. ISBN 9780960093816. LCCN 72097549. OCLC 567981440. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved July 14, 2021 – via Google Books.

- "Washington and Great Falls Electric Railway" (advertisement). Washington, D.C.: The Morning Times. August 23, 1897. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ "Historical Overview Of Mount Rainier, Maryland". Historic Mount Rainier, Maryland. City of Mount Rainier. Archived from the original on July 28, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ "This Is His Birthday" (PDF). The Evening Star. January 17, 1908. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2007.

- ^ "Session Laws of Maryland 1894". 1894. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ Bentley, Elizabeth Marple (May 1999). "The District's Frontier in 1884: Tradesmen Join Visionary to Shape Washington's First True Suburb". Takoma Voice. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Washington (Map) (1903 ed.). Hammond, C.S. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Directory of Electric Railway Companies in United States, Canada and Mexico. New York: McGraw Hill Company Inc. 1920. p. 22.

East Washington Heights Traction.

- ^ Washington (Map) (1908 ed.). Hammond, C.S. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ Your National Capital (Map) (1917 ed.). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ^ "Hero of 1812 Remembered - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Map showing route of District of Columbia Suburban Railway : Sept. 1892". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ "Terminal of New Electric Road Booms Building in the Northeast". The Washington Times. Washington, DC. March 22, 1908. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- ^ Proctor, John Clagett (January 1, 1922). "Brightwood Proud of 30-Year Fight for Civic Improvement". Washington Herald. Archived from the original on July 21, 2024. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ "Takoma Park Historic District". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g March, Charles E. (August 1934). "The Local Transportation Problem in the District of Columbia". The Journal of Land and Public Utilities Economics. 10 (3). University of Wisconsin Press: 275–290. doi:10.2307/3139173. JSTOR 3139173.

- ^ a b Ganschinetz, Suzanne. "East Capitol Street Car Barn". Washington, D.C. Historic Places Travel Itinerary. The United States National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 30, 2005. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ "Anacostia and Potomac River electric streetcar". Dave's Electric Railroads: A collection of electric railroad, interurban, and streetcar photography from many eras. September 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "The Historic Car Barn". Douglas Development. Archived from the original on June 28, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Tindall, William (1918). "Beginning of Street Railways in the National Capita: Washington-Virginia Railway Company". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 21. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society: 46–47. Retrieved February 2, 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rehnquist, William H. (April 27, 2001). "Remarks at the Arlington Historical Society Banquet". United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Cohen, Robert (2003). "History of the Long Railroad Bridge Crossing Across the Potomac River". dcnrhs.org Washington, D.C. Chapter: National Railway Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- "Through the Most Historic Section of Virginia: Quickest, Most Convenient and Interesting Route to Mt. Vernon, Alexandria, Arlington .. National Cemetery .. via the Washington, Arlington & Mt. Vernon Railway". Industrial and Historical Sketch of Fairfax County, Virginia (Advertisement). Fairfax County Board of Supervisors. 1907. p. 90. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2014 – via Google Books.

- Snowden, William H. (1902). "Washington City to Mount Vernon: Stations And Distances". Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland, Described in a Hand-book for the Tourist Over the Washington, Alexandria and Mount Vernon Electric Railway] (3rd ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: G.H. Ramey & Son. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved January 13, 2013 – via Google Books.

- Washington-Virginia Railway Co. timetable in Victorian Society at Falls Church (2007). "6. An Era Ends: 1901-1915". Images of America: Victorian Falls Church. Charleston SC, Chicago IL, Portsmouth NH, San Francisco CA: Arcadia Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7385-5250-7. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved November 26, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Virginia Trolley Lines". Don's Depot. Archived from the original on September 20, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ^ Tindall, William (1914). Standard History of the City of Washington from a Study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, TN: H. W. Crew & Co. pp. 414–429.

Brightwood Railway Company.

In Google Books. - ^ City and Suburban Railway

- ^ Wright, William (2006). Now Arriving Washington: Union Station and Life in the Nation's Capital (PDF). p. 187. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 30, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schrag, Zachary M. (2006). The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 27–31. ISBN 978-0-8018-8246-3.

- ^ a b c "Washington Streetcar Collection". National Capital Trolley Museum. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Sabar, Ariel (May 1, 2008). "Adopting Meters, Washington Ends Taxi Zone System". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Capital Traction Company Electric Railway - District of Columbia". June 27, 2012. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. (Contains a 1948 track map of the Capital Transit Company published by the Electric Railroaders Association, Lackawanna Terminal, Hoboken, New Jersey)

- ^ District Of Columbia, United States. Congress. Senate (1924). Street-car Fares in the District of Columbia: Hearings Before a Subcommittee on S. 393, January 21, 1924. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Senate. p. 353. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Scheel, Eugene (February 18, 2007). "At the End of the Line, An Opportunity Lost". The Washington Post. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

...the railroad's passenger trains entered Washington via trackage across Aqueduct Bridge. But in 1923, when Francis Scott Key Bridge replaced the older span, the railroad gave up its right of way to the nation's capital. The new passenger terminal was in Rosslyn, on the Virginia side of the bridge.

- ^ Harwood, Herbert H. Jr. (April 2000). Rails to the Blue Ridge: The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, 1847 – 1968 (3rd ed.) (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "New Bus Company Files Entry Plea". The Washington Post. April 8, 1932. p. 11.

- ^ a b Druscilla, Null J. (December 7, 1983). "Historic American Buildings Survey: Columbia Railway Company Car Barns". United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ^ The last streetcar on the Anacostia-Congress Heights line ran on July 16, 1935.Eisen, Jack (August 3, 1985). "Metro Scene". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The History of the Georgetown Branch". Coalition for the Capital Crescent Trail website. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ "Lost from the Collections". National Capital Trolley Museum. Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ General Electric Company. "Capital Transit Company — Washington, D.C.: 489 PCC Cars in Service — 239 GE Equipped". D.C. Transit General Electric PCC data sheet: Bill Volkmer collection. davesrailpix.com. Archived from the original (adverisement) on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Flanagan, James (1942). Thirtieth Annual Report of the Public Utilities Commission of the District of Columbia (PDF). p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ North American Co. v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 327 U.S. 686 (1946), archived from the original.

- ^ "Strike Against Wolfson". Time. July 18, 1955. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- "Content Details: 70 Stat. 598 - An Act to grant a franchise to D. C. Transit System, Inc., and for other purposes (Public Law 84-757)". govinfo. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- "Public Law 757: Chapter 669: An Act to grant a franchise to D. 0. Transit System, Inc., and for other purposes" (text of statute). 70 STAT. 598-604. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. July 24, 1956. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "D.C. Transit 1304 - Seashore Trolley Museum". collections.trolleymuseum.org. Archived from the original on September 10, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ^ Regulation of D.C. Transit System, Inc.: hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, House of Representatives, Eighty-sixth Congress, first session, on H.R. 2316, H.R. 4163, and H.R. 4815, bills to insure effective regulation of D.C. Transit System, Inc., and fair and equal competition between D.C. Transit System, Inc., and its competitors (Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1959. p. 346. hdl:2027/ien.35556021313861. Archived from the original on October 4, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Crozet Man Is First Black Superintendent of D.C. Transit System". Charlottesville-Albemarle Tribune. January 28, 1971.

- ^ Cherkasky, Mara (2006). "Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail Brochure" (PDF). Cultural Tourism DC. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ "NCTM: Washington, D.C. Street Car Scenes". Archived from the original on February 3, 2007. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ^ "Trolley Buffs, Tipsy Students Race for Last Roundup Honors". The Washington Post. January 29, 1962.

- ^ "Transit News (Eastern)". Timepoints. The Southern California Traction Review. August 1959. Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Miklos, Frank (April–June 1997). "Barcelona" (PDF). Headlights: The Magazine of Electric Railways. 59 (4–6). Electric Railroaders Association, Inc.: 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ "DC Transit Company PCC Streetcar (1945)". The Virginia Museum of Transportation Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ Post, Robert. "Fourteenth and G, Washington, D.C. 1941". Technology and Culture. 39.

- ^ "Organizations Preserving North American Railway Cars". The Shore Line Trolley Museum. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- "Capital Traction 303" (description). Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- "Capital Traction 303" (2006 photograph). Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Paulson, Wesley. "Car History". Washington and Georgetown 212. Branford Electric Railroad Association (BERA). Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- "Streetcar Trailer No. 212". Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

This streetcar was originally built for the Pennsylvania Avenue route of the Washington and Georgetown Rail Road. After about 1898, it was converted to a trailer car which was coupled to an electric car. Its original number was "247," but it was renumberd "212" in 1898, and, later, as "1512". The car was restored in 1965 and retains the number "212".

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "DCTS 1101". Colesville, Maryland: National Capital Trolley Museum. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Capital Transit 1430 Archived May 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Capital Transit 1540 Archived April 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Capital Traction Company 09 Archived May 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Capital Traction Company 27 (ex-DC Transit 766 Archived May 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Capital Traction Company 522 Archived May 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Washington Railway & Electric Company (WRECo) 650 Archived May 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ National Capital Trolley Museum

- ^ "National Capital Trolley Museum - FRIDAY, JULY 17, 2020 - The National Capital Trolley Museum in Colesville, Maryland is pleased to announce our acquisition of historic DC Transit Company PCC street car No.1470 from the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke, VA. DC Transit 1470 was built in 1945 by the St. Louis Car Company and is of PCC (President's Conference Committee) design - the same as DC Transit 1101, 1430 and 1540 which already reside in the museum's collection. DC Transit 1470 is unique from the other Washington PCC cars in our collection; it is equipped with an automatic trolley catching device (notice the catching device on the roof holding the trolley pole.) An air motor replaced the traditional catcher and pulled the pole down to save manpower at plow pits. Both the release for the catcher and the air motor could be operated from the operator's position in the car. DC Transit 1470 was donated to the Virginia Museum of Transportation in 1964 by the President of DC Transit System, Inc., Mr. O. Roy Chalk, who donated many other historic street cars to the National Capital Trolley Museum. The National Capital Trolley Museum's Board of Trustees initially voted to acquire the car in late summer of 2019. On Wednesday, July 15, 2020, DC Transit 1470 was delivered to our facility in Colesville, Maryland. The arrival of this car on our campus marks the first time in many decades that the car is in a facility with other Washington street cars. We wish to extend a very special thank you to the many individuals and organizations who assisted with this acquisition, from the planning to the transportation, of this special car. We invite you to Like and Follow our Facebook and Instagram pages, subscribe to our TrolleyTime Blog and watch our website for additional information, photos and details regarding our acquisition of DC Transit 1470. Thank you for your continued support of the museum. | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Capital Transit 010 (description) Archived March 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Capital Transit 010 (2010 photograph) Archived July 16, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Orlando, Katie (July 2, 2020). "D.C. Transit 1304 makes its BIG Debut!". Kennebunkport, Maine: Seashore Trolley Museum: New England Electric Railway Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ History of North Texas Historic Transportation (2016)

- ^ "Leonard's Museum". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- 1999 photograph of car sold to Barcelona Archived August 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Undated photograph of car sold to Barcelona

- ^ "Museu del Transport". Archived from the original on November 28, 2007. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ^ Crowley, Susan (July 28, 1977). "Georgetown streetcar tracks paved; some are happy some are not". The Washington Post.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Walsh, Kevin (April 2, 2008). "Georgetown Trolley Tracks". Georgetown, DC, Trolley Ghosts. Little Neck, New York: Forgotten New York. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017.

- "Georgetown Streetcar Tracks: O and P Streets west of Wisconsin Avenue". Washington, D.C.: DC Preservation League. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "D.C. Transit". D.C. Streetcar Track and Structures. BelowTheCapital.org. Archived from the original on March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Georgetown Car Barn door". D.C. Transit. BelowTheCapital.org. April 2, 2008. Archived from the original (image) on March 24, 2011. Close-up photograph showing tracks and conduit.

- ^ Charnis, Elani (September 7, 2001). "Shopping in Georgetown". Washington Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 7, 2007. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ a b "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). September 2004. the Government of the District of Columbia. September 1, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c Regulation of Public Utilities in the District of Columbia: Hearing Before the Committee on the District of Columbia. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1920. p. 408.

- ^ "Richard Wright Public Charter School". Capital Riverfront. Washington, D.C.: Capitol Riverfront BID. 2021. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Hedgpeth, Dana (December 26, 2005). "Developer Buys 'Blue Castle' in Southeast". From The Ground Up. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Madison Marquette (November 24, 2014). "Madison Marquette Announces Sale of Navy Yard Car Barn". Cision PR Newswire. Chicago, Illinois: Cision Distribution. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Multiple Sources:

- Neibauer, Michael (November 14, 2014). "Madison Marquette, National Community Church close the Blue Castle deal". Washington Business Journal. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2021.