Canonbury House is the name given to several buildings in the Canonbury area of Islington, North London which once formed the manor house of Canonbury, erected for the Canons of St Bartholomew's Priory between 1509 and 1532. The remains today consist of Canonbury Tower and several buildings from the 1790s, some of which incorporate parts of the late 16th-century manor house. Today, the Tower and the other buildings, including a 1790s building today also named "Canonbury House", are arranged around the road named Canonbury Place.

| Canonbury Tower | |

|---|---|

Canonbury Tower from the northwest | |

| Location | Islington, London, United Kingdom |

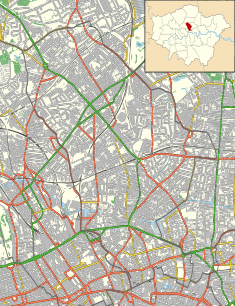

| Coordinates | 51°32′39″N 0°05′55″W / 51.54429°N 0.098611°W |

| Height | 66 feet (20 m) |

| Built | Between 1509 and 1532 |

| Built for | Prior and Canons of St Bartholomew's |

| Restored | 1907–08 |

| Restored by | 5th Marquess of Northampton |

| Current use | Masonic research centre |

| Architectural style(s) | Tudor |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Canonbury Tower |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1280424 |

| Site and remains of Canonbury House and gardens | |

|---|---|

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Canonbury House and Attached Walls and Railings |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1280446 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Numbers 1-5 (Consecutive) and Attached Garden Walls and Railings, 1-5, Canonbury Place |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1205846 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | 6-9, Canonbury Place |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1195507 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | 4A, Alwyne Villas (Tudor Garden House) |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1204135 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | 7, Alwyne Road (Tudor Garden House) |

| Designated | 20 September 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1195448 |

Canonbury Tower is a Tudor tower and is the oldest building in Islington. It is the most substantial remaining part of the old manor house, and is a Grade II* listed building, located 100 metres (330 ft) east of Canonbury Square.

Canonbury House and Canonbury Tower have been owned or occupied by many noted historical figures, including Thomas Cromwell, John Dudley, Sir Francis Bacon, Oliver Goldsmith and Washington Irving.

History

editThe buildings occupying the site of Canonbury House were developed, demolished or rebuilt in several phases.

Manor of Canonbury

editBefore the Norman Conquest the land now contained in the triangle formed by Upper Street, Essex Road and St Paul's Road was an Anglo-Saxon manor. Passing to Norman ownership, it finally became part of the vast estates of the de Berners family.[1] In 1253 Ralph de Berners made a grant of "lands, rents and their appurtenances in Iseldone" to the Prior and Canons of St Bartholomew's – an Augustinian order – in Smithfield. The area thus became known as the Canons' Burgh.[2] The manor lay alongside the village of Islington, between Upper Street and Essex Road (formerly called Lower Street), with a northern boundary at St Paul's Road (formerly called Hopping Lane), and from the early 17th century the southern verge was the New River.[3] The medieval manor house may have dated to 1362.[4][Note 1]

Prior Bolton's mansion and tower

editIn 1509 William Bolton was elected as the new Prior. Bolton substantially restored and added to St Bartholomew's, and was Henry VIII's Master of the Works for the building of the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey. In the 1520s Bolton also restored the medieval Canonbury manor house as a mansion for himself, his Canons and his successors.[6] It is uncertain how much of the Canonbury House that took shape in the 16th century was Prior Bolton's work, and most of its appearance is unknown, although its layout is still discernible today, with a range of buildings around a courtyard, and the six-storey Tower.[7] Canonbury Tower is certainly his work; some sources give the date for the Tower as c. 1562, but this is incorrect as Prior Bolton died in 1532 and was succeeded by Robert Fuller.[8] The reason for constructing the Tower is obscure since it served no defensive purpose. However, the flat roof commanded a fine view of Middlesex and the City;[9] even in 1807 it was observed that "Canonbury was certainly most convenient and pleasant. We can easily imagine the beautiful view they must have had from thence, even to the gates of the priory; for the smoke of London was not then so dense as it is at present; and but very few buildings intervened."[10]

The grounds were enclosed with a brick wall, extending from the rear of the present Alwyne Road houses northward to St Paul's Road.[5]

When the monasteries were dissolved by Henry VIII, St Bartholomew's and its appendages were among the last to be taken. Prior Robert Fuller surrendered the Priory and its lands to the Crown on 25 October 1539.[11] Henry VIII bestowed the manor of Canonbury on his Chief Minister for the Dissolution, Thomas Cromwell,[12] only a year before his execution on 28 July 1540.

In 1547 the manor was granted by Edward VI to John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, later Duke of Northumberland. He was executed in 1553 for his abortive attempt to place his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, on the throne. Queen Mary I in 1556 granted the manor to one David Broke, and in 1557 to Thomas Wentworth, 2nd Baron Wentworth, who seems to have undertaken some building there.[13]

John Spencer's "Old Canonbury House"

editJohn Spencer initially leased the House and Tower from Wentworth for £21.11s.4d, and then bought it in 1570 for £2,000.[14] Spencer was popularly known as "Rich Spencer"[4] and he amassed one of the greatest private fortunes of his day. Queen Elizabeth is said to have visited him at Canonbury in 1581.[15] He rose to become Sir John Spencer, Knight, Lord Mayor of London in 1594. Spencer took up regular occupation of Canonbury House in 1599 as a country house, and modernised the House and Tower to make them inhabitable and added the main embellishments such as stuccoed ceilings, oak panelling and oak chimney-pieces, many of which still exist and date from that period.[9] Thereafter it is often hard to determine whether individuals were resident in the House or in the Tower, with the names being used interchangeably. Spencer's house is often referred to as "Old Canonbury House". In 1605 the Lord Chancellor, Thomas Egerton, later Earl of Ellesmere, issued a charter dated at Canonbury House and was presumably visiting.[16]

The layout of Spencer's Canonbury House seems to have been east, south and west ranges surrounding a courtyard, with the Tower at the north-west corner, and stables nearby.[9][Note 2] Contemporary engravings show a bell turret with a cupola stood above the east range, known as Turret House.[1] Canonbury House's walled grounds included gardens below the south range.[18] The southern corners of the gardens were marked by the two Tudor octagonal garden or summer houses which still stand today. On the north side were gardens which at an unknown later date contained a large fish pond.[19] The House and gardens stood in open agricultural and dairy fields with views towards London.[20]

Spencer had no son but had a daughter, Elizabeth. She had fallen in love with William Compton, 2nd Baron Compton, who succeeded his father in 1589 when only 21 and went to the royal court of Queen Elizabeth, borrowing from John Spencer[21] when he had spent what his father had left him. Spencer did not regard marriage to his daughter as a suitable way of liquidating the debt, so he opposed it and confined his daughter in Canonbury Tower.[22] She and Lord Compton eloped: supposedly the young lord, disguised as a baker's boy, drove his cart over the fields to Islington and Elizabeth Spencer was lowered from a window in a baker's basket and escaped to marriage in 1599.[23] Sir John disowned his daughter, costing the couple a fortune variously estimated at from three hundred to eight hundred thousand pounds. However, a son was born to the Comptons in 1601, and Spencer was partially reconciled through the efforts of the Queen, saying that having now no daughter he would adopt the child as his son. The reconciliation was completed with the birth of a second child, a daughter,[24] in Canonbury House[25] and the immense fortune found its way to them on Spencer's death in 1610. Compton then became "in great danger to loose his witts" and later "so franticke that he is forced to be kept bound". He recovered, and then spent "within lesses than eight weekes...£72,000, most in great horses, rich saddles and playe",[24] and on gambling, entertaining and extending the country seat at Castle Ashby House, Northamptonshire, and not on Canonbury House, which was let. The young lord eventually became Lord President of the Council in 1617, and in 1618 was created 1st Earl of Northampton.

From 1616 to 1625 the House was leased to Sir Francis Bacon, philosopher and statesman, who was at first Attorney General and the year after Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. He became "lessee from Lord and Lady Compton of the ‘Mansion house and garden thereunto belonging called Canbury House’, together with some adjacent fields."[26]

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, politician and statesman, lived in Canonbury House between 1639 and 1641.[27] He later held senior political office under both the Commonwealth of England and Charles II.

In the English Civil War, Spencer Compton, 2nd Earl of Northampton and his six sons supported the King's cause. The Earl was killed at the Battle of Hopton Heath. The family was fined £40,000 during the Commonwealth, sold property and mortgaged Canonbury House, where they took up residence. The mortgage dated 1661 included "all that capital messuage and Mansion House commonly called Canonbury alias Canbury House, and all that tenement called the Turret House situated and being at the end of the courtyard and the Park, to secure £1751". A son was born to James Compton, 3rd Earl of Northampton at Canonbury House in 1653 and another died aged five in 1662. No other Earl or Marquess of Northampton has since resided there.[28]

In the 1750s, some of the mansion's outbuildings and former stables became a tea-garden called, confusingly, "Canonbury House".[29] Later renamed Canonbury Tavern, or Canonbury House Tavern, it had a bowling green, gardens, and accommodated corporate, parochial and club dinners. From 1808, the facilities on offer included a shrubbery, bowling green, Dutch-pin and trapball grounds, and a butt used for firing practice by Volunteers and others.[30] It was rebuilt c. 1846 as the Canonbury Tavern,[31] which Benjamin Disraeli mentions in his 1880 novel Endymion.[32]

Letting of Canonbury House and Tower

editDuring the 18th century Canonbury House and Tower were let, part of them in separate rooms, and often as summer lodgings to gentlemen seeking a rural retreat close to London.[33][3] An advertisement of 1757 described furnished or unfurnished apartments with a good garden, summer house and coach house, and access to an excellent cold bath.[1] Canonbury House was still enclosed by the brick wall that sloped down to the New River running through the Islington dairy fields, and was a restful spot for visitors seeking peace.

At Christmas 1762 the novelist, playwright and poet Oliver Goldsmith took a room in the House which he occupied for about eighteen months, allegedly often using it to hide from his creditors. It is uncertain whether any of his novel The Vicar of Wakefield was written in Canonbury Tower, where tradition has it that Goldsmith occupied the Spencer Room. On Sunday, 26 June 1763 James Boswell noted in his London Journal: "I then walked out to Islington to Canonbury House, a curious old monastic building now let out in lodgings where Dr. Goldsmith stays. I took tea with him and found him very chatty."[34] In the summer of 1767 Goldsmith again lodged at Islington, this time in the Turret House.[35]

An earlier literary lodger was Samuel Humphreys whose libretti for three of Handel's early oratorios – Esther, Athalia and Deborah – date from 1730 to 1738, when he died in Canonbury House.[36] Handel "had a due esteem for the harmony of his numbers".[37]

The publisher John Newbery was in residence between 1761 and 1767.[38] Newbery wrote numerous books for the young with titles such as "Logic made familiar and easy". His best known creation was Goody Two-Shoes.

The troubled poet Christopher Smart was allowed by Newbery to live at Canonbury House in the 1750s.[39]

Ephraim Chambers, an encyclopaedist whose principal work was the Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, published in 1728, died there in 1740.[4] He was unrelated to the founders of the 19th-century Chambers's Encyclopaedia.

Another lodger was the printer and journalist Henry Sampson Woodfall,[4] who edited the Public Advertiser in which from 1769 for three years the Letters of Junius appeared, to the great discomfiture of the government. Woodfall was tried for printing the letters and accused of seditious libel, but went free after the judge decided in favour of a mistrial. His grandfather Henry Woodfall invented the characters Darby and Joan.

Other lodgers included Arthur Onslow, Speaker of the House of Commons; Deputy Harrison, for many years printer of the London Gazette; and Robert Horsfield, successor to Messrs. Knapton, Alexander Pope's booksellers.[4]

Remodelling of Old Canonbury House

editIn 1767 the 8th Earl of Northampton’s family fortunes were at a low ebb, and he leased the empty Canonbury House and adjoining grounds including the large fish pond[Note 3] for 61 years to Mr John Dawes, a City stockbroker. Dawes added bay windows to the Tower and demolished the Turret House and part of the wall surrounding the grounds. In a significant change he demolished the entire south range of Spencer's Old Canonbury House and on its site built "elegant new villas", the Georgian houses now numbered 1–5 Canonbury Place, overlooking the garden. These he leased to the earl and occupied one himself.[42] The turret was taken down[43] and much of the east range was divided, reclad or rebuilt as a row of terraced houses incorporating some of Spencer's range. These are now the buildings numbered 6–9 Canonbury Place. Much of the Tudor plasterwork,[44] joinery[45] and stairs were left intact and can be seen today,[38] despite the removal of a chimneypiece and some wood panelling to the Northamptons’ country house Compton Wynyates.[46]

In the 1790s, a small mansion for which no records survive was built adjoining the Tower, partly filling the west side of the old manor house court. This building is today called, again confusingly, "Canonbury House".[3]

In the early 19th century Washington Irving, creator of Rip Van Winkle, hoped to be inspired by Goldsmith's muse and engaged his room – reputedly the Spencer Room – at the Tower, which he referred to as "Canonbury Castle". He remained only a few days. When Sunday came he was disturbed by noise, and his "intolerable landlady" was perpetually bringing parties of visitors not only up to the Tower but into the room where he was working. He remonstrated, locked the door and pocketed the key, only to hear the landlady allowing the visitors to peep through the keyhole at the "author who was always in a tantrum when interrupted". He wrote:[47]

"I could not open my window lest I was stunned with shouts and noises from the cricket ground, the late quiet road beneath my window was alive with the tread of feet and the clack of tongues; and, to complete my misery, I found that my quiet retreat was absolutely a ‘show house’, the tower and its contents being shown to strangers at sixpence a head…So I bade adieu to Canonbury Castle, Merry Islington, and the haunts of poor Goldsmith without having advanced a single line in my labours."

Charles Lamb, essayist, poet, and antiquarian, loved to visit the Tower when he lived in Islington. He was "never weary of toiling up the steep winding stairs and peeping into its sly comers and cupboards".[48] He also enjoyed the view from the top.[49] A book written in 1835 still speaks of its being possible to see from there "the adjacent villages and surrounding countryside".[50]

From 1826 to 1907 the tower was the home of the bailiff of the estate. In 1885 it is described as being in a sadly dilapidated state. "Although the exterior looks substantial enough, and the splendid carved wood panelling is intact, all the rooms are deserted and many are decaying".[51] It was afterwards rented by the Islington C of E Young Men's Society, followed by the Canonbury Constitutional Club from 1887 to 1907.[1]

In 1907 an American advocate of the Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship travelled to England. She believed she had decoded a message which revealed that Francis Bacon's secret manuscripts were hidden behind panels in the Tower.[52][53] None were found.

1 Canonbury Place was formerly the home and office of architect Sir Basil Spence from 1956 to 1976, who is commemorated there with a plaque.[54]

5 Canonbury Place was the home of Weedon Grossmith, co-author of The Diary of a Nobody, from 1891 to 1899.[23]

6 Canonbury Place was a ladies’ school as early as 1838, and was c. 1855 called "Northampton House", kept by Miss Caroline Bifield. Nos. 6–7 were recombined in 1868 and were later the premises of Highbury and Islington High School for Girls until its closure in 1911.[23] The school was opened in 1878 by the Girls' Public Day School Company, in connection with the National Union for Improving the Education of Women. It offered a broad education with preparation for Oxford and Cambridge Schools Board examinations. Its first head was Miss M. C. Whyte. There were 215 pupils in 1884, with a kindergarten, and in 1908 it was a recognised secondary school with 144 girls.[55] From 1930–65, it was the headquarters of the North London (Islington) District Nursing Association, and subsequently became Harcourt House (Medical Missionary Association)[23] until 1988, then a residential meditation centre.

8–9 Canonbury Place were recombined about 1908, and were used as Canonbury Childrens’ Day Care Centre until 1990.

19th century development of the grounds adjoining Canonbury House

editTo the west of the grounds of Canonbury House, the 1st Marquess of Northampton made a building agreement in 1803 with Henry Leroux of Stoke Newington for a large area fronting Upper Street, Canonbury Lane, and Hopping Lane (St Paul's Road). Compton Terrace, on the east side of Upper Street, was started by 1806. Leroux started building the north-west range of Canonbury Square in 1805. In 1812, when few properties had been built, the New North Road turnpike, now known as Canonbury Road, was constructed and bisected the square, creating east and west sides.[56]

In the north-east: in 1837 Charles Hamor Hill, London District Surveyor, leased the Tower from the 2nd Marquess of Northampton. Hamor Hill subsequently negotiated a licence with the Marquess to build three roads in the surrounding meadows which became Canonbury Park North (c. 1863) and South (c. 1850-52) and Grange Grove (c. 1851, formerly Grange Road) where, by 1850, he had constructed 50 villas.[57]

In the south and south-east: in1847 the Marquess and James Wagstaff made a building agreement for the land between Alwyne Villas and the gardens of Canonbury Park South, which included the 16th-century garden and summer houses of Canonbury House. There he built the villas on the east side of Alwyne Villas, in Alwyne Road and Alwyne Place, and Willow Bridge Road. The earliest houses were 2 and 4 Alwyne Villas, described as 'cottage villas', and 1-4 Alwyne Road, all leased to him in 1848. 6-16 Alwyne Villas followed in 1849 and leases of the remaining houses gradually up to 1860.[58]

It is unclear whether 14 Alwyne Place (early 18th to early 19th century)[59] or 16 Alwyne Place (late 17th to early 19th century)[60] were ever part of Canonbury House, although they appear on many old maps, and may have become separated from it by the construction of Alwyne Place.

Developments to the north towards St Paul's Road included St Mary's Grove (c. 1848, formerly St Mary's Road), and Compton Road (c. 1850-51).[61]

Restoration and reuse of Canonbury Tower

editIn 1907–08 the 5th Marquess of Northampton completely restored the Tower, preserving the original features where rebuilding was necessary. The ivy was removed: before removal, one main trunk of ivy was 9 inches (0.23 m) thick and the growth had made holes 3 feet (0.91 m) square in the brickwork. The iron railings round the top of the Tower were replaced by a brick parapet; and some of the old oak roof beams were used for restoration. A new building was erected adjacent to the Tower, King Edward's Hall; it served as a recreation hall and with the Tower itself formed the premises of a social club for the residents of the Marquess's Canonbury and Clerkenwell estates.

In 1924 the Francis Bacon Society was granted a tenancy of part of the gabled building east of the Tower, and made its headquarters there with its remarkable library.

Early in 1940, when many of the estate tenants had been evacuated and a large proportion of the houses were standing empty, the social club surrendered its tenancy. Shortly afterwards, for fear of damage by enemy action, the 16th-century oak panelling and chimney pieces in the Compton and Spencer Rooms were taken down section by section for storage at Castle Ashby House, the seat of the Marquess, until the war ended. The damage caused by bombing to the historic buildings in Canonbury was negligible. From 1941 onwards, Canonbury Tower and King Edward's Hall were used as a youth centre for the benefit of some 300 boys and girls, most of whom were living on the estate. After the war, the youth centre was rehoused elsewhere on the estate. The panelling and chimney pieces were brought back, cleaned and restored under the supervision of the Keeper of Woodwork at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and reinstated. The Marquess provided suitable furniture for the Compton and Spencer Rooms and the great brass chandeliers which now light those rooms.

In 1952, the Tavistock Repertory Company took a lease of the Tower and King Edward's Hall. As the Tower Theatre Company it mounted nearly 1600 productions in the hall, ending when the lease expired in 2003.

Present-day

editAs early as 1943, the Trustees of the Northampton Estate decided that when the war was over, they would redevelop much of the Canonbury estate. Many properties had suffered war damage and dilapidation and were considered ‘too large and draughty’. Large Victorian villas were demolished and replaced in Canonbury Park North and South, and Grange Grove.[62]

In 1954 the Northampton Estate sold the majority of the remains of the old manor to two property companies, Western Ground Rents (jointly controlled by insurers Clerical Medical and Equity & Law) and Oriel Property Trust. Streets which were restored or renewed to the north included St Mary's Grove, Grange Grove and Prior Bolton Street.[63]

In 1971 local residents successfully campaigned to prevent the redevelopment of Alwyne Road, Alwyne Place and Alwyne Villas as three- and five-storey blocks of flats.[64]

The Observer commented in 1965 that the Northampton Estate retained "about 250 tenants and leases property for £300 to £1000 a year, and more". Today the Estate's residual Canonbury ownership (including Canonbury Tower) is concentrated in and around Canonbury Place and "The Alwynes" (q.v.), though freeholds there have been gradually sold off.[65]

"Canonbury House"

editToday's Canonbury House partially occupies, with Canonbury Tower, the site of the west range of Spencer's Old Canonbury House. It is a detached Grade II listed building bearing the name “Canonbury House” above its front door, and is a private residence. It dates to c. 1795, with the stone pedimented dormers added c. 1900. It was formerly known as St Stephen's Vicarage when it was the clergy house residence for St Stephen's Church, which is nearby on Canonbury Road.[66]

John Hextall (1861–1914), founder of the community of Bowness, now part of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, was born here.[67]

1–5 Canonbury Place

editThe site of the south range of Old Canonbury House is occupied by 1–5 Canonbury Place,[68] which are all private residences. No. 5 displays the name “The Old House” above its front door. External shots of nos. 1–6 appear in the films Corridors of Blood (1958)[69] and David Copperfield (1968).[70]

6–9 Canonbury Place

editNos. 6–9 occupy the site of the east range of Old Canonbury House. On many old maps these buildings are often shown as "Canonbury House", and sometimes referred to as "Old Canonbury House". Some parts of the buildings still contain remnants from John Spencer's Tudor building, including stuccoed ceilings and oak carvings. The buildings are significant for the quality, scarcity and survival of the 16th-century plasterwork, for the survival and scarcity of the joinery of the 16th-century stair, for the 16th-century structural timbers, and for the internal joinery, panelling and staircases from the late 18th- and early 19th-century.[71]

In 1993, nos. 6–7 were linked with nos. 8–9 for use as a conference centre named Canonbury Academy. A persistent local rumour is that the academy was an MI5 training centre.[72]

Since 2014, nos. 6–9 have been the premises of North Bridge House Senior School.

10–14 Canonbury Place

editNos. 10–14 is a row of terraced houses incorporating shops, dating to the mid-19th century[73] and built on the site of the north boundary of the courtyard of Old Canonbury House.

"The Alwynes" and Tudor garden houses

editThe gardens to the south of 1–5 Canonbury Place were formerly the gardens of Canonbury House, and are now bordered by the Victorian houses of Alwyne Villas, Alwyne Road, and Alwyne Place, which are referred to locally as "The Alwynes", after a family name of the Northamptons.

Two octagonal Elizabethan garden houses, at 4a Alwyne Villas[74] (showing exposed brickwork) and 7 Alwyne Road[75] (with brickwork rendered in cement) mark the former extent of the gardens, near the course of the New River.[76] Nearby is a small circular brick building with a conical tiled roof which was possibly a 17th-century former watchhouse, once used by watchmen to prevent bathing or fishing in the New River.[23][77][Note 4] The garden house at no. 4a displays a carved ‘bolt’ or arrow piercing a ‘tun’ or barrel, a punning rebus by Prior Bolton on his own name.[7][Note 5]

Canonbury Tower

edit(based on Canonbury Tower: a Brief Guide):[80] Since 1998 the Tower has been used as a Masonic research centre.[81] It can occasionally be visited as part of a guided tour.

There is a tradition that Bacon planted the old red mulberry tree that still flourishes in the garden next to the Tower,[82] to encourage the home production of silk; however, silk worms prefer the white mulberry.[28]

Description of Canonbury Tower

editThe Tower is 66 feet (20 m) high and about 17 feet (5.2 m) square. The brick walls vary in thickness from 4 feet (1.2 m) to 2 feet 6 inches (0.76 m).[83] The main entrance hall leads into a low hall adjoining the Tower itself, and on the ground floor is a room with the original brickwork exposed.

Spencer Room

editThe room on the first floor commemorating the occupancy and work of Sir John Spencer is the plainer of the two panelled rooms. The chimneypiece is the most elaborate part, with lions' heads. At the top just below the ceiling there are three curious carved figures like the figurehead of a ship and there is another, which has lost its head, at eye level in the centre, just below a pair of bellows. There is strapwork ornament on the underside of the mantelpiece, and at either side Tudor roses in what might be garters prefigure or reflect the Rosicrucian interests of Sir Francis Bacon.[84] The same pattern is found on the upright pillars of the Great Bed of Ware. Twelve flat pilasters run from floor to ceiling.

By the end of the 16th century the Italian workmen who had come over to help Henry VIII on his various projects – the tomb of Henry VII and Greenwich and Whitehall Palaces – had mostly gone back and the workmanship is probably mainly Flemish.

Compton Room

editOn the second floor the panelling is more elaborate, of the type called "panel within panel", and there is liberal use of strapwork on the ten pilasters. The chimneypiece again is elaborate, with figures of Faith (one knee exposed, one arm missing) and Hope in a border of flowers and abstract pattern. The Latin inscribed beneath Faith – Fides Via Deus Meta – means "Faith is my way, God is my aim", and under Hope – Spes Certa Supra – means "My sure hope is above". The frieze over the fireplace consists of pomegranates and exotic fruits. Elsewhere it is a shell pattern, with at various intervals the arms of Spencer (argent two bars gemelle between three eagles displayed sable) and semi-grotesque heads. On the east side the panelling has been moved forward to provide another room, which contains bricked up a mullion window of the original type – replaced by windows of seasoned Oregon pine elsewhere in these rooms. The room is now all that remains of the occupancy of the Francis Bacon Society. Over the main door there is a carving known as a "cresting" incorporating a spread eagle.

Staircase

editThe Tower, whose core is the central staircase, has a stairway in short straight flights and quarter landings, with the centre filled in with timber and plaster forming a series of cupboards.[85] The black oak of the balusters is mostly original timber. At the top, the handrail newel and baluster are cut from sound oak beams found among the woodwork during the restoration of 1907–08: four centuries old but when sawn still fresh and sweet smelling.

Inscription Room

editThe space below the roof forms a small room, once presumably a schoolroom, containing a list of the Kings and Queens of England, from Will Conq to Carolus qui longo tempore in rough Latin and Norman French hexameters. There is also a mnemonic in Latin elegiac which can be translated as "Let your thoughts be on your own death, the deceits of the world, the glory of heaven and the pains of hell". On the roof itself, which was not originally flat, is a weather vane said to be copper. The iron railings originally there are now at ground level at the front of the building.

In literature

edit- Charles Dickens wrote a short story in 1838 about a lamplighter in Canonbury, which features Canonbury Tower.[86]

- George W. M. Reynolds’s popular novel Canonbury House; or, the Queen's Prophecy was serialised in the penny dreadful Reynolds's Miscellany between 11 July 1857 and 1 May 1858.[87]

- In the 2014 novel Death and Mr Pickwick, the author Stephen Jarvis describes the illustrator Robert Seymour in his youth taking a room at Canonbury Tower. Seymour is known for his illustrations for Dickens's The Pickwick Papers. The novel also briefly describes the residencies of Oliver Goldsmith and Washington Irving at the Tower.[88]

Nearest stations

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ The date of the medieval manor house is disputed.[5]

- ^ It is also possible that there were two courtyards, and the "east range" (today’s 6–9 Canonbury Place) was actually a central range.[17]

- ^ Contemporary maps do not seem to show the pond. It still appears in the two images shown in this article, dated 1827 and 1846. It is described as in 1815 abounding "in gold and silver fish",[40] and is mentioned in Lewis’s 1842 survey.[41]

- ^ Cosh believes the watchhouse on the New River is more likely to be a late 18th-century building, possibly used by a lengthsman working on the New River.[78]

- ^ A similar rebus can also be seen above one of the old monastic doors which remains inside 6 Canonbury Place.[79]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Baggs, Bolton & Croot 1985, pp. 51–57.

- ^ Fincham 1912.

- ^ a b c Cosh 1993, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Thornbury 1878.

- ^ a b Tomlins 1858, p. 194.

- ^ Stow 1603.

- ^ a b Cosh 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Cosh 2005, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Cosh 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Lewis 1842, p. 88.

- ^ Oakley 1980, p. 2.

- ^ Brewer.

- ^ Cosh 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Oakley 1980, p. 3.

- ^ Welch 1898, p. 357.

- ^ Lewis 1842, p. 94.

- ^ "Old Canonbury House in Canonbury Place" (photograph). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. 1942. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "A south view of Canonbury House near Islington" (etching). The British Museum. John Boydell. 1750–1760. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "North West View of Canonbury" (etching and engraving). The British Museum. Thomas Cook. c. 1780. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Birds-eye view from Canonbury Tower, Islington" (print). The British Museum. 1819. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Chamberlain 1939.

- ^ Public Record Office.

- ^ a b c d e Willats 1986, p. 40.

- ^ a b Zwart 1973, p. 91.

- ^ Cosh 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Tomlins 1858, p. 112.

- ^ Airy 1887, p. 111.

- ^ a b Oakley 1980, p. 6.

- ^ Wroth, Warwick (1896). The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. pp. 154–155. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Willats 1986, p. 41.

- ^ Cosh 2005, p. 94.

- ^ DIsraeli, Benjamin (1880). Endymion. London: Longmans & Green. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Lysons 1795.

- ^ Boswell 2004.

- ^ Stephen 1890, p. 91.

- ^ Watt 1891, p. 251.

- ^ The Daily Post 1738.

- ^ a b Oakley 1980, p. 8.

- ^ Sherbo 1967.

- ^ Nicholson, Renton (1860). The Lord Chief Baron Nicholson: An Autobiography. London: George Nicholson. p. 2. ISBN 9780598981950. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Lewis 1842, p. 92.

- ^ Cosh 2005, p. 121.

- ^ Tomlins 1858, p. 197.

- ^ "Interior detail of old Canonbury House in Canonbury Place" (photograph). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. 1912. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Interior of old Canonbury House in Canonbury Place" (photograph). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. 1912. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Salzman 1949.

- ^ Irving 1824.

- ^ Daniel 1863, p. 14.

- ^ Zwart 1973, p. 111.

- ^ Oakley 1980, p. 10.

- ^ Welsh 1885.

- ^ Shapiro 2010, p. 144 (127).

- ^ Wadsworth 1958, p. 64.

- ^ "SPENCE, Sir Basil (1907-1976)". Blue Plaques. English Heritage. 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Old Canonbury House in Canonbury Place" (photograph). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. 1912. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Baggs, Bolton & Croot 1985, pp. 19–20.

- ^ "Placing Canonbury: Piecing Together a House's History" (PDF). The Canonbury Society Newsletter. 2021. p. 2.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1298140, 14 Alwyne Place.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1195446, 16 Alwyne Place.

- ^ Willats 1986, pp. 214, 58.

- ^ Lambert, Jack (2018). "Louis de Soissons Cottages" (PDF). The Canonbury Society Newsletter. p. 2.

- ^ Cosh 1993, p. 116.

- ^ Lambert, Jack (2011). "Canonbury Society 40 Years On: Key Dates in Our History" (PDF). The Canonbury Society Newsletter. p. 4.

- ^ Ireland, David (2010). "Who Owns Canonbury?" (PDF). The Canonbury Society Newsletter. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1280446, Canonbury House.

- ^ Carole, J. (2005). "John Hextall and Bowness Estates". Bowness - Our Village in the Valley. Calgary, Alberta: Bowness Historical Society. pp. 19–44. ISBN 9781553830948.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1205846, 1–5 Canonbury Place.

- ^ "Corridors of Blood". ReelStreets. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "David Copperfield". ReelStreets. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1195507, 6–9 Canonbury Place.

- ^ Ireland, David (2017). "'Safe Houses I Have Known'" (PDF). The Canonbury Society Newsletter. p. 4.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1205925, 10–14 Canonbury Place.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1204135, garden tower, 4a Alwyne Villas.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1195448, garden tower, 7 Alwyne Road.

- ^ Lempriere, C. (1731). "South view of Canonbury House, Islington" (engraving). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1280628, Watch House on the North Side of the Road and the South Side of the New River, Canonbury.

- ^ Cosh 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Historic England, list entry 1195507.

- ^ Oakley 1980, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Canonbury Masonic Research Centre.

- ^ Coles, Peter (15 March 2018). "Canonbury's heritage mulberry". Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Oakley 1980, p. 11.

- ^ Yates 2002, chapter IX.

- ^ "Interior of Canonbury Tower in Canonbury Place" (photograph). London Picture Archive. Corporation of London. 1942. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ The Lamplighter Charles Dickens (Public Domain) accessed 29 September 2009

- ^ Reynolds, George W. M. (11 July 1857). "Canonbury House; or, the Queen's Prophecy". Reynolds's Miscellany. Vol. 18, no. 470. pp. 369–373. ProQuest 2864744. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Jarvis, Stephen (2014). Death and Mr Pickwick. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9780224099660.

Sources

edit- Airy, Osmund (1887). "Cooper, Anthony Ashley (1621–1683)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 111–130.

- Baggs, A. P.; Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C., eds. (1985). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8, Islington and Stoke Newington Parishes. London: Victoria County History. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Boswell, James (January 2004). London Journal 1762–1763. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300093012. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Brewer, J. S. "Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 5, 1531–1532". British History Online. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Canonbury Masonic Research Centre. "History of Canonbury Tower". Canonbury Masonic Research Centre. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Chamberlain, John (1939). The Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 1. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Cosh, Mary (1988). An Historical Walk along the New River (2nd ed.). London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. ISBN 0-9507532-3-8.

- Cosh, Mary (1993). The Squares of Islington: Part II. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. ISBN 0-9507532-6-2.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-948667-97-4.

- Daniel, George (1863). Love's Last Labour Not Lost. London: B. M. Pickering. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Fincham, Henry. W. (1912). "An Historical account of Canonbury Tower". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 18 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1080/00681288.1912.11893802. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Historic England. "Historic Site Listing". List of Protected Historic Sites. Historic England. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- Irving, Washington (1824). Tales of a Traveller, by Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Lewis, Samuel (1842). The History and Topography of the Parish of Saint Mary, Islington, in the County of Middlesex. London: Jackson J. H. ISBN 978-1173880927.

- London Borough of Islington. "Planning Application Search". Planning Applications. London Borough of Islington.

- London Metropolitan Archives. "London Picture Archive". London Metropolitan Archives. City of London Corporation. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- Lysons, Daniel (1795). The Environs of London: Volume 3, County of Middlesex. London: T Cadell and W Davies. pp. 123–169. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Nelson, John (1811). The History, Topography, and Antiquities of the Parish of St. Mary Islington, in the County of Middlesex. ISBN 978-1241600754.

- Nichols, John (1788). The History and Antiquities of Canonbury-House, at Islington, in the County of Middlesex. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-1379988045.

- Northampton, 6th Marquess of (1926). "Article – title unavailable". Country Life.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Oakley, Richard (1980). Canonbury Tower: a Brief Guide (booklet, based on Richard Oakley's Brief History of Canonbury Tower). London: Tavistock Repertory Company.

- Public Record Office. Recognisances for Debt, 192. The National Archives.

- Radford, Ernest (1886). "Bolton, William". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 5. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 333.

- Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (1925). An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Volume 2, West London. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 63–67. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- St Mary's Church, Islington. Parish Registers.

- Salzman, L. F., ed. (1949). "Parishes: Compton Wyniates". A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 5, Kington Hundred. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 60–67. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Shapiro, James (2010). Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? (US ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-4162-2. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Sherbo, Arthur (1967). Christopher Smart: Scholar of the University. Michigan State University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780870131103.

- Stephen, Leslie (1890). "Goldsmith, Oliver". In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 86–95.

- Stow, John (1603). A Survey of London. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750942401. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "The Daily Post". The Daily Post. 1738.

- Thornbury, Walter (1878). Old and New London: Volume 2. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin. pp. 269–273. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Tomlins, Thomas Edlyne (1858). Yseldon: A Perambulation of Islington. London: James S. Hodson; K. J. Ford. ISBN 978-1153222815.

- Wadsworth, Frank W. (1958). The Poacher from Stratford: A Partial Account of the Controversy Over the Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays. University of California Press.

- Watt, Francis (1891). "Humphreys, Samuel". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 250–251.

- Welch, Charles (1898). "Spencer, John (d.1610)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 53. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 357–358.

- Welsh, Charles (1885). A Bookseller of the Last Century. London: Griffith, Farren, Okeden & Welsh. p. 48. ISBN 978-0469561311. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Willats, Eric A. (1986). Islington: Streets with a Story. London: Islington Local History Education Trust. ISBN 0-9511871-04.

- Yates, Frances A. (2002). "Chapter 9". The Rosicrucian enlightenment (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0415267692.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. London: Sidgwick and Jackson Limited. ISBN 0-283-97937-2.