This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

The Canol Road was part of the Canol Project and was built to construct a pipeline from Norman Wells, Northwest Territories southwest to Whitehorse, Yukon, during World War II. The pipeline no longer exists, but the 449 kilometres (279 mi) long Yukon portion of the road is maintained by the Yukon Government during summer months. The portion of the road that still exists in the NWT is called the Canol Heritage Trail. Both road and trail are incorporated into the Trans-Canada Trail.

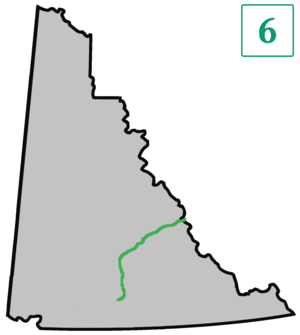

| Yukon Highway 6 | ||||

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by Yukon DOH&PW | ||||

| Length | 279 mi (449 km) | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | ||||

| North end | Canol Heritage Trail at the Northwest Territories border | |||

| Location | ||||

| Country | Canada | |||

| Province | Yukon | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

The Canol Road starts at Johnson's Crossing on the Alaska Highway near the Teslin River bridge, 126 kilometres (78 mi) east of Whitehorse, Yukon, and runs to the Northwest Territories border. The highway joins the Robert Campbell Highway near Ross River, Yukon, where there is a cable ferry across the Pelly River, and an old footbridge, still in use, that once supported the pipeline.

Wartime History

editConstruction and development of the Alaska Highway and airfields along the Northwest Staging Route and provision of military bases in Alaska led to a determination that a source of fuel was required. High-grade oil was available at Norman Wells, and the scheme was to construct a pipeline to Whitehorse.

Assorted components, including pieces from Texas, were moved to Whitehorse to construct a refinery. A road was built to provide access to build and service the pipeline.

At first, the effort was to move all construction activity for the pipeline and road to Norman Wells from northeastern Alberta. This required the use of winter roads and river movement, including several portages around rapids, and was soon found to be cumbersome, slow, and a bottleneck. Ultimately, construction proceeded both from "Canol Camp" (across the Mackenzie River from Norman Wells) and Whitehorse, and the roadway was joined in the vicinity of the Macmillan Pass in the Mackenzie Mountains, on the Yukon–Northwest Territories border, December 31, 1943.

The 4-inch (101.6 mm) pipeline was laid directly on the ground, and the high grade of the oil allowed it to flow even at −80 °F (−62 °C). Workers on the road and pipeline had to endure mosquitoes, black flies, extreme cold and other difficult conditions. One poster for the company that hired workers warned that the conditions could be life-threatening, emphasising that if people were not willing to endure the conditions, they should not apply for the work.

The oil flow commenced in 1944, but was shut down April 1, 1945, having not performed entirely satisfactorily. Some supplementary pipelines were installed to distribute product from the Whitehorse refinery, which also closed in 1945. Twelve tankers-full of oil were delivered to Alaska annually in spite of the perceived threat from Japanese occupation of the Aleutians, while Canol only provided the equivalent of one tanker-full.

Post-War History and Status

editSome of the supplementary pipelines remained active into the 1990s, although the line to Skagway, Alaska, had its flow reversed, and it was used by the White Pass and Yukon Route railway to move petroleum products into the Yukon.

Portions of the primary pipeline between Whitehorse and Canol was later removed and sold for use elsewhere. The refinery was purchased in early 1948 by Imperial Oil, dismantled, and trucked to Alberta for the Leduc oil strike.

The roadway is the surviving legacy of the Canol Project. Although abandoned in 1946–1947, the southernmost 150 miles (240 km) was reopened in 1958 to connect Ross River, Yukon, with the Alaska Highway. A molybdenum mine briefly operated along this part of the route in the late 1950s.

The next 130 miles (210 km) from Ross River to the Northwest Territories border was reopened in 1972, and soon after, mining exploration companies used the route to reach into the N.W.T., including the use of washed-out, bridgeless roadway to scout for minerals, although none beyond the border have been developed. A barite mine has operated near the north end of the Yukon section.

The highway was designated as Yukon Highway 8 until 1978, when it became Yukon Highway 6.

The Yukon section of the road is little changed from 1945, although culverts have replaced some of the original one-lane bridges, and several one-lane Bailey bridges remain. There are very few two-lane bridges on the road. Many are marked with a sign indicating differing vehicle weight limits above and below −35 °C (−31 °F), seemingly redundant since the road is closed in winter, when such temperatures would happen.

It is a winding, hilly road, resembling the original Alaska Highway (which has since been substantially upgraded); the road is not recommended for RVs, and traffic is very light. Occasionally, the road's alignment is emphasized with signs that show the symbol for winding road. There are few guardrails, and other than a government campground, no facilities exist except at Ross River.

Former Yukon Member of Parliament Erik Nielsen owned a cabin for a retreat at Quiet Lake, and at party meetings, some people showed up with signs identifying themselves as delegates for Quiet Lake. Quiet Lake was the location of a small boat used by military officers for recreation during the war; that boat is now at the Transportation Museum in Whitehorse.

Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers wrote and performed a song called "Canol Road" which names several settlements in the area.

Northwest Territories section

editMile Zero of the Canol Road was located at Norman Wells where vehicles drove across the ice in the winter.[1] From the banks of the Mackenzie River (Milepost 4) the road extends 236 miles (380 km) southwest to the Yukon border. The main site of project administration and operations, including a large airfield, was at Camp Canol (Milepost 8).[2]

The Canol Road is not maintained in the Northwest Territories and all bridges are gone. The road remains passable for some distance past the border depending on the capabilities of the vehicle. Vehicles commonly drive as far as the airstrip and buildings located at Milepost 222.

The prospect of the Northwest Territories portion being repaired for automobile use is unlikely. It is an extremely difficult route in sections and the road condition has badly deteriorated. If the demand existed for a road between Ross River and the Sahtu region, it would make more sense to build along an entirely new route that was actually recommended in 1942 by the First Nations member who was called upon to locate a route. Such a route would emerge from the mountains opposite Tulita, Northwest Territories.

The 350 kilometres (220 mi) of Canol Road between Milepost 222 and the Mackenzie River is now the Canol Heritage Trail and traveled by hiking and mountain biking.

Clean up of the Northwest Territories section has been underway since 2007 to remove old telegraph wire, remove hazardous materials and demolish or board up old buildings.[3] When remediation is complete it will allow the creation of a territorial park to proceed as set out in the Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement.[4]

Junctions

edit| Location | km | mi | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnsons Crossing | 0.0 | 0.0 | Hwy 1 (Alaska Highway) – Whitehorse, Watson Lake | Southern terminus | |

| south of Ross River | 220.2 | 136.8 | Hwy 4 (Robert Campbell Highway) – Ross River, Watson Lake | Beginning of concurrency with Highway 4 | |

| west of Ross River | 228.2 | 141.8 | Hwy 4 (Robert Campbell Highway) – Carmacks, Watson Lake | Ending of concurrency with Highway 4 | |

| Northwest Territories border | 471.5 | 293.0 | Canol Heritage Trail | Northern terminus | |

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

In popular culture

editStan Rogers wrote a song referencing Canol Road, with it appearing on his album Northwest Passage.[6] The song details a man who tries to escape the police on Canol Road after all other ways are blocked, and subsequently freezing to death.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Finnie, Richard (1945). CANOL: The sub-Arctic Pipeline and Refinery Project constructed by Bechtel-Price-Callahan for the Corps of Engineers United States Army 1942-44. Taylor & Taylor.

- ^ Finnie, Richard (1945). CANOL: The sub-Arctic Pipeline and Refinery Project constructed by Bechtel-Price-Callahan for the Corps of Engineers United States Army 1942-44. Taylor & Taylor.

- ^ Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, Government of Canada. "Canol Trail Remediation Project". Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "17.3 Canol Trail and Dodo Canyon". Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (Report). Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. 15 September 2010.

- ^ "Canol Road guide". The Milepost. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ https://www.discogs.com/release/3139036-Stan-Rogers-Northwest-Passage#:~:text=B3-,Canol%20Road,-Acoustic%20Guitar%20%E2%80%93 [bare URL]

- ^ "Stan Rogers – Canol Road".

- Gage, S. R. (1990). A Walk on the Canol Road: Exploring the First Major Northern Pipeline. Mosaic Press. ISBN 978-0-88962-438-2. Reprinted in 2012 by the Norman Wells Historical Society (Covers history of the pipeline and description of the backpacking trail.)