This article needs to be updated. (April 2014) |

The California State Board of Equalization (BOE) is a public agency charged with tax administration and fee collection in the state of California in the United States. The authorities of the Board attempt to ensure that counties fairly assess property taxes, collect excises taxes on alcoholic beverages, administer the insurance tax program, and other tax collection related activities.[1]

| |

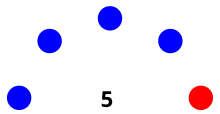

Partisan makeup of the Board of Equalization. | |

| Board overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1879 |

| Type | Tax administration and fee collection |

| Jurisdiction | Government of California |

| Headquarters | Sacramento, California |

| Employees | 400 |

| Board executives |

|

| Website | www |

The BOE is the only publicly elected tax commission in the United States.[2] It is made up of four directly elected members, each representing a district for four-year terms, along with the State Controller, who is elected on a statewide basis, serving as the fifth member. In June 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation stripping the Board of many of its powers, returning the agency to its original core responsibilities (originating in the State Constitution in 1879).

History

editThe State Board of Equalization was created in 1879 by the ratification of the second Constitution of California. Its original mandate was to ensure that property tax assessments were uniform and equal across all counties in the state.[1]

Prior to the creation of the state income tax, sales tax, and fuel taxes in the 1930s, California's state government was almost completely supported by property taxes, which were and still are assessed at the county level by elected tax assessors. Assessors were tempted to boost their popularity with county voters by undervaluing voters' property (and thereby lowering their taxes). This presented the risk of counties with honest assessors paying more than their fair share of the burden of operating the state government, so the Board of Equalization was created to equalize the burden.

The California Franchise Tax Board and the Employment Development Department are separately also responsible for collecting taxes.[3] Some have criticized this as inefficient.[4] Efforts to reform the Board were made in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1990s, and 2000s.[3]

In 1994, Governor Pete Wilson vetoed a plan by the legislature to abolish the Franchise Tax Board and give its responsibilities to the Board of Equalization, explaining in his veto message that the state should have done the opposite. In 2004, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger released a 2,500-page report seeking to merge the Board with other agencies and then promoted a bill by Assemblywoman Lois Wolk to do just that. The effort failed.[3] In 2008, the agency employed approximately 3,950 people throughout the state.[5]

By 2017, the Board had expanded to collecting $60 billion a year. It collected sales and use taxes, hazardous waste fees, jet fuel taxes, marijuana taxes, and over 30 additional taxes. That year, the Board had 4,700 employees and a $617 million annual budget. Board members are paid a $137,000 annual salary and are each allowed to hire a 12-member staff. Each year, the Board spends at least $3 million on education events where elected members appear before their constituents.[3]

In March 2017, an audit by the California Department of Finance revealed missing funds and signs of nepotism, leading to calls for the governor to put the Board under a public trustee.[6][7] In June 2017, the California Department of Justice began a criminal investigation into the members of the Board.[8]

On June 27, 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed into law legislation stripping the Board of many of its powers. The legislation created two new departments controlled by the governor responsible for the Board’s statutory duties, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration and the California Office of Tax Appeals.[9]

The Board still has its constitutional powers to review property tax assessments and insurer tax assessments, and its role in the collection of alcohol excise and pipeline taxes.[10] It retained 400 employees, with the rest of its 4,800 workers being shifted to the new departments.[9]

In 2023, constitutional amendment ACA-11 was introduced by Phil Ting in the California State Assembly to abolish the board and redistribute its staff and duties to other state tax agencies.[11] The Los Angeles Times editorial board called for ACA-11 and ACA-9, which would abolish the elected position of California State Superintendent of Public Instruction, to pass the legislature and appear before voters as a ballot proposition.[12]

Equalization districts

editFor the purposes of tax administration, the BOE divides the state into four Equalization districts, each with its own elected board member.[13] District boundaries are redrawn following the decennial census. The latest boundaries were drawn following the 2010 census and have been in effect since January 1, 2015.[14]

First district

editThe First Equalization District is made up of the following counties: Alpine, Amador, Butte, Calaveras, El Dorado, Fresno, Inyo, Kern, Kings, Lassen, Madera, Mariposa, Merced, Modoc, Mono, Nevada, Placer, Plumas, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Shasta, Sierra, Siskiyou, Stanislaus, Sutter, Tulare, Tuolumne and Yuba; a portion of Los Angeles County including the cities of Azusa, Bradbury, Claremont, Duarte, Irwindale, La Verne, Lancaster, Palmdale, Pomona, San Dimas, San Fernando and Santa Clarita; and most of San Bernardino County, the portion not included in the Third and Fourth districts. From 2003 until 2015 most of this area was the Second District.

Second district

editThe Second Equalization District is made up of the following counties: Alameda, Colusa, Contra Costa, Del Norte, Glenn, Humboldt, Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Monterey, Napa, San Benito, San Francisco, San Luis Obispo, San Mateo, Santa Barbara, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Solano, Sonoma, Tehama, Trinity and Yolo. From 2003 until 2015 most of this area was the First District.

Third district

editThe Third Equalization District is made up of Ventura County; most of Los Angeles County, the portion not included in the First District; and the city of Chino Hills in San Bernardino County. From 2003 until 2015 most of this area was the Fourth District.

Fourth district

editThe Fourth Equalization District is made up of the following counties: Imperial, Orange, Riverside and San Diego; and a portion of San Bernardino County including the cities of Colton, Fontana, Grand Terrace, Highland, Loma Linda, Redlands, Rialto, San Bernardino, Twentynine Palms, Yucaipa and Yucca Valley. From 2003 until 2015 most of this area was the Third District.

Members of the Board of Equalization

editCurrent members

edit-

Ted Gaines (R)

(First District) -

Sally Lieber (D)

(Second District) -

Tony Vazquez (D)

(Third District) -

Mike Schaefer (D)

(Fourth District)

List of members

editPrograms

editAfter being reduced to its constitutional responsibilities in 2017, the Board retained almost none of its tax and fee responsibilities.[15][16][17] The only property taxes it actively administers in its entirety are state-assessed properties and the Private Railroad Car Tax; the Board acts only in an appellate role in collecting the Alcoholic Beverage Tax and Insurance Tax, reviewing appeals of denials of claims for refund.[18]

However, the Board does continue to appraise and audit public utilities, railroad companies and properties owned by counties outside of their own jurisdictions, known as 'state-assessed properties', and hear appeals from its own staff appraisals.

Tax administration programs

edit- State-assessed properties

- Private Railroad Car Tax

Regulatory programs

edit- County-assessed properties

Appellate-only programs

edit- Alcoholic Beverage Tax

- Tax on Insurers

| Former responsibilities (as of 2008) |

Sales and use tax programsedit

Special tax and fee programsedit

Property Tax Programsedit

Tax Appellate Programsedit

|

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b State Board of Equalization, About BOE

- ^ State Board of Equalization, Board Members

- ^ a b c d Ashton, Adam (23 April 2017). "For 90 years, Californians have tried to kill this tax board. This is why they failed". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Daniel L. Simmons, California Tax Collection: Time for Reform, 48 Santa Clara L. Rev. 279 (2008).

- ^ State Board of Equalization, 2007-2008 Annual Report, Profile, "Governance" p. 3.

- ^ Ashton, Adam (24 March 2017). "Audit: California tax collectors on 'parking lot duty' for promotional events as politicos push boundaries". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Ashton, Adam (31 March 2017). "Here's the audit shaking up the Board of Equalization". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Ashton, Adam (20 June 2017). "Criminal investigation targets California tax board leaders". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b McGreevy, Patrick (27 June 2017). "In massive shakeup, Gov. Jerry Brown breaks up California's scandal-plagued tax collection agency". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "California – Bill shifts nearly all tax administration and appeal functions from the BOE to two new tax organizations". PricewaterhouseCoopers. June 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "ACA 11: State tax agency". CalMatters. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ Editorial Board (March 27, 2023). "Editorial: The Board of Equal What? Let California voters decide whether to dump pointless elected positions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Maps: Final Draft Board of Equalization Districts | California Citizens Redistricting Commission". wedrawthelines.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Equalization, California State Board of. "BOE District Boundaries Effective January 5, 2015 - California State Board of Equalization". www.boe.ca.gov.

- ^ State Board of Equalization, 2007-2008 Annual Report, Profile, "Tax and Fee Programs, 2007-2008" pp. 2.

- ^ State Board of Equalization. "Special Taxes". Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- ^ "Summary of Constitutional and Statutory Authorities" (PDF). California State Board of Equalization. December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-09-23.

- ^ "Fact Sheet" (PDF). California Board of Equalization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-25.