C-Squat is a former squat house located at 155 Avenue C (between 9th and 10th Streets) in the Alphabet City neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City that has been home to musicians, artists, and activists, among others. After a fire, it was taken into city ownership in 1978 and squatters moved in 1989. The building was restored in 2002 and since then it has been legally owned by the occupants. Its ground-floor storefront now houses the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space.

| C-Squat | |

|---|---|

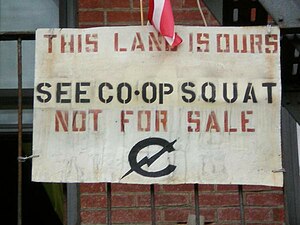

Squatters' notice at C-Squat | |

| |

| General information | |

| Address | 155 Avenue C |

| Town or city | Manhattan, New York |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°43′33″N 73°58′40″W / 40.725708°N 73.977791°W |

| Completed | 1872 |

| Known for | Former squat house |

History

editFounding

editConstructed in 1872, this pre-Old Law Tenement housed a pickle shop, cigar factory, cabinetmaker's workshop,[1] saloon, bookbinder, tailor, and Republican meeting hall.[2] The building was ravaged by a fire and New York City assumed possession in 1978.[3] Some tenants, mainly Latino and black people, stayed on as squatters, running an illegal after-hours club. Six years later, they were evicted. The building then stood empty until 1989 when the current squatters arrived. It has remained occupied.[4]

Journalist and author Robert Neuwirth described the situation that gave birth to many of New York's squats, including C-Squat, in the late 1970s through 1980s, "In the 1970s, scores of landlords walked away from old tenement buildings. Many buildings slid into vacancy and rot. By the 1980s, squatters took over many of the structures in fringe areas such as Alphabet City (Avenues A to D) in the Lower East Side and in certain areas of the Bronx and Brooklyn. They had to fight to stay. The city dispossessed hundreds of squatters, sometimes mounting massive paramilitary attacks on their buildings. In the end, 12 squatter buildings survived, and they outlasted official resistance."[5]

After extensive negotiations beginning under Giuliani's administration, New York City granted provisional ownership of C-Squat and 11 other Lower East Side squats to the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) in 2002. The not-for-profit oversaw the squat's renovation and conversion into resident-owned cooperative housing.[6][7][8] One squat's residents elected not to participate in the UHAB-managed legalization process and are suing for ownership under adverse possession.[9][10]

Working in partnership with the squatters, the National Co-Op Bank (NCB), and the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), UHAB secured loans to help repair the remaining eleven Lower East Side squats, bringing them up to building and fire code, and forming HDFCs – a kind of co-op housing, which transfers ownership to the building's occupants.[7][8][11] Having completed this process, C-Squat is no longer a "squat," but rather a legally occupied building, purchased by the former squatters in a deal brokered with the city council by the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board in 2002 for one dollar.[9][12]

Entertainment

editFor many years, the building had a half-pipe built from reclaimed materials for skaters in the basement[6] and used to regularly host punk rock shows.[3][4][13]

The building has also hosted a number of artists and activists throughout its history,[3] as Neuwirth discovered when he wrote his article, Squatter's Rites for City Limits Magazine, "To climb the steps in C Squat is to walk up a living graffiti artwork. The halls resemble subway cars from a few decades ago. But instead of monikers, these tags are battle cries for revolution, outlaw logos, complaints, and humorous takes on official slogans..."[14]

Restoration

editWhen it was first squatted, the building was falling apart and central joists had to be replaced. These were sourced second-hand and as cheaply as possible. All repairs on the gutted structure were performed by the squatters themselves, transforming the space as they worked on it.[3][6][15] The DIY rehabilitation of the building was no small task, as Neuwirth noted in his article, "At C Squat, the beams were so rotted that the building had sunk almost a foot in the center. The squatters replaced the joists one by one. They got their replacement beams from workers at a nearby gut rehab. The workers saved the old but still usable joists they were removing and passed them on to the squatters."[14]

Under the terms of the homesteading agreement made in 2002, the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board secured a loan through the National Co-Op Bank to help pay for necessary renovations (bringing the building up to city code regulations for legal occupancy), which the squatters performed themselves, as much as possible, to reduce costs.[7] When construction work was complete, the residents assumed ownership of the building as a limited equity housing cooperative.[6]

Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space

editThe Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS) is a living archive of the Lower East Side's squats and gardens, located in the ground-floor storefront of C Squat at 155 Avenue C. It runs neighborhood tours highlighting the efforts of local residents and organizations to clean up vacant lots and fix up abandoned buildings for community use, also promotes scholarship of grassroots urban space activism by researching and archiving efforts to create community spaces. The exhibitions feature materials that document these actions in order to educate people on the political implications of reclaimed space.

East Village community activists began planning the museum in May 2011 and opened it with public tours in October 2012.

The museum's storefront displays materials such as photographs, posters, zines, underground newspapers, comics, banners, and buttons that show how local residents cleaned up vacant lots and buildings in the area and made them organizing spaces for the community. The museum offers three public walking tours that lead participants to the East Village's most legendary community gardens, squats, and sites of social change and explain their complex and often controversial histories. Tour guides are generally longtime activists, squatters, gardeners, academics, and journalists who were directly involved in some aspect of the neighborhood that is relevant to the museum.[16][17]

Shortly after its opening, The New York Times ran an online feature, proclaiming, "MoRUS Squats on Avenue C"[18] – though the museum is not technically affiliated with C-Squat (nor are they squatters there), but rather an independently operated space. As another Times article from the period noted, the process of legalization brought many new questions to the fore for the squatters, including how to strike a balance between the building's collective needs and those of the larger community. "Ultimately, a majority decided that the [museum] project made sense [...] [as] a tenant that promised to reflect the philosophy that was an important part of the building and the East Village itself."[19]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "BLAMING HIS PARTNER; AN OLD GERMAN, MADE DESPONDENT BY BUSINESS REVERSES, HANGS HIMSELF" (PDF). The New York Times. January 27, 1886. p. 8. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Campaign's Windup: The List of Political Meetings Arranged for This Week" (PDF). The New York Times. November 2, 1905. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bickerknocker, W.D. (2014). Homeo-Empathy 9th & C. New York, NY: Bill Cashman. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Create to Destroy! NYC's C-Squat: Homeo-Empathy 9th & C". Maximum Rock n Roll. July 10, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Neuwirth, Robert (2005) Squatter Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World, p. 236. (Routledge Press, New York, NY) ISBN 0-415-93319-6

- ^ a b c d Ferguson, Sarah (August 27, 2002). "Better Homes and Squatters". Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2024. This process was documented in the documentary film, Your House Is Mine [1]. The Village Voice.

- ^ a b c Steinhauer, Jennifer (August 20, 2002). "Once Vilified, Squatters Will Inherit 11 Buildings". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Strausbaugh, John (September 14, 2007). "Paths of Resistance in the East Village". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Ferguson, Sarah (2014). Bickerknocker, W.D. (ed.). The Struggle for Space: 10 Years of Turf battling on the Lower East Side (PDF). New York, NY: Bill Cashman.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Anderson, Lincoln (2008). "Former squats are worth lots, but residents can't cash in" Archived January 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Villager, Volume 78 – Number 31 / December 31, 2008 – January 6, 2009.

- ^ Higgins, Michelle (June 27, 2014). "Bargains With a 'But' – Affordable New York Apartments With a Catch". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Michael (August 21, 2002). "Squatters Get New Name: Residents". New York Times.

- ^ Correal, Annie (June 12, 2015). "Photographs From the History of C-Squat, a Punk Homestead". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Neuwirth, Robert (2002). "Squatters' Rites" Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. City Limits Magazine, September/October 2002.

- ^ Baitcher, Robyn (December 6, 2010). "On Ave. C, 'The Countercultural Squat'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (March 5, 2012). "Sharing a Part of Activist History in the East Village". The New York Times.

- ^ Balaban, Samantha (September 13, 2010). "East Village News, Culture & Life - The Local East Village Blog - NYTimes.com". Eastvillage.thelocal.nytimes.com. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Rajitkul, Remika (December 28, 2012). "MoRUS Squats on Avenue C". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (March 4, 2012). "Sharing a Part of Activist History in the East Village". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

Further reading

edit- Anderson, Lincoln (January 6, 2009). "Former Squats Are Worth Lots, but Residents Can't Cash in". Vol. 78, no. 31. The Villager. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- Barker, Samuel (October 2, 2001). "A Conversation With Stza and Ezra". Rockzone. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- Ferguson, Sarah (2014). Bickerknocker, W. D. (ed.). "The Struggle for Space: 10 Years of Turf battling on the Lower East Side" (PDF). Homeo-Empathy 9th & C. New York, NY: Bill Cashman.

- Hammett, Jerilou; Hammett, Kingsley (2007). The Suburbanization of New York. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-678-4.

- Marx, Eric (September 2003). "Squatters Face Challenges as New Homeowners". amNY. The Real Deal. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- Mele, Christopher (2000). Selling the Lower East Side: Culture, Real Estate, and Resistance in New York City. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3182-4.

- Mitlin, Diana; Satterthwaite, David (2004). Empowering Squatter Citizen: Local Government, Civil Society and Urban Poverty Reduction. Earthscan Publications. ISBN 1-84407-101-4.

- Rainey, Clint (October 8, 2012). "Cooperative Punks". New York. 45 (32): 12. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Neuwirth, Robert (2005). Squatter Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World. Routledge Press, New York, NY. pp. 236–237. ISBN 0-415-93319-6.

- Neuwirth, Robert (September–October 2002). "Squatters' Rites". City Limits Magazine. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- Shaffrey, Ted (October 14, 2002). "N.Y. Squatters Move on to State of Ownership". Seattle Times.

- Starecheski, Amy (2012). "Interviews by Amy Starecheski, 2009–2012" (Audio recordings, images, and transcripts from this series are stored in 176 digital files.). The Squatters' Collective Oral Histories Project OH.068 – via NYU Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archive, New York, NY.

- Steinhauer, Jennifer (August 20, 2002). "Once Vilified, Squatters Will Inherit 11 Buildings". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- Strausbaugh, John (September 14, 2007). "Paths of Resistance in the East Village". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- Wilson, Michael (August 21, 2002). "Squatters Get New Name: Residents". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2024.